Home > Articles > Special Series > Bill Emerson with Jimmy Martin (1961-1966)

Bill Emerson with Jimmy Martin (1961-1966)

At the end of the last installment of this series, Bill Emerson was working with Red Allen and Frank Wakefield. Regarding that experience, in an interview conducted by Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine in 1992, Bill said, “Red Allen and Frank Wakefield came to town and were looking for a banjo player. We did a lot of local clubs and recorded ‘Little Birdie’ and some other tunes that came out on 45s. Red and I were associated for a number of years. He was fresh from leaving the Osborne Brothers and had a lot of professionalism. Once we played a nightclub and I was complaining that I couldn’t get anything right on the banjo. He said, ‘You know, Bill, you’re playing too loud.’ I went back the next set and eased up and didn’t have a problem at all. Those are the kind of things that Red could tell you. I’ll always consider him to be one of the greatest bluegrass lead singers.”

Jimmy Martin—Round One

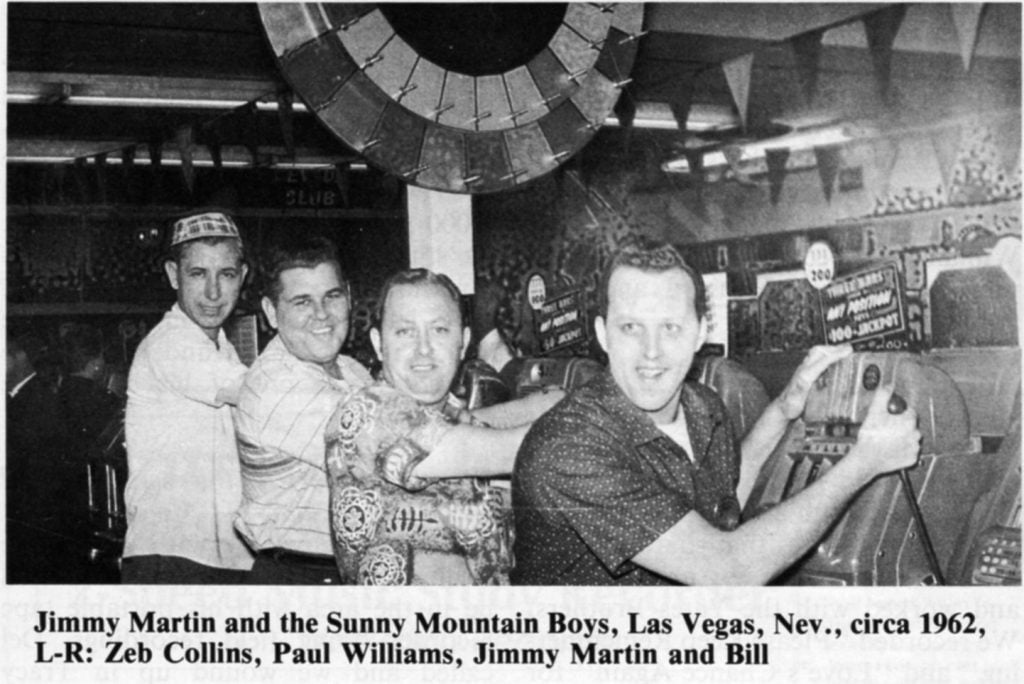

Emerson worked with Red Allen and Frank Wakefield until he got a call from Jimmy Martin. Written sources have put this date sometime in 1961 or 1962. Hand-written notes about Bill’s career that were put together by Bill’s wife, Lola, indicated that it was late in 1961. Paul Craft had been working as Jimmy’s banjo player after J.D. Crowe left the band. When Craft came down with the mumps, Jimmy gave Emerson a call. The first show was in East Patterson, New Jersey with Paul Williams (mandolin) and Zeb Collins (bass and comedy) also in the band. In an interview conducted for the Bluegrass Music and Hall of Fame’s Oral Histories Project, Emerson recalls a teenager named David Grisman being in the audience that night. After that show, Martin told Emerson, “I like your playing, I like your attitude. If you want the job, I’ll hire you.” About a month after this show in New Jersey, Martin helped Emerson load his belongings into a U-Haul trailer that he pulled behind his Cadillac and Emerson moved from Washington, D. C. to Wheeling, West Virginia.

In the 1992 Bluegrass Unlimited interview, Bill remembered, “Paul got the mumps and they had a job in Patterson, N.J. Jimmy called and said, ‘I need you to work with me.’ I met him on the Pennsylvania Turnpike and we went to a motel room and ran through the tunes for his show. I already knew most of his stuff because I had been thinking about the possibility of working for him. Afterwards, he said Paul Craft was planning to leave and offered me a job. I accepted and stayed with Jimmy about five years all together. It was a lot of fun and that was my education right there. Just about everything I’ve used down through the years I learned from Jimmy. He’s a master and right off the bat I could see the value of what I was getting from him.”

In a two-part article that Bill Emerson wrote for Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine in 1968 (October and November issues) titled “On The Road With Jimmy Martin,” Bill said, “I had already played for years with such groups as Red Allen, Buzz Busby, Bill Harrell, The Stoneman Family, The Yates Brothers and the Country Gentlemen, but I learned more in my two years on the road with Martin than I did in all the rest of the time put together.”

In the Bluegrass Oral Histories interview, Emerson said, “Jimmy Martin was one of my favorites of all the bluegrass first generation guys. I liked his songs and I could play them and so it was natural for me to step into his band, and that is what I did…His music had this freedom to it and this drive to it and I just loved his music. To be able to stand with him on stage and play stuff that I had listened to and that I had sat there and played over and over and just loved was a real thrill.”

When questioned about specific things that he learned from Jimmy Martin— who called Emerson “Big E”—Bill said, “Well, Jimmy wanted you to fit with what he was doing. He never said to me, ‘I want you to play it like J.D.’ But, he would say things like, ‘Instead of hitting just one string I want you to reach down and grab a whole handful to make it sound full. Keep the tone of that banjo in there all the time.’ He showed me how to keep my banjo pointed at the microphone and how to work in and out. Jimmy didn’t play the banjo himself, but he could two-finger it just enough to show you what he wanted. You know, Earl Scruggs said the most important thing to him is how he gets in and out of a break. Jimmy taught me that was very important. Jimmy would say, ‘Hit those pick-up notes just like a fiddle would and keep them separated. You don’t want one string loud and the next not loud enough.’ He showed me how to put the emphasis, rhythm and dynamics into my playing and singing. He also taught me about show business in general. There wasn’t any part of it that Jimmy didn’t instruct me on.”

In Emeron’s 1968 BU article, he said, “Jimmy eats, sleeps, lives and breathes bluegrass music and he talked it to me in a steady stream. He can’t actually play a banjo, but he can fake it through with two fingers enough to show you what he wants. In a couple of weeks he had me playing stuff I hadn’t even thought about before.”

In the Bluegrass Oral Histories interview, Emerson gave more specifics. He said, “His philosophy about fiddle music was that when you get into something, you do it the way the fiddle would do it. If you are playing ‘You Don’t Know My Mind,’ you want those staccato notes…dit-dit-dit. How to bring it out, how the dynamics work, how you work a stage, how you want to appear to the audience, how you work the microphone, things like that. Everything about the business…the business was Jimmy’s life. Everything that he knew about the business, I tried to learn too. It helped me launch a career later on as a band leader. It was the experience of a lifetime.”

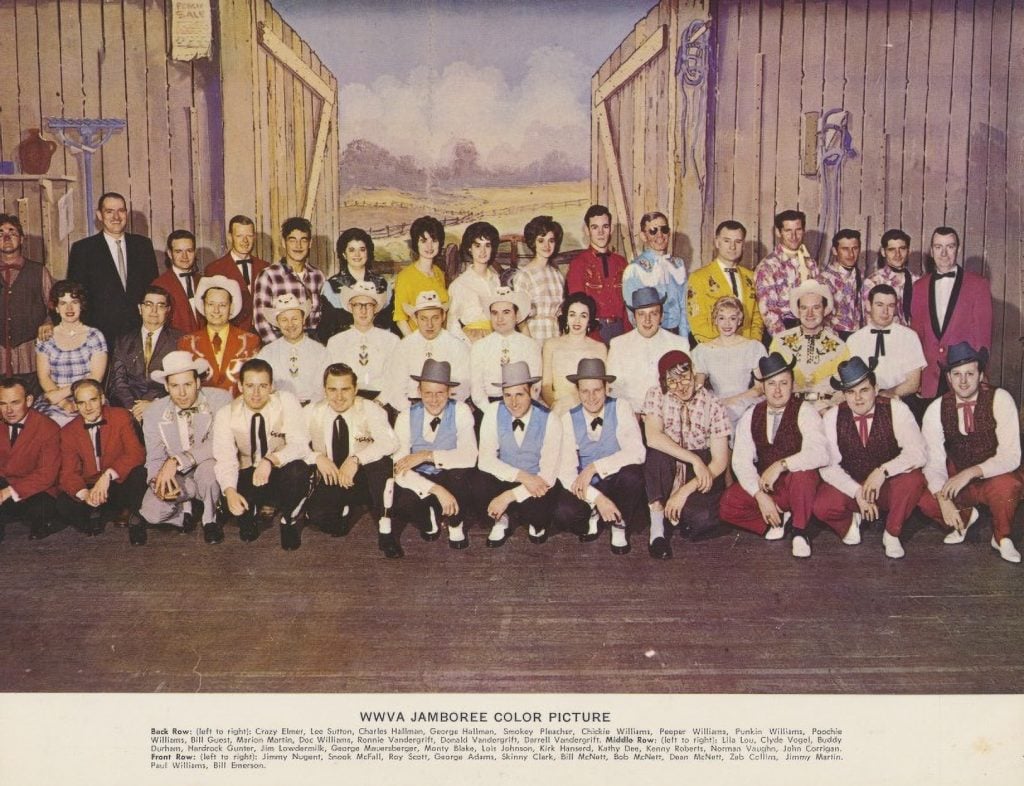

Bill worked with Jimmy Martin from late in 1961 through early 1966. During that time period he left Martin in December, 1962, but returned late in 1964. In 1962 Emerson had been performing with Martin at the WWVA Jamboree in Wheeling, West Virginia and living across the river in Martin’s Ferry, Ohio. Martin wanted to move to Nashville, but Emerson did not want to go there, so he left the band and returned to Washington.

Back To Washington, D.C.—then Martin Round Two

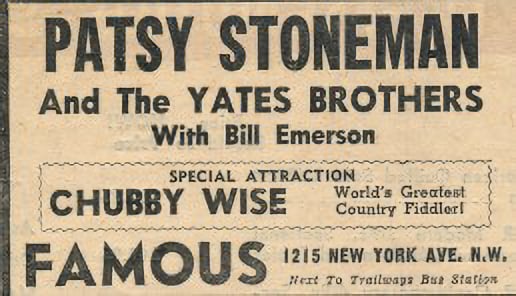

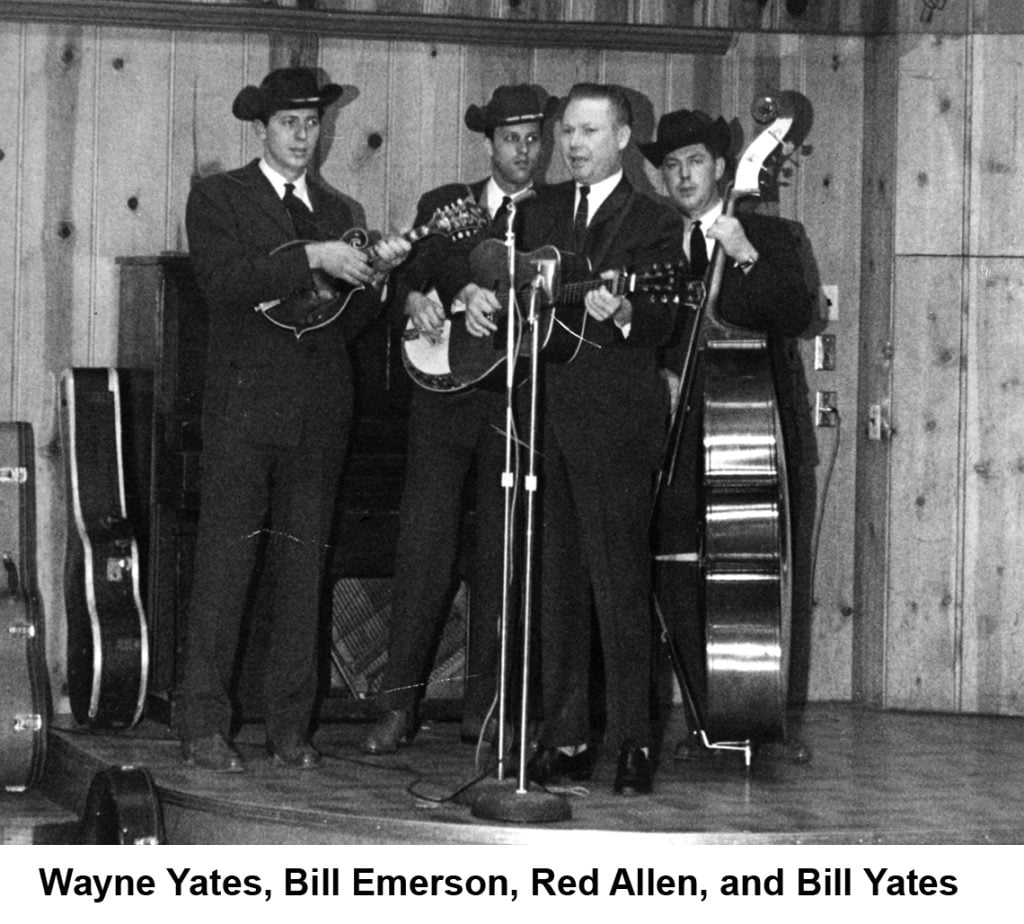

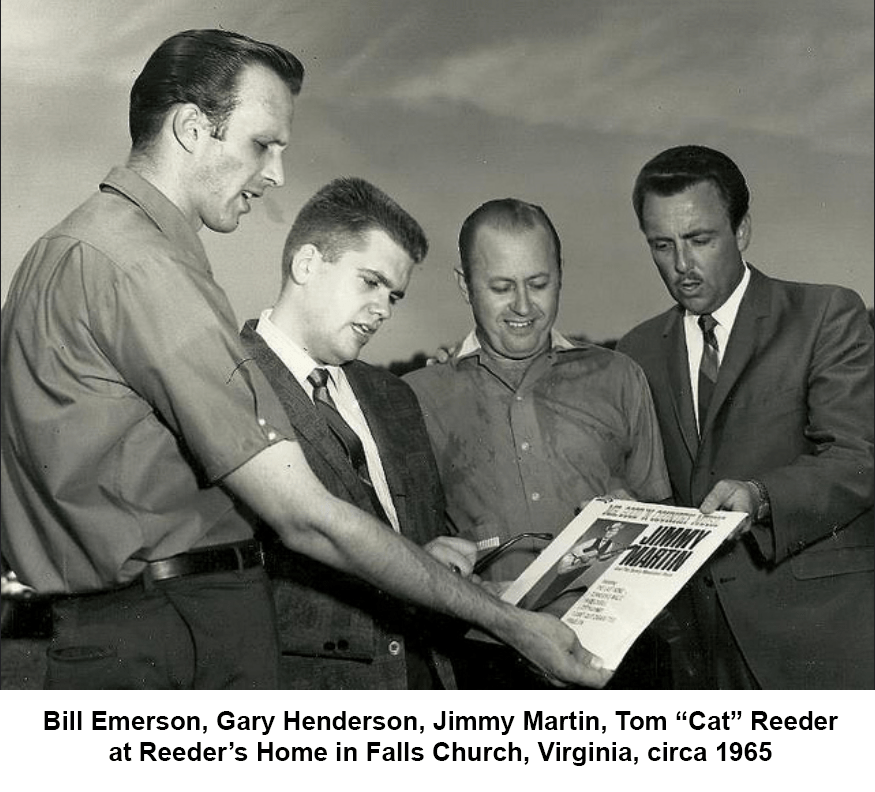

Upon his return to the D.C. area, Emerson started performing with the Yates brothers and Ferrell Brown. They worked at WKCW, Warrenton, Virginia and made two semi-commercial sides (“Love’s Chance Again” and “Please Keep Remembering”) for DJ Tom “Cat” Reeder’s KA$H label. When Brown left the group, Red Allen took his place and the group became The Kentuckians. They recorded for Pete Kuykendall’s Glenmar label, but Kuykendall didn’t release the recordings. He gave them to Dick Spottswood for his Melodeon label.

Late in 1964 Emerson went back with Jimmy Martin, taking Bill Yates with him on bass. Others working with Martin at the time were Vernon Derrick (fiddle) and Bill Torbert (mandolin). During his time with Jimmy Martin the band performed as guests at the Grand Ole Opry and the Louisiana Hayride and as regular members of the WWVA Jamboree in Wheeling, West Virginia. The band also performed for a week at the Golden Nugget in Las Vegas and at a USO show for the troops in Newfoundland. Bill Emerson was also in Jimmy Martin’s band when Carlton Haney produced the very first multi-day bluegrass festival at Cantrell’s horse farm in Fincastle, Virginia on Labor Day Weekend in 1965. He was one of the judges of the banjo contest that weekend, along with Ralph Stanley and Lamar Grier. In the 1992 BU interview Bill added, “We also played in every country music park and nook and cranny that Jimmy could get us into.”

On The Road with Jimmy Martin

Traveling with Martin on the road was not easy. There were no buses, and often no hotel rooms, or restaurants. They traveled and slept in Jimmy’s 1959 four-door Cadillac Fleetwood—the bass lashed to the top and the instruments and bags in the trunk, hats on the back ledge, and five or six people packed into the car. When they slept, they slept in the car executing what Jimmy called “sleepin’ on heads,” where one person’s head was on another’s shoulder and that person’s head rested on the first person’s head. Before a show they would stop at a gas station to shave and clean up. Emerson has said, “I remember going three days one time without taking off my shoes.”

When the band ate, the method was what Martin called “jungleing.” In the 1992 BU article, Emerson explained, “Instead of stopping at restaurants to eat, we jungled. That’s bologna, cheese, bread, mayonnaise, mustard, tomatoes and those little paper salt and pepper shakers you buy. We’d find a picnic table somewhere by the side of the road and have a great time. You know, we’d play Friday and Saturday nights at the Jamboree, go upstairs to the WWVA studios and broadcast a live show. By the time that was over, it was about 11:30 p.m. We’d load the car and away we’d go. We wouldn’t get back to Wheeling until the next Friday. We travelled all over the country like that all year long.” Bill recalls the band working on the road 220-225 days per year. The remaining time saw the band recording, rehearsing, or playing the Wheeling Jamboree.

In the Bluegrass Oral Histories interview, the interviewer asks Emerson how he tolerated the hard traveling. Emerson said, “What made it tolerable is that when you got to where you were going and you put on your hat and your coat, got your banjo out and tuned it up, you went out there and got to play the banjo with Jimmy Martin. That is what made it tolerable. When you went to Nashville and recorded ‘Sweet Dixie’ and ‘Theme Time’…and all of those great songs with Jimmy Martin. I was doing my art. That is what I wanted to do. There is a certain degree of immortality in that. You do those things, and they are there forever. They never go away. I felt driven to travel and be with Jimmy Martin and to be a part of his band.”

To learn more about Bill Emerson’s life on the road with Jimmy Martin, please read a few of the articles that appeared in Bluegrass Unlimited over the years that now reside in the Archives section of our website. Since this information is easily accessed online, there is no reason to reproduce it in this article.

These articles can be found at the following URLs:

https://www.bluegrassunlimited.com/article/on-the-road-with-jimmy-martin-part-i/

https://www.bluegrassunlimited.com/article/bill-emerson/

https://www.bluegrassunlimited.com/article/bill-emerson-banjo-player-extraordinaire/

Recordings 1962-1966

The first time that Bill Emerson recorded with Jimmy Martin was on August 29, 1962 at the Columbia Recording Studio in Nashville. The band was recording a gospel album and Owen Bradley produced the sessions. The band recorded “Lord I’m Coming Home,” “Goodbye,” “Pray the Clouds Away,” “Give Me the Roses Now,” and “Prayer Bells of Heaven,” with Emerson on banjo, Jimmy Martin on guitar, Paul Williams on mandolin, and Joe Zinkan on bass. Martin sang lead, Kirk Hansard sang bass and Lois Johnson sang high baritone.

The next day, the band went back into the studio and recorded “Give Me Your Hand,” “Stormy Waters,” “What Would You Give in Exchange,” “Shut-In’s Prayer,” “A Beautiful Life,” and “Little White Church.” The songs from these two sessions were released on the album This World Is Not My Home. On the next day, August, 31st the band recorded “The Old Man’s Drunk Again,” “Moonshine Hollow,” “Hey Lonesome,” and “Tennessee.”

In January of 1963, after Emerson had left Martin’s band the first time, he went into Pete Kuykendall’s Glenmar recording studio and recorded with Ferril Brown, Wayne Yates and Bill Yates. In an email to his son Mike, Emerson had this to say regarding these sessions, “I believe Ferril Brown was on guitar. Pete Kuykendall was the engineer, but not the producer. If credit goes to anyone it should be Bill Yates. I recollect the recordings were done in Kuykendall’s basement. KA$H Records was owned by Tom Reeder. Bill Yates sang tenor on both songs. Wayne Yates sang lead and I sang baritone.”

The first song that the group recorded on this date were “Please Keep Remembering,” which was written by Bill Harrell and included Rudy Gabriletto on pedal steel guitar with Emerson singing baritone, Wayne Yates singing lead, and Bill Yates singing tenor. The second song was “Love’s Chance Again,” which was written by Bill’s wife Lola Emerson.

The next recording that Emerson was involved in occurred in May of 1963 in Ben Adelman’s studio in Takoma Park, Maryland. This session was for a project titled Tom Morgan: Bluegrass with Family and Friends. The session included Emerson (banjo), Red Allen (guitar), Frank Wakefield (mandolin), Rick Morgan (bass), Carl Nelson (fiddle), and Kenny Haddock (Dobro) with Emerson singing baritone, Tom Morgan singing lead, Red Allen singing tenor, and Frank Wakefield singing baritone.

This album was not actually released until 1983. In the liner notes, Tom Morgan writes, “Side 1 was conceived as one side of a joint album to be shared with Bill Emerson, and the session was recorded without bass (to be dubbed in later) so I could concentrate on the vocals at hand. Although the original idea of a shared album never materialized, the master tape remained in storage with several students of the art who were aware of its existence lobbying for its eventual release.” The songs that were recorded for this project included “I Wonder If You Feel The Way I Do,” “Red Wings,” “Old Country Church,” “Pig In The Pen,” “Take Me Back To Happy Valley,” and “Back Up And Push.”

Emerson’s next recording sessions occurred in October of 1963 when he went back into Pete Kuykendall’s studio with Red Allen and Frank Wakefield. The musicians included Emerson (banjo), Red Allen (guitar), Frank Wakefield (mandolin), Tom Morgan (bass), and Billy Baker (fiddle). The group recorded “Little Birdie,” and “Faded Memory.”

In the liner notes to Rebel’s release of Red Allen: Keep On Going Rebel and Melodeon Recordings, Jon Hartley Fox wrote, “The demo must have worked [Four songs were recorded at Pete Kuykendall’s studio in Falls Church, Virginia with the hope of trying to get a recording contract with Rebel Records], as the band returned to Wynwood Studio a few months later; on Wednesday, October 2, 1963, to record a 45 for Rebel Records. Banjo player Ronnie Robinson had returned to Columbus, Ohio and had been replaced by Bill Emerson, a highly gifted banjo player who would become esteemed for his work with this band, Jimmy Martin, and the Country Gentlemen and others. The band recorded two songs, the traditional ‘Little Birdie’ with Red on lead vocal and ‘Faded Memory,’ an original song credited to Red and Frank that featured Frank on lead vocal.”

In January of 1965, Emerson went back into Pete Kuykendall’s studio to record with The Kentuckians—Emerson (banjo and baritone vocals), Red Allen (guitar and lead or tenor vocals), Wayne Yates (mandolin and lead of baritone vocals), Chubby Wise (fiddle) and Bill Yates (bass and tenor vocals) or Pete Kuykendall (bass). They recorded “Hello City Limits,” “Flowers By My Graveside,” “Froggy Went A Courtin,” “Sad And Lonesome Day,” “Journey’s End,” “Those Gone And Left Me Blues,” “No Blind Ones There,” “The Family Who Prays,” “Worry My Life Away,” “Down Where The River Bends,” “Out On The Ocean,” “I Don’t Know Why,” and “If That’s The Way You Feel.” Regarding having the opportunity to work with Chubby Wise, Emerson said, “Chubby Wise was an all-time great first-generation pioneer. [I loved] to see him wag his head when he played.”

After rejoining Jimmy Martin, Emerson went back into the Columbia Recording studio in Nashville to record five instrumental tunes with Martin in July of 1965. The musicians on these sessions included Emerson (banjo), Jimmy Martin (guitar and lead vocals), Earl Taylor (mandolin and harmonica), Vernon Derrick (fiddle), Floyd Lightnin’ Chance (bass), and William “Willie” Ackerman (drums). The songs that were recorded were: “The Last Song,” “Sweet Dixie,” “Wild Indian,” “Run Boy Run,” “Theme Time,” and “Orange Blossom Special.”

The song “Sweet Dixie” was a tune that Emerson had written and brought into the band. Jimmy Martin made some suggestions regarding the tune and thus what Emerson recorded with Martin was a bit different than the original tune that he had written. In the Bluegrass Oral Histories project interview, Emerson said, “When I came to Jimmy, I had a different version of that. Jimmy gave me the idea for the pull-off in the second part. He said, ‘That string-flipping thing that you are doing there. Keep going on that.’ Jimmy would get right down on the floor on his knees, ‘Do this, do that. That’s good. Keep doing that.’ That is how he collaborated on that. It was my tune to start with, but Jimmy had a big part in how that developed and finally came out.”

In September of 1965, Emerson was once again in the studio with Jimmy Martin. The musicians on these sessions where Emerson (banjo), Jimmy Martin (guitar and lead vocal), Bill Torbert (mandolin), Bill Yates (bass). The songs recorded were “Poor Ellen Smith,” and “Shenandoah Waltz.” In December of 1965, Emerson and Martin went back in the studio with Bill Torbert (mandolin), Floyd Lightnin’ Chance (bass), Vernon Derrick (fiddle), and William “Willie” Acerman (drums) to record “I Can’t Quit Cigarettes,” “Lost Highway,” and “The Good Things Outweigh The Bad.” Another recording session with this group occurred in January of 1966. They recorded “The Summer’s Come And Gone” (with Emerson singing tenor, Martin lead and Derrick high baritone), “Fraulein,” “You’re Gonna Change,” “Tennessee Waltz,” and “Little Maggie, She’s So Sweet.”

Playing Jimmy Martin’s Music

While many bluegrass band leaders will allow their musicians a lot of freedom in their playing. Jimmy Martin was known as someone who wanted members of his band to play his music his way. Some musicians who played with Martin felt as if he was too demanding and didn’t stay long. In the 1968 BU article, Emerson’s addressed this issue, “Jimmy wanted his musicians to play his stuff. He didn’t figure he needed a banjo player that played like Earl, Ralph or Don, or a mandolin player who tried to copy Bill Monroe or Jesse McReynolds. He just wanted a man to play the songs the way he was singing them. That is certainly his right as an employer.”

Emerson also addressed this topic in the Bluegrass Oral Histories project, saying, “When you work with Jimmy Martin, it wasn’t free form. You played his music the way he wanted it. If I’d take off playing a different version of ‘You Don’t Know My Mind,’ than what was on the record, I was told right off the bat, ‘That ain’t the way it goes, I don’t want it played like that. You are playing my music, you play it the way I want it played.’ Even to the point to where if you were interested in Flatt & Scruggs and you saddled over there to talk to some of the Flatt & Scruggs band members, Jimmy didn’t like that at all. He’d say, ‘You are over there playing ‘Foggy Mountain Breakdown’ and stuff like that. I’m the guy who is paying you. You ought to be over here in the corner practicing my stuff.’ He had a good point there.

“You had to play his music the way he wanted it and if he heard you doing something on stage that he didn’t like, he had no problem turning around and giving you a look. You knew right then, ‘Hey, I’m doing something wrong here. I better straighten up.’ He wanted all your back up, all your singing, all your movements to be exactly what he’d know would happen and the way he wanted it. That is the way we rehearsed it.”

Leaving Martin Again

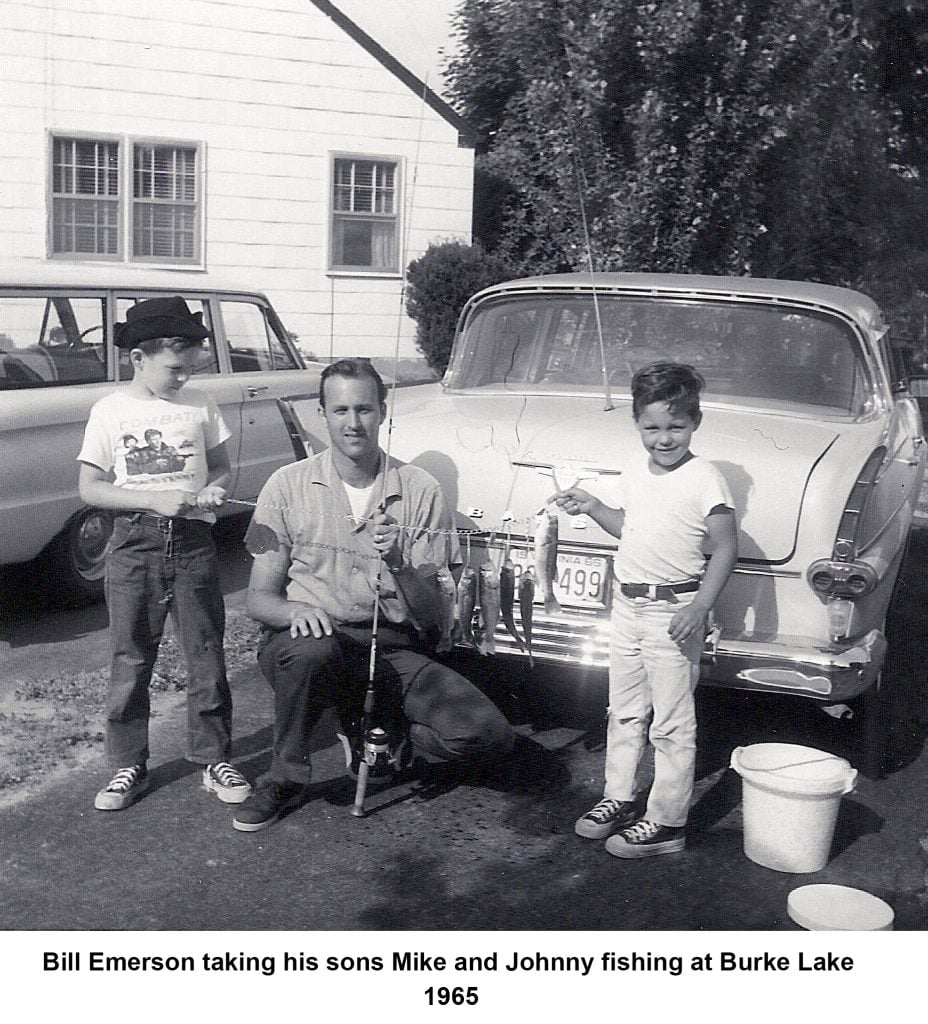

Bill Emerson left Jimmy Martin’s band in 1966 due to the overwhelming amount of tasks that he had with the band, including—running the show, collecting the money, selling the merchandise, loading and maintaining the car, and teaching the new band members their parts. Jimmy was also going through a divorce at this time, which didn’t help matters. Additionally, Emerson was living in Washington, D.C. during this time with a wife and two young kids. He was driving back and forth to the gigs and after one show at the Frontier Ranch in Columbus, Ohio he fell asleep at the wheel. Luckily, the car ran down a grassy center strip and came to a stop when the front wheel dropped into a concrete drain. That was the final straw. Emerson left Martin’s band so that he didn’t have to push himself so hard on the road and could stay close to home with his family.

For those readers who are interested in how Bill Emerson summed up his time spent with Jimmy Martin, he said it best at the end of his 1968 two-part article in Bluegrass Unlimited. You can read what he wrote here:

https://www.bluegrassunlimited.com/article/on-the-road-with-jimmy-martin-part-i/

In addition to working as a musician during the years 1961 to 1966, Bill also had a few other odd jobs to help him make ends meet. In 1963 he worked at a auto part driver for Arlington Rambler in Arlington, Virginia. In 1964 he worked as a septic tank serviceman for Ashley’s Odorless in Alexandria, Virginia. In 1965 he was a house painter for Brown & Church Painters and in 1966 he was a sign painter for Kisley Signs in Falls Church, Virginia.

In an email to his son, Mike, Bill Emerson explained the house painting job. Bill said, “We mostly did inside work. . .no need to scrape and sand old peeling paint, and no 60-foot ladders to fool with. Ferrell Brown was previously employed as a painter at the White House after which he went into business for himself. He managed to get some apartment projects to paint. He’d paint them when the occupants moved out and before the new ones moved in. Sometimes he’d paint them while the people were still living in them. Bill Yates worked for him and through him I became employed to paint apartments.

“Porter Church also had a painting business. Ferrell Brown was in business with Porter Church’s brother Jim Church. Jim lived in Annandale and was a talented claw hammer banjo player. I also worked for him for a year or two. Ferrell also did custom painting in expensive homes. He was very talented. The attraction was that the money was good, there was no time clock to punch and you had no one hanging over your shoulder. Ferrell supplied the paint and equipment and paid us for what we painted. $80.00 for a two BDR apartment plus $6.00 for the kitchen, $4.00 for the bathroom. One man would roll and the other would cut in. We could paint 4 apartments in one day and make 180.00 each. A no stress job and not bad money back then.”

The next article in this series will cover Bill Emerson’s career from the time he left Jimmy Martin, early in 1966, through the time he rejoined the Country Gentlemen in 1969.

Share this article

4 Comments

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

One thing that seems to be left out in this time period is the impact of the Arlington Music Store on Lee Highway. I learned a lot by spending time there in the mid-60s. Bluegrass folks I remember meeting there included John Duffey (repair man), Charlie Waller (guitar lessons), Bill Emerson (banjo Lessons).

This is so amazing. I didn’t know Bill had all those sideline jobs. I knew he did work on the side, but never knew what those jobs were. Further, my connection with Bill goes deep. I played banjo with his former band mate, Wayne Yates in Wayne Yates and Company. I also lived near Ferrell Brown and picked with him often. And, in 1992, Charlie Waller offered me a job playing banjo with the Country Gentlemen, which I declined because of my day job. Bill’s and my careers wove in and out for years. Eventually I got to play guitar with him at a Sweet Dixie Band gig. Learning about his background is so interesting. I knew some of it, but not a lot! Thanks!!

This is a fascinating look at the evolution of bluegrass through the eyes of one of the greats, Bill Emerson.

I liked the article very much except there were a couple of errors. Jimmy Martin appeared at the Golden Nugget, Goose Bay, Labrador, and Thule, Greenland before we moved to Nashville in March 1963. Also, Jimmy never booked any shows. I was the one who got him into all the “nooks and crannies”. I booked all the shows for Jimmy Martin beginning in 1958, my first attempt at booking. I continued to book Jimmy after we moved to Wheeling in 1960 to September, 1966. I booked the first bluegrass festival for Jimmy with Carlton Haney at Fincastle. I even booked some shows for him in 1967.