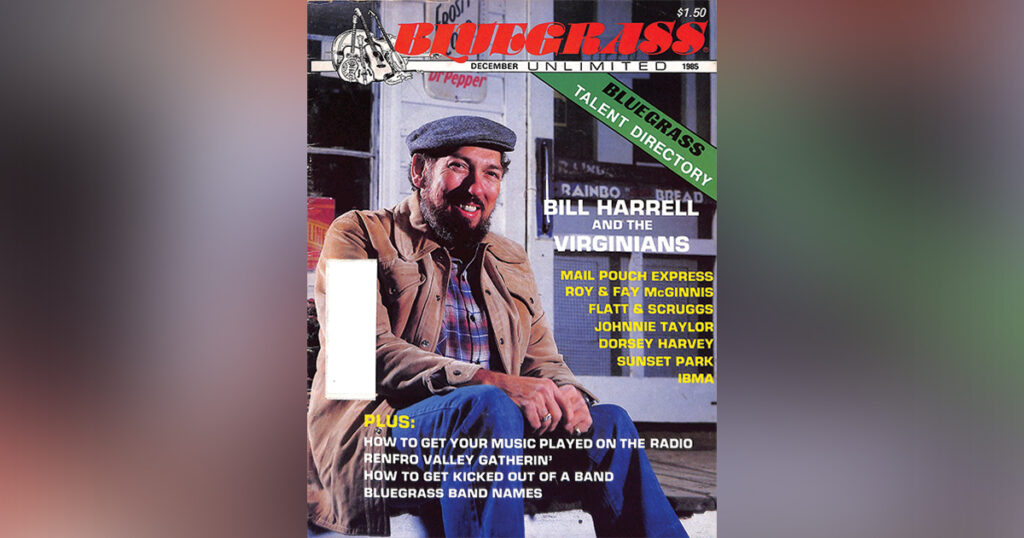

Home > Articles > The Archives > Bill Harrell and the Virginians

Bill Harrell and the Virginians

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

December 1985, Volume 20, Number 6

By J. Wesley Clark & J. Michael Hosford

[Editor’s note: In March of this year, after the interview for this article was done, Paul Adkins joined the Virginians playing mandolin, Paul was out of the music business for a year and a half prior to joining the band, but according to Bill, “He’s blending so good, I just couldn’t be happier.

“Paul has really done his homework since joining us. He’s become an important part of my organization.”

Paul has recently completed an album for Webco, which includes Bill and the veteran Virginians, as well as Paul’s wife Janice singing harmony.]

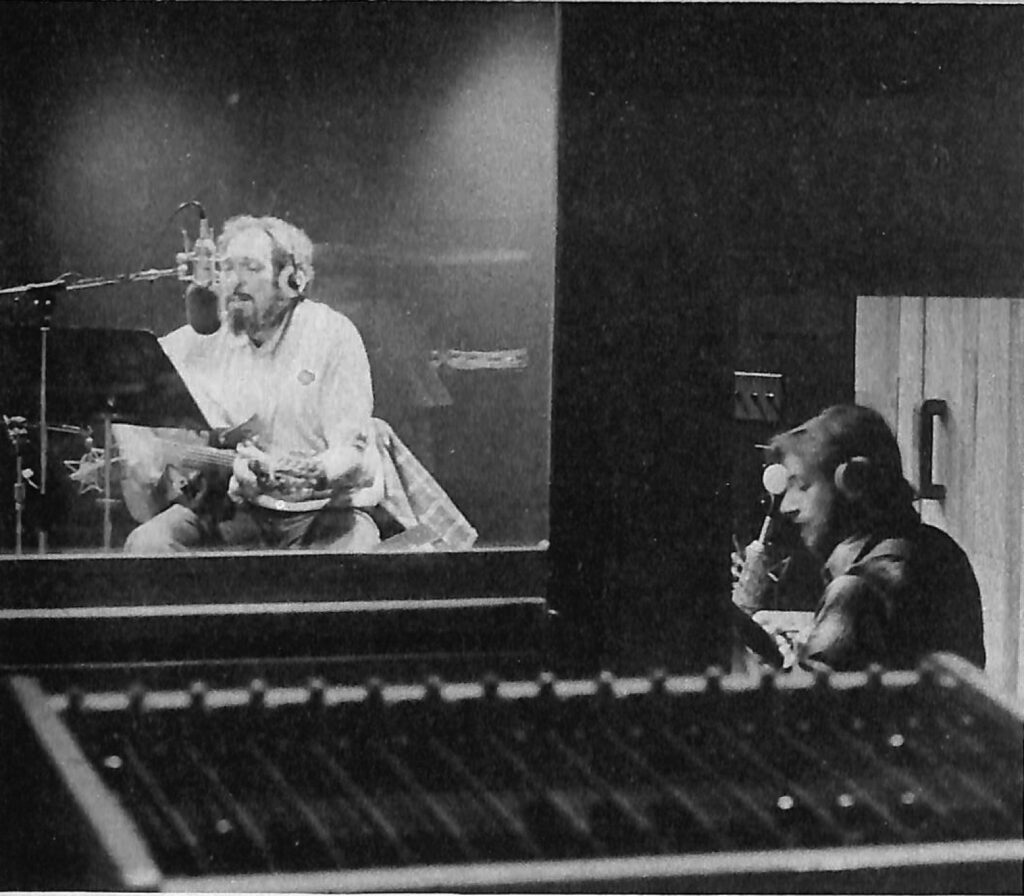

Across a dusty road from a concrete plant in Springfield, Virginia, is the Bias Recording studios. I found it after driving past it three times on a windy Saturday afternoon in early spring. The sound studio is located in a low brick building, dim-lit and cool inside; its walls covered with album jackets. Pushing open a carpet-lined door I heard Bill Harrell singing a song I’d never heard before. I stood behind the console watching Bill McElroy flip switches and check levels. The music surrounded me like darkness does when the sunset dies. Fifteen-year-old John Harrell sat in a straight chair beside the barrier watching his father intently. “Do you remember all the good old stories you would tell to me?” Bill sang in his rich tenor voice. Mandolinist Eddie King sang harmony.

The lyrics held my attention; they told the story of a son reminiscing with his father about his childhood… of fishing in a mountain stream… of a mockingbird singing in a tree. When the song ended, Harrell opened the door and limped into the sound booth. His bad leg and twisted torso are the results of an old motoring accident. He knelt beside his son asking, “How did it sound?” “Fine —just fine,” John said smiling. Getting to his feet, Bill told me, “I wrote that song yesterday before I got out of bed.

John came into my room to say goodbye before going to school and I wouldn’t talk to him until I’d finished it.” At fifty-one, after three decades of playing bluegrass music, Harrell is in his most creative period.

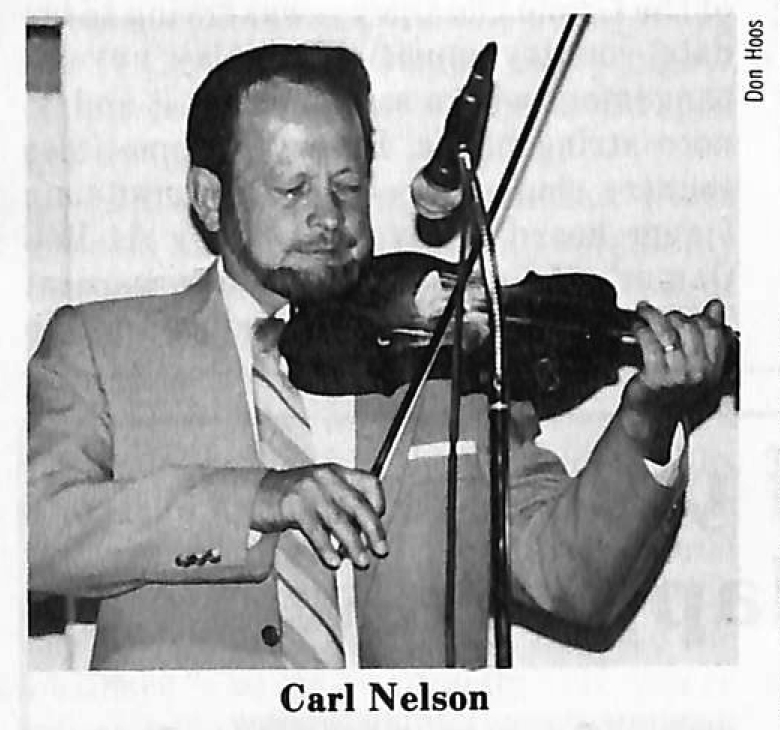

Bill’s always been a prolific songwriter. Now, he seems to be writing more songs than ever before. He records and performs more ballads than the uptempo tunes of a few years ago.” I get more requests for ballads and songs that I’ve written. Tunes like ‘Reno Bound’ and ‘Blue Ridge Mountain Boy’ will always be in our repertoire but the slow ballad suits my voice better,” he admits frankly. “I’m always trying to add a new dimension to the Bill Harrell and the Virginians’ show.” In search of a new dimension he’s begun to play fiddle. He and the late Buck Ryan played music together for sixteen years. Recently, he bought Buck’s fiddles from his widow. Carl Nelson, The Virginians’ premier fiddler, has been helping him out. Three fiddles are used on the groups’ rendition of “Faded Love.”

Eddie King, a native of Charlottesville, joined the Virginians when Larry Stevenson moved to the Bluegrass Cardinals in 1983. Drinking coffee from a styrofoam cup, King roamed the booth nervously, anxious to hear the first song he’d ever recorded with Harrell.

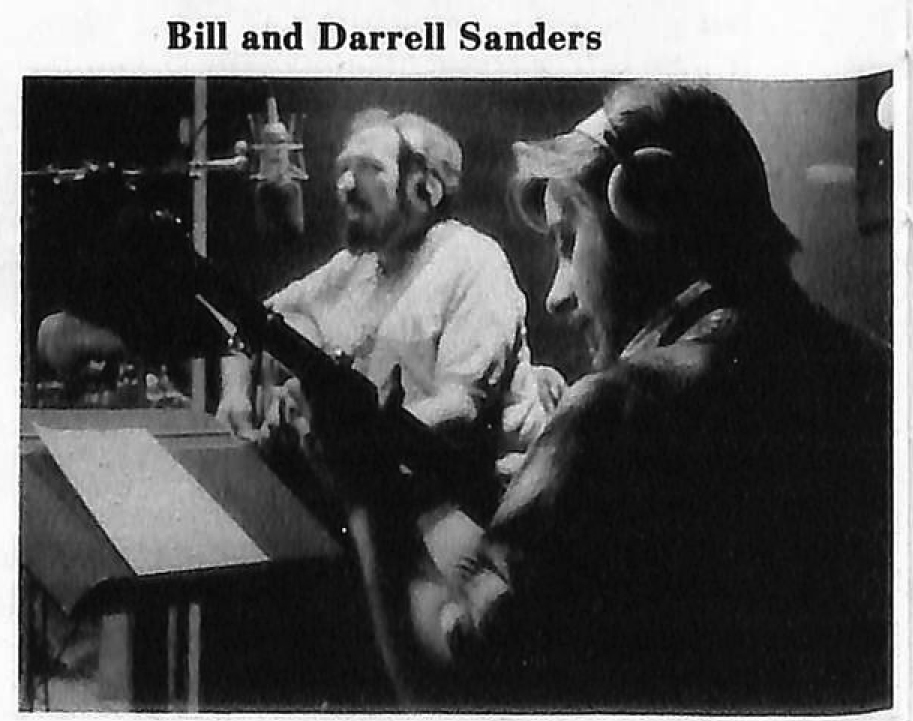

Darrell Sanders slouched in a padded chair listening critically to his banjo part. “I want to do that again,” he said softly. “I can do better.” Sanders is a careful musician. At 26, he’s the youngest member of the Virginians. “I’ve been with the group for seven years and seven months,” he informed me. “I wanted the job so bad I told Bill I’d play like anybody he wanted me to—Scruggs, Reno, Adcock—anybody. Just play like Darrell Sanders,” Harrell advised him. His album, “West Virginia Style”—a Webco release, attests to the fact that only Sanders sounds like Sanders.

Darrell returned to the studio, put on his headphones, picked up the banjo and recorded his part again. When McElroy played it back to him, he smiled. “Darrell’s been playing Dobro with us on stage,” Bill said. “He’s going to do a Dobro part on the next song.” Sander’s intensity is matched by fiddler Carl Nelson. Nelson’s virtuosity and musical know-how are acknowledged by his fellow bandsmen with both awe and good natured irreverence.

After Carl redid his fiddle part on the new song, Harrell commented—“I can’t tell a damn bit of difference.” Nelson added the second and third fiddle parts in rapid succession. “He’s the best,” Sanders declared. I agree with Darrell and had said the same to Carl Nelson. He’d shuffled his feet and stared at the floor. Nelson, once a Roanoke area farm boy, is painfully shy. He started playing fiddle at fifteen because his older brothers played guitar, mandolin and banjo. He first teamed up with Bill three decades ago. Nelson recorded with Bill Clifton, the Country Gentlemen and the Seldom Scene before rejoining Harrell in 1978.

Interviewing Carl Nelson is like getting blood out of a turnip. He could have been cast in the title role of the aged John Wayne movie, The Quiet Man. I admired his album “On Pine Lake,” another Webco release. When I asked him if he was going to record another album under his own name he said one word —“yes.” When I asked him when? He said—“soon.” Although Carl Nelson won’t blow his own horn there’s plenty of people in bluegrass music, who will sing his praises without much prompting.

WAMU disk-jockey Jerry Gray tells a story about Nelson that probably best illustrates Carl’s versatility. Years ago, Gray was working a job with a trio that required a fuller and bigger sound than the group could deliver. Jerry called Carl and asked him to bring his portable piano, along with his fiddle, to augment the trio. On one particular song, Nelson was seated at the keyboard when it came time for an instrumental break. He played the first half of the break on the piano, stood up and in the same motion, got to the nearest microphone in time to play the second half of the break on the fiddle without missing a beat. Gray expected Carl to play both the fiddle and the piano during the course of the evening, but he didn’t expect him to play them both at the same time. Many such stories surround Carl Nelson. Before he walks on stage, he paces nervously like a performer going before an audience for the first time. In the studio he’s all business—a man wrapped in harmonies—a study in total concentration.

Carl, Eddie and Darrell retreated behind the glass barrier to put a tag on Bill’s new song. A tag is a musicians word for an ending—sometimes a group concludes on the same chord, sometimes they fade away playing feverishly. “Carl makes that look so easy it’s disgusting,” a deep voice said behind me. Turning I saw bassist Ed Ferris, crammed into a plush chair. Ferris is bluegrass music’s Michelin man look-alike. In his hands a doghouse bass looks like a cello. He’s been playing bass with Harrell since 1973 when Bill was teamed with Don Reno. Before then, he played with Buzz Buzby, Cliff Waldron and the Country Gentlemen.

Ferris, who was born in Washington, D.C., spent his childhood and still lives in Hyattsville, Maryland. As a youngster, he studied and played bass instruments. “Yeah! at one time I played trumpet in the (Washington) Redskins’ Band,” Ferris laughed. He has a booming laugh that makes you laugh with him. In high school he played sousaphone, so when he started to play bass, he already understood the importance of the instrument and its function. “I was green, I didn’t know nothin’ when I started out. I had a lot of catchin’ up to do,” Ferris says modestly. He’s done the catching up he needed to do. In the past eleven years, Ed and Bill have performed in every state east of the Mississippi and a number of them west of the big daddy of rivers.

Ferris pulled himself slowly up out of the low chair. “I’m goin’ out in the lobby and take a nap on one of those sofas,” he said to nobody in particular. “You guys call me when you’re ready to do another number.” Bill Harrell sat on the floor writing a part for Eddie to sing on the next song. McElroy played back the tag that had just been recorded. “That’ll do,” Bill whispered.

Bill Harrell’s a soft spoken man who tries to give a personal touch to his live performances. When Bill and the Virginians play indoors, during the winter, he’ll try to beat the audience to the exits so he can shake hands with people as they leave. His manner is like that of a country preacher standing at the chapel door at the end of a Sunday service.

In truth, that’s only one side of his personality. I once saw him walk across a stage pushing a rubber-footed, wooden duck on a stick, while the Johnson Mountain Boys were trying to perform.

Harrell was born in Marion, a mountain town in southwestern Virginia. He remembers the first record he ever owned—“Precious Jewel” by the Delmore Brothers. He attended the University of Maryland in the 1950s, and had a radio show on Arlington, Virginia’s pioneer country music station—WARL. After meeting Jimmy Dean in Washington, he was a frequent guest on Dean’s CBS network TV show in New York. He and Don Reno toured together for ten years. When Reno died recently, I talked to Bill about his ex-partner. “I’ve lost a close personal friend, “he said sadly, “but music’s loss is greater than mine. Don was one of the best songwriters in the country.”

Bill Harrell thinks bluegrass music is treated like a poor relation by country music disc-jockeys and the Nashville establishment. “We don’t ever get a fair shake on the country music awards,” he says heatedly. “Why can’t bluegrass performers be put in a category by themselves? I’m tired of seeing the bluegrass award given to a country artist who crosses over into our music occasionally.”

The perennial battle between country DJs and bluegrass musicians is a topic Harrell never tires of discussing. “Reno & Harrell had an album of bluegrass hymns,” he told me, “that went unplayed on most stations. At that time, Ralph Emery of WSM—mother station of the Grand Ole Opry—was trying to update country music. He’d play any arrangement with a saxophone in it and ignore string music. Emery, a sometimes country singer, recorded the worst song I ever heard in my life—‘I Cry At Ball Games’. Me and George Jones were at WSM one day and he introduced me to Ralph. I asked him why he didn’t play hymns or bluegrass when he’d play a dog like ‘I Cry At Ball Games’ every night? Ralph asked George —‘Where did you get this smart kid?’”

Bill’s a tough mixture—like white gypsum and gravel. He has an unfailingly distinctive tenor voice, plays excellent guitar, is a talented songwriter and a hard-nosed businessman; He spends hours, every day he isn’t on the road, in a basement office in his Davidsonville, Maryland home corresponding with festival managers, club owners and anyone else who’s interested in engaging the Virginians. “I’ve always handled the business,” he says proudly. “If you’re gonna have a band you have to have jobs to play or you won’t have a band. It’s as simple as that.” I asked him if the pressure of booking the group was ever too much. “No,” he replied. “I get irritable when I call a lot of people and have just missed several dates and I get frustrated when I get four or five offers and can only take two.”

In the forever twilight of the recording studio, I watched Bill Harrell. He’d finished writing words for Eddie King. He was staring into the gloom listening intently to something only he could hear. Bill is a widower. His wife Ellen died four years ago. Since then, his family and his music have filled his life—taking every moment of his time. It’s the way he wants it. “Go wake up Ed,” he told his son. “I scribbled this song on the back of an envelope late one night,” he said, “riding home on the bus.”

Ed Ferris came in yawning and followed Bill, Carl, Darrell and Eddie behind the glass partition. Bill McElroy, once again, flipped switches and checked sound levels. Finally, he waved his hand at Bill and the Virginians. “I love the springtime that’s when I met you,” Bill Harrell sang. I was lost in the song. It was about an older man’s love for a younger woman or a musician’s love for music. Music is a mistress that’s always young. “So I’ll go on walking down life’s road to winter,” he sang, “and hold to the springtime, it’s the season for me.”

*Note: The album Bill Harrell & the Virginians were recording when the authors interviewed them is “Do You Remember,” a current Rebel release.