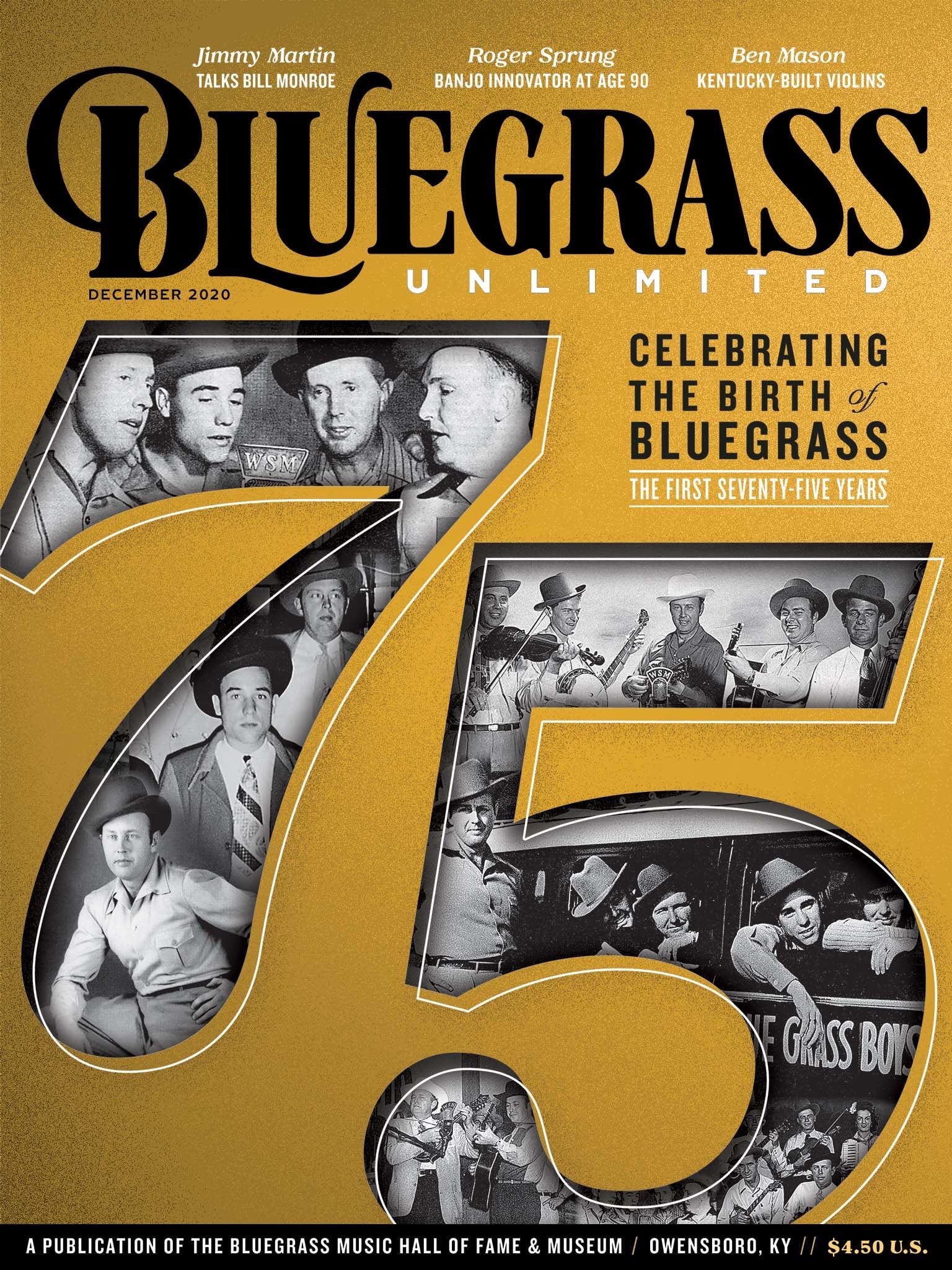

Home > Articles > The Tradition > Bluegrass Funnyman

Bluegrass Funnyman

In the formative days of bluegrass, bands sought to offer a well-rounded entertainment package. Music, naturally, was the core of the programs but comedy was always an important component. Ralph Stanley, in speaking of the early days of the Stanley Brothers, recalled that “we used a comedian all the time; somebody would dress up and we had a name for him, like Cousin Winesap.” The practice was a holdover from vaudeville days and traveling minstrels. “Before we ever started,” Ralph said, “they had these medicine-shows — they would make up this medicine and sell it, and have some kind of entertainment to draw the crowd out.” Times changed and fans tastes became more sophisticated. By the middle 1970s, Ralph observed that “they come out mostly to see and hear.”

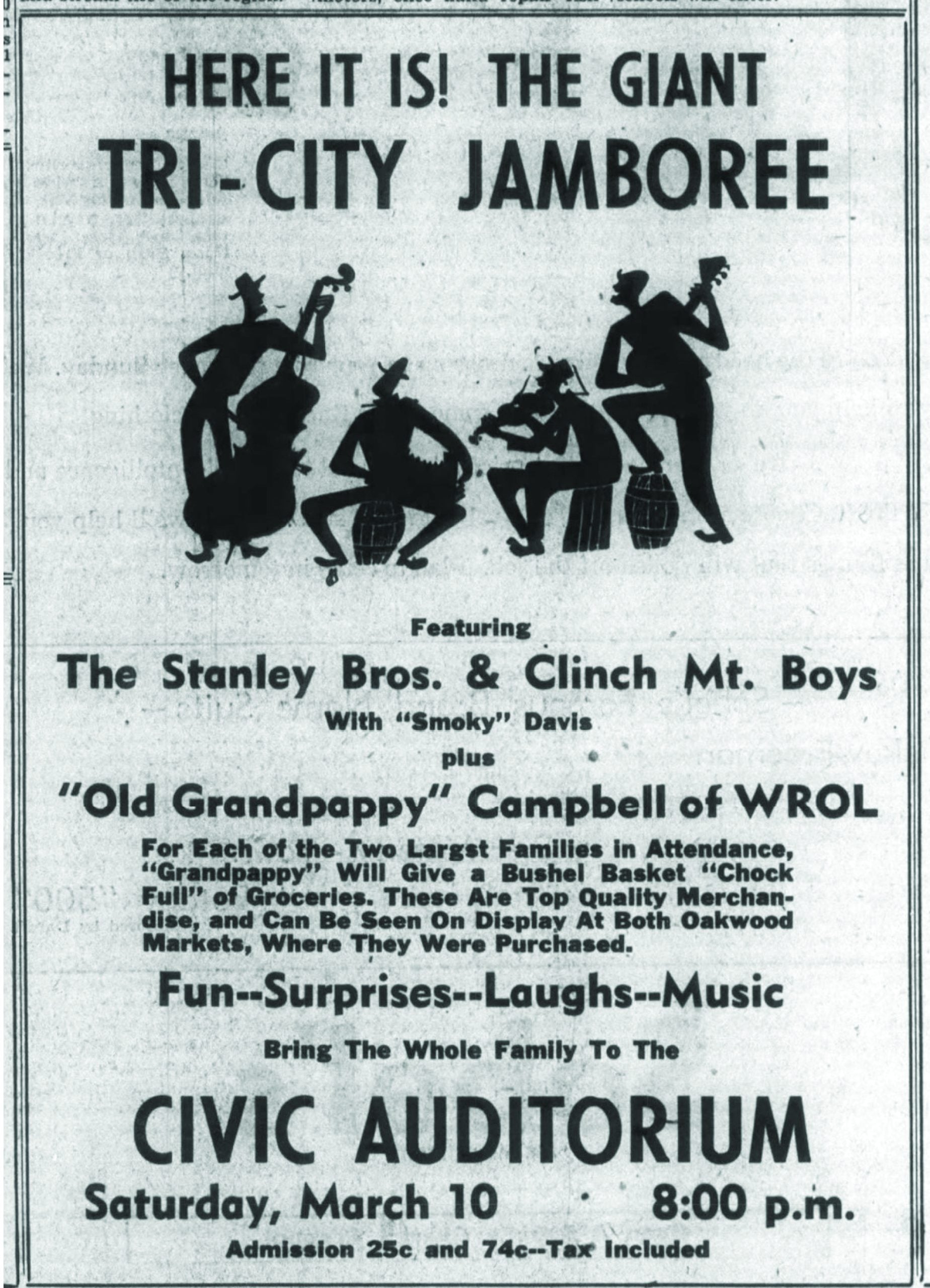

A comedian who livened up many a bluegrass show was Charles F. Davis. But nobody knew him by his given name. Since the middle 1920s, he’d always been known as Smokey. Smokey Davis. He shared the stage with a number of first-generation bluegrass groups, including Mac Wiseman, the Stanley Brothers, the Sauceman Brothers, Ralph Mayo’s Southern Mountain Boys, Jim and Jesse McReynolds, and, reportedly, Flatt and Scruggs.

Smokey Davis was a native of Bristol, Virginia. He was born there on May 23, 1906, the fifth of six children, to Charles and Laura Ellen Grant Davis. Not much is known of Smokey’s childhood, save for the fact that his younger brother, James Reece Davis, died in 1912 at the age of one and a half. A decade later, in October 1922, Smokey appeared in a theatrical production that was sponsored by the local American Legion post. The Jollies of 1922 was touted to be the “greatest show event of its kind ever staged in Bristol,” despite the fact that it “was a flop” on Broadway. The show was a mix of minstrelsy, musical comedy, and vaudeville and no doubt foreshadowed Smokey’s entry into the world of entertainment.

Although comedy was to be his forte, Smokey was known early on to be somewhat musical. Fries, Virginia, fiddler Glenn Neaves recalled seeing Smokey at a music contest in the early or middle 1920s and the comedian played guitar. Also in attendance was fiddler G. B. Grayson.

Smokey was a frequent attendee at fiddle contests. A photo from the famous 1925 convention in Mountain City, Tennessee, showed him in the middle of the back row. Around him was a cast of now legendary old-time musicians including Fiddlin’ John Carson, Charlie Bowman, Al Hopkins, Fiddlin’ Powers and family, Tom Ashley, and G. B. Grayson; the last of which Davis played with locally.

Although he’d probably been working the act prior to this, an advertisement for a June 1927 fiddlers contest in Abingdon, Virginia, announced that part of the event’s entertainment would be “SMOKY DAVIS and his Black Face Comedians.” It was this manner of performance that Davis specialized in during the 1920s and ‘30s. While some of those who have donned blackface in more recent times – including governors and prime ministers – have been summarily chastised, the practice was still a part of popular culture in early part of the twentieth century. It was at a 1927 concert / contest / fundraiser — attended by Tennessee Governor Alf Taylor — that the “blackface comedy and singing and dancing of ‘Smokey’ Davis, of Bristol, who appeared in costume, swayed the audience with his wit and action.”

One group of musicians that Smokey plied his trade with was the Tenneva Ramblers, a group from the Bristol, Virginia/Tennessee, area whose claim to fame is that they almost — but didn’t — record with Jimmie Rodgers at the famed Bristol sessions of 1927. The core of the group was comprised of brothers Jack and Claude Grant. They were Bristol residents who were first cousins to Smokey. Their father, Sam W. Grant, was the brother of Smokey’s mother. Claude recalled that “Smokey Davis was a big, long, tall guy, and his appearance would make people laugh.”

The Tenneva Ramblers and Smokey met Rodgers at a Rotary Club convention in Johnson City, Tennessee, in April 1927. The Ramblers were hired to provide entertainment. Claude remembered that “of course we took Smokey Davis with us, for blackface comedy. The event was in the daytime, so naturally we did not do any blackface acts or skits, just jokes. We’d play awhile, and then Smokey would come out and he’d do a few jokes, and we’d play some more and sing.” At the convention, Rodgers struck up a conversation with the Ramblers and they all agreed to collaborate on some show dates. At some point they entertained the notion of recording together at the upcoming Bristol recording sessions that were slated for July and August 1927. But, by the time of the sessions, Rodgers and the Ramblers parted ways.

Although the Ramblers missed their shot at recording with the Father of Country Music, they did go on to make a number of records on their own, including several at a session in Bristol. Later, an article in the February 16,1928, edition of the Bristol Herald-Courier reported that “The Tenneva Ramblers, local musical organization, will leave for Atlanta, Ga., today where they will make several records for the Victor Phonograph Company on Saturday.” The composition of the group included “‘Smokey’ Davis, a comedian, who will stage several original acts. While in Atlanta, the group expects to broadcast several programs.”

Not long after the session for Victor, the Tenneva Ramblers and Smokey were slated to offer entertainment at a fiddlers convention in Blowing Rock, North Carolina. An article for the event noted that “Smoky Davis is known all over the country as a vaudeville comedian who keeps the audience rocking with laughter, while the Ramblers fill the house with music.”

In the early 1930s, Smokey teamed up with the Roe Brothers, a group of “well known entertainers who have toured the United States with such outstanding organizations as the ‘Blue Ridge Ramblers,’ ‘The Original Hill-Billies, [and] ‘Oklahoma Cowboys’… The artists sing and play old time mountain songs as well as popular melodies. ‘Smoky’ Davis and Buddy Hughes, comedy and novelty artists, accompany the troupe.” Perhaps as a sign of changing times, the word “blackface” was omitted from publicity for the show.

On February 22,1935, Smokey was married to Frances Lee Williams. In the 1936, the couple welcomed their only child, a daughter named Bobbie Jean. Frances had a son, Herman, from a previous marriage who came to live in the Davis household. The 1940 census revealed that Smokey’s mother lived there as well.

Smokey made his way to Wheeling, West Virginia (ca. 1937), where he was part of an act with Henry Godwin, aka Hiram Hayseed. Doc Williams, a popular performer from the WWVA Jamboree in Wheeling, noted that “Smoky and Henry did blackface. They were a comedy team when I came here [1937], Hiram knew all these things [routines].” Smokey toured with Doc Williams several years later, in 1942. Williams held Smokey in high regard, noting that “he was funny as all get-out.”

The stint with Williams last for a year or so and by the middle of 1943 Smokey was back in East Tennessee. He appeared at Kingsport’s Labor Day Carnival that was sponsored by the State Guard. Entertainment included the Jimmy Keegan Variety Show. It touted “45 minutes of fun” with a cast of 12 people “and Smokey Davis and Zeb Whetsel.”

Medicine shows were also part of Smokey’s mix. The artform came into being in the 1850s and survived into the 1940s. The programs were comprised of traveling entertainers who plied their trade – a mix of music and homespun humor – for free; they made their money by selling patent medicines. The homemade concoctions were mainly laxatives – with liberal amounts of alcohol thrown in – that were guaranteed to “purge the body” of whatever ailed you. Daughter Bobbie Jean recalled that “we traveled with him some. We were on a medicine show when I was very little and they’d drag me on stage and I’d do something… whatever. I remember my mother telling me that there was a man there that wanted to know what my dad looked like. I said, ‘I don’t know. In the day time he’s white like me and at night he’s black like you.’ So, I was a little confused.”

Throughout the rest of the 1940s, carnivals provided outlets for Smokey’s talents. Kingsport’s American Legion Independence Day carnivals for 1945, 1946, and 1947 all featured Smokey in one way or another. The 1945 carnival found him paired with comedian Paul Summer. In 1946, with the end of World War II being a very recent memory, the “biggest Fourth in this section in years” paired Smokey with John D. Parker where they served as masters of ceremonies. The 1947 event advertised the duo of Smokey Davis and Paul Summers and pegged Smokey as “one of the South’s outstanding comedians.” Other civic organizations also made use of Smokey’s talents. On August 1,1947, the American Legion Carnival in Elizabethton, Tennessee, booked the duo of Smokey Davis and Paul Summers. In Bristol, Virginia, on February 2, 1948, the local VFW chapter sponsored the Barnyard Follies of 1948. Headlining the show was the Howington Brothers with the Happy Mountaineers, along with Smokey Davis who was billed as the “Clown Price of Comedy.”

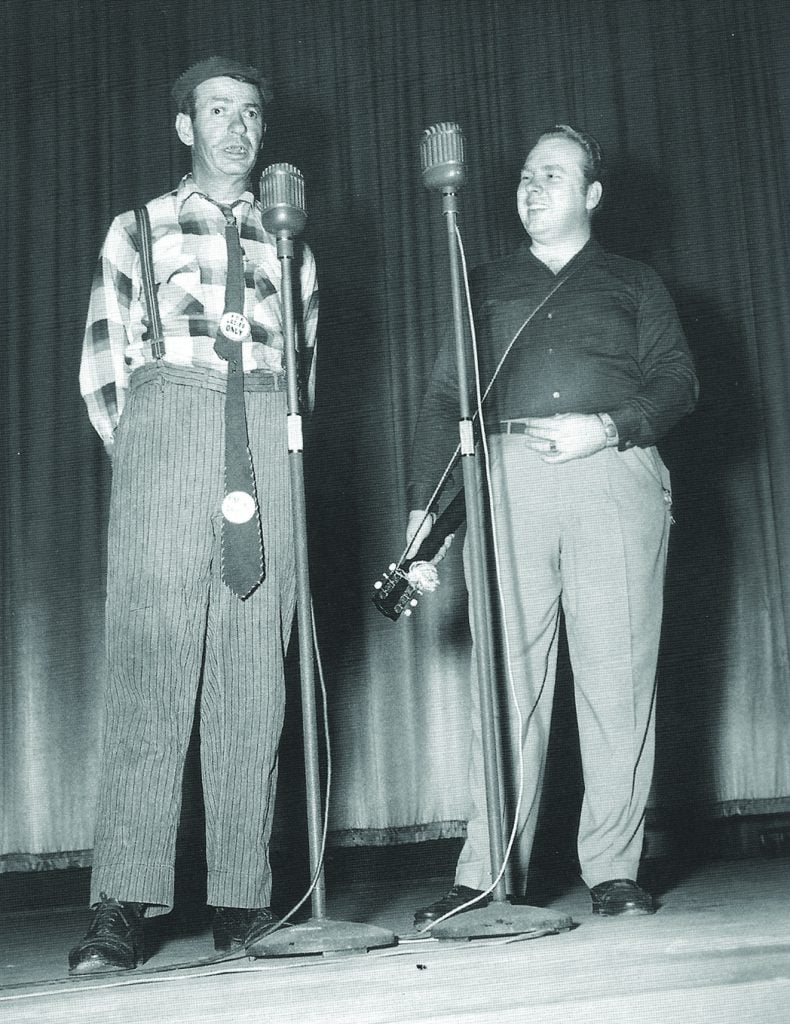

The first documented instance of Smokey’s involvement with bluegrass – then known as hillbilly music – came in the early part of 1948. The Stanley Brothers were in the process of changing fiddlers. Their fiddler of the last year and a half, Leslie Keith, was a fine old-time fiddler but the Stanleys wanted someone with more drive to their playing. Carter and Ralph reached out to North Carolina fiddler Jim Shumate, a veteran of Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys and a recent retiree from Flatt and Scruggs’ Foggy Mountain Boys. Shumate wasn’t interested in a full-time job with the Stanleys, but he had a week of vacation coming to him from the furniture factory where he worked. He used the week – which was in late February or early March 1948 – to fill in with the Stanley Brothers until they could find a full-time replacement. During his week with the Stanleys, Shumate noted that “they had a comedian… big tall fellow… Smokey Davis. He would always sit and tell jokes when we’d get in the car… [he’d] just keep us all laughing all the time.”

Carter Stanley observed that “Smokey was a clown at heart but he was a great showman, good comic, and a fellow that had a lot of experience. He’d worked in the business for years and I feel like that people, youngsters new in the business, I feel like they can benefit from the advice of people like that.” Carter often acted as the straight man in Smokey’s comedy routines with the Stanley Brothers.

By May 1948, the Stanleys had a regular fiddler in place. Art Wooten. Like Shumate, he, too, was a veteran of Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys. Throughout May, the group had at least three show dates that included Smokey as part of the bill. The first was on the sixth at the Zephyr Theatre in Abingdon, Virginia. The group also included mandolin player Pee Wee Lambert. On the thirteenth and fourteenth, they played back-to-back shows at the Big Stone Theatre in Big Stone Gap, Virginia, and at the Bolling Theatre in Norton, Virginia.

With the bluegrass acts, Smokey’s comedy was, according to his daughter, “mostly… I think they called it rube. That’s what he did with the rest of the people. He sang, and he also whistled. I’d go down to the radio station and he would sing ‘I’m Looking Over a Four-Leaf Clover’ and everybody around Bristol thought that he made that famous. Of course, it had been famous many years before him. I don’t know if you’re familiar with Al Jolson but he’d do these fancy bird whistles and Smokey could do that, too.”

No doubt some of Smokey’s routines, especially the earlier ones, came from popular entertainers such as Al Jolson, who was dubbed the “king of blackface.” On a more personal level, Smokey was friends and/or acquaintances with comedians such as Rod Brasfield, a mainstay for many years on the Grand Ole Opry, and Max Terhune, a vaudeville performer who later starred in 70 western/cowboy films from 1936 to 1956. Unlike some, who performed their comedy from a script, Smokey was totally “off book.” His daughter noted that “he was funny all the time.”

During part of 1948, the duo of Jim & Jesse, known then as the McReynolds Brothers, worked on radio station WFHG in Bristol. Jesse noted recently, “I think that’s where Smokey come in, we met him around Bristol there. He was always on standby if anybody needed a comedian. He was the best comedian we had around Bristol when we were starting out. ‘Course he worked with a lot of people. He worked with the Stanley Brothers and gosh a lot of other folks that played around there. And he worked quite a bit with us back when we were between bands.

“When we went to Augusta, Georgia [ca. December 1948/January 1949] to work with Hoke Jenkins and Curly Seckler, we got Smokey to come down there and do comedy. We had some experiences with Smokey!” One such experience involved a traveling mishap that, at the time, probably wasn’t all that funny. Again, from Jesse: “We used to ride to the show dates in this automobile that Hoke had and he wanted to check the mileage on it one time. We were going on to our show and we run out of gas in the middle of nowhere. Smokey was with us then and he said ‘Well lookee there, this thing’s getting 30 miles to the gallon.’ By running out of gas he found out what kind of gas mileage he could get on that car. Smokey was kidding him about that all the time.”

Jesse recalled one of the comedy routines that involved Smokey. “He would work with different members of the band. He worked with Curly Seckler together that way when we first went to Georgia. Curly had this routine where he would sit down on stage and start writing some songs. So, I would go out and start bugging him. He was trying to be quiet and write some songs there. Curly had this line when he wanted Smokey to come out with his paddle and get rid of me. He’d say ‘Over the river, Charlie.’ Smokey had this big paddle that had split so when he hit me with it, it would go off like a gun. I put a couple of songbooks in the seat of my britches and was bent over bugging Curly. He started hollering ‘Over the river, Charlie’ and Smokey came out with this big paddle and started hitting me in the seat of the britches. He hit me so hard a couple of times that he almost knocked the books out of the seat of my britches. But we had some routines like that that we did. Basically, he would just go out and do his normal routine.

“Back then, comedy was a big part of it. Even Bill Monroe. Whoever played bass would be the one to do the comedy. I always admired Smokey and learned a lot from him as far as doing comedy. I used to write down all the jokes that he would tell. I had a book at one time I’d carry around. It was just a little hand book to carry in my pocket and look at when I needed to pick out comedy routines. After I worked with Smokey some, I started trying to do comedy myself. I always tried to make my comedy routines out of Smokey’s routines.”

During the summer of 1950, Smokey had a group of his own that was billed as the Smokey Davis Hill- Billies. They appeared at the East Tennessee District Fair in Kingsport along with vaudeville acts and a minstrel show. But by year’s end, Smokey aligned himself once again with a musical act: Curly King and the Tennessee Hilltoppers. King’s group was a regular feature on WCYB’s Farm and Fun Time program. The radio station had its studios in the Shelby Hotel, on the Virginia side of Bristol. A block away was State Street, the dividing line between Virginia and Tennessee. The Paramount Theatre was situated on the Tennessee side of State Street, and it was here that Davis appeared with the Curly King outfit for a November 25, 1950, engagement.

The year 1951 was a busy one for Smokey. He teamed up with some of the best names in what would come to be known as bluegrass and he expanded his performance area well-beyond East Tennessee.

The start of the year found him once again with the Stanley Brothers. The group, with fiddler Lester Woodie and mandolin player Pee Wee Lambert, appeared in person at the Fox Theatre in Kingsport, Tennessee on February 21, 1951. Smokey was advertised on the bill as well. Lester Woodie remembered Smokey as a “great comedian.” He continued, “[He] didn’t play anything but he traveled with us a lot and did a lot of comedy. He and I did a lot of comedy together.”

By the middle of June 1951, the Stanley Brothers decided to take some time off from the road and Carter Stanley went to work for Bill Monroe, later acknowledged as the Father of Bluegrass. Smokey hooked up with Mac Wiseman who was then performing on the Louisiana Hayride in Shreveport. Throughout June and July 1951, Smokey made regular appearances on the Hayride and even participated in a Hayride tour that landed the group at a theatre in Hillsville, Virginia, a scant hour and a half drive from Bristol. The tour was headed by Texas Tyler and included “Okie Jones – Columbia Recording Artist, Martha Lawson — Texas Yodler Beauty, Mac Wiseman — Dot Recording Star, Jimmie Lee — Capitol Record Star, and Smokey Davis — Funnyman.” Three shows were slated for the evening, starting at

6:30 p.m. Admission was 40 cents and 80 cents.

Mac Wiseman — and presumably Smokey, too — left Shreveport in August 1951. On September 5 thru 8, Smokey was a featured part of the Washington County (Tennessee) Fair. The headliners were the local comedy/variety act of Frank and Mack; others featured on the program included the husband/wife duo of Salty Holmes and Mattie O’Neil, Farm and Fun Time entertainers the Sauceman Brothers, the Tennessee Hayloft Gang, and the Burleson Sisters.

Much of Smokey’s work for the next six months took place at the Tennessee Theatre in Johnson City. The theatre hosted a Friday jamboree billed as the Smoky Mountain Hayride. It was broadcast coast-to-coast on the Liberty Network. By the spring of 1952, the program morphed into the Happy Hayloft, which promised “fun – music – and a good time for all,” and eventually settled as the Tennessee Hillbilly Hayride.

The Hayride was a weekly, Friday night event at the Tennessee Theatre that was hosted by Jerry Donovan, a popular announcer from WCYB’s Farm and Fun Time program. Eventually, the Hayride became a showcase for artists from that radio show, including Bonnie Lou and Buster as well as the McReynolds Brothers (Jim and Jesse). Smokey received billing as the “South’s Funniest Comedian.”

The fall of 1953 found Smokey once again with the Stanley Brothers. The band included Carter and Ralph Stanley, bass player John Shuffler (brother of George Shuffler), and mandolin player Jim Williams. The foursome, plus Smokey, journeyed to Bean Blossom, Indiana, for a September 13,1953, appearance at Bill Monroe’s Brown County Jamboree. At some point during the day, the assembled talent posed for a backstage photo. Among those in the picture – in addition to the Stanley crew – were Birch Monroe (Bill Monroe’s brother and park manager); banjo player Larry Richardson; and Harry Weger, a local DJ who was known as The Hoosier Folk Singer.

October 28 and 29, 1953, found the same quintet giving shows at the Taylor Theatre in Gate City, Virginia, and at the Fox Theatre in Kingsport. Two weeks later, on November 9, 1953, the entire Farm and Fun Time crew traveled to entertain patients at the veterans hospital in Johnson City. A photo in the Bristol newspaper revealed all of the current cast members: George France, Blake Stiltner, John Shuffler, Chubby Anthony, Wiley Morgan, Don Ray and Roy Mullins, Jack Cassidy, Ralph Mayo, Carter Stanley, Ralph Stanley, Smokey Davis, Fran Russell, Curley King, Dave Barnes, and Buster Pack.

Smokey’s last documented work with the Stanley Brothers came on January 22, 1954, at the Columbia Theatre in Bristol, Virginia. The occasion was the Friday Night Jamboree at the theatre. It included a mix of music, comedy, and a film.

Aside from a January 25, 1954, basketball game in Shady Valley, Tennessee, where Smokey and Ralph Mayo and the Southern Mountain Boys provided pre-game entertainment, the balance of Smokey’s work was the Friday Night Jamboree at the Columbia Theatre. From the end of January through mid-April, Smokey was a regular at the Jamboree, along with Red Malone and his Ozark Mountaineers.

An item in the May 22, 1954, edition of Billboard magazine gave notice that Smokey Davis and Roy Howington have joined the Al Cody show that is “currently working in Virginia, Kentucky and Tennessee.” Who Al Cody is, though, is a mystery.

November 10,1954, found Smokey paired once again with Red Malone, for a program at the George Washington School in Bristol, Virginia. The program was sponsored by the Bristol police department, for the benefit of the school’s PTA.

With a career that, as of 1954, spanned nearly thirty years, a November 19, 1954, appearance with Ralph Mayo and the Southern Mountain Boys at Bristol’s Paramount Theatre offered the first direct evidence that Smokey made music a part of his act. An advertisement for the show featured several photos, one of which was a band photo that includes Smokey. Another was a solo shot of Ralph Mayo and his fiddle. The last was a solo shot of Smokey at the WCYB microphone with a banjo/ukulele in his hands. A caption for the photo read: “You can’t get on top of ole Smokey! He can banjo. Milk a goat. Sings, too. And if he brings his first cousin – watch out!”

The appearance with Mayo at the Paramount marked the last documented performance that Smokey gave in conjunction with a hillbilly (bluegrass) band. Afterwards, with a few exceptions, Smokey dropped out of sight. Perhaps one of the most bizarre bits of news was the coverage of Smokey’s May 4, 1958, appearance at a grocery store anniversary. The caption to a newspaper photo read: “Clown Smoky Davis on roof of Cut-Rate Super Market tosses live chickens to crowd beginning to gather at Cut-Rate No. 3, West Sullivan St. Occasion marked the 24th anniversary of Cut-Rate Super Markets, now being celebrated at all of the Cut-Rate Markets.” And, a November 23, 1959, blurb in Billboard told that “Byron Gosh, manager of the All American Indoor Circus touring Tennessee and Kentucky, visited… Smokey Davis, Happy Arnold, Lee Allen Estes and Major Gloab, of Special Services at Fort Knox, Ky.”

The late spring and early summer of 1963 found Smokey traveling with the Community Free Circus which was based in the Houston suburb of Bellair, Texas. Smokey was billed as a clown act when the circus played in Bonham, Texas (April 8-10); Lawton, Oklahoma (May 31, June 1-2); and Oswego, Kansas (June 27).

Smokey’s next engagement was scheduled for Pryor, Oklahoma. A headline in the June 30, 1963, edition of the Bristol Herald-Courier told a different story: “Bristol Circus Clown Killed In Auto Crash.” The article related that “a well-known entertainer from Bristol was killed Friday [June 28] in a head-on collision near Vinita, Okla. Charles F. (Smokey) Davis, 55, who gained a reputation as one of the world’s most talented circus clowns, was driving a vehicle owned by the Community Free Circus when the mishap occurred at an intersection, about four miles from Vinita. He was en route to Pryor, Okla., for a performance. Two companions in his car were hospitalized with serious injuries at Tulsa, Okla. Davis gained recognition in the Bristol area as an entertainer for a local radio show; and appearances with a ‘medicine show’ in the area.”

The article went on to mention that Smokey was to be buried in Texas. However, his final resting place is in a cemetery in the town where he was killed. A simple headstone lists his name and date of death (incorrectly) as July 1963. No birth date was given.