Home > Articles > The Archives > Ben Eldridge—Getting That Magic Feeling

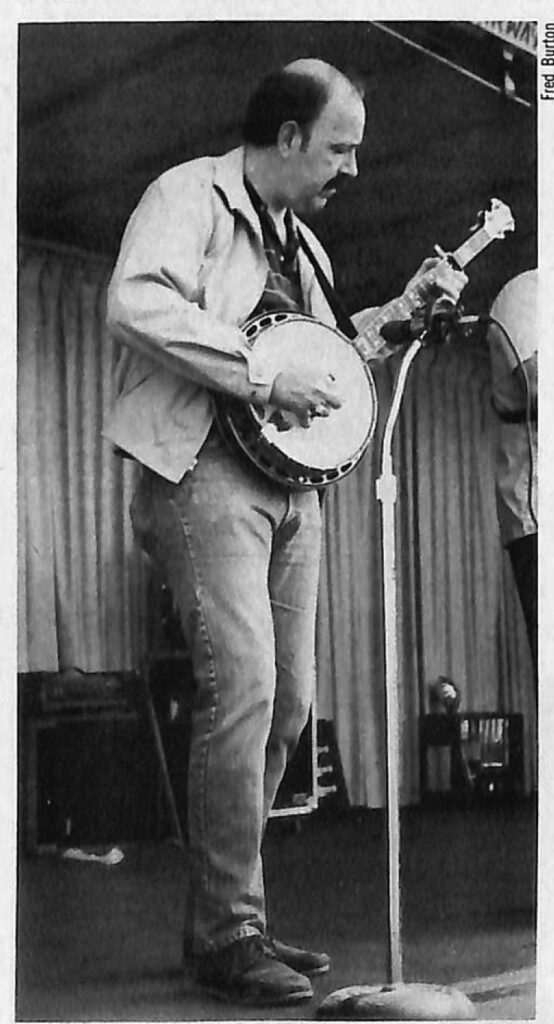

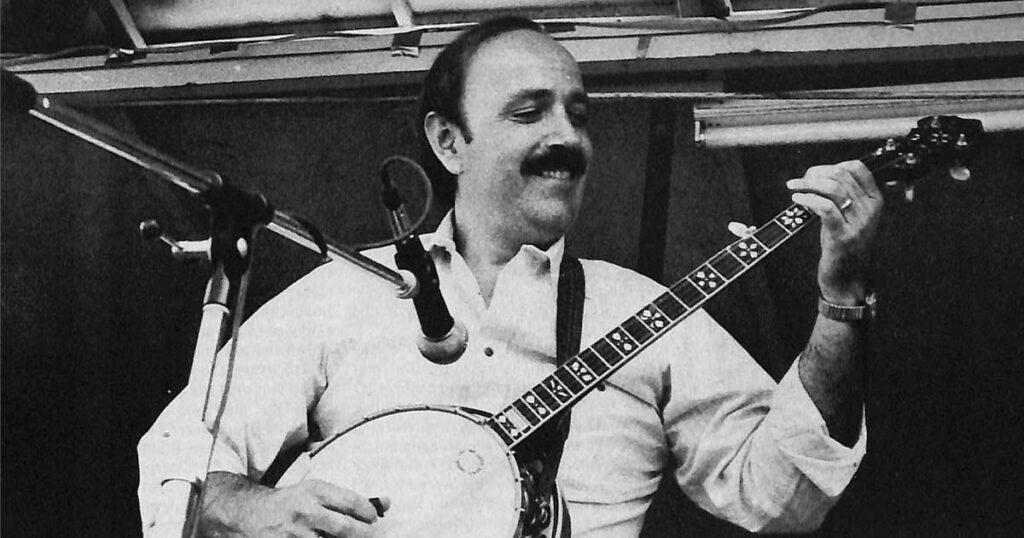

Ben Eldridge—Getting That Magic Feeling

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

February 1985, Volume 19, Number 8

Ben Eldridge is not your “typical” banjo picker. He is not from the hills of Tennessee, did not quit high school to go on the road with Jimmy Martin, has not written a banjo instruction book, did not join a family band at the age of five —in fact, he did not even grow up listening to Bill Monroe every Saturday night on the Grand Ole Opry. Yet, in many ways he is the picker we would all like to be. He can play in just about any style from the driving traditional sound to dazzling melodic licks, and still sound like Ben Eldridge. The music seems to flow out effortlessly, spontaneously, unobtrusively, and in all of the right places. The key appears to be Ben’s philosophy of being himself, not trying to force his picking, and playing from the heart rather than from the head. He just naturally seems to have an intuitive feel for music.

Music has been important to Ben for as long as he can remember. One of his earliest and most vivid memories from childhood is that of listening to a cousin who lived down the street play the harmonica. “Mike was out there on the porch one night playing things like ‘Red River Valley’ on the harmonica —and it just freaked me out. I can remember standing up there and listening with my eyes wide open and yelling, ‘Don’t stop! Don’t stop!’ I think that is the first time I ever remember getting that kind of magic feeling from listening to music.”

Though no one in Ben’s immediate family was particularly musically oriented, his own interest continued to grow and become focused on country music. While youngsters growing up in the hills of Appalachia were tuning in the Grand Ole Opry every Saturday night, Ben was becoming a devoted follower of the Old Dominion Barn Dance in his hometown of Richmond, Virginia. “It was a whole lot easier to get WRVA on the radio than it was WSM. I used to get my mother to take me down there about once a month when I was nine and ten years old, to the Lyric Theater. I think she hated it, but I used to love it. They had some great acts on there—Looney Luke and Roly Poly Reed, Crazy Joe Maphis, Grandpa Jones, Benny Kissinger and Curly Collins, and of course Sunshine Sue hosted the thing; and they did have some bluegrass acts like the Stanleys, Flatt & Scruggs and Mac Wiseman.

“The Carter Sisters lived up the street from us when they were on the Barn Dance—Helen, June, Anita and Mother Maybelle. We would see them driving through the neighborhood in a big black Cadillac. Maurice Duling and I got to know them—they thought we were cute little boys—and they would have watermelon feasts out in the yard for us. June was especially nice to us. I would get to go back stage occasionally at the Barn Dance. My mother would have to take me around after the show and I’d go knock on the door and say, ‘I wanta see June’.”

His exposure to the music through the Barn Dance inspired Ben to learn to play the guitar at the age of ten. “I really got hooked on the bluegrass sound from listening to Mac Wiseman. Before I even thought about playing the banjo, I heard ‘I’ll Still Write Your Name in the Sand,’ and he was playing all those neat runs on the guitar, and I thought that was the greatest thing since sliced bread.”

At sixteen Ben got his first banjo, and soon formed a band with some of his high school buddies, inspired by the mid-fifties sound of Flatt & Scruggs. “Lester and Earl were on the Barn Dance for about six months, about the time I first got my banjo. They had a live show from the studio at 11:00 and I would go down and watch them play. During that time between ’54 and ’56 they had a lot of bluegrass acts on the Barn Dance.”

Ben recalls, however, that he never was aware at that time of bluegrass as a separate art form. “I just thought it was Flatt & Scruggs and banjo music and didn’t have any electric guitars—that was the main thing that I liked—no electric sound. I was a real unsophisticated bluegrass listener. Where I came from you were a freak if you liked bluegrass music. There were very few people in Richmond who knew anything about it, not much of it was played on the radio, and I was too shy to call up the station and talk to the disk jockeys or anything like that. WXGI in Richmond did have a show back when I was a senior in high school, of a half hour of bluegrass, and that was the first time I heard the term ‘bluegrass.’”

In 1957 Ben left Richmond to study math at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. There he met guitarist/banjo picker Paul Craft, who began his musical career picking banjo with Jimmy Martin and has since become one of country and bluegrass music’s finest songwriters. The two of them sharpened their skills through countless picking parties during the next four years. In 1961 Ben moved to the Washington, D.C. area and began working at Johns Hopkins University in the Applied Physics Laboratory.

He soon got to know some of the other pickers in the area. He first met Dobroist Mike Auldridge and his brother Dave in 1963 at a party, and soon after their paths began to cross frequently. “I used to run into Mike occasionally out at the University of Maryland. I did some graduate work out there when he was an undergraduate. Also we’d run into each other over at (instrument builder/repair- man) Tom Morgan’s basement. I was over there a lot because I helped him refinish the neck for a banjo that I got from him, and Mike would come over there to have him do some work on his Dobro.

“John Starling moved to Washington in 1967 after he finished medical school. He and Mike and Dave Auldridge and Gary Henderson (now a DJ at WAMU radio) and a fellow named Bruce Barnes and I used to get together every Monday or Tuesday night down in my basement and pick. I’ve got some tapes that we made back then—some of them are not too bad. Gary’s played some of them on the air.”

In July of 1970 Ben joined Cliff Waldron and the New Shades of Grass, his first professional picking job. Mike and Dave Auldridge were also members of the band (on Dobro/baritone vocals and mandolin/tenor vocals respectively). During Ben’s tenure the band recorded three albums for Rebel Records (Rebel-1496, 1500, 1505). This band had much of the driving traditional sound, but, following the lead of the Country Gentlemen, was experimenting with different types of material not commonly associated with bluegrass, such as “Walk a Mile in My Shoes,” “Help Me Make It Through the Night,” and “Silver Wings.” This gave Ben a chance to begin experimenting with adapting his picking to different styles of music—a skill which has since become his forte.

But by the fall of 1971, the rigors of maintaining a “day job” (Ben works for a technical engineering firm called Tetra Tech) alongside a full performance schedule with the band became too much for both Ben and Mike Auldridge. “We were playing this ridiculous, tough schedule. We were playing two nights a week until 12:30-1:00 in the morning and then driving home for an hour and getting up and going to work the next morning—it was just taking its toll on everybody.” Both Ben and Mike left the band in September and went back to picking in the basement, “not really having any idea that we’d ever play again professionally.”

Several weeks later, however, Cliff Waldron, who had a regular Wednesday night “gig” at the Red Fox club, went to Nashville for the October DJ Convention and needed a replacement at the club. He called and asked if Ben and Mike could put together the old basement picking group and play the job. “So we got Dave and Mike, and Tom (Gray) playing the bass, and Bruce Barnes —[we] didn’t have (John) Duffey—and Starling and me and played the gig.” The night they were there, the owner of another club called wanting to get a bluegrass band to start a regular job in November. “We said, ‘Sure, we’ll do it, why not.’ So in the interim we called Duffey and asked him if he’d be interested —because we had played with him and we all knew him. And much to our surprise, he said ‘Sure.’ We got together a couple of times and practiced, but really, we didn’t know beans when we first hit the stage!”

The band (John Starling-guitar, John Duffey-mandolin, Mike Auldridge- Dobro, Tom Gray-bass, Ben-banjo) went back to the Red Fox after Christmas, as the Seldom Scene (a name coined by Country Gentleman Charlie Waller), and began regularly packing the house. A couple of months later, they were in the studio recording “Act I,” and in May they played their first festival, “scared to death the whole time!”

Now, twelve years and ten albums later, that bunch of basement pickers is one of the most successful bands in bluegrass. The name is not as appropriate as it once was —the Scene now carries a full schedule of festival, concert hall, and club performances the year round, from coast to coast. But what is remarkable is that the Seldom Scene has survived those twelve years with only one personnel change: John Starling left in 1977 to pursue his medical practice in Alabama and was replaced by Phil Rosenthal.

Ben feels that the band’s longevity is largely due to the independence of its members. The Scene flies as a group to some jobs that are long distance (such as Florida, California, or Iowa), but generally each member takes responsibility for getting to a show however he pleases. “We don’t feel like there’s this big ‘macho’ thing of everybody having to travel together on the bus. If somebody doesn’t like the fact that the other guys in the band smoke and it bothers them, that’s OK—if you want to drive by yourself, nobody gets their feelings hurt. If the other guys had to eat in the same restaurant that I like to eat in for eleven years, they’d be long gone. Can you imagine the five of us having to go everywhere together? It wouldn’t work. We’re just all too different.”

This attitude of flexibility seems to be what keeps the Seldom Scene’s demanding performance schedule from becoming a chore. The band members often take their wives and families along to festivals, so the trip is more like a family picnic than a job. This same easygoing attitude is carried into each performance. The Scene never programs a set ahead of time —they prefer the spontaneity of performing the material that they and their audience are in the mood to hear. This approach is successful because the band members are both excellent musicians and experienced professionals, who take their music (if not themselves) seriously.

From the beginning, the Seldom Scene has played music primarily because they enjoy it, and Ben, more than anyone personifies that attitude. Whether on stage or off, Ben quite simply loves to pick. Though he is a member of one of the top bands in the business, he can often be seen off “under a tree,” jamming with the “parking lot pickers” at a festival. And when the Scene is performing, Ben’s boyish grin as he discovers a new banjo lick, murmurs an aside to John Duffey, or, in a rare moment, steps up to a vocal microphone, make him an audience favorite.

Ben’s singing on stage is confined to two or three songs, and he does it mainly for the novelty effect. Though he loved to sing as a child, he now claims to hate it because, “I’m too dumb to remember words.” But when pressed he admits, “Actually I don’t mind singing, but I just have never been a very good bluegrass singer. I can sing Irish ballads and stuff like that. To me, though, it’s just a whole lot more fun to sit over in the corner and pick my banjo.”

Though Ben does not sing, he still takes an active part in band decisions about vocal arrangements, by being an objective listener and providing feedback and suggestions. Generally, he says, decisions about material and arrangements are made democratically. “Basically, we’ll get together and just start playing something, and see what it sounds like. Then somebody’ll have an idea and we’ll try it and if it works, it works, if it doesn’t… nobody gets their feelings hurt.”

Unlike many bands, Ben says that the Seldom Scene prefers to perform songs on stage before they record them. “I think that’s the ideal way to do it, first of all just to see what kind of audience reaction you’re going to get out of the song. And the more you play a song—especially in the group context —I think the more ideas come into your head, and you’re familiar with the song and you’re not fighting to remember the next chord.”

Ben also feels a need to have time to work with new songs in order to decide how he wants to play them. The process seems for the most part to be an intuitive one. “I have to kind of feel what’s going on. I can’t figure out what a break is going to sound like and then do it. I’ll just experiment with it, and when I get something I like, I’ll just know it. It’ll feel good and be easy to do. I may do things real crazy and people say I play funny and what I do is hard —well, to me it’s real easy. I just do the easiest thing for me.”

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

I grew up a teenager in the 70’s and listening to the Seldom Scene. My father listen to Flatt and Scruggs and Bill Monroe and I was well aware of bluegrass but when I heard the Scene I was hooked. I have since come to love and appreciate the pioneers of bluegrass, but the Scene was the reason I love bluegrass so much and love to play. Ben’s kick off on “Working on a Building” just blew me away. I love bluegrass but I miss the creativity the Scene had in their music. Miss Ben and the Scene. Thank you all for your music.