Home > Articles > The Tradition > Bobby Hicks Reflects On His Career

Bobby Hicks Reflects On His Career

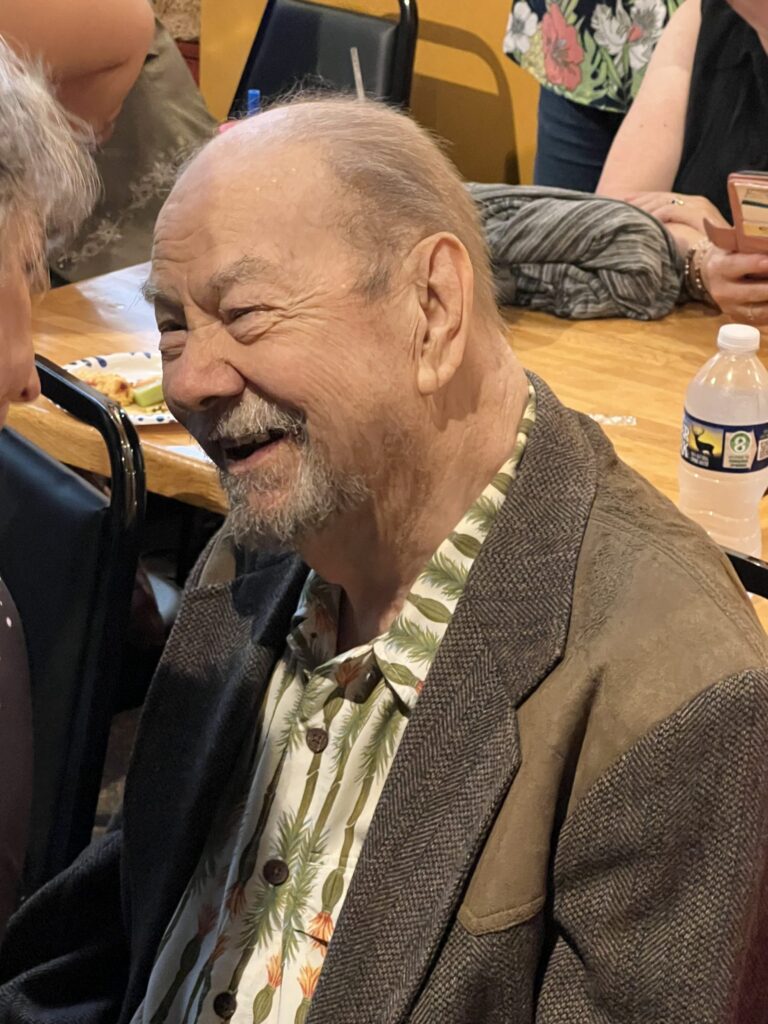

Famed fiddler and king of the double stops, Bobby Hicks, celebrated his 90th birthday in July. Due to problems with his balance and a torn rotator cuff, the fiddle icon can no longer drag the bow, but he has quite the story to tell of his lifetime in the music industry.

Growing up in central North Carolina, Hicks became involved with music at an early age. “My dad bought a ¾ size fiddle that he paid $12.50 for when I was nine years old and I got to messing around with it. I had already played mandolin some so I knew how it was supposed to be tuned. I knew a little bit about it with my left hand, but it’s a whole different thing to play a mandolin and then play a fiddle! A mandolin has frets and the frets are farther apart than the notes are on a fiddle neck. When I got used to that, I played all right. The hardest part was learning how to use the bow.

“I think my dad intended to resell the fiddle, but he told me if I learned to play it that I could keep it. So I did. Nobody in my family played fiddle. My dad didn’t play nothing. My mother played clawhammer banjo some. I never had a (music) teacher of any kind.”

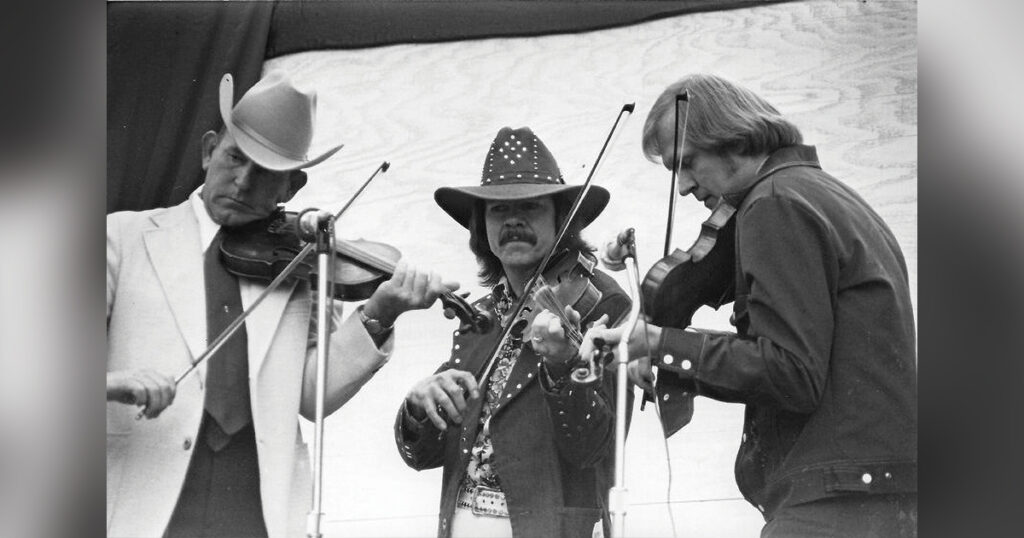

It wasn’t long until Hicks found himself in high demand. “(Promoter and Bluegrass Hall of Fame member) Carlton Haney and my brother used to hang out together when I was growing up, so he knew I played the fiddle. He had Bill Monroe booked for two weeks around the Greensboro (North Carolina) area. Bill didn’t have a bass player, so Carlton came to my house and asked if I’d play bass for him for those two weeks. So I did and he would feature me on the fiddle for one tune every night. I guess he liked what I did because he asked me to go back to Nashville and play fiddle for him.”

Hicks was just 21 when he walked on the stage of the Grand Ole Opry to accompany Bill Monroe. That was the beginning of a lifetime of music, experiences and travel for the North Carolina native that eventually earned him a title.

“When I first moved to Nashville, there was guy who has passed away now named Dale Potter. He was the best I ever heard playing double stops. I learned a lot from him. They used to call him the King of Double Stops. After he passed, they named me that. I play a lot of double stops, but I play them a little different. I play a lead line with moving harmonies. If you move the harmonies just a little bit, it will change the key that you’re playing in. I wrote a few fiddle tunes that I play like that. One is called ‘Angel Waltz’ and another called ‘Zuma’s Swing.’ It came to me while I was having that jam one night.

“Hank Williams, Sr., wrote a tune called ‘They’ll Never Take Her Love From Me’ and I worked it out as an instrumental with the moving harmonies. It made a pretty good little tune. It goes to a little bit different chord pattern. I’ve been playing that way quite a while. That’s why they call me the King of Double Stops. They put me in the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame. I now belong to five halls of fame. I belong to one in Tulsa, Oklahoma, one in North Wilkesboro, North Carolina, one in the Blue Ridge Mountains and another one in Alabama. The one in Alabama was in 2002. They put me and Dale Potter in at the same time which was an honor since I learned so much from him.”

The Professional Musician

Being a professional musician wasn’t always easy; finances varied depending on the popularity of the genre at the time. Hicks was grateful for his time with the Father of Bluegrass, but had to make some hard choices along the way. “Bill Monroe always treated me like his son. He acted like my father when I was working for him. I went to work for him in 1954. I got drafted into the military in 1956. I got out of the military in 1958 and I came back to work for him until 1960. That’s when Elvis Presley was taking over and nobody was making any money (in country and bluegrass music). Bill Monroe was supposed to pay me $90 a week. Back in 1954 that was pretty good money, but he couldn’t work that much because of the rock ’n’ roll thing that was starting. I had to quit and do something else. I went to work for Porter Wagoner for $35 a day. I had just gotten married and had a little girl. It was just as bad with Porter because he only played a couple days a month because he was into big money and didn’t have to work any more than that.

“So I quit Porter, left Nashville, and went to work with a dance band in Iowa. I soon grew tired of that. They were playing schottische which is a lot different than bluegrass. I had a friend who was working in Montana so I went out there and worked for him a while. Then I put my own little four-piece group together: fiddle, guitar, bass and drums. I moved on to Missoula, Montana. I got tired of that so the band and I moved to Las Vegas.”

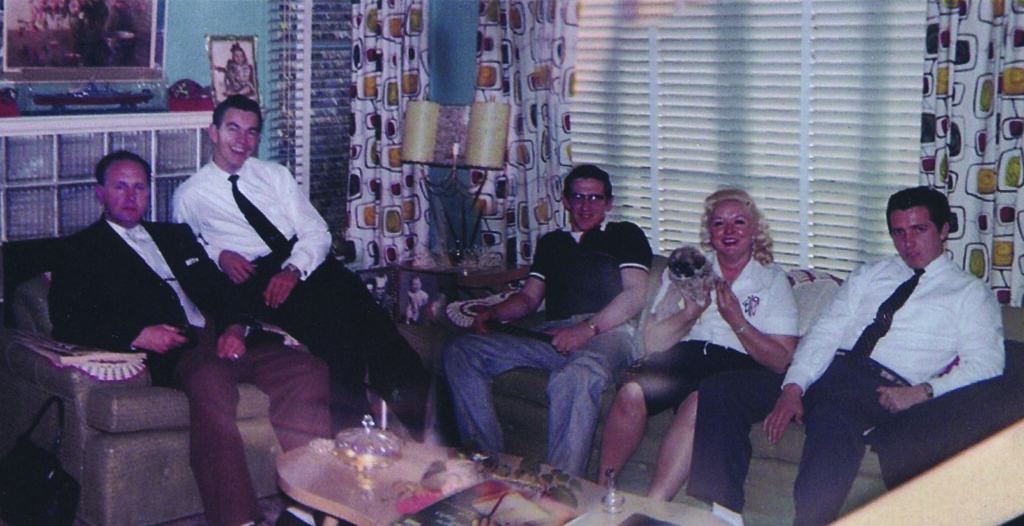

Moving to Vegas was a big gamble for Hicks, but it paid off. “When I drove into Las Vegas, I had an empty gas tank on my car and two dollars in my pocket. That was all the money that I had. I walked into the Golden Nugget looking for a job. I ran into Judy Lynn and I went to work for her. I was told after I took the job that they were actually looking for me, but didn’t know where to find me. I knew them in Nashville before I went out west.

“I went to work for Judy and her husband, a booking agent, in 1963. We played the Golden Nugget six shows a day, six nights a week. That’s 36 shows every week! We also worked Harrah’s Club in Reno and Lake Tahoe. We played three weeks at a time at those three places so I didn’t have to travel a lot. I really liked that.

“Then Judy moved from the Golden Nugget in downtown Las Vegas to playing places along the strip. When that started, she began to travel more. We would drive from Vegas to Florida. We had a big truck. We had a lot of stuff to carry. Everyone had 21 changes of clothes that she had bought for the band. It was full-dress western suits with hats, boots and ties, the same for everyone. It was really a good looking thing when you’d see the band on the stage. I did that until 1970.

“In ’70, I quit her band and moved to Reno, put a little group together there, and worked until 1975. My sister called me and told me that my mother was in the hospital pretty bad off so I dropped everything, gave the band to the boys, and went home to North Carolina. I got home in April and my mother died in August 1975.”

Bobby’s Fiddle

Hicks remained in his hometown of Greensboro, but continued to perform. During this time, he lost a fiddle, but gained a treasure. “I had a fiddle stolen one time in Greensboro. I was playing a dance. I went in the back door where the dressing rooms were. I stuck my fiddle up in the corner where it was dark. Someone must have seen me set it there. When I came back to get it, it was gone. That’s the only time I had one stolen and I never got it back. It wasn’t that much of a fiddle.

“The one I got now a guy, Harvey Keck, in Burlington, North Carolina, built it. He passed away. A lot of people never heard of him, but he built some good fiddles. It’s a five-string and it’s the second five-string he built. The first one he built I didn’t like. I had a four-string in my case that sounded like what I wanted. I took it out and played a little bit for him and said, ‘That’s what I want right there.’ He asked if he could borrow the fiddle. He took it to his shop and somehow built the fiddle I’ve got now called Golden Boy. That’s the name he burned inside of it. He built it in 1976 and I got it in 1977. He wanted $10,000 for it. I told him I couldn’t afford it. He wanted me to take it and play it for a while. From me playing and recording with that fiddle it was so good, he decided to give me that fiddle.” The gift paid off for the luthier. “I sold him $50,000 worth of fiddles playing that one. That was the only two five string fiddles that he ever built. Since then, it’s been the only one that I play. Every fiddle player knows who Golden Boy is. It’s got a tone and a volume that you can stand away from a microphone and it will pick it up like you’re standing right there at it.”

Back to Bluegrass

While living in Greensboro, Hicks came full circle and returned to work for the man that started his musical career. “I started playing festivals for Carlton Haney. Camp Springs was exactly 30 miles from my house. I worked for him. I told him that I didn’t have a group. He paid me $300 to just play with whoever he wanted me to. That’s where I met Ricky Skaggs, J.D. Crowe, Tony Rice and all those guys. They had come on the scene after I had left for Nevada and I had never met any of them. I’d never even heard them play. When I played my first festival for Carlton, J.D. Crowe was there. Ricky Skaggs, Tony Rice and Jerry Douglas were working for him. I played a set with them.”

Hicks must have made quite an impression. “When Skaggs decided to put his country music band together, he asked me to go to Nashville and play fiddle for him, so I did. That was 1981. I worked 22 years for him. It was the longest that I had worked for anyone at the time. I’ve worked ‘vacation’ a little bit longer than that! And I’m really enjoying it very much!”

He performed at some notable venues and for major dignitaries. “I played Carnegie Hall. I played the Lincoln Center. I played a lot of clubs along the strip in Las Vegas. When I was with the Ricky Skaggs Band, we played several times for presidents, both Bushes. I’ve played just about all over the world. I recorded with the Bluegrass Album Band which was Tony Rice, J.D. Crowe, Doyle Lawson, Jerry Douglas and Todd Phillips. Milton Harkey booked us on about a ten-day tour. We played in Greensboro, North Carolina; Roanoke, Virginia; Fort Worth, Texas; and close to Berkley, California. Berkley is where the recording studio was where we did the number one of six albums.

“The first one was supposed to be a bluegrass album for Tony Rice. He decided the tunes. It was so good that he wanted to do another one. We finally wound up doing six of them and calling it the Bluegrass Album Band. I sang bass on some of the gospel stuff they did. Other than that, I just played fiddle.”

Hicks was amazed at the public’s response to the recordings. “Everybody went crazy about that sound. Everybody thought it was a little better than the Flatt & Scruggs thing.”

Marriage and Marshall

Along the way, he met his soul mate, Catherine. “I was doing a fiddle camp in Nashville at the Vanderbilt University and that’s where I actually met her. I didn’t remember her until she came to me in North Carolina to get a fiddle lesson. I asked her what she wanted to play and she said ‘Katy Hill.’ I played it for her and the first thing out of her mouth was, ‘I don’t believe you played that right.’ She was talking about all together a different tune than that, but it was similar. I figured if she’d tell me something like that, she was an honest woman, so I married her.”

They wed in 2003 and the couple settled in the Appalachian Mountains. “I moved to Marshall, North Carolina, which is north of Asheville. My wife was born and raised in Live Oak, Florida. She moved up here to get away from the heat and humidity. She moved up here, bought the property, and built the house that we live in.

“My wife was running a retail store in downtown Asheville. I was there one night in a little jam session. I laid my fiddle down on the counter, walked away, and it fell face down on a cement floor. It fell so straight down that it didn’t break the bridge, but it drove the sound post through the top. I asked, who was the best repair man for instruments? When I found out, it was David Rhodes in Asheville. He passed away now so I have no one to work on my fiddles.

“David took the top off to repair it. He found where Harvey Keck had written on the inside of the back right where the neck connects to it where nobody would ever see that. He wrote: ‘Built to be the greatest instrument in the world in the name of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit.’ So it’s been anointed! That’s why it sounds so good. Amen. I’ve never seen another one that even sounded close to it.

“My wife is a go-getter. I mentioned to her that I would like to play with an orchestra. It was only about a month after that that I was set up to record with the Blue Ridge Orchestra at the University of North Carolina in Asheville. The guy that ran the orchestra had heard me play a time or two and he wanted me to play with them after my wife had asked him. They treated me so well. I played ‘Ashokan Farewell’. I slowed it down and made it a lot better sounding song, I think. When the fiddles in the orchestra took their break, I played harmony to them. That fiddle stood out. It sounded like a lot of fiddles. They couldn’t believe what I was doing. I was playing two parts of harmony to the violin section.”

Hicks got his mountain community involved in his music. “I started a jam session at a place called Zuma’s Coffee House and I did that for 15 years every Thursday night. Then COVID came along and closed us down. For two years, we did nothing. I didn’t go out and play on the road or anything. Now we’ve gone back to doing it once a month on the third Thursday night. That’s all I’ve done for a long time.

Zuma Coffee & Provisions owner, Joel Friedman, interjected, “Bobby Hicks has been instrumental in the development of Marshall through his kindness, his courtesy, and his amazing generosity as a fiddle player. He has continued to share his talent and gift with the whole place. He’s changed the complexity of the neighborhood. He’s been holding a jam here every Thursday for 13 years and once a month the last two years.”

Bobby’s wife, Catherine, readily agreed. “He has made a huge impact on this town. People come from all over the world to the jam. We’ve had folks from Switzerland, Germany and Australia. Folklorist Lowell Jones said, ‘Madison County is where the music never dies.’”

His presence is evident inside the small business. Paintings of Hicks, done by local artist Calvin Edney, Jr., hang on the wall behind the counter and in the front window. All the locals and regulars know him and call him by name. A strong community bond is felt throughout the establishment.

Hicks is content with life at this point. “I traveled with the Grand Ole Opry for 49 years. I’ve been to places that people just dream of. I stood on top of the Eiffel Tower. I’ve been to the Louvre in Paris, France. I spent almost two years in Germany in the military. I don’t know any place I’d rather be than right here. This is the best place I’ve ever seen.”

The fiddler may have laid down his bow, but he embraces his advanced years with grace, dignity, and acceptance. “I’ve got old enough now that I own a Cadillac and a Toyota pick-up truck, but I don’t drive anymore. I don’t trust my driving. I have everything that I need right here. I have fallen several times. So I stay in the house as much as I can. I have been very blessed. If I’d known I’d have lived this long, I’d have taken better care of myself and I mean it!”