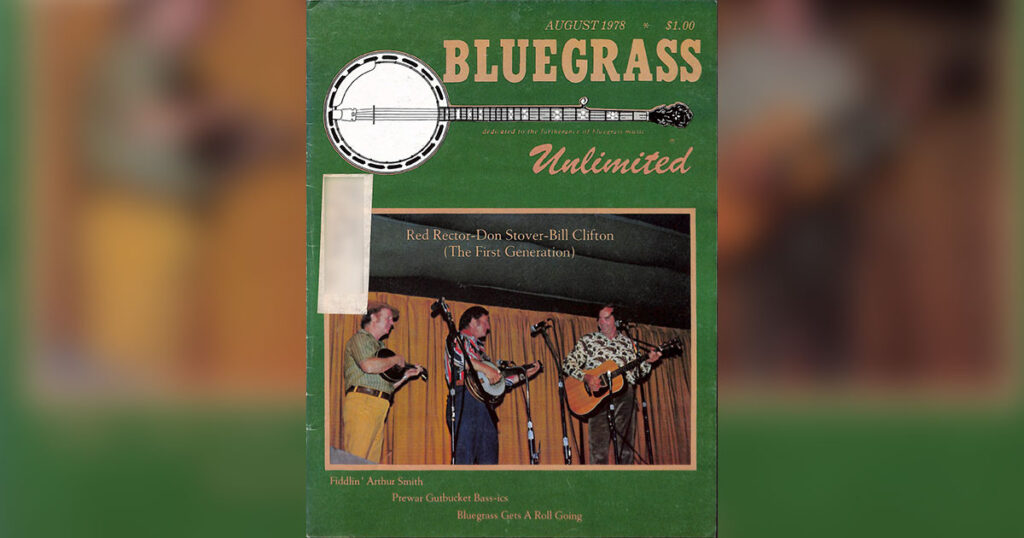

Home > Articles > The Archives > Bill Clifton—Red Rector—Don Stover: The First Generation, A Bluegrass Experiment

Bill Clifton—Red Rector—Don Stover: The First Generation, A Bluegrass Experiment

By Dick Spottswood

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

August 1978, Volume 13, Number 2

Over thirty years ago an astute jazz promoter named Norman Granz had an idea. Big bands had dominated the jazz and pop scenes before World War II, producing much of the significant talent which emerged during the era. But between the war itself and the spiraling inflation which followed it there was little opportunity for new bands to succeed and even most of the established ones were going under. Granz noted that a number of top-flight jazz soloists were either out of work or scuffling hard for the few jobs available. So he conceived an all-star system which he called “Jazz at the Philharmonic,” assembling the reigning names of the era into package shows which toured America and Europe, featuring names like Lester Young, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Billie Holiday and many others who consistently served as drawing cards for his financially successful ventures. And it was a formula which kept him and his musician colleagues solvent until the advent of rock and roll in the mid-50’s, which managed to duplicate the excitement Granz’s tours had provided while presenting a simplified lowest common denominator music which 10- and 12-year olds could relate to.

What, you may well ask, has Norman Granz to do with anything a bluegrass fan might want to read about? Well, several things. The years of Jazz at the Philharmonic’s ascendancy also marked the first years of bluegrass development, and along some of the same lines. Bluegrass has succeeded because its best musicians have been as uncompromising in their artistic vision as were Lester Young and Charlie Parker in jazz. Much of the early and continuing excitement in bluegrass has, like jazz, been due to the competing and contrasting voices of individual performers, the best of whom have risen to recognition because they have had unique and indispensable elements to add to their music.

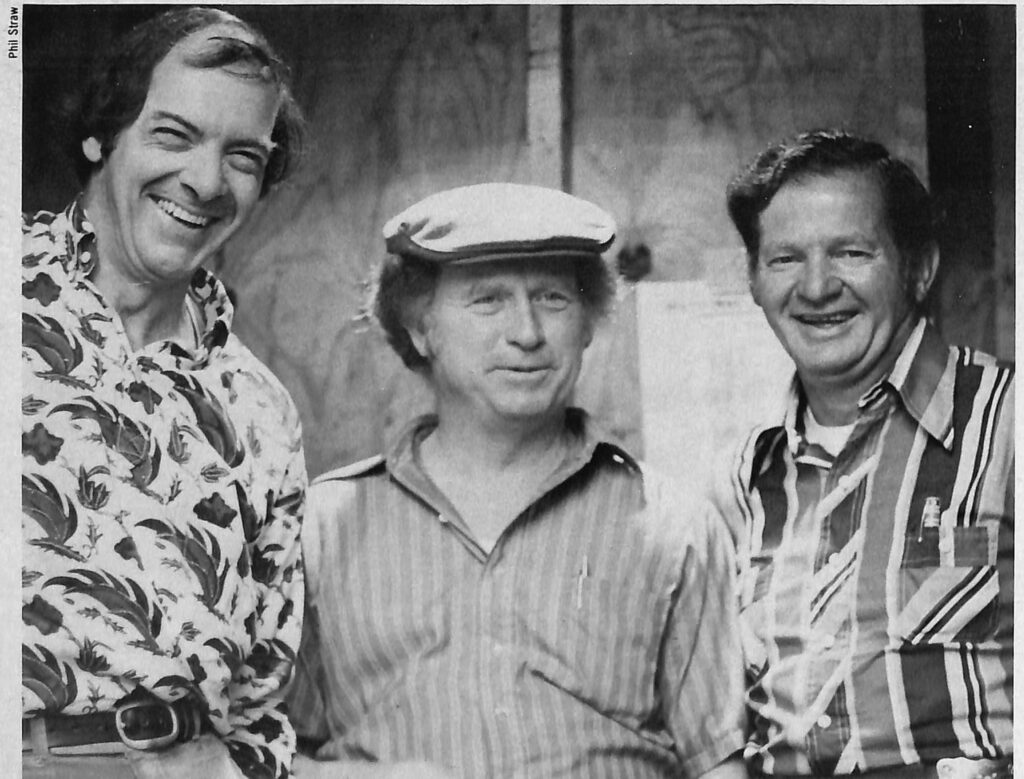

This story deals with three of the best of them-Bill Clifton, Red Rector and Don Stover, and The First Generation, which is what they aptly style their new group effort and a renewed commitment to each other and their music. This particular association marks the first time bluegrass has seen a new group formed from established performers. The pattern thus far has been the development of new talent within established bands, particularly those of Bill Monroe, Jimmy Martin, the Stanleys and others who have made a point of hiring and tutoring unknowns whose talents merit exposure. The best of this talent has graduated and gone on to form new ensembles and repeated the process anew.

The First Generation. The name has been chosen to describe its members and call attention to their presence during the formative years of bluegrass. Though Don, Red and Bill each come from different parts of the South and were never associated professionally in those days, each was a noted musician by the early 1950s and has gone through both good and lean years since then. And all three have established reputations placing them in the forefront of their art.

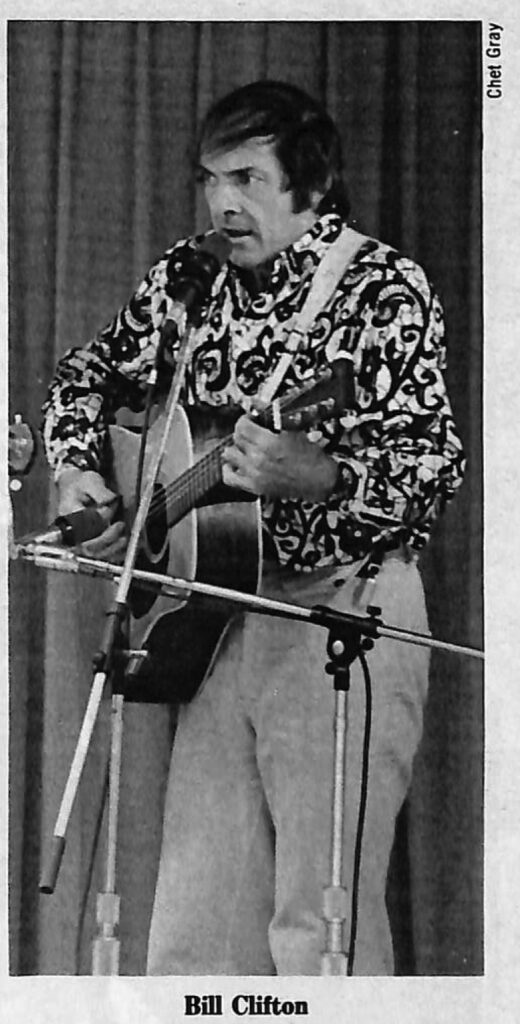

Bill Clifton was born in 1931 into an affluent Maryland family. His first instrument was an accordion, but it was quickly abandoned as he discovered a taste for country music. An older sister listened faithfully to the Wheeling (West Virginia) Jamboree over WWVA each Saturday night, and soon Bill had acquired a guitar and began to learn songs from both radio and records. As his repertory increased, he found opportunities to play informally at local dances. His first semiprofessional opportunity came when he enrolled at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Virginia in 1948 and took a job as soloist from 6 to 7 A.M. on a local station, WINA. On these occasions he was frequently joined by Paul Clayton, another undergraduate who subsequently established himself as a favorite in folk- revival circles. Bill’s radio work expanded to include activity in Richmond and Baltimore and finally, in 1952, the formation of a working band, the Dixie Mountain Boys. At first there were three members; Bill, banjo player Johnny Clark and fiddler Winnie Sisk; the latter was soon replaced by Bill Wiltshire. Their travels took them from Charlottesville to the WWVA Jamboree, Kingsport and Knoxville in Tennessee, and further into Georgia, looking for steady radio work. None materialized in spite of determined efforts and the band broke up in the winter of 1953. Bill went back to Charlottesville to finish up his degree and then enlisted in the Marines. By this time, some 1953 material Bill had made for Blue Ridge was released. One song, “Flower Blooming in the Wildwood,” attracted notice and called attention to the special qualities this young man with a solid baritone voice could lend to old-time songs. By the time of his release from the Marines, Bill took Ralph Stanley’s advice and auditioned successfully for Mercury Records. The association with Mercury lasted until Don Pierce who was producing most of their country records parted from the company. Bill followed Pierce to Starday and recorded some of his best music for the company over the next few years. Because he rarely had a working band, Bill was able to make use of some top musicians for his recording sessions: John Duffey, Mike Seeger, Ralph Stanley, George Shuffler, Charlie Waller, Tommy Jackson and others all helped out on Bill Clifton records in the late 1950s and early 1960s. During this period his activities began to take an even wider scope. Bill became a broker, buying and reselling radio and tv stations, served on the board of directors at the Newport Folk Festival, and even launched the first bluegrass festival—a single day event—on record, in Luray, Virginia in 1961.

Following these activities he went overseas to live in England, and served for two years with the Peace Corps in the Phillipines. Since then his home has been in England, and he has played a major role in introducing and performing bluegrass around the world.

In 1972 Bill and Red Rector met for the first time at Bluegrass Unlimited’s Indian Springs Festival. They played informally on stage and liked what they did together. Since then the two have recorded together and Red has been an indispensable part of Bill’s frequent European tours.

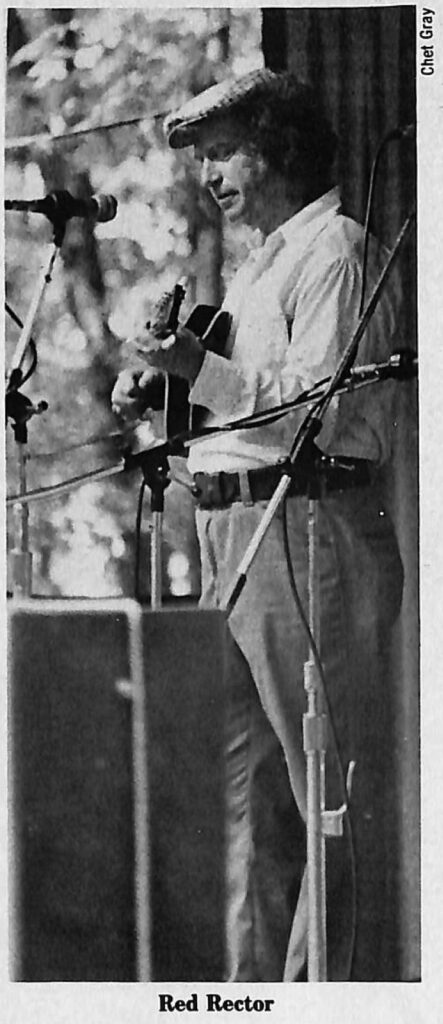

William Eugene Rector has long been recognized as one of the mandolin’s leading original stylists. He has been playing his instrument professionally since his early teens, when he joined fiddler Jimmy Lunsford in a band which worked over WISE in Asheville, North Carolina. In 1943, Red joined Wade and J.E. Mainer for a BBC program “The Old Chisolm Trail,” a broadcast which marked his first exposure overseas. Alan Lomax produced the program in New York, and it also featured the Coon Creek Girls, Burl Ives, Woody Guthrie, the blind harmonica player Sonny Terry and other notables.

Following that, Red joined Oscar Turner and the Farm Boys on WWNC in Asheville. The band included Lunsford and two other youngsters whose mark had yet to be made, Carl and John Paul (J.P.) Sauceman. Red also began working with a man who has since been a lifelong associate, singer/guitarist Fred Smith. Together they joined the Blue Ridge Hillbillies, a group led by the comedian bass-player Tommy “Snowball” Millard. The Saucemans were in the Hillbillies too, and so was still another aspiring youngster-Red Smiley, known then as A.L. Smiley to avoid confusion with Red Rector. In 1946, Dobro player Ray Atkins induced Red to join Johnnie and Jack’s new group at WPTF in Raleigh. Unfortunately the early Johnnie and Jack Apollo records do not feature the Rector mandolin. By the time they were made in 1947, Red had left and was replaced by another major mandolin stylist, Paul Buskirk. By this time Johnnie and Jack had left North Carolina for the Grand Ole Opry (a major move in their career) and Red had joined Charlie Monroe, who was then working at WNOX in Knoxville. Monroe’s popularity was then at its peak, and the band’s format provided an opportunity for its leader to display the talents of a fine mandolinist who did not sound like Charlie’s brother.

Some recordings were made for RCA soon after Red joined Monroe. They are Red’s first and show the work of an 18-year old who was already a fully developed professional. Particularly memorable are two songs, “Don’t Forget to Pray” and “End of Memory Lane” which feature mandolin duets by Red with sometime fiddler Orne “Buddy” Osborne.

In 1948 Red left Monroe to join Carl Story and the Rambling Mountaineers at WNOX in Knoxville. During the seven years he remained, he recorded frequently. The Story band was on both Mercury and Columbia and had regular releases. In addition Red guested on one session each with Reno and Smiley and Charlie Monroe. His mandolin is heard to advantage on Monroe’s “Time Clock of Life” and “Red Rocking Chair” and alternating with Don Reno and Red’s boyhood friend fiddler Jimmy Lunsford on “Choking the Strings,” on which Reno even calls him by name. Notable among the Story records of the period is “Love and Wealth,” on which Red sings a good lead vocal. Red left Story in 1955 and began a renewed association with Fred Smith, a partnership which has continued intermittently over the years and resulted in a fine County album several years ago, Recently Red has been touring occasionally with Bill Clifton, and the two have gone overseas several times. As this new partnership has flourished, both have felt the need to expand their vocal and instrumental potential. This spring they approached another proven veteran, Don Stover.

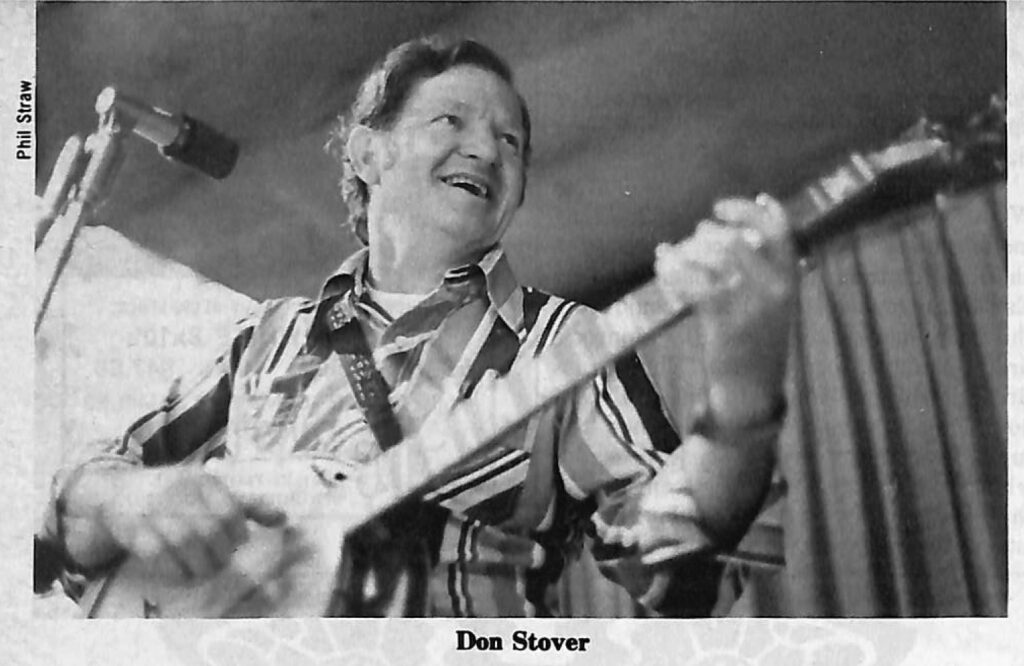

Don’s roots are deep into his native West Virginia, where he began learning mountain-style clawhammer banjo as a child. In his teens he was mesmerized by Earl Scruggs, learning what he could from the brief banjo breaks on Bill Monroe’s first Columbia records. As “Blue Grass Breakdown” and “Foggy Mountain Breakdown” were released, Don learned the tunes from the records as best he could, which was no small challenge considering that he’d never seen Scruggs play. By the late forties Don was working in the mines and playing locally with the Coal River Valley Boys. He came to know Bea and Everett Lilly and heard them regularly when they were working on the Wheeling Jamboree at WWVA with Tex Logan and the old-time banjo player Red Belcher, in Belcher’s Kentucky Ridge Runners. Belcher died young, but the Lillys kept the band together, calling on Don when Logan invited them to work in Boston while he was attending the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Eventually Don and the Lillys found a steady job at Boston’s Hillbilly Ranch, working there for eighteen years. Don left on occasion, once to work in Washington with Buzz Busby’s Bayou Boys, who had a daily TV show in 1954, and again in 1956 for a brief stay with Bill Monroe, with whom he recorded Bill’s first Decca LP “Knee Deep in Bluegrass.” That album contained a remake of “Molly and Tenbrooks” which showed how well the student of Monroe’s banjo player a decade earlier had mastered all he had learned.

Following Don’s return to the Lilly Brothers and the Hillbilly Ranch, they began to do some recording on their own, including albums for Folkways and Prestige and some singles for a small Maine label (Event) which have been gathered onto a County LP. These are the records which begin to reveal Don to advantage, sharing the singing with the Lillys and providing a banjo backing that was equal to the best. The Lillys left Boston in 1970 and Don worked the northeast with his own White Oak Mountain Boys for several years, producing several albums, including one blockbuster for Rounder called “Things in Life.” Recently he has moved back to the Washington, D.C. area.

Each of these three giants has worked both within and out of the bluegrass spectrum. Bill’s overseas appearances were often as a soloist and cast him as much in the role of a folk troubadour as a bluegrass practitioner. Even before that his recordings frequently leaned on old-time country-folk material fresh to bluegrass. Red’s mandolin style is unconventional in that it owes relatively little to that dominating figure, Bill Monroe. Though Monroe was an early idol. Red knew even in the forties that he would need to develop along significantly different lines to succeed. Part of his sound comes from his choice of a 1922 Gibson A-4 mandolin, which he has played since 1947 and which has a more mellow, less aggressive sound than the standard F-5. Two of Red’s other mentors are Paul Buskirk and Kenneth (Jethro) Burns, both of whom rely on extensions of the melody lines of their songs as opposed to improvisations based on chords. Red’s style is as “hot” as anyone’s, and it has the advantage of being uniquely his own and instantly recognizable.

Don Stover is no less an individualist. Within the strict confines of bluegrass his taste and inventiveness is unequalled. He never plays a tune the same way twice and his ability to think up new twists to add to old warhorses never fails him. “Things in Life” (the album and the song) reveal the full depths of his mastery as a singer, banjo player and even as songwriter. A complex original instrumental, “Black Diamond” (named for the coal he mined in his youth) and the title tune give full rein to his talents. The last is Don’s own composition too, sung with clawhammer banjo and as fine and emotional a country song as you could wish for.

It’s a little soon to say, but the variety of music we can look forward to from this all-star group should be enormous. They have already begun to work out some exciting vocal trios while still relying on the duets Bill and Red have developed. And Don is a natural baritone singer with the ability to blend with anyone. Each has their solo specialties and it will be interesting to observe how they are interpreted and expanded by the others.

Bill Clifton, Red Rector and Don Stover are three top men in their chosen profession. Each has his own sound which will form one of the building blocks of the of the new superstructure. The first test of their ability to mold their distinctive personalities into one unit will come with their singing, and in the few appearances they have made together the process is well underway. Clifton-Rector duets can already be heard on County and Bear Family LPs, and the trio is already working on new material. All three say they are uncertain about what directions they will take, but it should only be a matter of choosing among their many options. Each of them has a deep interest in old songs, especially the ones which lend themselves to bluegrass, and they are working on new material to complement the old. With the ingredients drawn from many years of collective bluegrass experience, Bill Clifton, Red Rector and Don Stover–The First Generation have much to offer.

Share this article

2 Comments

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Thanks for the post. It was refreshing to read again.

The first records that I bought was by Bill Clifton and the Dixie Mountain Boys on Starday records in 1956 when I was 13 years old.

I was hooked and have been a lover of bluegrass ever since, mainly the old time sound. You can’t beat Alex and Olla Belle, Red Allan, the Stanley’s and the list goes on and on.