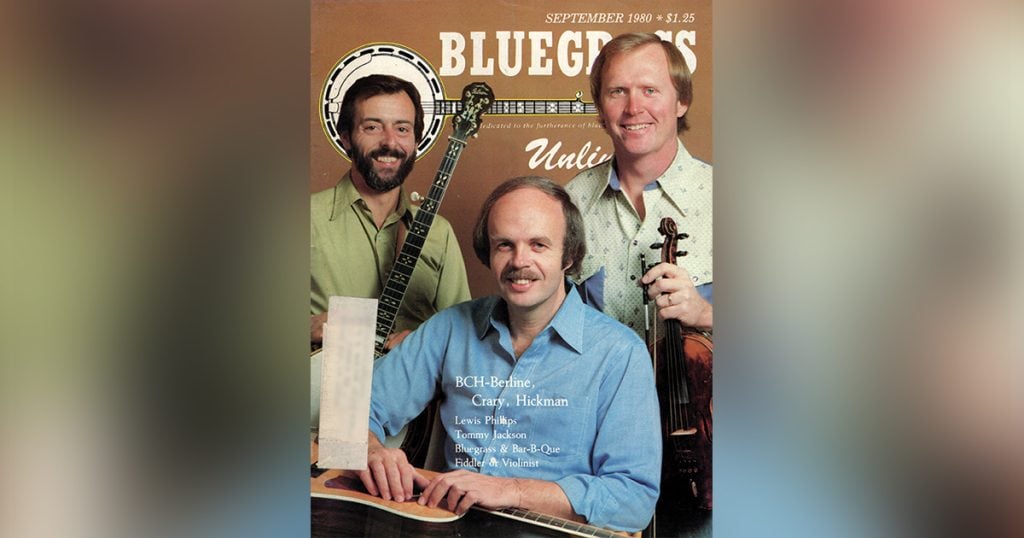

Home > Articles > The Archives > Berline, Crary and Hickman—Part 1

Berline, Crary and Hickman—Part 1

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

September 1980, Volume 15, Number 3

Your first reaction is a sinking feeling.

It’s a little akin to emerging from a crowded bus station with the sudden awareness of empty space in the hip pocket customarily occupied by your wallet.

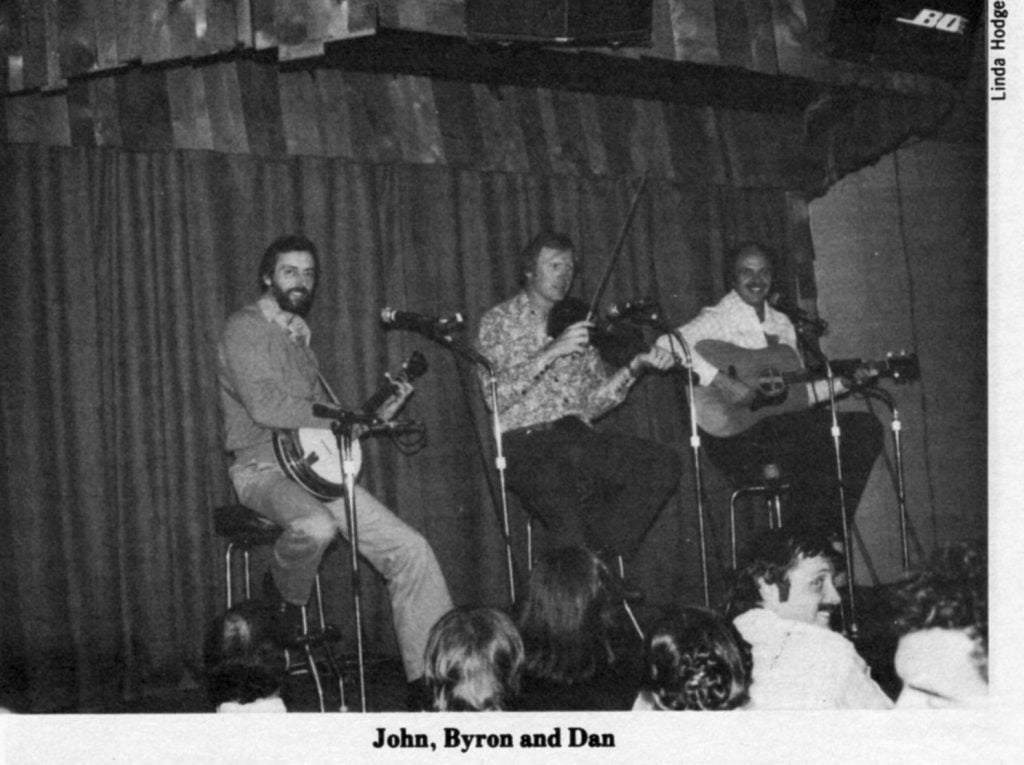

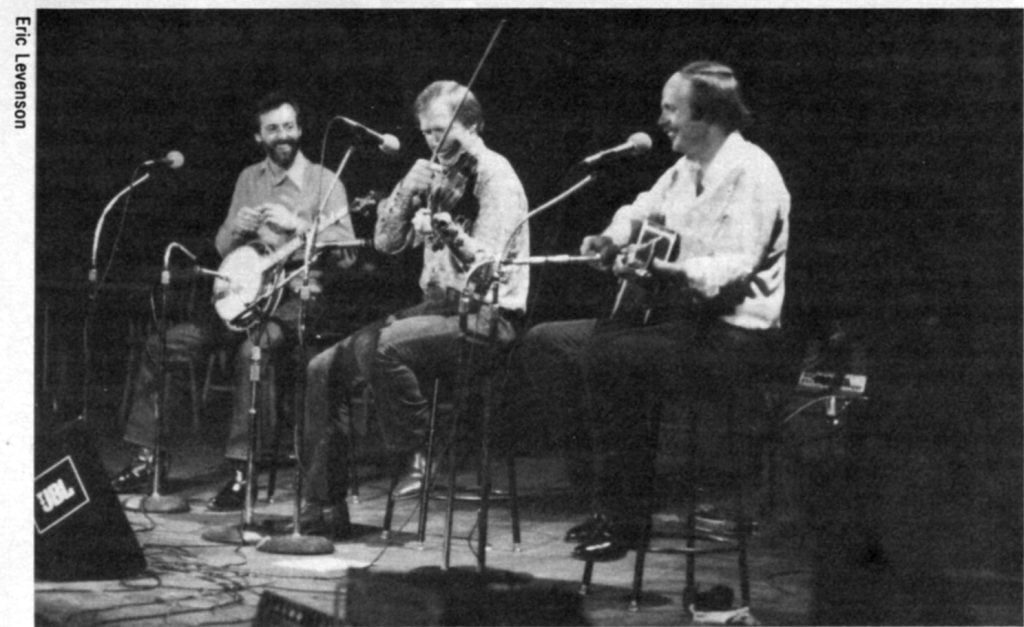

Berline, Crary and Hickman tune their instruments—fiddle, guitar and banjo respectively—and smile amiably. They seem quite relaxed, seated in straight-backed chairs only slightly above the level of those occupied by the audience. No bass player or other musician of any kind is in evidence.

Only three of them. No bass. All sitting down. No way it can be bluegrass. A queasy, weak sensation begins moving in, and you start feeling like a cornered animal. “Maybe someone’s going to throw his head back and sing ‘Michael Row the Boat Ashore!’’’ whispers an excited voice somewhere in your mind. You glance around hurriedly, searching for the nearest fire exit.

It’s another minute or so before you calm yourself with the realization that no one has either thrown their head back to sing or done “Michael Row the Boat Ashore” since 1963. Still it does seem likely that the fat cover charge to hear a high grade bluegrass show will have to be written off as a misguided investment.

Suddenly the music starts, and all doubts quickly evaporate. In startling contrast to the laid-back format, the music enveloping the audience is blistering in its intensity. John Hickman’s banjo drives, Byron Berline’s fiddle soars above and Dan Crary’s guitar propels the music with a mighty array of runs which weave in and out of the texture created by the other instruments. Soon the absence of a bass is forgotten.

The group’s timing is phenomenal. Each member is utterly sure where every note belongs. As a result each instrument is heard in glistening, three-dimensional relief.

The music is glossy, sophisticated and played with finesse. Yet it is also driving, energetic and vibrant. And it is definitely bluegrass.

Hickman’s banjo work is that of a master craftsman—solid, sensitive and constantly creative. His style is based on Scruggs’ with contemporary melodic playing interwoven in places. Traces of Don Reno and Eddie Adcock’s ideas surface occasionally, giving John’s playing an additional breadth rare among today’s banjo pickers.

Byron Berline is as deft as he is versatile, executing virtuoso fiddle maneuvers with an ease which belies their difficulty. He is one of the few great fiddle tune fiddlers who also exhibits an unerring instinct for just the right backup to highlight a vocalist or another lead instrument. There is great variety within Byron’s playing—hardcore bluegrass, Texas style, occasionally a Cajun feel. Nevertheless, as with Hickman’s banjo playing, there is a unifying and cohesive flow, not only within each song, but throughout the entire show.

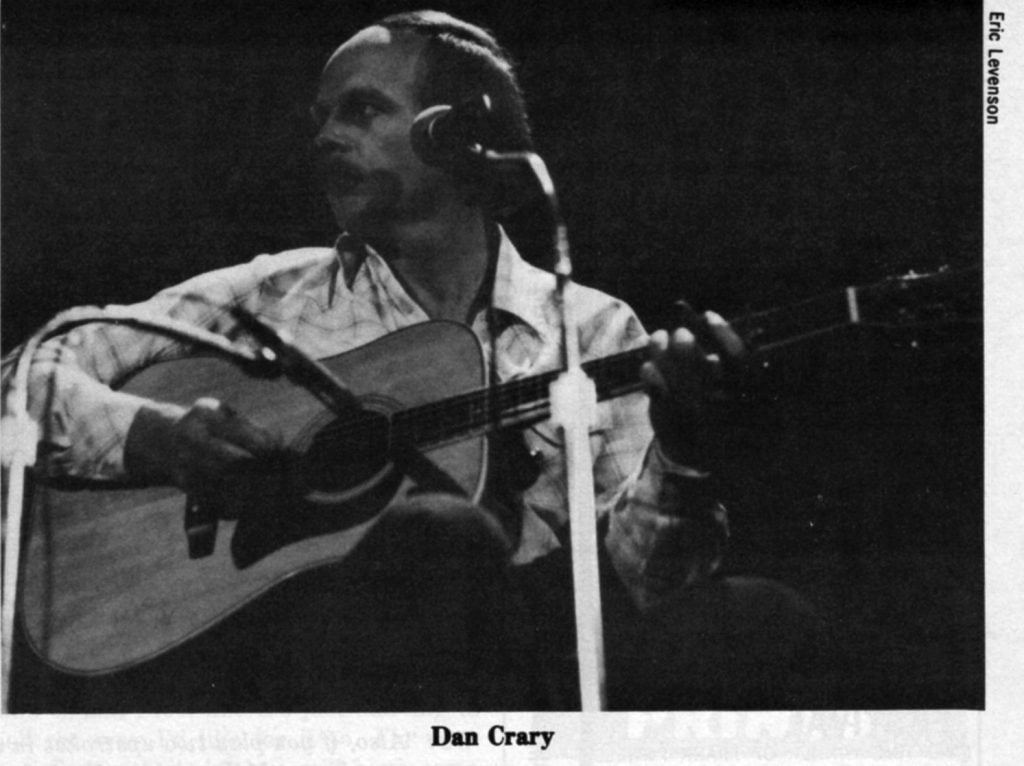

Technically, Dan Crary is perhaps even more astonishing than his colleagues. Both leads and rhythm work are smooth and exceptionally forceful. Whereas many bluegrass guitarists find themselves struggling to project their solos, Dan’s breaks thunder effortlessly above the backup instruments. There is a fullness in his sound—lots of open strings ringing in harmony with other notes.

Dan’s sizzling solos often contain an amazingly rapid flow of ideas. The listener in turn frequently finds himself waiting breathlessly to see whether Dan has gone off on a musical tangent which he will be unable to resolve. Remarkably, he always seems to return gracefully and authoritatively from each musical limb he ventures out on.

Even when the music stops, the BCH show moves right along. Between numbers there is pleasantly relaxed banter, much of it apparently quite spontaneous.

In introducing “Lime Rock,” Dan makes a point of thanking Byron for having played the tune better on Dan’s instrumental album, “Lady’s Fancy,” than on Byron’s own (“Dad’s Favorites”). “I guess by the time Byron did his own record,” concludes Dan happily, “he’d just shot his wad.”

Byron gets in his own good-natured digs later in the show. He asked the audience how many banjo pickers are present; how many fiddlers; how many mandolin players. When Dan points out that he hasn’t asked about guitar, Byron replies sweetly, “Oh, I just took it for granted everybody played the guitar, it’s such an easy instrument to play.” Dan is uncharacteristically speechless for 10 long seconds, while the audience chuckles and applauds.

Musically, the group is unique in ways other than its instrumentation and the individual abilities of its members. For one, it would be hard to think of another successful bluegrass band which does more instrumentals than vocals. (The ratio is somewhat around two to one.)

The tunes BCH select range from the bluegrass repertoire (Scruggs’ “Pike County Breakdown”, Reno’s “Dixie Breakdown” and Adcock’s “Turkey Knob”) to old-time fiddle tunes (“Dusty Miller,” “Lime Rock,” “Grey Eagle”) and quite a few excellent originals (“Don’t Mean Maybe”—the title cut from Hickman’s Rounder banjo album, “Huckleberry Hornpipe,” “Birmingham Fling,” “Byron’s Bark,” “Cricket” and “Passing By.”) “Red Bird” done as an unaccompanied fiddle and banjo duet deserves special mention. It evokes, without seeking to copy, the lovely feel of Paul Warren and Earl Scruggs’ banjo and fiddle duets.

Another standout is Scruggs’ banjo classic “Foggy Mountain Special” done as a guitar tune. It’s really fun hearing Dan start out duplicating Earl’s licks note for note, and then expanding on them. He even starts out one solo like Lester Flatt’s straight ahead guitar break. Rather than yield to the temptation to poke fun at the break’s simplicity, Dan is satisfied to add a few nice ideas of his own which preserve the flavor of the original.

Other Crary extravaganzas include his extended version of “Lady’s Fancy” and “The Devil Dreamed About Playing Flamenco With a Flatpick.” The latter is a kind of spoof, fusing the fiddle tune “Devil’s Dream” (which, it seems, is not one of Dan’s favorites) with some Spanish-sounding guitar ideas.

Several of the tunes have lovely harmony sections. Sometimes two or even all three instruments play carefully worked out harmonies. In their tour de force version of “Turkey In the Straw”, guitar, fiddle and banjo play one section as a round:

- Guitar plays the first line of the verse.

- As guitar plays the second line, the fiddle comes in and repeats the first line.

- Guitar now plays the third line, fiddle plays the second line and the banjo comes in and plays the first line.

- Guitar is on the last line, fiddle on the third and banjo on the second.

Etc.

This continues until the banjo has completed the verse twice. (The guitar repeats the last line three times at the end and the fiddle repeats it twice, so things come out even.) Then they swing into a final chorus, capping it with a fancy harmonized ending, and the crowd goes—understandably—wild.

By and large the group’s sound is very busy. If the fiddle’s out front, the banjo may be rolling along with it, not quite as loud, and the guitar punctuating not only with runs but with various rhythmic flourishes. When the guitar solos, fiddle and banjo may chop chords on the verse. When the chorus comes, the backup instruments diverge—the banjo still chording perhaps, and fiddle soaring off into long-bow harmonies almost like a string section. But, there appears to be no formula, and each tune comes out differently.

Another surprising aspect to BCH is that vocally they are not nearly as strong as they are instrumentally. Byron wryly acknowledges this onstage in introducing their trio version of the 50s Red Allen/Osborne Brothers song “Teardrops in My Eyes.”

“Here’s some three-part harmony. This is our strong point,” he quips, “so pay attention.”

Although Byron himself sings lead on “Teardrops,” most of the vocals are Crary solos, with occasional harmony by the others. Dan’s candid off stage opinion is that “our greatest weakness is that we’re all baritones. And three ‘barrelltones’ in a trio is not a wonderful trio. I wish we had a good solid lead singer. I mean, when I’m the best singer in a group, you know you don’t have a great singing group.”

In actual fact, having an exceptionally fine voice isn’t necessarily a prerequisite for putting a song across to an audience. Johnny Cash, Norman Blake and Bob Dylan, to mention just a few, have managed quite well without the power and range of a Bobby Osborne or the vocal sophistication of a Lester Flatt. Of course. Cash, Blake and Dylan aren’t bluegrass singers, but Crary’s vocal material isn’t bluegrass either.

Most of it is contemporary in character, and it includes tunes by John Hartford, Doug Kershaw and John Sebastian as well as some by Crary himself. Perhaps the most successful of Dan’s own songs is “Sweet Southern Girl,” the title cut from his recently released Sugar Hill album.

Every good singer, great vocalist or not, convinces his audience of the reality—for him—of his songs. The greatest trained opera singer in the world couldn’t sing “Molly and Tenbrooks” convincingly. On the other hand, when you hear someone like Hank Williams, or today’s C&W outlaws sing about drinking and cheating, it is painfully obvious that they are singing from real life. In other words, choice of material as well as vocal quality are important.

“The Devil Played the Fiddle” is Dan’s most dramatic and, in a sense, most ambitious song. It portrays a potentially murderous all-night dance presided over by a satanic fiddler. The song’s focal character is a young country hell-raiser caught up in the emotional upheaval produced by the dance itself, whiskey, desire, and jealousy at seeing a city slicker successfully moving in on his girl.

Byron does a marvelous job of setting the scene with a moody and faintly ominous fiddle background. His Cajun-style breaks fit perfectly with the dangerous exuberance of the dance Crary vividly describes:

Verse (understated, a little eerie):

It was a summer storm with green trees wattin’

But now it’s blown by, in the sky there’s a raven.

Wind off the river still smellin’ of rain.

Now the world’s gettin quiet, but in me there’s an achin’ pain.

Chorus (intense and raspy):

When you dance to the fiddle it’s the world that’s a-turnin’,

The music is the pain, the laughin’ and bumin’,

Played through the night til the cornin’ of day;

(Quieter)

And in the cold and the fog all the people gonna fade away

Dan is a perceptive, articulate and hardworking college professor, none of which is at odds with the image he conveys onstage. He is a sensitive and cultured educator/musician betraying certain soft edges that most of us get from a materially comfortable—if overbusy— life, filled with work that is more mental than physical. If he were only gaunt, dissipated and somewhat wild-eyed in appearance it would be so much easier to accept his growling:

Liquor in my belly and blade in my hand,

Great God, can’t they see it when they’re walking on quicksand!

Despite good lyrics, sensitive arrangement and beautiful playing, the contrast between singer and song strains the credibility of both.

Similar stress occurs in “William Socrates Brown,” Dan’s song about his grandfather, a stockyard worker and generally rough customer. It crops up again elsewhere, as in “Jesse James Was An Outlaw,” a gravelly-throated bluesy number about a modern outlaw who, mounted astride his 1959 Harley Davidson Knucklehead motorcycle, inspires fear throughout the surrounding countryside.

In fairness, it should be pointed out that audiences do respond well to these songs. The arrangements are uniformly good and Dan takes some of his most impressive solos on them. Still, it seems that finding—or writing—more appropriate material would additionally strengthen this already most impressive group.

It’s always illuminating to talk with people at the top of the music profession. Perhaps we just want to see what—in addition to their innate ability—equipped them for success in a difficult business.

Byron Berline grew up in Oklahoma with a lot of fiddle music in his life. His father played (providing Byron with the inspiration for his “Dad’s Favorites” album), and took his son to numerous fiddlers conventions. After a time Byron was entering them—and winning.

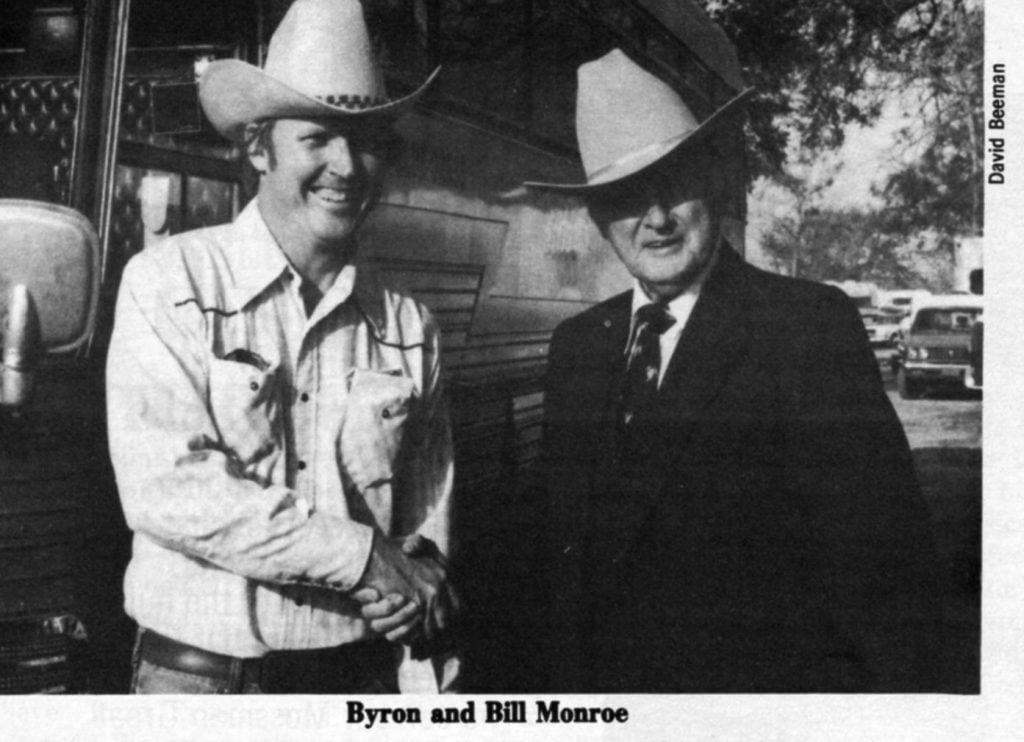

His early musical orientation was toward the Texas—style fiddling prevalent in his area of the country. When he began tuning in to bluegrass, however, Byron got deeply into it. So successful were his efforts that in the latter 1960s Bill Monroe offered him a job. During his short tenure with Monroe (prior to going into the service) Byron cut some excellent fiddle instrumentals including the popular “Gold Rush” and a fine “Sally Goodin.”

A multitude of pickers would be happy—indeed overjoyed—with the prospect of a secure spot in a well-established band on the bluegrass circuit. Byron, however, headed west to Los Angeles. The result has been a succession of diverse and interesting musical endeavors.

Before long Byron had solid credentials in LA’s affluent corporate music world, doing session work and movie soundtracks. Among the more unusual of his many recording sessions was cutting “Country Honk” with the Rolling Stones. Mick Jagger thought the sound they were getting in the studio was “too slick.” He therefore insisted that the session be moved outside into the street, microphones, wires, and all. There, to the astonishment of passersby—and of a nearby construction crew which was told to hush up during the recording—the cut was completed satisfactorily, traffic noise and all.

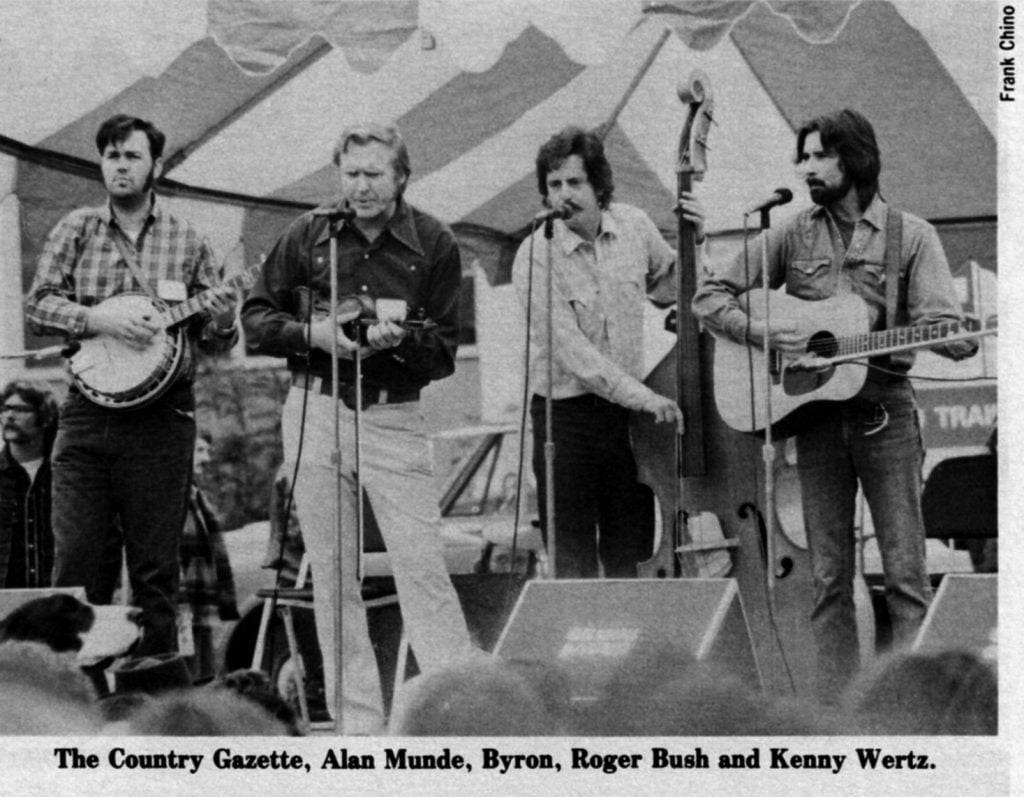

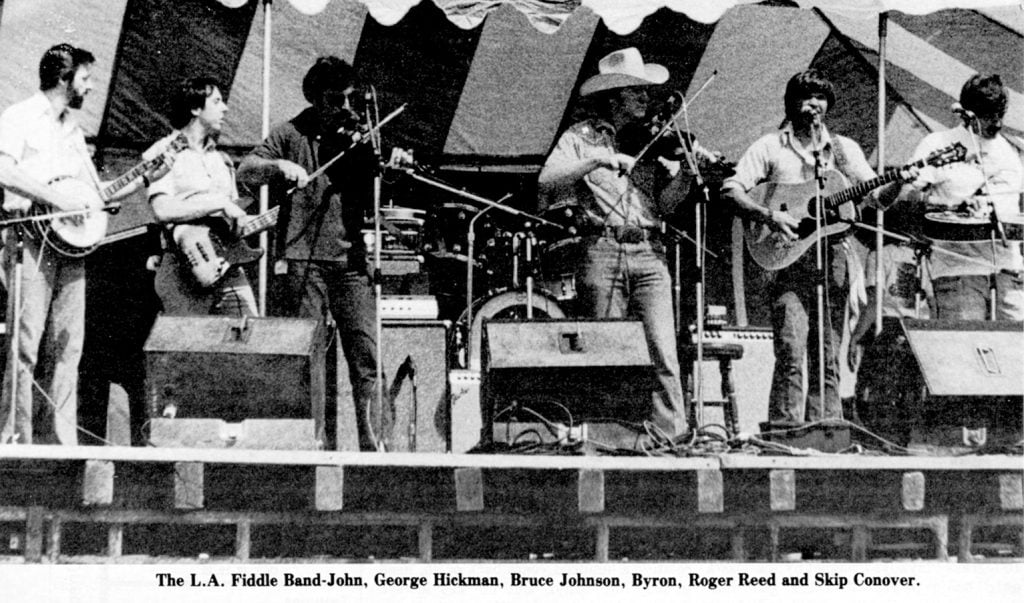

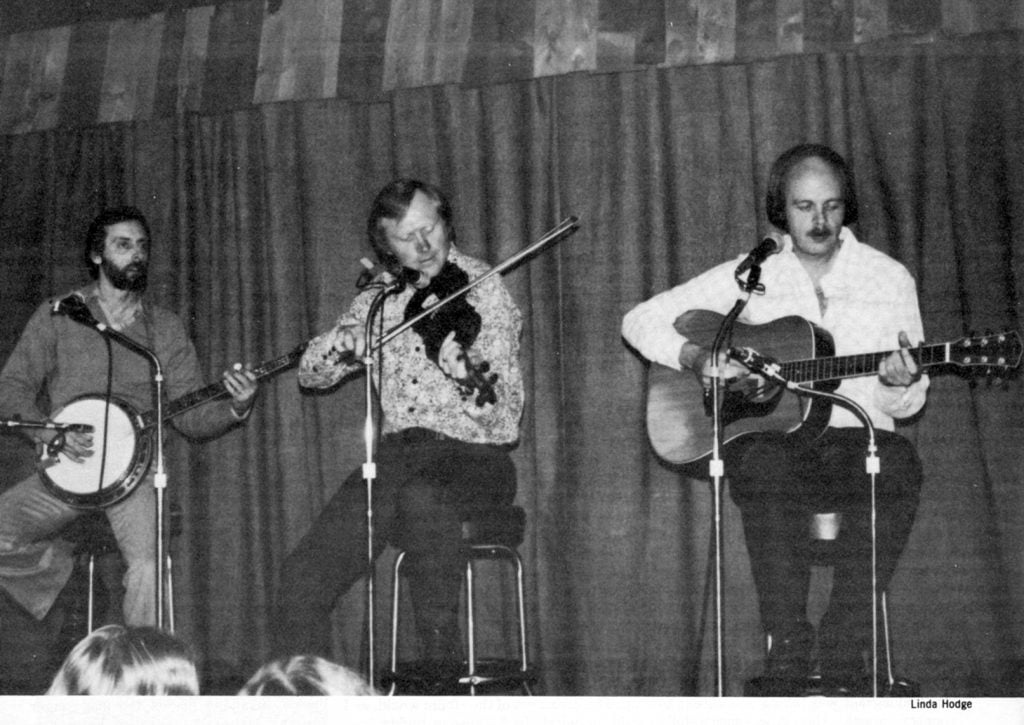

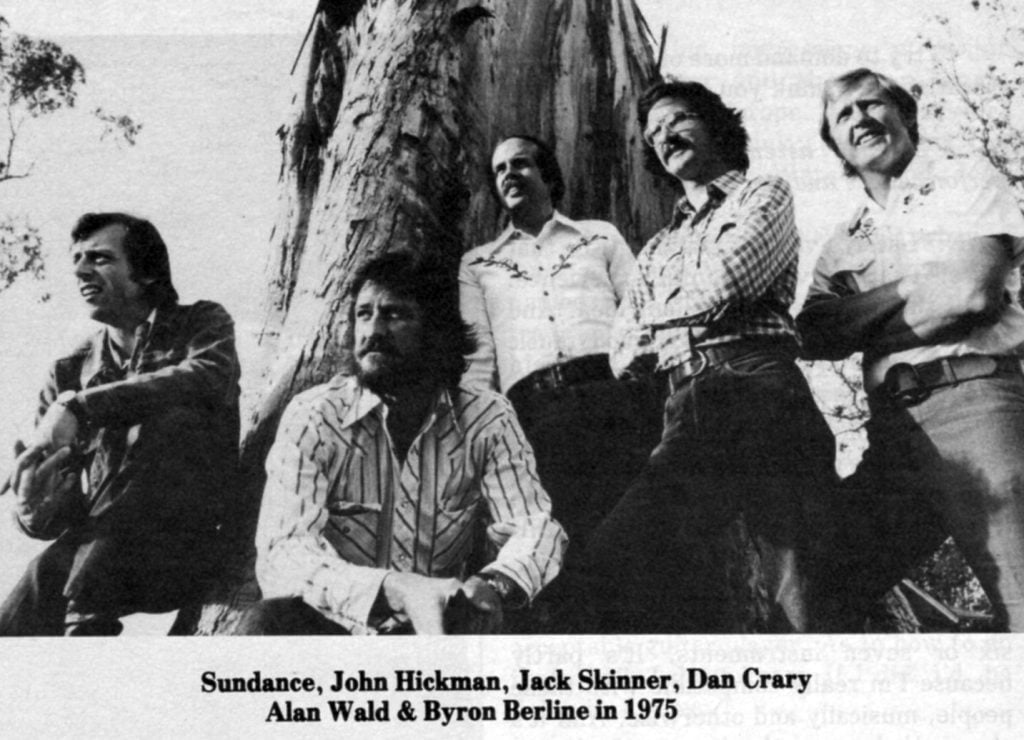

Since then Byron has played with the Flying Burrito Brothers, founded Country Gazette, and started—with Crary and Hickman—the now-disbanded pop/country rock group, Sundance. His latest album is “Outrageous” on the Flying Fish label, with Dan, John, Skip Conover on Dobro, and a variety of studio musicians.

Byron also performs periodically with Mason Williams and various symphony orchestras doing bluegrass arrangements with classically trained musicians. On Monday nights, when he’s home in Los Angeles, he presides over an informal evening of tasteful electric music, highlighting various guest musicians who drop in at the club where they play. And, if you happened to see the Bette Midler movie, The Rose, you may have noticed that Bryon somehow turned up in that, too.

Onstage John Hickman is the quiet one, leaving the song introductions and banter to Byron and Dan. Off-stage he is personable and articulate as he talks about his music and the band:

JOHN: “I grew up in Columbus, Ohio. I was about 13 when I really got into it from a man in the neighborhood who had all those old Flatt and Scruggs records. He had a banjo. I traded a guitar for it and started playing.

“At that time I just used two fingers, but I knew something else was going on. Finally, I saw someone using three fingers and picked it up from there.

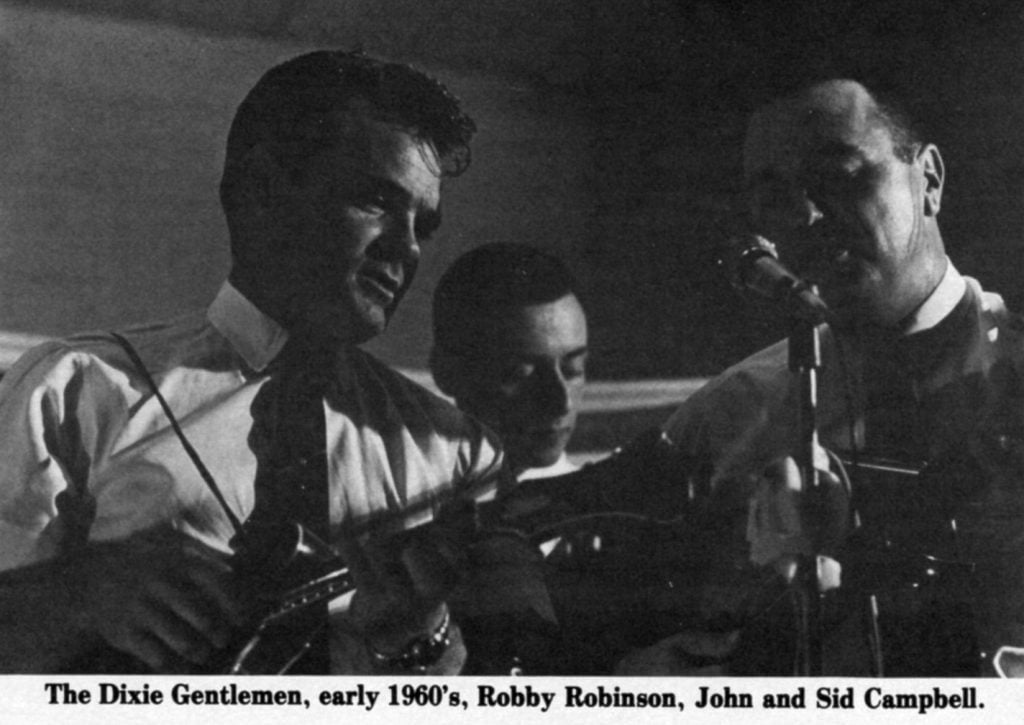

“Sometimes Elmer Burchett of the Bluegrass Playboys dropped by; he was a good banjo player. And the guy that designed the Fender banjo, Robbie Robinson, he showed me some other stuff.” (John would later play locally in groups that included Robbie, Pee Wee Lambert—mandolin player on the early Stanley Brothers’ records, (See BU, Jan. 1979), Sid Campbell, Danny Milhoun and Earl Taylor.)

“At that time I just played the reverse type roll and Robbie showed me how to do the other one—the forward roll. It really blew me away! I thought, ‘God, here’s something else I’ve got to learn! I’d done spent a year on the reverse roll.

“So it probably took three years to figure out everything everybody was doing with their right hand. But today you can do it in five minutes. Or you can at least tell somebody how.”

BU: “There are plenty of books and teachers these days.”

JOHN: “Yeah, but somehow I don’t regret taking all that time because it seems like you get everything more solid that way. You gain something. You learn how to play all those tunes in a lot of different ways.

“I played ‘Foggy Mountain Breakdown’ with just one kind of roll at first—then I changed it and played it another way and another way.

“Learning like that I think you lock into something that’s a lot more comfortable for you than learning exactly the way it says on a piece of paper. The arrangement on the piece of paper was just comfortable for whoever wrote it.

“Nobody on either side of my family as far back as anybody could remember played anything—except for one distant relative a hundred years back or so, used to play the banjo. But he was always drunk and in jail, so they thought it wasn’t so good that I try to do anything with it!

“He’d go out and kill everybody’s cat in the neighborhood, making banjo heads and stuff. (Laughs) He was the black sheep of the whole family; he never worked or did anything, he just drank as much as he could and played the banjo!”

BU: “Is that what draws people to the music, so they can live that way?”

BYRON (Smiling broadly): “I don’t know why everybody wouldn’t want to do this kind of life! We were talking about that the other day. So much fun. We get to stay up all night and don’t get any sleep much, you know. Eat whenever you feel like it. It’s a great life!”

JOHN: “Well, it is fun the way we do it. We go out not that many times a year—we don’t travel year round. Play two or three weeks maybe once or twice a year, and it’s really something to look forward to. Everything just works a lot better that way.”

BU: “You all look real relaxed onstage. ”

BYRON: “Yeah, we sit down! Actually, it was Crary’s idea. It wouldn’t make any difference to me. John’d rather stand up, wouldn’t you John?”

JOHN: “Yeah, it’s easier for me to maneuver the banjo around. Standing I don’t have to lighten up a lot in the background; I can just move back from the mike. Sitting down it’s really different.”

BYRON: “Sometimes we do stand. It depends on the place.”

JOHN: “Probably with just the three of us and no bass, it looks better sitting and goes over better.”

BYRON: (Grinning) “We make the audience stand up and we sit down!” (Laughter)

BU: “How is it, playing with no bass?”

JOHN: “Right at the beginning each time we’ve done this kind of thing it’s a little tough for me, because the other bands I play with out in California usually have a bass. But it’s OK after you start getting a little more comfortable with it. It’s not that bad if you get used to playing without it, but at first it’s really weird.”

BYRON: “Crary plays so strong it really fills up the rhythm stuff—even when he takes a break.”

JOHN: “Well, a bass might come about sometime, but it’s something a little more unusual about what we do, I guess, that we don’t have one.”

BU: “What players have you listened to?”

JOHN: “There’s something I like, I guess, about all of them. I’ve listened to all of them but mostly in the past few years it’s right back to Flatt and Scruggs. It seems like every time I sit down to listen I drag out these old 50s recordings I have on tape of their live shows and it just fascinates me more every time I hear it. The way Scruggs did it, he just about said it all.”

BYRON: “I listen to that stuff too. I like live tapes a lot. They seem to have more excitement to them than just regular records. But what type I listen to most, I don’t know. Mostly bluegrass, I guess.”

JOHN: “I like to listen to a little bit of everything, just to see what’s happening.”

BYRON: “And there’s so much stuff happening. Everybody’s recording. Every day something new comes out—a new group’s popping up here, here and over here.

“Out east here, Doyle Lawson’s got a group now; Jimmy Gaudreau’s got him a group over here; so-and-so else split over there and got a group. It’s a big card shuffle. That’s the way it is in L.A. too. You never know who’s going to be playing with each other.”

JOHN: “It seems to be the way things are these days—everybody shuffles around a lot. Nobody seems to pin down exactly what they want to do. Maybe they just don’t commit themselves to anything in particular til they decide what they really want to do.”

BU: “Very different from the early days of bluegrass. ”

BYRON: “Yeah! ‘You play with me, boy. Don’t you be playin’ with anybody else! And don’t record with anybody else!

“I asked Paul Warren (Flatt and Scruggs’ fiddler for many years) one time, ‘When are you gonna cut a fiddle album?’

“ ‘Never.’

“I said, ‘Why? All those fiddle tunes you know, you ought to have ten of them out!’

“ ‘If I want my job, I can’t.’

“Well, you see, it would have helped the band. But they didn’t think of it that way.

“I find it a lot of fun just to be able to play different types of music—not only bluegrass. Once in a while I’ll play some real old country and western, cowboy music. There’s a lot of it out west—all the Bob Wills kind of stuff.

“In fact, the Sons of the Pioneers asked me to play with them. They play a lot in Vegas, a lot of rodeos or what have you. I thought it was a nice honor, although I couldn’t do it.

“I can just imagine myself—(sings, a bit operatically): ‘Hear them tumbling down…’ ”

BU: “What about some of the different groups you all work with?”

JOHN: “There’s a bluegrass band I work with called Cheyenne—a real good vocal group, and pretty bluegrassy. We’ve got some really good trio singing and some good gospel quartet stuff too. Byron has this electric group that plays one night a week, and sometimes I play with them.

BYRON: “It’s just something (Dobroist) Skip Conover and I put together. The reason I wanted to do something like this is I wanted to have a band where anybody could come and sit in.

“I really enjoy playing with a lot of different people, people like James Burton, J.D. Manness—he’s a real good player—and another guy named John Hobbs. We just play Monday nights at this place where a guy I know has a little bar. There’s no cover charge; it’s just a drinking bar—pretty good stage. Steve Goodman came in the other night. People like that just come circulating in.

“We try not to get loud, but sometimes it is. Depends on whether Vince Gill (Pure Prarie League guitarist, former member of the Bluegrass Alliance, Boone Creek, and Sundance) is with us. And there’s a drummer who drives all the way from Death Valley, which is two or three hundred miles, just to play. He’s a great drummer and singer named Steve Spurgeon.”

(Byron and John regard these other groups, however, as sidelines, and would like to see their band with Dan play an increasingly important role.)

JOHN: “We’re pretty much playing the music we like now.”

BYRON: “I’d like to keep it bluegrass, too. We’d just like to do more arrangements on some tunes like “Turkey in the Straw.’ ”

JOHN: “This is what we want to do. Lock it in—possibly get a bass player—and really tighten it up.”

Berline, Crary and Hickman—conclusion

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

October 1980, Volume 15, Number 4

Before continuing with Dan Crary’s thoughts on music and BCH, it might be worth pointing out that by no means all musicians are candid when being interviewed. At times, it can be hard to get anything deeper than: “It’s great to be here: this is the finest crowd we’ve ever played to. We just broke all attendance records at Caesar’s palace. We’re already booked solid through next summer. Our new album is really taking off; it’s number one on the country charts in Bulgaria.” While the above incident may be slightly exaggerated (but not much), the following scene is absolutely true. (Only one name has been changed to protect the guilty.)

One of the most revered living bluegrass musicians is being interviewed during a workshop by a college professor who is also quite knowledgeable about bluegrass. The band of this musician (let’s pretend his name is Clint Flatwoods) is also present. After talking with Clint for a while, the professor begins asking the sidemen about their musical backgrounds.

Who did you listen to when you were starting out?” he asks musician #1. “What performers influenced your playing?” Under Clint’s watchful eye, musician #1 answers, “Clint Flatwoods.”

“How about you?” the professor asks musician #2.

“Clint Flatwoods,” says musician #2. “Anyone else?”

“No, just Clint Flatwoods.”

Musicians #3 and #4 follow suit with the same reply. The observer has little doubt that, had they been placed on a medieval torture rack, their stories would have remained grimly unaltered, even as bones splintered and eyes were plucked from their sockets.

Nevertheless, common sense tells us that finding a musician who has really paid attention to only one single performer would be quite hard. Assembling four in one room would be, in Biblical terms, like getting a camel through the eye of a needle—or a rich man into heaven.

In fact, musician #1 sings lead remarkably like Bill Monroe, and therefore surely has listened to Monroe’s music quite carefully. Musician #2 played and recorded for years with another group, playing in a quite different style; he only changed to his present style because Clint Flatwoods wanted him to.

This is mentioned, not as a putdown of any kind, but to point out how refreshing it is to talk with professional musicians who apparently do not need to tailor what they say for public consumption. From quotes earlier in this article it will already be quite candid. Dan, in particular, shows himself little or no mercy when it comes to self-evaluation. This tendency is, happily, balanced through by a pretty realistic perspective on his achievements, a keen appreciation of his musical colleagues, and a certain sense of humor about the world of music.

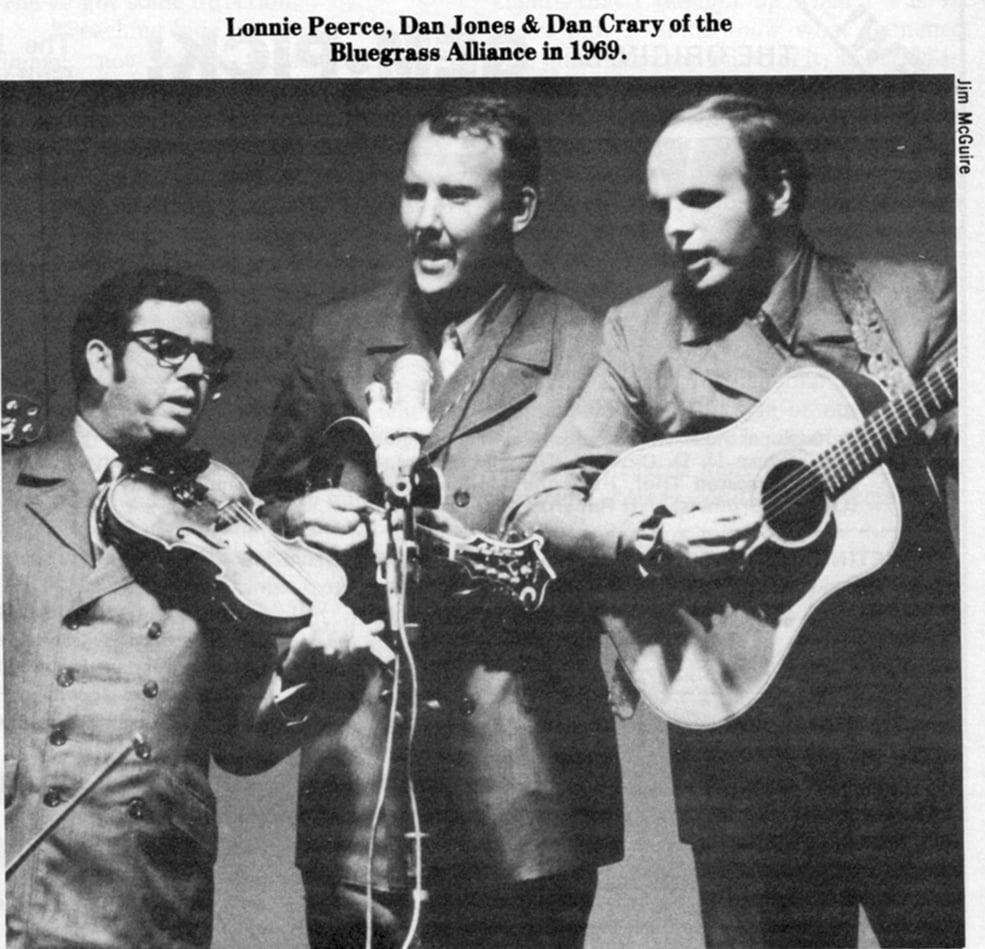

BU: “Many bluegrass fans first heard you about ten years ago, after you joined the Bluegrass Alliance. [The band’s albums, as well as Dan’s first solo guitar album are still available on the American Heritage label] Looking back, do you have any thoughts on the Alliance’s contributions?”

DAN: “I’m sort of proud of that band in a way. Partly because I think we accomplished something, and it was in the face of great odds. We had a lot of weaknesses in the group.

“I was one of the great weaknesses. When we started out I didn’t know the first thing about how to play bluegrass music. And there were others—which I won’t comment on—but I think that in our best moments we made damn good music, in spite of our handicaps.

I have been told that even though I certainly was not the first person to play lead music on the flat top, at the time not much of anybody was doing that in a bluegrass band. We went down to our first festival in 1969 at Reidsville, North Carolina—I still have a tape of that. The music I was playing as a lead guitar player was something short of wonderful, but the reaction we got was that people were surprised that a band would have a lead guitar playing a break in everything.

“Now Clarence White had done it magnificently years before, Don Reno had done it, Scruggs had played guitar beautifully in the 50s and Charlie Waller took a break once in a while. Even though it certainly had been done, it happened that we came along and featured the guitar when it seemed like it had died out in bluegrass bands. If I’m right about that, then I guess maybe we did have some influence.

“I don’t want to claim too much here. I hope that as a band we influenced the resurgence of interest in guitar as a lead instrument in bluegrass. If that turns out to be true historically, I’ll look down from glory—or up from perdition or whatever—and be glad.”

BU: How do you like working with just guitar, banjo and fiddle?”

DAN: “It’s really interesting to work with only two other musicians, especially for the guitar player because it puts other constraints on the guitar. The guitar has to carry things it doesn’t have to otherwise. But whether I like it or not depends on who the other musicians are.

“Now with these guys, as far as timing is concerned—these guys don’t need a bass to keep them on the beat. So I really like it when I work with them. They are so precise—such out of sight musicians—that we don’t need a bass to keep it together.

The result is that I don’t have to struggle to be heard. It gives me a great deal of freedom—and I’m still kind of thrashing around, figuring out what to do with it. Sometimes I get a little frazzled and at loose ends with it.

“The bottom line is: I like it a lot!”

BU: “You don’t miss hearing the low range sound provided by the bass, even though you may not need it for rhythm?”

DAN: “Well, the three of us haven’t worked in this combination with a bass at all. If I heard it with a bass, I might say, ‘Hey, it would be nice to have that in there!’ But I don’t miss it. I’m satisfied with the way it is now.

“And there are some advantages. Like not having to carry a bass around. Like it’s simpler to have three people instead of four.

BU: “Do you spend much time practicing guitar these days?”

DAN: “Regrettably, no I don’t. When I practice it’s when I have to—if I have to learn a new tune. (Pauses) Well, yes I do, but not very systematically.”

BU: “You’re busy with a full-time teaching job?”

DAN: “Yes, very. I don’t know anybody that teaches full time in college—that does any good at it—that doesn’t spend 50 to 60 hours a week at it. And when I come home at 10 o’clock at night after teaching a three hour class or something, all that’s left is the rear end of the day, and it’s no time to practice. So a lot of the time, I don’t.

“And I absolutely don’t advocate that. I think serious musicians should play everyday and practice systematically. But I don’t.”

BU: “You mentioned singing as a problem area.”

DAN: “I’m not satisfied with it. But, I like to sing; I like to play guitar in vocal music. I think that’s what I like to do the best. Whether it’s in a group or singly, that’s what I really like to do.

“Among my favorite kinds of music in the world—not speaking of myself, but what I like to see—is a really good guitar player/singer. I’ve lately gone around the world collecting impressions of guitar player/singers, and there are some fabulous ones in Europe. I heard several in Ireland that I think are at least the equivalent of Doc Watson and Jose Feliciano.

“One is a guy named Dick Gaughan, a Scot, and another one is an Irish guy named Paul Brady. Brady is doing Irish traditional music plus he’s starting to do his own more contemporary music. Gaughan is a traditional singer who does ballads and traditional songs of one kind or another. To me, that’s a really great kind of music, and I want to do that, both singly and with this group.

“I’m not satisfied with my singing and I think I have to fight harder to be an acceptable singer than I do to be an acceptable guitar player. As to how to do that—hell, I don’t know. If I did, I’d be doing it, I guess.”

BU: “Have you perhaps put more emphasis on your guitar playing over the years than on singing?”

DAN: “Yes, I’ve gone about it more systematically. But I think a lot of it has to do with what you demand of yourself. And I think my singing is better than it used to be, just like my guitar playing is. To the extent that it is, it’s because I kicked myself a lot.

“I try to demand more of myself. I get dissatisfied. I think you have to do that.”

BU: “Do you listen to tapes of your performances and try to evaluate them?”

DAN: “Lately I’ve been starting to do that more. That’s a very painful experience. But I think that’s an excellent idea. And anyway, you’re not making good music unless you’re experiencing some pain.

(Laughs) “That’s what art is all about: pain and agony made beautiful!

“But this group—I really like playing with a group. I’ve found more freedom to feel around—I hope creatively—with this group more than any group I’ve been in.

“It’s partly because it’s not a cluttered group, in terms of there aren’t six or seven instruments. It’s partly because I’m really compatible with these people, musically and otherwise. And it’s also partly because they’re sort of tolerant of a guitar player doing unorthodox things—which, God knows, I like to do—and they’ll let me do it. So it’s fun and it’s creative.”

BU: “The three instruments do work together very effectively; you have a variety of textures —different instruments back up in varied ways. You’re able to sustain interest even though you do a lot of instrumentals. ”

DAN: “That’s something we’re striving for and I think we’ve been partially successful at it. A lot of that has to do with looking for stuff and also with whatever chemistry is between musicians, and I think that’s pretty good among us.

BU: “Everyone seems real loose, which you often don’t see. A lot of times you see musicians who look like they don’t want to talk to each other.”

DAN: “A lot of times we’ve had that (in past groups). And a lot of times you may be in a group with musicians that you can’t count on. Or they feel like they can’t count on me, or whatever. Whether that’s true or not, if you feel that way you don’t really feel free to bust loose and do what you’re able to do.”

BU: “To change the subject a little, have you ever taught guitar?”

DAN: “Yes, I have. I taught guitar at various times part time and at various times full time. I’m not teaching guitar now. It’s really hard work, too.

“And when you find a guitar teacher, don’t believe him if he tells you, I don’t play that, but I understand it and I can teach it to you!

“When you’re in the guitar teaching business, someone walks in, and they say. ‘Well, here I am, and here’s my guitar I got for Christmas. Teach me to play.’

“And I say, ‘What kind of music do you listen to?’ And they say, ‘I Dunno.’ There is a really difficult person to teach music, because they have no real motivation.

“But if they say, ‘I heard this guitar player and that’s what I want to do,’ then you’ve got some direction.

“Teaching kids who are going for an image, not for a particular kind of music—I found that to be real tough. Rewarding at times, but very difficult.”

BU: “Some of the variations on crosspicking, especially certain accompaniments, seem to be unique to your style. Is there any way to describe what you’re doing?”

DAN: “I sort of have an idea of where it came from. I learned guitar all by myself—I started when I was twelve years old, and I was the only guitar player I knew. If you can imagine that! Nobody played the guitar in the 50s.

“I took some lessons from a teacher when I first started out. But when I quit taking lessons, I was the only damn guitar player in the world I knew.

“So when I heard somebody fingerpicking on the radio, for all I knew they were doing that with a flatpick. I didn’t know what fingerpicking was. So I started imitating fingerpickers with a flatpick. Which is a pretty good way to get ready for crosspicking, when you learn what that is.

“So I’ve just always done that. And jumping around from string to string—I’ve never been afraid of it, because I thought that’s what you did.

“The first flamenco I heard—as far as I knew the guy had a plectrum in his hand. So I started fooling around, trying to imitate that. That’s how that foolishness on that one song (‘The Devil Dreamed About playing Flamenco With a Flatpick’) came about. Those were runs—many of them—that I thought up when I was 16 years old. I didn’t know what flamenco was and I liked the sound of it, so I tried to do it with a flatpick—pretty unsuccessfully. So I’ve always crosspicked in a sense.”

BU: “What is the difference between what you do, and what is usually thought of as crosspicking?”

DAN: “I guess I don’t think of it as a difference. Usually crosspicking is conceptualized on the mandolin as done in Jesse McReynolds’ style or on guitar as what you do on the chorus of “Beaumont Rag.” But that is limited to picking three adjacent strings, and I don’t think you have to do that.”

BU: “What about pick direction in crosspicking?”

DAN: “I advocate a down-up-down-up stroke because it keeps the timing right. Most of the people I know who don’t do that never play something the same way twice, because pick direction is never the same. Thus they never get in practice. And I think one of the things you have to do to get in practice on something is keep the pick going in the same direction so that you’re playing it the same way several times.”

BU: “Also, if you play two upstrokes in a row—as Jesse McReynolds does—[or, two downstrokes in a row] this probably limits you to adjacent strings. ”

DAN: “That’s an interesting point. I think that’s probably right. I’d never thought of that.”

BU: “Does that mean that you might do a crosspicking pattern where no two strings would be adjacent?”

DAN: “Well, I do one pattern in ‘Sally Goodin’ that goes: 6,3, 3,4,6, 2,3,4,6, 3,4,6 or something like that. Anyway it’s all over the place.”

BU: “Any thoughts on the guitar as a rhythm instrument?”

DAN: “Well, I was never a wonderful orthodox bluegrass rhythm player. Partly out of boredom of it, I think.

“That doesn’t mean I don’t have a lot of regard for the great rhythm players in bluegrass, because I do. You can’t underestimate the impact of a Charlie Waller or Rodney Dillard in bluegrass rhythm. My God, Charlie Waller has been the rock on which the Country Gentlemen have been founded for all these years. I think that’s tremendous and that kind of music needs that kind of rhythm.

“And I’m not the rhythm player for that kind of music. They would not want to hire me because I wouldn’t do anywhere near as good a job.

“On the other hand, rhythm doesn’t have to be one thing—it can be any number of things. Luckily for me in bluegrass groups I’ve played in, they didn’t want me to straighten up my rhythm playing bad enough to tell me to get the hell out. So they had to put up with my fooling around with it.

“So that’s what I do. I have more fun at it, I think, than if I were playing straighter.”

BU: “You don’t seem to give in to self-indulgence where you try to put more in than works in a given song. ”

DAN: “I am guilty of that on occasion. There are times when I do something that I’m afraid upstages the other player. I have the decency to feel guilty about it, but it doesn’t mean I won’t ever do it again.” (Laughs)

BU: “It does sound as though you’ve thought a lot about your rhythm playing, which is not necessarily true of all guitarists who play a lot of lead.”

DAN: “My goal is ensemble, after all. But it’s an ensemble in which I’m causing something to happen, even though another player is playing lead. I don’t want to bury that, and I don’t want to call attention away from the lead, but I want to have an impact on what that lead sounds like. And I’m willing for them to do the same thing when I’m playing lead.

“I do think that bluegrass music sometimes has been guilty of not focusing enough on ensemble and too much on the individual instrument. I’m a lot more interested in what we can all three do together than what we do one at a time.

“Now the old-time string bands, everybody played pretty much all out all the time, and I think one of the beautiful refinements that bluegrass brought was an approach to playing rhythm and playing backup that highlighted one instrument.

“One of the innovations of Bill Monroe was to have the fiddle player play solos, by himself. I think that was tremendous. Or listen to J.D. Crowe’s band. When they sing, the rhythm quiets down and they sing. Crowe’s feeling about that is: ‘Instruments lighten up and let the singing be heard.’ That’s a great effect. It’s a great sound.

“So I’m not saying, don’t ever have solo stuff stick out. I think you need the virtuoso player up there blowing people away—focusing on the one instrument. But I think rhythmically you can do things to enhance that. And so we try to play some harmony stuff, and we give it some all-out and on some we lay back and let one instrument be heard.”

BU: “In what kinds of places do you enjoy performing best?”

DAN: “Well, I like the Down Home (in Johnson City, Tennessee) better than about anyplace, with the possible exceptions of just a few others that are really comfortable. There’s nothing like having an audience be relatively quiet, sitting right there and digging what you’re doing. No festival can match that, just because of the intimacy of it.

“I like to play festivals too. But I like that intimate setting and people watching real closely. If you do manage to do something right, one guy’ll nudge another one and say something about it.

“Then, of course, you also have the experience, when you mess up, of seeing a guy who noticed roll his eyes toward the ceiling and go, ‘Oh God!’ or ‘Tony Rice wouldn’t have done that!’ But then, that’s good for you too.”

BU: “What do you feel regarding the band’s future?”

DAN: “I sort of see this group as getting started, even though we’ve all played together in one form or another for a long time. We’ve been doing the trio for sometime (since a tour of Japan in the summer of 1978). Still it’s been sort of off and on and I feel like it’s just starting to jell the way I’d like for it to. I’m very satisfied with it, but we still have some ways to go.”

BU: “Do you think it might turn into a full time thing at some point?”

DAN: “I don’t want to even think about that. The last time I got real involved in staking everything musically on a group (Sundance) I was real dissatisfied when it didn’t work out.

“I had a lot of fun with Sundance, but when it got really heated up and serious I couldn’t work around my school schedule. They were starting to tour and do record promotion and stuff and I was still teaching school. It was just impossible for that to work out with my schedule. I felt bad about not being able to continue to be a part of that.

This (the situation with BCH) is sort of like a relationship discussion, you know. Instead of deciding what it’s going to be like six months from now, you take it for now and forget the rest.

“I’m going to continue with the craziness that I do, so the music things are going to have to fit in around that. I don’t rule anything out, but I’m just not going to make any plans. (Smiles) Just what ever the Good Lord sends our way— lightning bolts—disaster—pain and suffering” (Laughs).

The Berline, Crary, Hickman phenomenon does have its dangerous aspect. In recent years there have already been more than enough aggressive young pickers taken with the idea that playing straight rhythm is “boring,” that playing busy or far-out backup will automatically impress people, that instrumental virtuosity is the most important element in a band, or that vocals are just something you throw in between instrumental breaks. Talented though some of these people may be, the music they make usually ranges anywhere from tiresome to awful.

BCH’s success could be superficially interpreted as an across-the-board vindication of these ideas. And this, in turn, conjures up oppressive visions of bluegrass audiences subjected to a deluge of young bands where everyone plays nonstop hot licks at every opportunity.

In fact the BCH approach works because all three are exceptional musicians who bring with them not only exciting originality, but also the maturity of solid professional experience over the years. Let’s hope they stay with it—we need them.