Bluegrass Gospel

From Brush Arbor To Bean Blossom And Beyond

Within the expansive genre of bluegrass, gospel music is arguably more popular today than at any time in its history. Most of today’s bluegrass bands include gospel music on recordings and in stage shows, and some record all-bluegrass gospel albums.

While the melding of bluegrass with spiritual music dates to Bill Monroe and his Blue Grass Boys, contemporary artists such as Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver have built careers and reputations on recorded and live performances of bluegrass gospel. While Lawson, who retired from performing at the end of 2021, is known for secular as well as religious songs, the Sullivan Family of Alabama and Georgia’s Lewis Family were among the notable early ensembles performing bluegrass gospel exclusively.

“I think gospel music is kind of a universal music that reaches out to all,” Lawson says. “I don’t think it’s as much style as the message within the song. I grew up around gospel music. My dad sang in an a cappella quartet. They did churches within no more than a 100-mile radius [of home]. I was always around that. And they all read the old shape-note symbols.”

International Bluegrass Music Association Foundation director, Nancy Cardwell Webster, began singing gospel music in church and with her family band in Missouri. “Growing up in a family bluegrass band in the Missouri Ozarks, gospel music was always a big part of our repertoire,” she recalls.

She adds, “I’ve found it interesting that most bluegrass musicians and fans seem to love bluegrass gospel music, whether they understand or believe the lyrics or not…I think folks are drawn to the gospel message of peace that passes understanding, hope for tomorrow, and love for our neighbors as ourselves. There’s a joyful spirit found in bluegrass gospel music that touches hearts and brings a smile.”

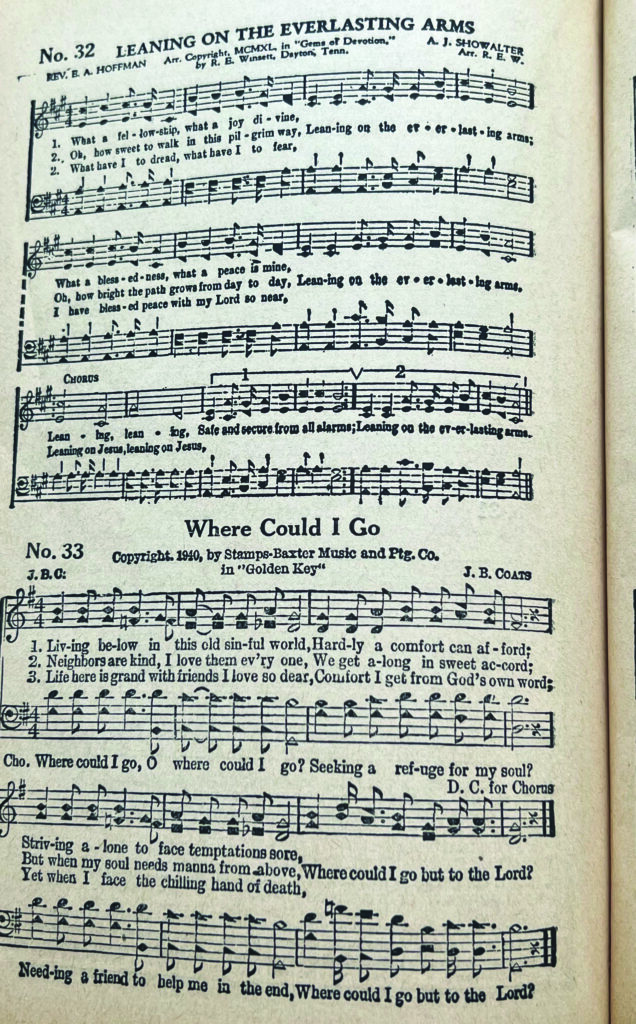

With origins in early 19th Century camp-meetings and brush arbor revivals, the gospel music industry emerged in the decades after the Civil War. Publishing companies, such as Ruebush-Kieffer in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, popularized sacred singing by issuing songbooks using a newly-developed 7-shape system for representing different notes, or tones, for singers. The 7-shape method supplanted the 4-shape notation of the earlier Sacred Harp formulation, expanding the musical possibilities of gospel songs.

In 1875, northerners Ira D. Sankey and Philip P. Bliss published Gospel Hymns and Sacred Tunes, a songbook that embedded lyrics within arrangements inspired by the popular songs of the day. Aimed at bringing young people into the church, the Sankey and Bliss hymns became the principal template for gospel songs well into the 20th Century.

The popularity of the new songs spread quickly, as Ruebush-Kieffer and other publishers hired singing teachers to conduct singing schools throughout the rural South. Armed with songbooks published by their employers and proficient in shape-note technique, singing school teachers moved from community to community, holding singing schools for rural residents during the months before autumn harvests.

The teachers taught songs published in their employers’ songbooks, popularizing the songs and creating a market for the books. In the 20th century, singing schools were an important means by which gospel songs and harmonies entered individual and congregational repertoires. Many shape-note songs, among them “Precious Memories,” “Leaning on the Everlasting Arms,” and “Rank Stranger to Me,” remain popular today.

In 1902, James D. Vaughan, a former singing school teacher from Tennessee, founded the Vaughan Publishing Company. Vaughan promoted his interests by means of singing schools, a monthly magazine (Vaughan’s Family Visitor), and professional quartets that toured the South performing Vaughan’s songs. He added a record company and his own radio station, Lawrenceburg, Tennessee’s WOAN. As more radio stations and record companies opened throughout the region, gospel music became one of the South’s most important expressions of entertainment and faith.

Bill Monroe And Bluegrass Gospel

Long before Bill Monroe assembled his definitive Blue Grass Boys in 1945, gospel music was a significant feature of his life and repertoire. As youngsters, Bill and his siblings were influenced by the singing conventions held in the Baptist and Methodist churches of their hometown, Rosine, Kentucky. These events were sponsored by companies that published gospel songs in the shape note systems developed in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley and elsewhere in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

In a 1991 interview, Monroe told journalist Tommy Goldsmith, “The first singing that I ever tried to do, we’d go to church there in Rosine, Kentucky, at the Methodist or Baptist or then there was a holiness church moved in later on. They sang some fine songs there in Rosine. That played a part in the kind of a sound and the kind of feeling that I wanted to put in my music. Taken right from the gospel sound.”

Between 1936 and 1938, Bill and his brother Charlie worked as the Monroe Brothers on Charlotte, North Carolina’s radio station WBT. There, they made their first records on RCA’s Bluebird label. Their first recording was “What Would You Give in Exchange (For Your Soul)?” According to Monroe biographer Richard D. Smith, this older gospel song “had been a favorite showcase for singing school choirs back in Kentucky.” The Monroe Brothers’ embrace of gospel music is evidenced by the fact that half the 60 sides Bill and Charlie recorded for Bluebird were gospel songs.

When the Monroe Brothers ended their collaboration in 1938, each set out to establish his distinctive style and career. Bill continued exploring and refining his sound until the “classic” Blue Grass Boys lineup with Monroe, Chubby Wise, Lester Flatt, Earl Scruggs, and Howard Watts came together in 1945. In September 1946, the band’s first session for Columbia Records took place in Chicago. The eight recorded tracks featured two original gospel songs: “Mansions for Me” and “Mother’s Only Sleeping.” Though not perhaps “standard” gospel, “Mother’s Only Sleeping” invokes Christian theology as Mother is “patiently waiting for Jesus to come.”

Monroe wrote 19 of the 22 gospel songs the Blue Grass Boys recorded between 1946 and 1952. Thus, just as he had defined bluegrass in its secular form, Monroe emphasized sacred music with the Blue Grass Quartet and by writing songs the Quartet performed.

Monroe brought to his music a repertory of secular and sacred songs he had accumulated since childhood, and eclectic musical tastes that included White and Black elements of style. From the beginning he incorporated into bluegrass elements from Black music such as the blues, and he performed and recorded popular Black spirituals such as “Swing Low Sweet Chariot” and “When the Saints Go Marching In.”

Perhaps the most explicit example of Monroe’s borrowing from Black gospel is the song “Walking in Jerusalem Just Like John,” recorded by the Blue Grass Boys in 1952. In a 1968 interview, Monroe told Alice (Gerrard) Foster and Ralph Rinzler he learned the song from an African-American family he visited in Norwood, North Carolina. “I went by these people’s house and I talked to this man; I believe that maybe he was a preacher…He wanted me to record it and sing it on the Grand Ole Opry. They sang it for me there, kind of like the way I sing it.”

Monroe’s church-song training was shared by other first-generation bluegrass artists. Shape-note hymnals published by the Teacher’s Music Company provided a source of religious songs for Earl Scruggs, while Lester Flatt learned to sing in church near his home in Sparta, Tennessee. Ralph and Carter Stanley sang unaccompanied (a cappella) shape-note hymns in their Primitive Baptist church at McClure, Virginia. The Louvin Brothers’ harmonies derived from shape-note hymnals in the Sand Mountain region of northeast Alabama. While the Louvins are not considered bluegrass, their songs have been covered by many bluegrass artists, including Jim and Jesse, Ricky Skaggs, and Emmylou Harris.

Religious songs were incorporated into the repertoires of most early bluegrass artists. According to bluegrass historian Neil Rosenberg, “Religious songs constituted, on the average, 30 percent of the recorded and published (in songbooks) output of the most influential early bluegrass bands – Monroe, Flatt and Scruggs, the Stanley Brothers, and Reno and Smiley.”

The 52 spiritual numbers Flatt and Scruggs recorded on Columbia Records between 1950 and 1969 stand as some of the most enduring gospel songs in the bluegrass canon. They include such standards as “I’m Working on a Road,” “Get in Line Brother,” “Father’s Table Grace,” “Bubbling in My Soul,” “Joy Bells,” “Gone Home,” and “Who Will Sing for Me?”

In the 1950s musicians and fans began referring to Monroe’s music as “bluegrass,” a nod to the name Monroe had chosen for his band – Bill Monroe and His Blue Grass Boys. The term “bluegrass gospel” came later. Doyle Lawson believes the genre was coined following the popularity of 1981’s Rock My Soul, his second album with Quicksilver. “After Rock My Soul we had a category [Bluegrass Gospel] for the Dove Awards and the Grammys. Everybody was scrambling to have a quartet. You have new groups now whose intentions are to play nothing but bluegrass gospel.”

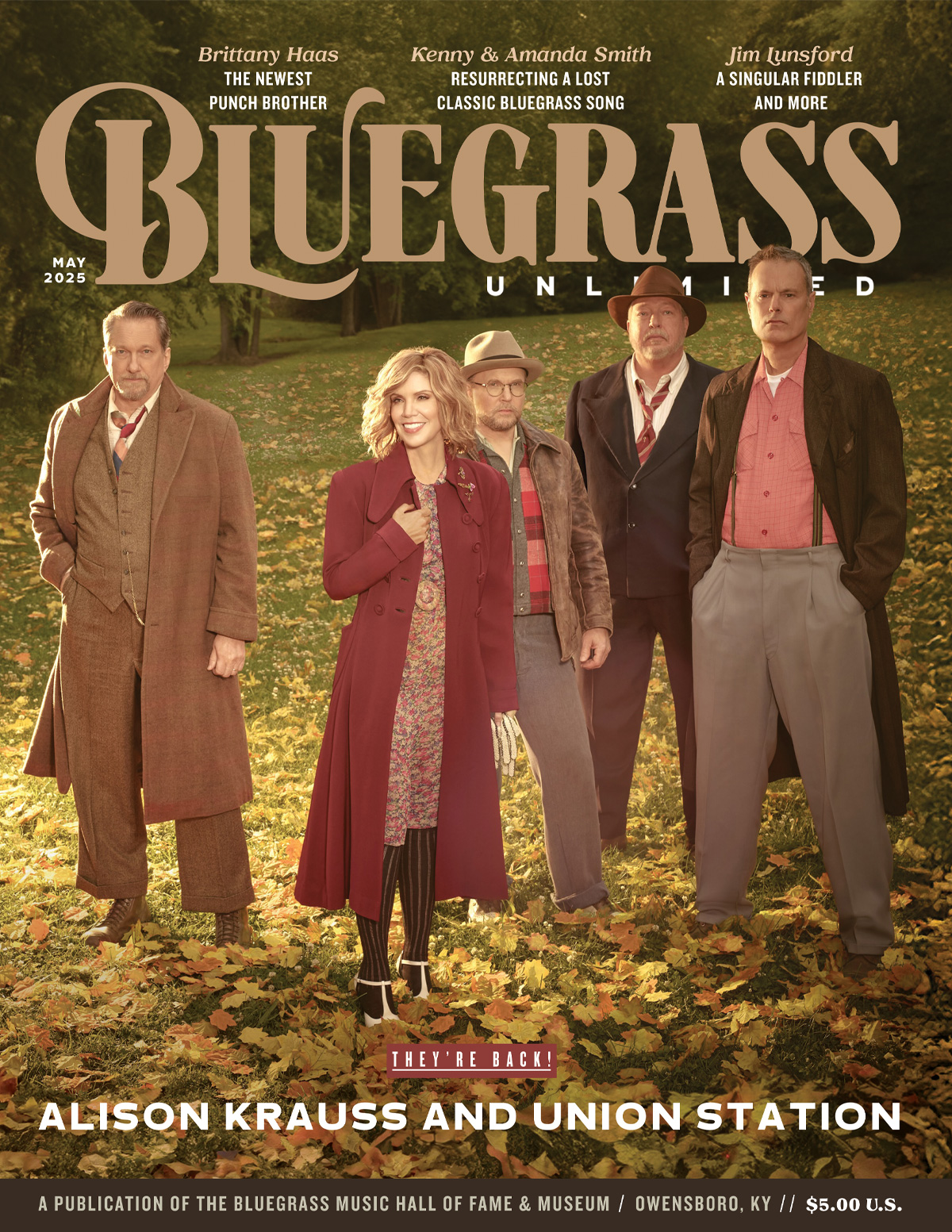

One of the first bluegrass groups to play gospel music exclusively was the Sullivan Family of St. Stephens, Alabama. Featuring Enoch Sullivan on fiddle, his wife, Margie, on guitar and lead vocals, and other family members through the years, the Sullivans were led by Enoch’s father, Arthur Sullivan.

Brother Arthur was a Pentecostal preacher who carried his family with him to revivals and camp meetings in the 1940s and ‘50s. The Sullivan Family turned professional in 1949, making its first broadcast on WRJW radio in Picayune, Mississippi.

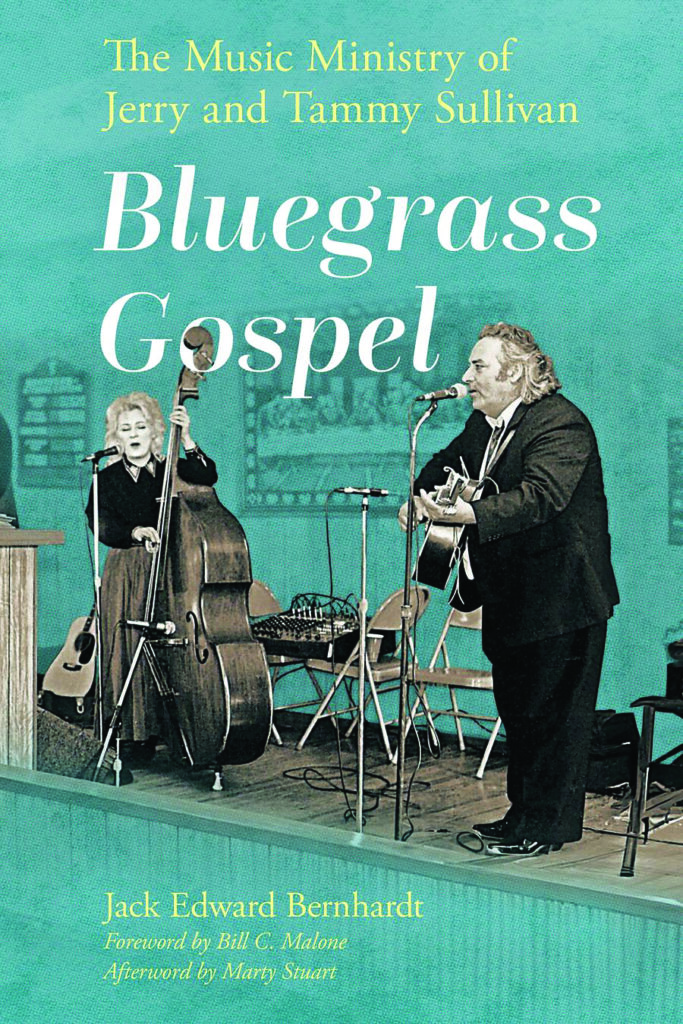

In 1979, Jerry and Tammy Sullivan (Arthur’s brother and Jerry’s daughter) launched their own bluegrass gospel ministry which endured until Jerry’s death in 2014.

Billed as “The First Family of Bluegrass Gospel,” the Lewis Family chose an all-gospel career in 1951, two years after the Sullivan Family began their professional career as a gospel music ministry.

In The Sullivan Family: Fifty Years in Bluegrass Gospel, the authors assert that Bill Monroe suggested in 1968 or ’69 that the Sullivans call their music “bluegrass gospel.” The Sullivans were playing festivals with Monroe at the time, so they likely used the term for marketing shows featuring Monroe and the Sullivans on the same bill.

The origin of the term “bluegrass gospel” is open to debate. It’s also less significant than the actual merging of sacred music with bluegrass, and its increasing popularity with bluegrass artists and their fans. Bluegrass scholar Fred Bartenstein points out that Carl Story released the album, Bluegrass Gospel Singing Convention, in 1973, and Bluegrass Gospel Collection in 1976. He also points to Story’s 1999 King Records anthology, Father of Bluegrass Gospel.

“I would never dispute that Mr. Monroe did refer to the Sullivans as ‘bluegrass gospel,’” Doyle Lawson allows. “I don’t think the term, or genre, of ‘bluegrass gospel’ really came into prominence until Rock My Soul. That’s when I started hearing it.”

Bluegrass Gospel As A Source Of Solace, Hope, And Joy

From modest beginnings in shape-note hymnals and brush arbor revivals, through its incorporation into bluegrass by Bill Monroe and others, gospel music remains grounded in Southern folk tradition. It draws upon a common Protestant heritage expressed through shared cultural symbols of faith and songs extolling the message of forgiveness, redemption, and the promise of eternal salvation.

In the midst of today’s complex and rapidly changing cultural landscape, it’s not surprising that bluegrass gospel is celebrated and enjoyed by bluegrass artists and fans. Lawson views bluegrass gospel as a way for people to cope with the rapid, often confusing pace of today’s societal change. “I think people are looking for something to hold on to in a spiritual way that’s not seen but felt. We live in a turbulent world. I believe there is a better place, and that’s what I like to sing about. I think people are looking for something they can hold in their hearts. When they listen to gospel music they find comfort.”

Bluegrass artist and advocate Nancy Cardwell Webster agrees that bluegrass gospel offers both joy and sanctuary to fans seeking solace in today’s tumultuous world.

“I’m glad bluegrass gospel music is still popular today,” she says. “It’s an integral part of the history of bluegrass music, it’s fun to sing and play, and there’s just something so encouraging and hopeful about it for seekers as well as believers.”

The author thanks Doyle Lawson, Nancy Cardwell Webster, and Fred Bartenstein for contributing to this article.

Jack Bernhardt’s book, Bluegrass Gospel: The Music Ministry of Jerry and Tammy Sullivan, scheduled for publication in July, is available for pre-order at www.upress.state.ms.us/Books/B/Bluegrass-Gospel