Home > Articles > The Artists > Billy Cardine

Billy Cardine

Resophonic Explorations

Billy Cardine has explored the possibilities of the square-neck resophonic guitar far beyond the genres of bluegrass, folk, country, Americana and blues. While musical explorations that push the outer bounds of genre are not typically embraced by bluegrass hardliners, Cardine is a musician who knows how to reign in his expansive musical abilities to tastefully fit any musical situation. He knows how to play to the song melody, to the lyrics, and to the feeling being expressed by the singer. And he knows how to fit seamlessly into the feel and groove being expressed by the other musicians he is performing with in any given musical setting. The instrument that he uses to express his highly developed musicianship just happens to be the Dobro.

Background

Billy Cardine has been completely immersed in music from the time he started learning how to play the piano at the age of three. He said, “I was the kid who actually liked to practice. My mom would have to yell at me to get me to leave the piano and come to dinner. I enjoyed learning and practicing.” Billy studied classical music on the piano and performed at recitals all the way through his high school years. Additionally, he said he “messed around with” other instruments in the school orchestra—mainly cello and clarinet, but whatever the band leader needed.

When he was twelve years old, Billy started learning how to play the guitar because he wanted to jam with his friends and he couldn’t cart his piano to jam sessions. Although there were portable keyboards, he said that he didn’t think that the portable electric keyboards of the day sounded very good. When he started to play the guitar, he enthusiastically dove head-first into all things related to the acoustic and electric guitar. He studied Stevie Ray Vaughn, Joe Satriani, Steve Vai, Buddy Guy, B.B. King and jazz guitarists. He said, “I was addicted to guitar.” At one point, while still in high school, Billy saw an ad in a guitar magazine for Steve Vai’s ten-hour guitar course. He ordered the course and when it arrived he would stay up all night going through all ten hours of the course.

Billy graduated from high school in 1993 and after attending community college for one year he entered James Madison University in his home state of Virginia. During his first year of college he had to have carpel tunnel surgery on both wrists due to his excessive amount of practice and playing. He said, “I was playing like an athlete, but not acting like an athlete in terms of taking care of my body, so I burned my wrists out. Through that situation, I learned how to train, and gratefully those issues haven’t resurfaced.”

Discovering the Dobro

Before entering James Madison University, while he was taking classes at Northern Virginia Community College, Billy made friends with one of his classmates in a music theory class. Billy said, “There was one guy in class that I got along with and we would talk after class and do our ear training exercises together. He was in a band at the time and told me that the band that he played in had a really good guitar player. At the time I brashly thought to myself, ‘Everyone knows a good guitar player,’ and didn’t think much of it.” It turns out that Billy’s friend from school was Ronnie Simpkins and the good guitar player that Ronnie played with was Tony Rice.

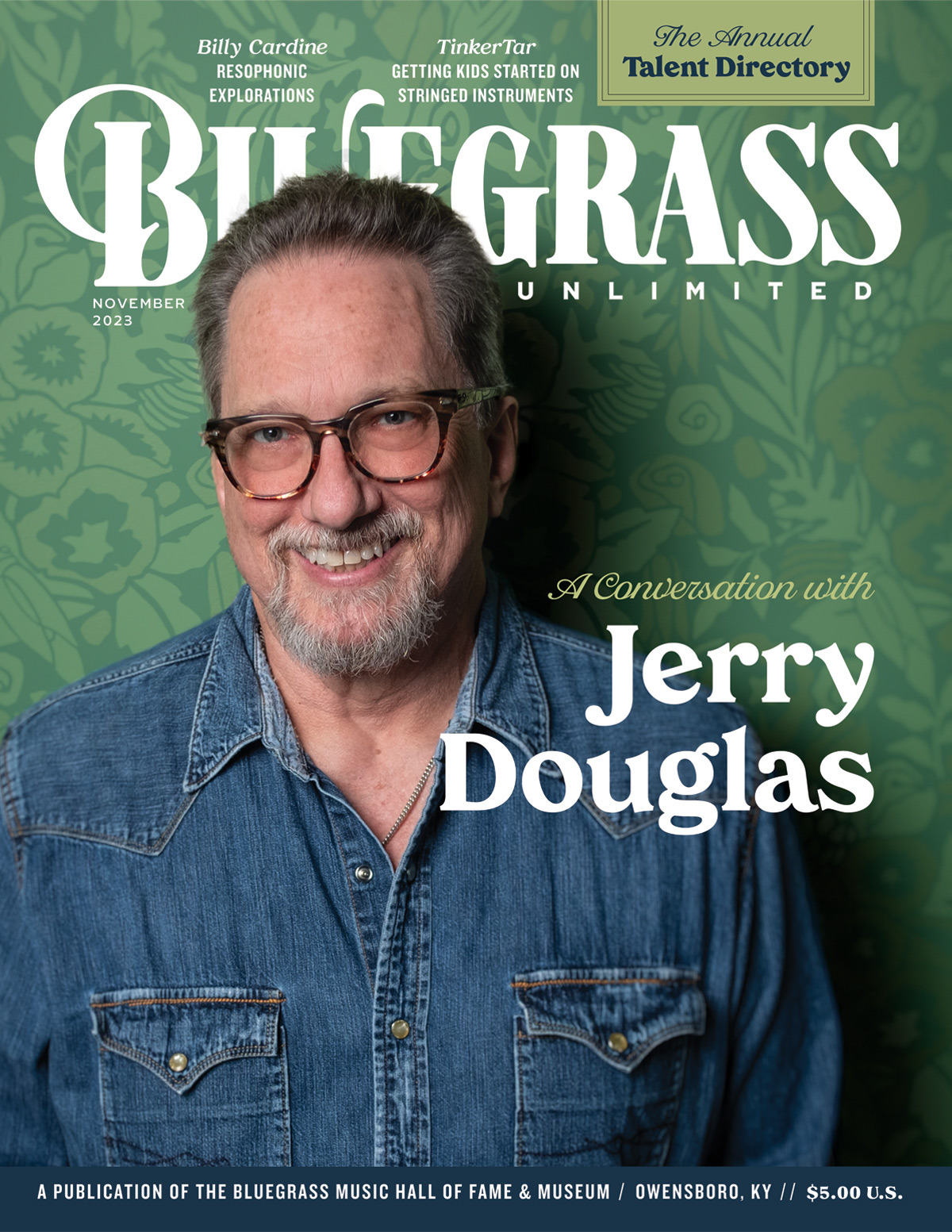

After Ronnie Simpkins gave Billy a copy of Tony Rice’s Cold On The Shoulder album, Billy took it home and stayed up until two in the morning listening to it. He said, “That day was when I heard the Dobro for the first time. Excited beyond measure to hear Jerry Douglas for the first time, I went to a music store in Sterling, Virginia the next morning to buy a Dobro. I had seen one, but I didn’t know what they were. I didn’t know the difference between a round neck and a square neck. I bought a round neck and was wondering why the bar was buzzing off the fretboard.” Once he finally figured out what the problem was, he purchased a square neck instrument.

One reason that Billy was attracted to the Dobro, other than hearing Jerry Douglas play on the Tony Rice album, was that he knew that he was having hand issues playing the guitar and thought that holding the bar and not having to use his fingers in the same way he used them on the guitar would help with his wrist problems.

Regarding his learning process, Billy said, “Learning to play the Dobro for me was born somewhat out of ignorance. I had pretty much only heard Jerry play and I assumed that that was just how you’re supposed to play the Dobro. I didn’t realize that he was kind of a singularity. I bought his Slide Rule album and started transcribing his solos. At the time, I had little business playing ‘Ride the Wild Turkey,’ but I had developed a good ear and could find all the notes. I was still far away from being able to play it really sweet, but some progress was being made. Fast forward some years and Jerry has become a great friend and mentor, inspiring me both musically and personally.”

In addition to transcribing every Jerry Douglas solo note-for-note off of the Slide Rule album, Billy also transcribed other musician’s recordings and put what they were playing on the Dobro. He said, “I transcribed Béla Fleck, Stevie Ray Vaughn and a lot of other non-Dobro players. I transcribed sax solos, violin solos, Gypsy Jazz music…anything I heard that I liked. I had a folder on my computer titled ‘To Assimilate.’ Any musical phrases that I heard that I thought were cool and wanted to learn, I’d throw into that folder. When I had time, I’d go through these nuggets and learn them and play them a thousand times.”

While Billy was at James Madison University he studied computer programming, but also took music classes. After graduating from JMU, he moved to Charlottesville, Virginia and joined Larry Keel’s band (from 1998 to 2000). During that time he also met John D’Earth, a jazz instructor at the University of Virginia, and studied with him. Billy said, “He was the real deal! He taught me how to really learn the neck of my instrument. That was a huge part of me pulling things together. I had tried a lot of ways to learn the neck, but with his method I got the full lock. Everything became clearer. It was really helpful for what I like to do.”

Not long after starting to learn how to play the Dobro, Billy attended a Dobro workshop at Merlefest that was taught by Mike Aldridge. He said, “That was awesome! When I learned that he lived in the Washington, D.C. area, I went to talk with him after the workshop and ask if he taught lessons. He said that he did and from that point I went to his house to study with him for years. I did that from the late 1990s up until a few months before he died (2012). I recorded my Six String Swing album for him and Mike wrote a blurb for the liner notes just before he died.” Billy—always on the lookout for an opportunity to learn—also took lessons with Rob Ickes, Sally Van Meter, and Stacy Phillips. Additionally, Billy formed a relationship with Tut Taylor. He said, “I knew Tut for ten to twelve years and we got close. Tut was always in my court and I appreciated him as a mentor.”

When asked if has ever had the opportunity to perform with Jerry Douglas, Billy said, “We were playing at the Bijou Theater and Tony Rice and Jerry Douglas were on the bill. Jerry invited me up to do a duet with him. He was plugged in and I was playing through an SM57. I thought, ‘I could really get destroyed with him being plugged in.’ But, I was blown away and touched by how sensitive he was to that situation. He matched my intensity and he interacted with me in a way that leveled the playing field.”

The Biscuit Burners

In the world of bluegrass, Billy Cardine is probably best known for the time he spent performing with The Bisciut Burners. After he left Larry Keel’s band in 2000, he said a number of his music friends in Charlottesville had left the area and that the music scene they had amongst their friends was changing. So, he and his wife Mary decided to move to Asheville, North Carolina. It was during their early years in Asheville that the Biscuit Burners came together.

Billy said, “At that point, Mary and I did nothing but Biscuit Burners for six or seven years.” Highlights of his years with that band include performing on the Grand Ole Opry with Vassar Clements, playing the Bonnaroo festival, playing the first non-classical music concert at the Kennedy Center Opera House after its renovation, traveling through Europe, and playing the Americana Music Festival.

The Biscuit Burners recorded three albums, The Biscuit Burners (2004), A Mountain Apart (2005) and Take Me Home (2008). Members over the years included Billy Cardine, Mary Lucey, Shannon Whitworth, Jon Stickley, Lizze Hamilton, Rocky Whittington, Odessa Jorgensen, Wes Corbett and Dan Bletz. The group stopped performing in 2009. Bluegrass Unlimited ran a story about The Biscuit Burners in April of 2007.

World Music

Regarding his interest in various musical styles from around the world, Billy said, “I have always been into every kind of music and I have collected folk music from around the world since I was a kid. I tried to discover music from every country I could. Whenever I ran across organic native playing that was from the heart—not overproduced —it was all cool to me and I heard the common threads, regardless of instrumentation. I didn’t have a hyper-focus on listening to just Dobro playing.”

In about 2001, Billy heard that the world-renowned Indian slide guitarist Debashish Bhattacharya was teaching a special semester of music in New York City. He said, “I first learned about Debashish when I was in a music store in New York City and there was a TV in the store that was playing a VHS tape called The Word Of Slide Guitar. When the segment came on showing Debashish playing, I thought ‘What is this!’ I came to realize that he was kind of like the ‘Michael Jordan’ of Indian music on slide guitar. His ability to translate his culture’s music onto slide guitar is remarkable. He is the most technically advanced slide guitarist that I’ve heard.”

When Billy found out about Debashish’s class in New York, he tracked down the event’s program director and asked about enrolling. It was to be a two month long class and the director said there were openings and asked if Billy needed a place to stay. He was told that there was an available room in the teacher’s housing building. Billy ended up living right next door to Debashish during his two month stay in New York. He said, “Our doors were right next to each other in the same hallway and we shared a kitchen! We became real tight. I remember one morning I woke up early and I was practicing in my room. About 40 minutes into it, Debashish came in and said, ‘Everything that you have been playing for the last 40 minutes is wrong!’ That’s when I knew I was actually going to learn something.”

When asked about what he learned from Debashish that he could apply to the Dobro, Billy said, “I learned how to access music through his techniques and it allowed me to reach closer to what I want to do with my music. I learned how to be smoother and really be in the groove from Debashish. I can now play old-time music all the way up the neck with feeling. The Indians don’t play in zones across the neck like we do on the Dobro. They can play everything on one string and go up the neck past the fret markers and stay in tune at crazy tempos. Six String Swing never would have happened without the techniques that I learned from Debashish. I learned how to approach the Dobro with a different mindset. While I love it, I knew I would never aspire to be an Indian Classical musician, but through their technical approach, heart and nuance, I’ve been able to get closer to my own vision.” Billy showcased some of the music he learned from Debashish on the 22-string Indian slide guitar when we was performing with the Biscuit Burners.

Another style of slide guitar music that Billy has been exploring lately is the Hawaiian style. He said, “I was teaching at Rob Ickes’ ResoSummit and Rob put me together with Hawaiian steel guitar player Bobby Ingano. We rehearsed together to play the show and that turned into a jam every night until about four in the morning. It was me, Bobby and a great rhythm guitar player, Joseph Zayac. I was already feeling the Hawaiian vibe and thru hanging with those guys I really got the bug. I bought an eight-sting frying pan guitar and have spent my spare time this year transcribing and arranging on that instrument. I was thrilled to go to Oahu and perform at the Waikiki Steel Guitar Festival.”

Billy takes note of the movement that was made from the Hawaiian slide guitar to country and bluegrass music in the 1930s and 40s. He said, “In the early 1900s jazz was developing and records were popping up. Somehow that music made its way to Hawaii. They were informed by early jazz and got some of their sensibilities from jazz. A Hawaiian musician named Sol Hoopi’i developed technical prowess and was the torchbearer of that era. He could really play. Hawaiian music became popular all over the world in the 1930s. They were selling lap steels at Sears. Brother Oswald and Josh Graves were informed by the music on the Hawaiian scene. It was an inevitable melding. You can hear the Hawaiian influence, especially in Brother Oswald’s playing.”

Back to Dobro

After exploring slide guitar instruments from other cultures, Billy likes to bring it all back to the Dobro. He said, “I like the neutrality of the Dobro. The G-tuning is inert so I can make it say what I want it to say. The different tunings that you find on other slide instruments can bring you to a place quickly, but also make it hard to leave that place. For example, they might pour the Mai-Tai for you, but it can be hard to get out of the Tiki Bar. To me, the Dobro feels more malleable. I can move around more freely on the Dobro than I can with the other options in the slide guitar world. The Dobro feels like a blank slate. The Dobro feels like home.”

Although he has experimented with other slide instruments and many styles of music, Billy brings it back to the Dobro and is now also bringing the Dobro to other cultures. He is currently working with a band called The Bluegrass Journeymen who travel to other countries to perform their music from home and also interact with musicians from the countries that they visit. So far, the Journeymen have toured in India, Nepal, Bali, and Kauai. They will also be traveling to Nepal in November 2023. The band’s website lists its current members as Patrick Fitzsimons (mandolin), Coleman Smith (fiddle), Charlie Mertens (bass), Mary Lucey (banjo/vocals), Summers Baker (guitar), Billy Cardine (Dobro), and Nabanita “Bonnie” Sarkar (ukulele and vocals). Casey Driessen (fiddle) and Matt Manefee (banjo) have also performed with the band. Regarding singer Nabanita Sarkar, Billy said, “She is an Indian singer who grew up in her local tradition but also sings Jimmie Rodgers and Doc Watson songs!”

Currently, Billy also performs with his wife Mary Lucey and singer/songwriter Anya Hinkle. He also fronts his own band titled The Billy Sea, which includes acoustic Dobro, drums, electric bass, sax, bassoon. Billy calls what The Billy Sea does “Beautiful, sensitive and intense music that doesn’t fit into any one wheelhouse.” Prior to the COVID pandemic, Billy and his wife were performing with another married couple, Shelby Means and Joel Timmons, in a band called Lover’s Leap. Billy said that the band came together after the two couples were put together by a festival promoter. Billy said, “We all met the night before the festival and put a set list together. We played the set and it was so easy, we decided to form a band.” That first show was in the shadow of a cliff that is called Lover’s Leap, hence the name of the band. They intend to continue performing and consider the project long term, but currently Shelby is touring with Molly Tuttle.

Billy also does session and record production work, having been “the AV guy since I was in kindergarten.” He has a recording studio in his home and collaborates with musicians from around the world. He is passionate about writing parts and arranging music.

His new efforts include an online portal for teaching some of the ‘path less traveled’ music for the Dobro including jazz and swing, meant to be released sometime in 2024. Additionally, he will release his newest recording Old Crooked Mountain in 2024, a project which puts the acoustic Dobro at center stage with brilliant rhythm sections, including drums, bass, and horns of all sorts, produced by the prolific Bill Stevens and even features a track with his sister the amazing Becca Stevens.

Although Billy Cardine has studied music from many genres from around the world, he brings it back to the Dobro and doesn’t try to push what he knows or can do into musical situations that don’t call for it. He said, “When I work with a singer, whatever they sing, that is what I try to play.” That is what being a great musician is all about.