Bluegrass Country Soul

Taking Us Back to 1971

For those in the bluegrass community who have been unable to attend live festivals since February because of COVID-19, a trip back to Carlton Haney’s Blue Grass Park in Camp Springs, North Carolina on Labor Day weekend, 1971, might be just the ticket.

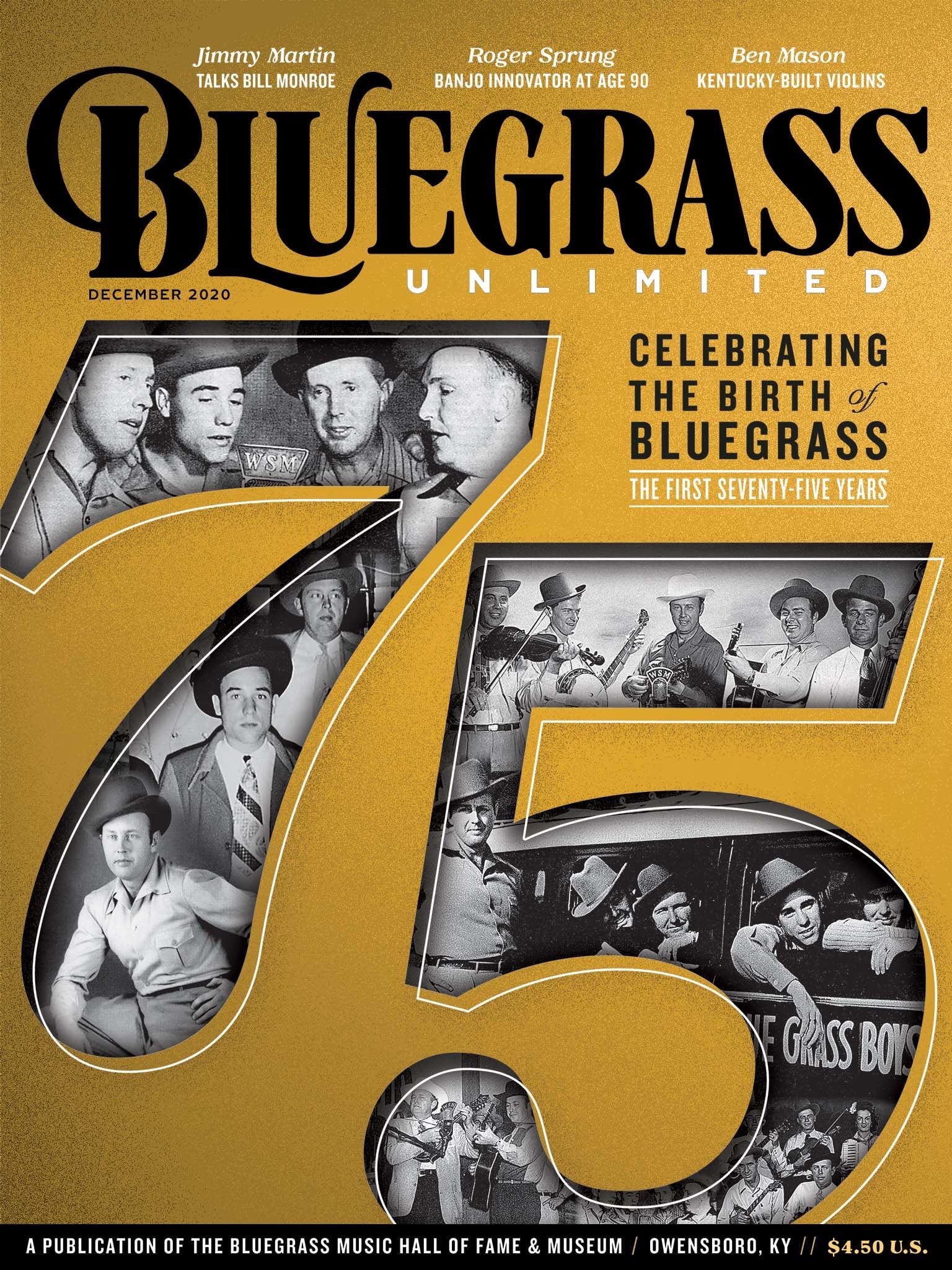

The remastered, boxed set version of the classic film released in late 2019 is a treasure. In addition to the original documentary on DVD/blue-ray, and a version with bluegrass historian Fred Bartenstein’s updated commentary track, there are interviews with Bill and Lola Emerson, Doug McCash, Akira Otsuka, Missy Raines, Ronnie Reno, and Ricky Skaggs – all who were there in ’71 and remember the festival fondly. There’s a 60-second trailer for the film, and also 30 minutes on “The Making of the First Bluegrass Movie,” featuring members of the 1971 film crew talking about the origins and production of the project. A bonus DVD features recent interviews with Del McCoury, who appeared at the festival with his band the Dixie Pals; J. D. Crowe, who was there with his Kentucky Mountain Boys; Everett Lilly, Jr., whose father and uncle were onstage as the Lilly Brothers with Don Stover and Tex Logan; and newgrass pioneer Sam Bush.

For memorabilia collectors there are reprints from 1971 Muleskinner News magazines, including the festival program, recipients of the Muleskinner News Awards Show, a poster and two fliers, and even a recipe card for Haney’s popular Brunswick stew, sold at the Blue Grass Park concession stand.

There’s an audio version of the commentary from Bartenstein, who served as festival director and emcee along with the late Bill Vernon at the festival in ’71, plus additional interviews on CD with Bobby Osborne (The Osborne Brothers), Robert “Quail” White (The New Deal String Band), and Sam Bush (The Bluegrass Alliance).

Digging deeper in the boxed set you’ll find a photo gallery of production photos and frames from the movie, plus a two-CD set of live stage audio. Twenty-four songs not included in the movie are presented from the New Deal String Band, Del McCoury & the Dixie Pals, Cliff Waldron & the New Shades of Grass, J. D. Crowe & the Kentucky Mountain Boys, the Country Gentlemen, the Bluegrass 45, the Wilson Brothers, and the Country Gentlemen, plus parts of the Saturday night Awards Show.

The centerpiece of the new collection is a beautifully produced, 168-page coffee table book entitled Bluegrass Country Soul – The Legendary Festival. Hundreds of color photos are included, along with memories of the festival from the musicians, audience members, and film makers. There are band features, production crew bios, a bluegrass bibliography, and the story of how the re-mastered film premiered and was donated to the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Owensboro, Kentucky.

The entire package is impressive in its authenticity and layers of comprehensive content. If you were at festivals in the early 1970s, you’ll feel like you’ve walked back in time. If you weren’t lucky enough to be there in person, you will feel like you have by the time you get to the bottom of the big, blue box. It’s like a set of those wooden Russian dolls that nest inside each other, revealing treasures inside of treasures.

At press time the producers of the new edition of Bluegrass, Country Soul announced the first pressing of the golden anniversary, legacy edition is nearly sold out and they don’t plan to manufacture more boxed sets. Instead, these pieces may be purchased a la carte: The Combo Pack (Blu-ray and standard DVD pus bonus DVD), a second edition Companion Book, or a two-CD set of additional music (stage performances from 1971).

The concept for the creation of the boxed set began with the goal of preserving the last surviving 35-millimeter copy of the film and donating a digital copy to the permanent collection of the Museum. According to executive director Ellen Pasternack and producer/director Albert Ihde, the project continued to grow after that.

Haney’s multi-day festival in 1971 was the first one in six years that did not include Bill Monroe, who had chosen to focus on his own events at Bean Blossom and elsewhere. Carlton knew he had to do something different to re-brand what he was doing in North Carolina. New, progressive sounds and the first bluegrass band to tour from Japan were featured, along with first-and second-generation artists in their prime (including Earl Scruggs and Chubby Wise from the classic Blue Grass Boys), and a country music star: Roy Acuff.

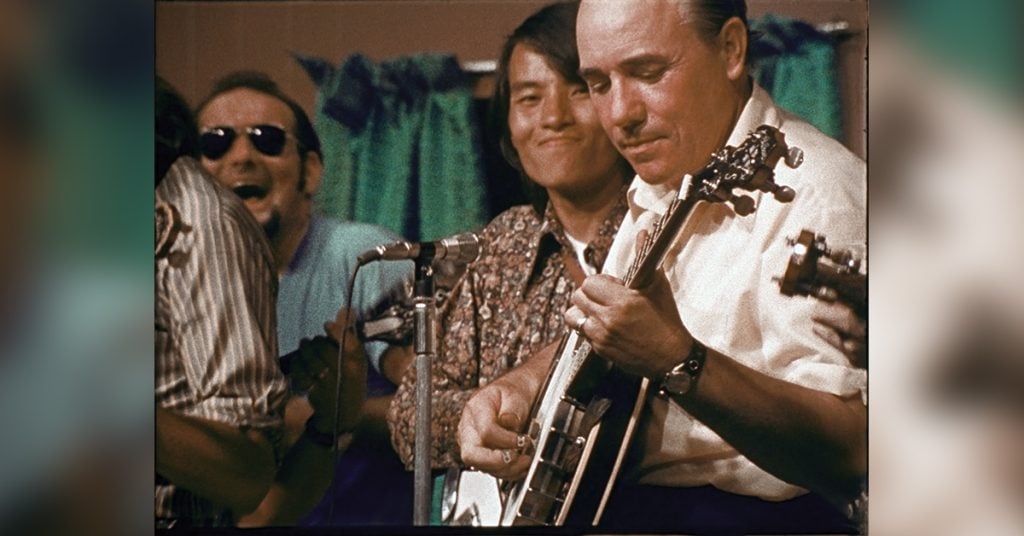

It’s hard to imagine a three-day line-up with more talented and diverse performers. Imagine sitting on a shady, red-clay dirt hill and enjoying the Earl Scruggs Review; Mac Wiseman; Chubby Wise; the Osborne Brothers, with Ronnie Reno singing the third part; the Country Gentlemen with Bill Emerson on banjo and Doyle Lawson appearing for the first time with the group; and Ralph Stanley with Ricky Skaggs, Keith Whitley, Curly Ray Cline and Jack Cooke. And then there was Roy Acuff, with Bashful Brother Oswald and crew; plus Jimmy Martin with his sons Timmy and Ray, a young Alan Munde on the banjo, and Gloria Belle rocking the electric bass. The fabulously entertaining and talented Bluegrass 45 from Japan thrilled the audience, along with the J. D. Crowe band that pre-dated the New South—including Tony Rice on guitar for the first time with the group. Tex Logan absolutely wears out the fiddle on “Black Mountain Rag” in the opening strains of the film, alongside Don Stover’s signature banjo and the wonderful Lilly Brothers. It’s a treat to see and hear a young Del McCoury just after the release of his first album and a young Sam Bush with Courtney Johnson and Ebo Walker, who would a few months later form the New Grass Revival.

“Bluegrass Country Soul shows just where bluegrass was when it started to grow and reach new audiences,” Ricky Skaggs notes. “It captured that moment in time brilliantly, I think, frozen like a leaf in ice. I’m just so thankful that it got recorded when it did, because it includes so many of the old fathers, the people who really gave their life for this music.”

“This was the weekend it all changed,” Sam Bush noted.

Like reading a good book, different details stand out each time the film is viewed: Bobby Osborne’s scalding tenor lead on “Ruby” and Sonny’s joyful approach to the banjo (with six strings); unforgettable and unique vocals from Charlie Waller, Mac Wiseman and Jimmy Martin; the combustible energy of fiddlers Tex Logan, Curly Ray Cline, Tater Tate, and Chubby Wise; J. D. Crowe ripping through “Train 45;” and the unmatched tone of Earl Scruggs and the obvious pleasure he took in playing music with his sons, Gary and Randy. Be sure to catch the look on 9-year-old Missy Raines’ face as she listens to the Bluegrass Alliance sing “One Tin Soldier.” Watch the crowd’s reaction when the Bluegrass 45 plays “Feudin’ Banjos” with their instruments behind their heads and when the New Deal String Band launches into a bluegrass version of “Love Potion Number Nine.” And then there are the charming accents and storytelling behind the stage from the Lilly Brothers, and the talented musicians at impromptu jam sessions in the fields.

Enveloping the entire weekend was the passion Carlton Haney had for bluegrass music and his vision for its future. “I plan to develop Camp Springs and Blue Grass Park, build a Hall of Fame, Library and Archives, and a recording studio so that all acts can record and leave that to the musicians,” Carlton prophesies in the film, “and anything else they need me to do they can ask me and I will.” Haney, who was inducted into the Bluegrass Hall of Fame in 1998, was not far from the mark. These things didn’t come to pass at Camp Springs, which has recently revived the Labor Day weekend festival under new ownership, but they did happen. There is a Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame and Museum to be proud of in Owensboro, KY, which also includes the Kitsy and Peter V. Kuykendall Research Library and the 450-seat, state-of-the-art Woodward Theater for live and televised programs. There is an IBMA Awards Show and Momentum Awards for rising stars on the horizon, similar to the “Best” and “Most Promising” categories Haney and Bartenstein introduced in the 1971 Muleskinner News awards. The educational efforts embedded in the Camp Springs vision are still going on through the efforts of the Foundation for Bluegrass Music and the many festival-based bluegrass academies and camps that share bluegrass music with the next generation.

There were little kids everywhere at Camp Springs in 1971, following their favorite artists around, leaning against walls and looking around corners backstage to get a close-up view of the music they were drawn to. The purpose of bluegrass festivals, according to Haney and Bartenstein, was to teach the audience about the music as well as celebrate the artistry of the musicians present. Hearing good, live bluegrass is still something that changes lives and builds community. The introduction of multi-day festivals also supported the next two or three generations of bluegrass bands financially.

Country people and fans from the cities got along fine, enjoying the music they all loved. Carlton Haney referred to them as “the long hairs” and “the short hairs.” In a time of political and racial division in the world today, perhaps we should look to the power of music to build community, the way it happened in the equally contentious summer of 1971.

There weren’t many bluegrass festivals in the early 1970s, and Haney was close to tears when it was time for folks to pack up their tents and instrument cases and head home, knowing he wouldn’t see many of them for a year. “It hurts me to see them leave,” he said in the film, “but I know most of them have enjoyed themselves, and they have heard the best music in the world, played by the greatest musicians in the world. And that’s bluegrass music, and that’s a bluegrass festival.”