Home > Articles > The Tradition > Ben Eldridge

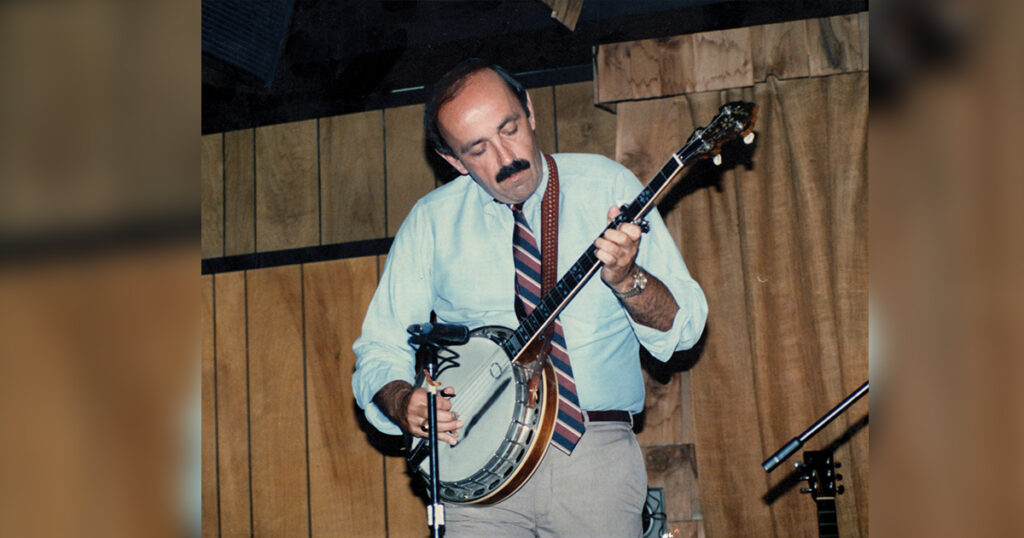

Ben Eldridge

Bluegrass Music Loses Another Banjo Legend

Photo by Dan Miller

Benjamin Rolfe “Ben” Eldridge (August 15, 1938 – April 14, 2024) was a co-founder of the Seldom Scene and served as the group’s banjoist and longest-tenured member; he logged a total of 44 years with the band from 1971 until 2015. As an instrumentalist in what is predominantly a vocal group, Eldridge was celebrated as much for his tasteful back-up work as he was for his inventive banjo solos. Of special note was his ability to seamlessly blend 3-finger Scruggs-style picking with flowing melodic passages.

As a youthful native of Richmond, Virginia, Ben gravitated towards country radio. His interest in what would later come to be known as bluegrass music was sparked when a local disc jockey used the Flatt & Scruggs recording of “Foggy Mountain Breakdown” as a theme song. Attendance at performances of the Old Dominion Barn Dance—the cast of which included luminaries such as Mac Wiseman, Mother Maybelle and the Carter Sisters, Flatt & Scruggs, Reno & Smiley, and the Stanley Brothers—further cemented Eldridge’s appreciation of the music. What really sealed the deal, though, was Mac Wiseman’s release of “I’ll Still Write Your Name in the Sand” which, oddly enough, featured two-finger banjo by Dave Akeman (aka Stringbean).

Eldridge’s musical development began at age 10 when he got a guitar. Six years later, on his 16th birthday, he got a 5-string banjo. Later in the year, he received a copy of a 45-rpm disc of “Dear Old Dixie” by Flatt & Scruggs. Ben learned to play the tune, note for note, by slowing the record down and carefully listening to it at 33 1/3-rpm. The tune wound up being his first public performance piece at a high school function.

After graduating from high school in 1957, Eldridge attended the University of Virginia where he studied Mathematics. Among his classmates was banjoist Paul Craft, who later toured and recorded with Jimmy Martin and enjoyed a successful career as a songwriter.

Following graduation from UVA, Eldridge accepted a position in the Applied Physics Laboratory at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. His proximity to the Washington, D.C., area put him in touch with local pickers such as Mike and Dave Auldridge. Soon he was hosting picking parties in his basement where attendees included future Seldom Scene vocalist John Starling and area disc jockey Gary Henderson.

Eldridge turned professional in 1970 when he joined Cliff Waldron’s New Shades of Grass. Other band members included his picking pals Mike and Dave Auldridge. This trio, with others, recorded three albums with Waldron: Right On!, Traveling Light, and the gospel Just a Closer Walk With Thee. Reviewer Bill Vernon noted in Muleskinner News that “Ben Eldridge is one of the under-discovered heroes of Blue Grass—in his own under-stated way, he weaves a tremendous variety of imaginative ideas through this LP, providing both perfect backup and flawless solo work.”

Sadly, the demands of touring with Waldron conflicted with Eldridge’s day job and after only a year with the New Shades of Grass, Ben was forced to return to amateur status. His retirement was short-lived. Waldron called on Eldridge and others to take his spot one weekend when he had a conflicting engagement. Those that gathered to sub for Waldron—John Duffey, John Starling, Mike and Dave Auldridge, Ben Eldridge and Tom Gray—liked what they heard playing together. So much so that they secured a weekly gig at the Red Fox Inn in Bethesda, Maryland, and, at Charlie Waller’s suggestion, christened themselves The Seldom Scene.

The new group secured a recording contract with Rebel Records and recorded a string of well-received, highly influential albums including Act I, Act II, Act III, Live at the Cellar Door—perhaps one of the all-time best-selling bluegrass albums—The New Seldom Scene Album and Baptizing. The band quickly became festival and concert favorites and did much to influence the course of bluegrass throughout the 1970s and 1980s. A key component to this success was Eldridge’s imaginative banjo work.

After seven years of steady weekly performances at the Red Fox, the Seldom Scene took up permanent residence at the Birchmere in nearby Alexandria, Virginia. Their long-standing Thursday night shows aided greatly in establishing the Birchmere as one of the premier music venues in the Washington area.

Eldridge appeared on 22 albums by the Seldom Scene. His recording resume, however, includes a total of at least 55 projects, on solo albums by his fellow band mates (Mike Auldridge, Phil Rosenthal, etc.), releases by autoharp guru Bryan Bowers, singer Suzanne Thomas and a highly acclaimed tribute to John Duffey called Epilogue.

In 2014, Eldridge and other members of the Original Seldom Scene, were inducted into the International Bluegrass Music Association’s Hall of Fame. The following year, on New Year’s Eve at the Birchmere, Ben performed his last show as a member of the group. Outlasting all of his former bandmates, the group at the time of his retirement included guitarist/lead singer Dudley Connell, mandolin player Lou Reid, bass player Ronnie Simpkins and Dobro player Fred Travers.

Although Eldridge never had a solo album of his own, in 2023 he did release a book entitled On Banjo – Recollections, Licks, and Solos by Ben Eldridge; Randy Barrett transcribed the solo arrangements of Ben’s playing.

The forward to Ben’s book is by fellow banjoist Bela Fleck. As an acknowledged master of his craft, Fleck is uniquely qualified to speak on Eldridge’s playing. “Ben is a real gift to the banjo world,” he writes. “Especially in an ensemble sense. His playing sounds so effortless it doesn’t occur to you that he’s playing a lot of brand-new stuff. The subtlety is everywhere, but Ben can also bang you on the head. His legendary playing on ‘Rider’ is wholly different. More than merely a hot solo, it’s a major redevelopment of the ‘chromatic banjo book,’ creating a new chapter of bluesy chromatic language which he uses throughout the song. It’s something evocative, expressive, creative-and it sets the stage for the world of modern banjo in the years to come.”

In a life that encompassed some 75 years of making music—some just learning, some just for fun and some professionally—Ben Eldridge and his music reached and touched a multitude of people. Many he knew well, some were just in passing, and some he never met at all. But his music, his gentle soul, and his humanity spoke to them all. Those qualities and more are reflected in an outpouring of tributes from a host of well-wishing friends and fans, including . . .

Jerry Douglas: Along with Tom Gray, Mike Auldridge, John Starling and John Duffey, Ben Eldridge was drafted into this super-band that changed a generation of bluegrass music. When I was 17 and playing with the Country Gentlemen, I used to get in my car in Springfield, Virginia, and drive the Beltway in D.C. around to The Red Fox in Bethesda. Back then you could make it in about 30 minutes. Ben was a hypnotic but driving banjo player. All cylinders firing but the notes were all interesting. A true innovator. One of the good guys. Loved by so many and the father of another great musician, Chris “Critter” Eldridge. You have my heart tonight.

Gena Britt: Ben Eldridge was one of the most innovative and expressive banjo players I’ve ever known! He was WAY ahead of his time. As a member of the original Seldom Scene, his impact was huge on bluegrass and the banjo world. I spent a lot of time around the Seldom Scene and he was always so kind to me! He called me “Samantha Shelor” because he said he heard so much of Sammy Shelor’s influence in my playing. I will miss him!

Tim Timberlake: Native Richmonder Ben Eldridge was so much more than one of bluegrass music’s most innovative and influential banjo masters. He was a good and gentle soul, proud father and loving husband. His still-thriving band opened so many ears like mine to a new world of bluegrass beyond Stanley and Monroe back in the 1970s. From the Rappahannock to Graves Mountain . . . such indelible memories of good times built around good music.

Phil Rosenthal: It was a privilege playing with Ben so many years in the Seldom Scene. So creative, and fun to be with. He had a positive vibe that came through in his music.

Ned Luberecki: Growing up and learning about bluegrass in the 1970s and 1980s in the Baltimore/Washington area, there was no bigger band than the Seldom Scene and Ben Eldridge’s banjo playing was such a major part of that sound. Ben’s style was bluesy and intricate. It seemed like his banjo was weaving its way in and around the vocals just perfectly. He was the ultimate “Team Player,” never hogging the spotlight (it would have been hard to wrestle that away from John Duffey!) but always looking for a way to enhance the song being played. I was proud to get to know him, if only just a little. I always looked forward to sharing a festival stage with the Scene so we’d have a chance to hang out and chat a bit. You were one of my favorites.

Mary Beth Aungier: Ben Eldridge was a gentle giant in the music industry and was so generous and kind to me always. I spent five years slugging beer at the Birchmere as a waitress and looked forward in joy to the Thursday night Seldom Scene gigs.

Dick Cataldi: For years my job took me to Washington, D.C., on Thursdays and I always went to the Birchmere. On one trip, my Bluegrass Unlimited arrived as I left home and I took it along. Evidently that issue had not been received in the D.C. area yet and the Seldom Scene was on the cover! During their intermission, Ben came over to my table and asked to take a look. I handed it to him and he gave me a wink. When they started the second set he brought it back to me with signatures from the band. We had a nice chat. Every time after that, when I was at their show, he came over to say hi. I’ll miss the man.

Darren Beachley: Ben Eldridge was always kind and hilarious. He was an innovative force in music, for sure. I first encountered Ben as a small child while he was working with Cliff Waldron with my uncle, Bill Poffenberger. I was only four, maybe five, but was drawn to music and Cliff’s sound, of which Ben was a HUGE part. Fast forward a few years when I began to pick, Ben would come out in the field and jam around a campfire. It was always a thrill to have him at a jam at Indian Springs or Gettysburg. Although he was known as a progressive banjo player, when he would jam it always sounded to me like he loved the Stanley Brothers. I was fortunate enough to be on some trips with Shawn Nycz when he was a member of the Scene’s crew. Conversations with Ben were always memorable. Thanks for contributing so much to the music and to my learning it.

Allen Shadd: I am thankful to have wonderful memories of Ben Eldridge and to have his music. Flashback—it was the summer between my junior and senior years of high school (1981) and I was on the road with Claire Lynch. We ended up playing a couple of festivals with the Seldom Scene, as well as a handful of shows around Virginia and Washington, D.C. I got to hang around those guys for a bit, and they treated this kid like he belonged. But I remember one conversation with Ben. He and I were discussing his playing on Tony Rice’s album California Autumn. Specifically, his break on “Bugle Call Rag.” One of his breaks was a pretty advanced lick, and he told me he worked so hard on it that he nailed it in the studio on like the second or third try. Then he spent the next two hours trying to play the simple “Bugle Call” chime and thought he would never get it. I will always remember how he laughed about it. I have often remembered that when I have struggled with musical passes that shouldn’t be so hard. Thank you, Ben.

Matt Hickman: Ben Eldridge was one of my favorite banjo players. He was such an innovative musician and was such a nice guy as well. He would sit and chat with me backstage at Gettysburg and he had no idea what a thrill he was giving this guy. Prayers to family.

Randy Barrett: As a young fellow I spent 1,000,000,000 hours in front of my record player, lifting and dropping the needle 1,000,000,000,000 times, trying to learn what Ben Eldridge had to say on the banjo. To say he had an impact on my playing is a vast understatement. It was an honor to work with him on his book, On Banjo. The old saying advises people not to meet their heroes unless they want to be disappointed. Not so with Ben. He was kind, patient and utterly modest. He left us an invaluable library of inspired banjo playing that will be studied for generations to come.