Home > Articles > The Tradition > Birmingham’s Three on a String to Celebrate Half-Century of Continuous Entertainment

Birmingham’s Three on a String to Celebrate Half-Century of Continuous Entertainment

All Photos Courtesy of Three On A String

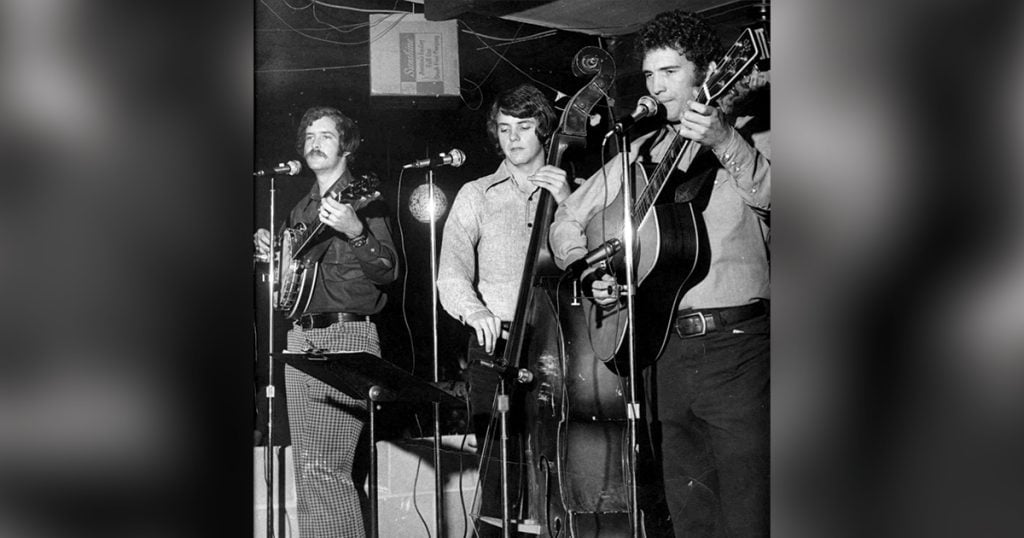

Those who are old enough, and lucky enough, to have walked on a weekend night down several deep steps into the Lowenbrau Haus in Birmingham, circa 1972, walked into an enchanted grotto full of music, laughter, thick ropes of smoke and a band called Three on a String. The memories are indelible. Elwood P. Dowd, in the movie Harvey, says something like, “Bars are wonderful places, full of large stories and big times, because nobody ever brings anything small into a bar.” The Lowenbrau held 150 people, 40 more than the law allowed—but it was bigger, somehow. The Lowenbrau was like that because Three on a String is like that. Was and is, through fifty years of continuous entertainment.

“The String” took the stage at 9, and for five hours made the world go away. Jerry Ryan, Bobby Horton and whomever was on bass at the time (mostly Andy Meginniss) threw to the crowd thumping bluegrass peppered with skits, wit and jokes as smoke swirled, thick as London fog. It was, after all, the 1970s and the Lowenbrau, says Jerry, “still holds the record for smoke in all categories—volume, density, age. You name it.”

After the first set came what Jerry called “Rolling Time.” The third set was “Hard Rolling Time.” And just about midnight, when the avid crowd thought sadly the last set was ending, Jerry said not to leave. The moment had come for “Extremely Hard Rolling Time.” And that was the best. It was the time when the String might be joined by whatever other Bluegrass band might be playing in the area. All Bluegrass bands are friends.

And one magic night, the eternal Odetta stepped out of the audience and onto the stage. Jerry doesn’t remember what song she sang. “It was gospel, though,” he said, “and I don’t think anyone breathed for about five minutes. It was that good.”

The half-vaudeville, full-throated, sweet picking show produced by the String is that good, too. The band’s repute was such that one night Ray Stevens showed up at its Stage Door venue, after a show at the State Fair Park with Porter Wagoner, and that entailed an appearance on the national TV Ralph Emery Show.

Unique is a word sorely misused. Unique means one. There is no almost unique. Three on a String is unique and has been for a half-century. Come the first weekend in August, if the plague abates, the original String and most of its venerable retinue will hold its 50th reunion celebration. Jerry Ryan, Bobby Horton, and Brad Ryan will take the stage at the Birmingham/Jefferson Civic Center and Three on a String will perform its bluegrass, old-timey music and homespun, hilarious act just as it has done more than 20,000 times over the 50-year span. If that’s not a record, it’s close enough.

There will be a show Friday night, a Saturday matinee and the Saturday night finale. All will be sold out. And when the String takes the stage, the only thing the audience can be certain about is that it’s about to get wildly entertained with fun and much music with the pulsing bluegrass backbeat. It’s a music show. It’s a nightclub act.

The String has inhabited four ever-growing venues in Birmingham, and played others throughout the South, cobbled with occasional road trips that carried it an astonishing half-million miles. At least. The band has opened on occasions for President George Bush (the first) and President Ronald Reagan. It opened once for Red Skelton, and once fronted for Bill Cosby at the Chattanooga River Band Festival, playing in front of 101,000 fans. The band has played for governors of Alabama and those who would become governors. Captains of Industry, as well as politicians, book the band for annual events. The Chattanooga Festival is at the top percentage of Jerry’s memories. “Extremes may be the best,” he said. “A sea of faces will never be forgotten.”

And there was the Saturday night when black comedian Jimmie Walker, “Kid Dyn-o-mite” from the hit sitcom Good Times, opened for the String at Walker College in Jasper, Alabama. The crowd of 750 was white conservative, and the reception for Walker was cool at first. He overcame it with lines like, “I was raised in the Bronx but like most of you, most likely, I never developed a taste for chitlins. They taste like chit.” After an after-the-show reception, Walker told Jerry that playing to crowds like the one at Jasper was his favorite thing to do because it was personal outreach for him. “I feel like an ambassador,” he said.

The String never stagnates, but ebbs and flows with the times and genres. Eighteen musicians have been with the band over time, but always there in the center have been Jerry on guitar and harmonica, mostly, and Bobby on banjo, and fiddle, and Dobro, and doghouse bass and pennywhistle and on his renowned bluegrass trumpet.

And the band reflects the immortal, immutable sound of bluegrass music and its ups and downs. “We start every show with the promise that we want everyone to have fun, because that’s what we’re going to have,” Jerry said. “Every show. Because that’s what we are and that’s what we do. There’s nothing like playing for a group that never heard of us and have the show end with a standing ovation. It’s special.” Most of the band’s shows have accomplished that very fact.

It started in fall, 1970. Jerry was finishing conditioning drills with his freshman basketball team at Birmingham’s Samford University when a logger walked up to him. Well, he looked like a logger, in a flannel shirt, khakis and brogans. In reality, he was a public relations guru named Warren Musgrove, the writer for upscale, Baptist-straight Samford. The only giveaway was that he carried a small notebook and the sharp end of a broken pencil. “Are you the coach that plays the guitar,” he said, “and don’t you have a friend who picks the banjo?”

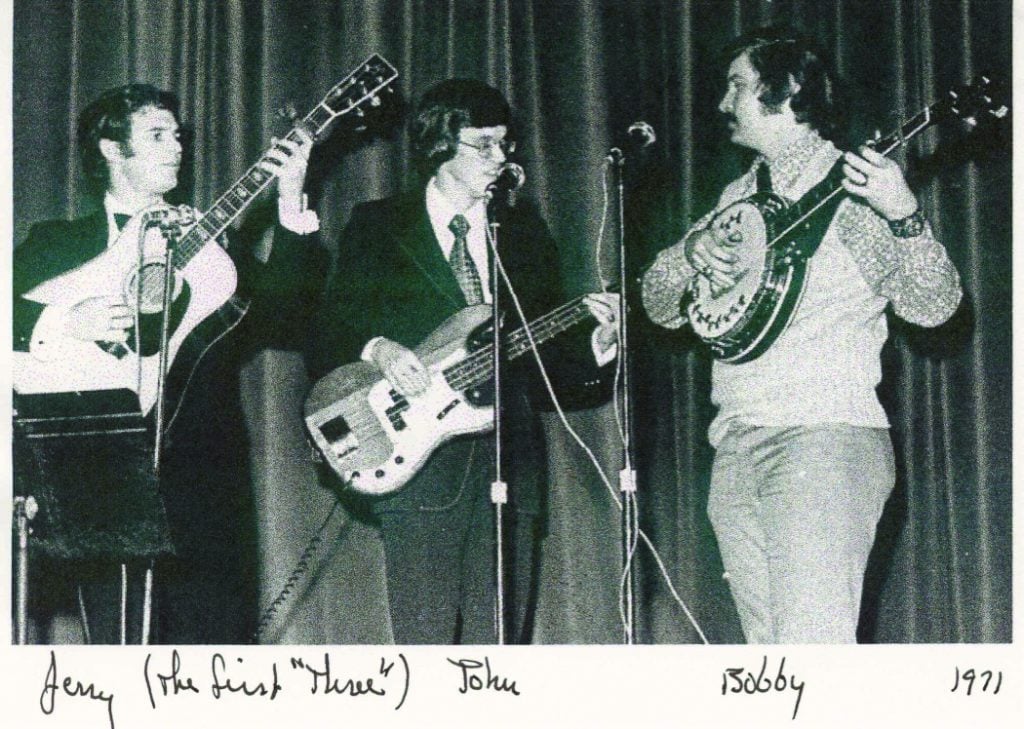

The standard answer for novice players in those days was, “A little bit.” Jerry said, “A little bit.” Bobby Horton was a member of the Samford Marching Band. “I’d like you to play at my folk festival up at Horsepens 40 on Chandler Mountain near Steele, Alabama, about an hour or so from here,” he said. “Let me get a publicity picture of you two and you can play in October.” Musgrove paid them a total of $15.

And so it began. Just Jerry and Bobby, playing at Warren’s arts and crafts throwdown. They knew seven folk songs. They can’t tell you all of them, but they included “Rolling in My Sweet Baby’s Arms” and “Foggy Mountain Breakdown.” Bobby was new to the banjo, but it was a hot instrument in the early 70s. The bluegrass festival in Alabama wasn’t born exactly yet, but it was in labor.

A sax player who owned the Alabama Music Store in Birmingham was there. He told them he felt they had promise and should entertain the notion of adding a bass player. “And someone who can sing,” he said. By that, he meant harmony, “to round out the sound.” They found tall John Vess, who had a great tenor voice but hadn’t a clue about a doghouse bass. And so formed the original. Not one of the 10 different upright bass players in the 50-year history could play a bass when he joined the band. Each had the high lonesome harmony sound, though, and had it more than somewhat.

Not long after Vess joined, the band took its seven folk songs onto the stage of the Lowenbrau, a big basement under the Jack and Jill Shoestore in Homewood about a mile south of Vulcan’s bare butt as he overlooks the city of Birmingham. “We learned all four of the top banjo songs on the radio at the time,” Jerry said. “We did ‘Foggy Mountain Breakdown,’ ‘Rocky Top,’ ‘Dueling Banjos’ and the theme from The Beverly Hillbillies. We had no trouble finding work. The bluegrass craze was huge.”

The band flirted with names for the group when it started the club routine. Bobby and wife Lynda and Jerry and wife Kay met to discuss. Peanut Butter and Jerry didn’t chime, nor did Coach and the Fast Break. Then Lynda said, “Well, there are three of you and you all play stringed instruments. What about Three on a String?” Nobody said no. And so it was. So it is.

The show Jerry and Bobby developed in 1972 for the Lowenbrau is mindful of the opening scene for the classic movie Cabaret, set in Germany the year Hitler leads it—with a death’s head grin—into the horrors of WWII. The masterful Joel Grey as the fey master of ceremonies invites people into the madcap club where they will escape for a while the madness and burgeoning troubles of the outside world. Alabama, at its worst, was never Germany. But Three on a String’s basic message was to take the deep steps down from the parking lot to the Lowebrau’s atmosphere and forget your troubles.

“When we started,” said Jerry, “my coaching instinct kicked in. It was like being in a football game with the audience and I was the quarterback calling plays. If we played slow stuff that wasn’t working, we changed the plays. We’d play a fast song or two, or run a skit or tell a joke, and hope to score. We did, most of the time.”

As Jerry says, “You had to know where you’re going to find the alley to the entrance to an intimate club that captured the spirit of folk music and a new-to-some music craze called bluegrass that was beginning a reemergence in the nation.”

Emmylou Harris began her career at the Lowenbrau. Folk singers Richard and Jim started there. Starcrossed Steve Young (“Seven Bridges Road”) started there. As the String moved on to Birmingham venues like The Stage Door and Cadillac Cafe, it would share the stage with The Red Clay Ramblers, Front Porch String Band and Mason Williams. And Bill Monroe. There is no better music.

Always, there were Bluegrass Festivals for the group. HorsePens 40 spawned festivals around Alabama like Brushy Creek, Froggy Holler and others. There was also the Three’s “symphonic” period when it traveled with the Alabama Symphony and performed with the Longmont Symphony near Denver. Its longest trip was a gig in Saskatchewan, all their trips in their van, “Skippy.”

“We thought our club days were over,” Jerry said. “Then my brother Terry bought The Stage Door, near the Lowenbrau. Originally, we turned down his offer to be the host band, but somewhere on that 39-hour drive back to Birmingham, a steady gig became a good idea. Eventually, we bought the club and played there 10 years.”

In its salad days, it wasn’t unusual for the band to perform four or five shows a day. The band has produced a dozen albums and four original songs, though not yet a hit record (unless you count “The Little Blue Nun” that topped the charts in Birmingham), but that’s not the kind of record that surrounds and encompasses its uniqueness. Its records are reflected in years and people and miles and smiles.

Also, each member has a college degree and had it when they started making music. Jerry has a master’s in education, Bobby in accounting and Brad and Andy each have business diplomas. Not too long after taking over the Lowenbrau they were putting in so much band time that in effect they were working two jobs.

Jerry and Bobby each said they felt secure, finally, in the entertainment business. They kicked free of the so-called “straight jobs.” A week after quitting his day job, Jerry said to wife Kay, “I don’t know how many people get to make a living doing exactly what they want to do, but for at least a week, I’m one of them.”

Three on a String was one of the first inductees into the Alabama Bluegrass Hall of Fame. It is nominated for induction into the Alabama Music Hall of Fame in January, 2022. On May 17, the Alabama Legislature passed a joint resolution commending the band for its half-century of excellence and recommended its inclusion in the AMHOF. “This should have been done long ago,” said one.

“We consider it a very great honor even to be considered for the Alabama Music Hall of Fame,” Jerry said. “What greatness is in that place. They are immortals. We are humbled by the thought.” It would be fitting. Maybe the road is narrowing some for the group. The plague sidelined it some, but the String still is hungry to play and perform. It’ll keep going for a while. In fact, it might never go away.

It has been discussed that Brad, who reluctantly joined the band 35 years ago, and who has been with the band longer than any other bass player, might be interested in taking it over someday, adding and evolving as necessary. “Brad didn’t want to play the upright bass because his peers considered it uncool,” Jerry said of his son, “until he learned the musician who played the upright got paid. And then there was the night in the Ryan family den when the Whites, with Ricky Skaggs, sat around with us and played any and every song the family requested. What a night that was.”

But there is very likely always to be some of the same bluegrass tunes, the fiddle, banjo and guitar. And the good times. The laughter. Always.