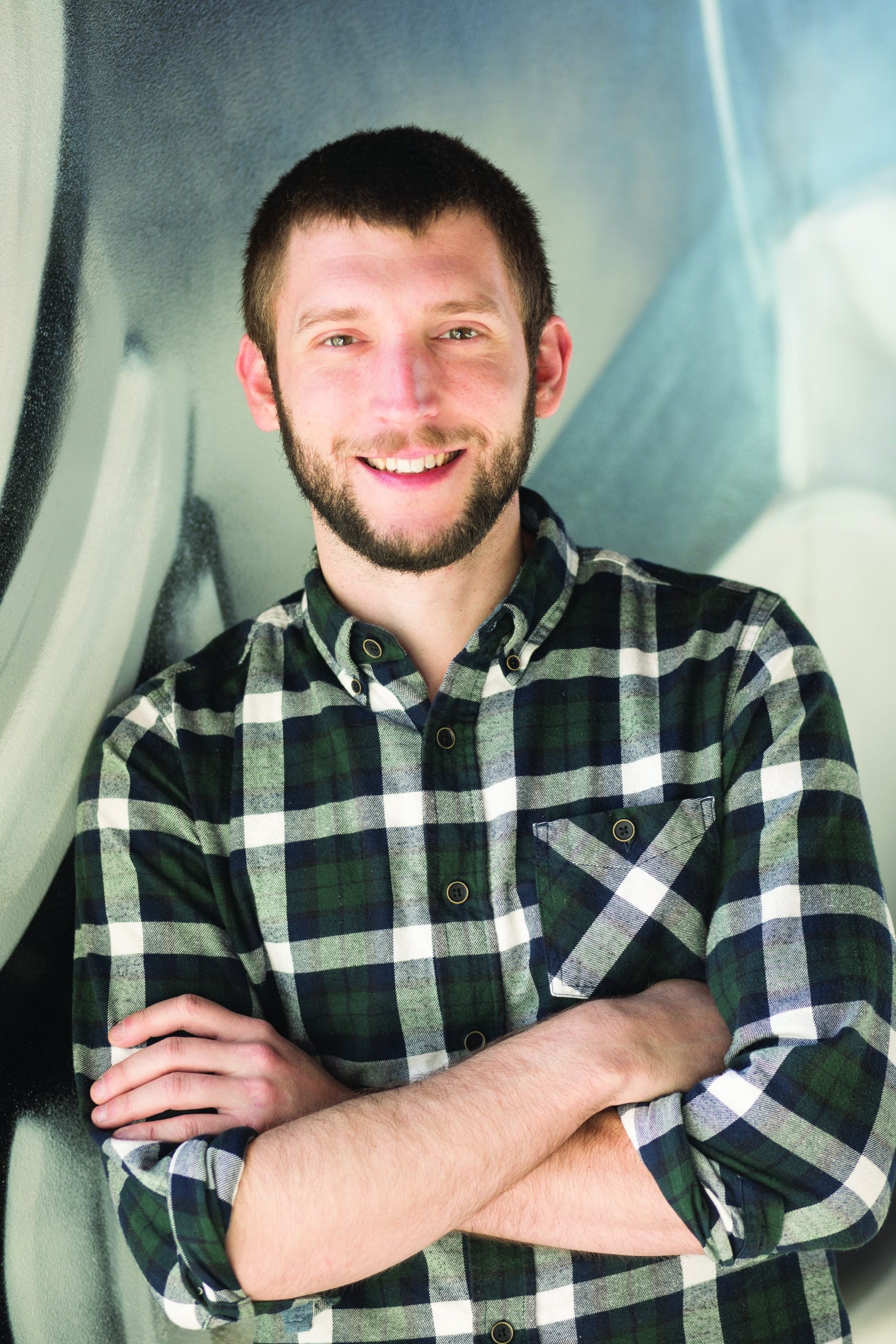

Ben Mason

Bluegrass Builders

Photos By Kristen Ellis Photographer

Not only is Kentucky home to legendary bluegrass musicians like Rosine’s Bill Monroe, Lexington’s J.D. Crowe and Cordell’s Ricky Skaggs, but many lavish luthiers as well, whether it be Russell Springs’ Frank Neat, who’s built custom banjos for the likes of Earl Scruggs to the aforementioned Crowe and “Call Of The Wildman” personality Neal James; Caneyville’s Bryan England, whose mandolins and guitars have been used by country superstars George Strait and Brooks & Dunn; and Menifee County’s Neil Kendrick, who has been building guitars for over 20 years for the likes of Josh Williams of Rhonda Vincent and the Rage and others after being taught the trade by the late Homer Ledford.

Following in those rich footsteps of Kentucky-bred instrument makers is Ben Mason, an up-and-coming craftsman of violins and violas based in Lexington who is among the next crop of young luthiers set to carry the torch and build on the legacy of the state’s bluegrass heritage.

Born in 1991 in Lexington and moving to Fairfax, Virginia when he was seven, Mason recalls music being a constant within his family, with jam sessions around his grandparents pool a regularity growing up. While his dad could often be found strumming away on a guitar and his brothers blaring away on the boisterous brass of a sax and trumpet, Ben first was drawn to the cello, which he began taking lessons on shortly after his family relocated to the Old Dominion State.

Aside from his immediate family, which is chock-full of musical talent, one of Mason’s biggest musical inspirations and mentors has been Ellen Troyer, his first cousin once removed and a world-renowned violinist who holds a Bachelor’s and Master of Music degrees from the Juilliard School of Music that has been a part of the first violin section of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra since just prior to Mason’s birth. While in his youth Mason remembers being fascinated by Troyer both on and off the stage, enjoying talking about the intricacies of an instrument with her just as much as he enjoyed watching her perform under the bright lights. Due to Troyer’s connections, Mason also recollects having the opportunity to see big name acts like Yo-Yo Ma up close, occasionally getting to even go backstage to meet them.

“Having that source of inspiration was a huge influence at my young age,” said Mason. “I always loved taking my instruments to [Troyer] and having her tell me everything about its history and quirks.”

“Ben’s brothers chose brass instruments, so when he picked up the cello I felt a bit of an affinity for him because ‘Oh my gosh he chose a stringed instrument! Maybe I did have some influence on him,’” joked Troyer.

Troyer’s accomplishments also inspired Mason to pursue orchestra, which he participated in from elementary school to high school prior to his family moving back to Lexington. At the same time, Mason began to realize his natural ability to run fast, leading him to set his musical ambitions on the back-burner temporarily to participate in track & field competitions. While attending high school Mason was regarded as one of the top runners in Kentucky, earning him a walk-on opportunity to run for the University of Kentucky, where he twice had the chance to run in front of 40,000 people at the Penn Relays, the country’s oldest and largest Track and Field competition held annually on the University of Pennsylvania campus in Philadelphia since 1895.

Upon his graduation from college, where he finished with a Bachelor’s degree in Integrated Strategic Communications and a minor in Art Studios, Mason began to turn his focus away from running and back to music and how he could merge his love for playing with his love for working with his hands to build things. Still contemplating his next move, Mason was spurred to go all-in on building after an encounter with Brian and Will Skarstad of Skarstad Violins made through a mutual friend that Mason made while working at a summer camp in New Hampshire in 2014. Soon thereafter Mason ran into the Skarstads not far from their Brooklyn, New York headquarters, with Brian recommending he set his sights westward to the Violin Making School of America in Salt Lake City, Utah—the same place he received his formal training—for Mason to earn his.

Moving to Utah in July of 2015, Mason quickly settled in and enrolled in classes the ensuing month. During his first year of what is typically a three year program, Mason built two violins, all the while absorbing information like a sponge. Then, tight on money, Mason opted to leave the program, using the little remaining funds he had saved to purchase the tools necessary to begin building on his own while, for the time being, remaining in Salt Lake City, where he worked on projects with and for friends while also calculating his next career move, ultimately opting to move back to Kentucky in 2018.

“It was a matter of not knowing how much you miss something or somewhere until you’re away from it,” said Mason. “It was also at a time when Kentucky artists like Chris Stapleton, Sturgill Simpson and Tyler Childers were exploding in popularity, so I wanted to come back to see how I could potentially help contribute to some of the awesome music and creativity coming from my home state.”

After returning to Lexington, Mason moved through several short-lived workshop spaces including a temporary set-up in the bedroom of his apartment before discovering the Kre8Now Makerspace, a membership-based community workshop, renting out space there and moving his workshop within the building only a few of months after being back. In addition to having the space to work on instruments and store his gouges, chisels, knives, rosin salves and other tools Mason is also able to make use of tools within the Makerspace that he’d normally not have access to otherwise like CNC routers used to cut and design instrument molds and band saws to make quick, precise cuts.

“I jumped at the chance of relocating to within the Makerspace, not just because I could have my own personal workshop space there but also because of all the tools I’d have access to there that I can’t afford on my own,” said Mason. “I’ve also enjoyed being able to network with the other makers that utilize the space and absorb some of their knowledge to learn new skills and ways to troubleshoot curveball scenarios that occasionally come up in the building process.”

In his workshop Mason enjoys further exploring the intricacies of various violin types and makers as he crafts works made in a myriad of styles including the well-known Antonio Stradivari and Giuseppe Guarneri along with more obscure makers of the time such as Giovanni Battista Guadagnini, who spent time building and travelling between four northern Italy cities during his lifetime, with each violin built having sharing characteristics similar to the specific city it was crafted in, and Matteo Goffriller, a Venice-based builder and founder of the “Venetian School” of luthiers.

For his builds Mason prefers using European Spruce (Picea Abies) for the tops and European Maple (Acer Pseudoplatanus) for the backs, sides and neck, with all of the wood used typically aged for 20 to 60 years, which he either gets shipped in, buys up at nearby estate sales of makers who’ve passed on or off of leads from fellow builders. Mason also has a preference for nicely figured one-piece maple backs and old spruce tops, sometimes with bear claw figure, in addition to meticulously monitoring the density, weight and feel of the wood as he works it down to its final shape in order for it to have the desired tone of his client.

One of the most time-consuming traits of Mason’s builds making them stand out are the wood purfling that he inserts along the edges of his instruments that at first glance appear to be drawn-on lines but are actually from a small channel carved out of the existing wood by hand and replaced by three pieces of laminated wood that are bent and cut precisely to fit inside.

“While it can be one of the more frustrating parts of a building process for me, adding the purfling is also the most worthwhile and satisfying part as well due to the hyper-focused attention and focus it takes to complete correctly,” said Mason.

However, prior to carving and gouging into wood Mason turns to his personal computer, another piece of technology not around during the time of the builders that he so loves to study, to begin his own projects. In particular Mason utilizes Adobe Illustrator to draw up mock designs and measurements for his eventual builds before sending them off to the Makerspace’s CNC router to create an accurate inside mold.

In total an entire build usually takes Mason two or three months to complete, or 200-300 hours, with the craftsman also working full-time at Old Town Violins in Lexington focusing on instrument repairs, practically living inside his workshop at times when he’s not at his day job. It was also at his day job where Mason first met Jesse Wells, a professor at Morehead State University’s Kentucky Center for Traditional Music since 2001 and fiddler in fellow Kentuckian Tyler Childers’ touring band The Food Stamps, who has had him service a couple of his personal fiddles that needed repair.

“Ben has a great eye for classic violin and fiddle builds while also looking toward the future for better ways to meet the player’s needs,” said Wells. “He’s quite the fine builder for a young man still new to and working on his craft. His instruments have a very distinct tone from the first note struck and his construction and finishing work is top notch. However, where Ben truly excels is with his attention to the finer details of building and it really shows in the work he’s produced, which gets better and better with each build.”

The knowledge from working on repairs has helped to give Mason valuable insight into how to tackle the problems he encounters on his own builds, which more often than not have come when he’s been applying the instrument’s varnish (although he has cracked the ribs out of a violin or two as well). Nevertheless, Mason has learned to adapt to his errors and not let them get in his head and in the way of his creative process, instead of using them as a lesson of sorts.

“I’ve learned to keep my inner critic in check through building, which is something I’ve found to be useful in all walks of life,” said Mason. “It’s been a very humbling process because initially I’d get pretty upset with myself after making a mistake. It took some time for me to get to the point where I could have a more relaxed approach throughout the process, embracing my mistakes and learning from them rather than letting the frustration from the error get to me and chip away at my confidence.”

The month-long varnishing process is preceded by Mason brewing a resin salve on site by slow-cooking pine rosin on a hot plate for up to three weeks and adding coloring in a very precise manner, the chemistry of which he describes as being an entirely different discipline than the hands-on building that he’s accustomed to.

Once the varnish is applied, Mason has rigged up a ultraviolet (UV) light cabinet for his instruments to hang and dry in that is converted from an old networking cabinet once housing servers and other computer equipment that had been doing nothing but collecting dust inside the Makerspace prior to him repurposing it. The cabinet is wired up with UV lights, fans and a mirror globe motor that spins instruments around so they dry evenly, with space to fit one cello or three violins inside at once.

Since moving back to Lexington in 2018 Mason has built a total of three violins and one viola for clients, two of which, Carlie Geyer and Wyatt McCarty, are currently studying music at nearby Eastern Kentucky University in Richmond, Ky., along with their instructor Sila Darville, an assistant professor in violin and viola.

When asked about the difference between building for a classical player versus a bluegrass fiddler, Mason said, “I’ve thought a lot about this since moving back to Kentucky. The first violin I sold here was actually to a talented young man being trained in both styles and competes in fiddle competitions. I have conversations about this with musicians on both sides and my goal is to make great sounding fiddles to accommodate either style, whether it’s on stage with a bluegrass band or with a full symphony.”

Regarding any variations in his approach to building, or setting up, a fiddle for a classical player versus a bluegrass fiddler, Mason said, “Structurally, there’s no difference in how a violin or fiddle is made but two common changes made in a fiddle setup would be a slightly flatter arc on the bridge for playing double or a set of steel core strings. There can also be subtle differences in sound preference where fiddle players may prefer a darker tone and classical performers may desire more power and focus to fill a concert hall without the amplification which fiddlers commonly use. I’ve made instruments that lean in either direction or have both qualities and a lot of it can depend on the chosen model. For example, Guarneri del Gesu inspired instruments are associated with a darker sound in contrast to the more refined sound of Antonio Stradivari-inspired violins, but it’s ultimately up to the preference and needs of the individual player.”

“Ben has a great potential as a maker and will surely make his name heard nationally and internationally in the near future,” said Darville. “His visual aesthetic, particularly the dark tone of the wood and varnish he uses, complements the beautifully rich and full sound of his instruments.

“When I first tried out one of Ben’s violins I was fully expecting it to sound like a cigar box from China, but I ended up being blown away with the quality and sound of it given that he’s just recently started at the trade and isn’t an established veteran,” said Troyer. The biggest thing that surprised me about his violins is the ease of playing them and how old they feel when you go to pick them up despite their new-ness. The instrument’s sound speaks instantly and profoundly when you put the bow to it’s strings.”

Moving forward, Mason hopes to start making cellos in the future, an “ultimate” goal of his since that’s the instrument he primarily grew up playing before putting it down to run track. Additionally, Mason also occasionally builds ukuleles with scrap wood from his various other projects as a break from making violins, a side hobby which he is planning to expand on soon with a collaboration with fellow Makerspace member Stephanie Fan, a maker and commissioner of wooden goods and games incorporating the use of resin through local markets and her Etsy Store Atlas+Lily, to co-host a ukulele building workshop within the Makerspace.

Mason is also pondering launching another separate workshop on teaching people how to get started using chisels, saws, gouges and other hand tools, which he sees as a small way of giving back to the direct community within the Kre8Now Makerspace for all the new skills that he’s learned since becoming a member there as well as the larger community of Lexington and Central Kentucky.

“I really enjoy what I’m doing right now with the violin family of instruments,” said Mason. “There’s just so much to learn and discover about different makers and time periods that I don’t see myself getting bored or running out of ideas anytime soon.”