Home > Articles > The Artists > Béla Fleck

Béla Fleck

Goes Deep into his New 19-cut Album My Bluegrass Heart

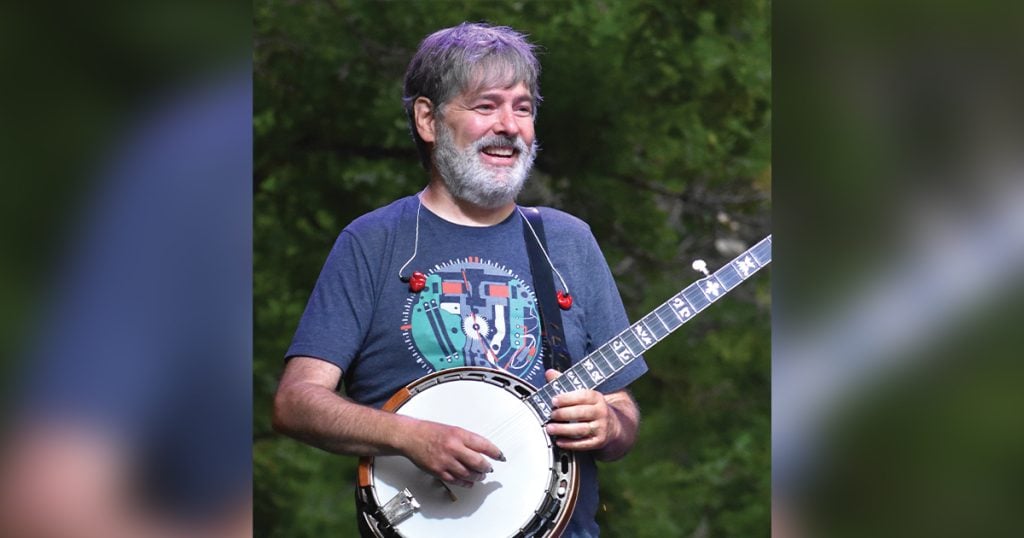

Photos by Kevin Slick

“I want the recording to sound like the musicians own that music, and not sound like they have just managed to get through it.”

It was a bittersweet occasion when the news broke that Béla Fleck had recorded a follow up to his previous two bluegrass solo albums Drive and Bluegrass Sessions. For most of us, the revelation came in the hours after Christmas Day 2020 when the music world was hit in the gut by the news that the legendary guitarist Tony Rice had left this world.

Many tributes to Rice appeared after the announcement of his death, including Fleck talking of his angst at having to record his new 19-cut album My Bluegrass Heart without his recently departed friend. Rice had appeared on those great Fleck albums recorded all of those years ago, yet Rice had put his guitar down for good in 2013.

So, Fleck decided to move forward with My Bluegrass Heart by bringing in some young gun musicians while also calling in some artists he has recorded with for decades. The end result is a fabulous, diverse and mesmerizing collection of original tunes for a new generation, and proof that Fleck’s creative juices are still going strong.

Before we get into this wonderful and exclusive interview that Fleck has given us here at Bluegrass Unlimited, it would be a good time to remind folks of what Fleck’s intentions were with this project.

As Fleck said in his initial PR for the recording, “This is not a straight bluegrass album, but it’s written for a bluegrass band. I like taking that instrumentation, and seeing what I can do with it—how I can stretch it, what I can take from what I’ve learned from other kinds of music, and what can apply for this combination of musicians, the very particularly ‘bluegrass’ idea of how music works, and what can be accomplished that might be unexpected, but still has deep connections to the origins.”

Fleck has been stretching the boundaries of bluegrass, newgrass and new acoustic music for decades, going back to his time with his early mentor Tony Trischka, who appears on this album, and his recordings with the always-boundary-pushing New Grass Revival four decades ago. And, he has done it while becoming one of the most accomplished musicians in the history of the genre.

On My Bluegrass Heart, Fleck was inspired to record in a different way. Usually, in the past, he brought together a core group of musicians and stuck with them throughout the studio process, bearing down on a vision. Here, due to a longing to record with old buddies as well as a desire to record with younger artists, Fleck has created a sprawling, fresh-sounding and open-minded effort with 20 collaborators that was well worth the wait.

The musicians on My Bluegrass Heart include Jerry Douglas, Sam Bush, Edgar Meyer, Stuart Duncan, Bryan Sutton, Sierra Hull, Billy Strings, Chris Thile, Billy Contreras, Michael Cleveland, Molly Tuttle, Mark Schatz, Cody Kilby, Tony Trischka, David Grisman, Dominick Leslie, Paul Kowert, Royal G Masat, Noam Pikelny and Andy Leftwich.

The first cut on My Bluegrass Heart is a romp called “Vertigo,” featuring Bush, Duncan, Meyer and Sutton. This upbeat opener proves right away that Fleck can still write a tune that is both challenging and fun.

“I wrote ‘Vertigo’ about three or four years ago,” said Fleck. “I started writing it when I was about to do a tour with Chick Corea and his Elektric Band and the Flecktones and I wanted to write something that we could all do on the encore. I knew I had something, but I didn’t really complete it in time for Chick, but I did complete it in time to teach it to Sam and all of the guys that played on it for a Telluride Bluegrass Festival show. I think there are some Indian rhythms in there. Everybody is confused by the time signature, but it is all in 4/4, it’s just divided funny. The way the song starts, we kind of speed up into it, which leaves people even more confused as to what it is. But then, I love the way it lands as suddenly, once it is in the groove; it’s in the groove. Every time from then on, it’s pretty easy. If you keep counting 1-2-3-4 through the bridge, it will come out on the 1 in the end. I like stuff like that. It’s deceptive. It’s actually about syncopation. It’s not time signatures; it’s a syncopated 4/4.”

And that, my friends, is an excellent description of how cool-yet-complicated-yet-fun music can be in the right hands. Bluegrass, even in its most basic form, can be intricate and crooked while being free-flowing and upbeat. Bluegrass is also a challenging music that can take on and handle high-end influences from other genres, as Fleck has proved throughout his career, and that is a fascinating and good thing.

Billy Strings is one of the four guitarists that Fleck brought in for this project, with the other three being Molly Tuttle, Cody Kilby and Bryan Sutton. Sutton, of course, has been playing Fleck’s music for a long time now, especially as a yearly member of the Telluride House Band.

Strings has rocked the bluegrass world in recent years with his sold-out, big arena shows and his knack for turning a new generation onto the music of Doc Watson and the Stanley Brothers while staying exploratory and modern. Here, on My Bluegrass Heart, Fleck puts him to the test. Playing on six cuts, Strings proves that he can keep up with his idols and then some.

“A little bit,” said Fleck, when asked if Strings was a bit wide-eyed when coming into these sessions. “But, he’s a badass. He has every right to play with anybody he wants to, so I was pretty thrilled that he would do it, considering how busy he was getting. We had just met. We were just getting to know each other. We met at a festival in Virginia in a parking lot at a hotel. I saw him and I yelled down from my hotel room where I was practicing and he was loading his van. I said, ‘Hey, is that you, Billy?’ He says, ‘Yeah.’ “It’s Béla up here.’ ‘Hey, I wanted to meet you.’ I came down stairs and we stood around in the parking lot for a little while and he was so nice. He cared about what I do and that made me feel good, so I asked him if he wanted to get together and play a little bit and he came over.”

For Strings, although he has now jammed with multitudes of great pickers by this point, that was the invite of a lifetime.

“Billy and I had a late-night jam after the kids went asleep, in the back of the house where they couldn’t hear it, and he was on fire,” said Fleck. “He was so good. I thought, ‘Wow, we need to get this guy on this record if he wants to do it,’ and he did. He really enjoyed being there with Sam and Jerry and Stuart as I don’t think he had ever done that before.”

Soon, Strings would be recording some demanding and energizing cuts on this album such as “Charm School” and “Slippery Eel.”

“I was thinking there ought to be stuff on this record that is pretty close to the center of what bluegrass is, and then there ought to be some stuff that is way out to the edge, and this record should have all of that,” said Fleck. “It would then reflect who I am as I love all of those things. So, on the straighter side you have a tune like ‘Boulderdash’ that could almost be a Don Reno tune, in my opinion, or something like ‘Wheels Up,’ which could be a Bill Keith bluegrass-type of tune. Those cuts are fairly inside. Then, you’ve got ‘Charm School,’ which is way out on the edge. I figured that if Chris Thile was going to come in and he and Billy were going to play together for the first time; they can handle some pretty complicated stuff and it would make a nice contrast for the other things on the record. As it turned out, they came in and we had an amazing session when we recorded those tunes and we had a blast. It was a like-mind, you know, as everyone was game to try something hard and set a high bar, and we got there.”

And so, the question comes to mind from us mere mortals—When you challenge other musicians with something hard to play, do you send them a demo first?

“Yeah, I sent them all the music ahead of time,” said Fleck. “In fact, Chris was the only one not in Nashville. Everyone else was here so I was able to rehearse with the other musicians and make sure they knew it so that Chris was able to walk into it and we figured out the arrangements together. Because, we only had that one day (to record with Thile) and Chris was flying in that morning from somewhere, and we had all of the mics ready to go. So, everybody sat down and we just started doing takes. Chris was prepared. He’s got this photographic memory, anyway, and he knew just what to do. Then, after everyone left after a long, hard day, Chris and I cut another track starting about midnight and by 3 or 4-in-the-morning we had recorded that duet called ‘Psalm 136.’ That worked out pretty great.”

The song “This Old Road” is another cut that falls into the straight-ahead bluegrass category, albeit deceptively, as Fleck puts it. The best way to describe it is it sounds like a traditional bluegrass song that you listened to while lying on the grass on a sunny day and staring up at the clouds, not realizing that you have nodded out and in the middle of a daydream. It’s like a bluegrass song if you heard it on a merry-go-round at an amusement park. The melody is there, yet there is enough space in the tune where your mind can fill in the blanks. That admittedly all sounds wack, yet cue it up and you’ll see what I mean.

“Yeah, that song is a little bit deceptive as it feels really normal and then you’ll hear some chords that you wouldn’t hear that often in bluegrass, that are a little bit jazzy and a little bit dissonant,” said Fleck. “But, it has that warmth and that bluegrass feel. I think that a lot of times when my music gets a little bit more progressive, I’m still trying to keep that feel. Maybe there is more harmonic stuff going on, maybe there is more rhythms going on, but I still want it to have that same feel that Tony Rice would play with or J. D. Crowe and the New South. I want to have that ‘Manzanita’ feel, which is what I call it. That holds it all together. That makes it just so much more palatable for people because if you can’t relate to some of the stuff we’re doing, the rhythm is sort of hard to deny. I put a lot of stock into getting takes with great rhythm and recording with players that can play that kind of time. That to me is a crucial element. If it doesn’t have that, I’m not that interested in doing it.”

I bring up the fact that for over a half of a century now, there have been jazz musicians talking about how The Beatles were not that good as musicians, yet these same jazz musicians have recorded countless tracks featuring Beatles’ melodies. Fleck responds.

“I think there are different kinds of musicianship,” said Fleck. “There is virtuosity and instrumental ability, and then there is overview musicianship, where someone understands how music needs to work together or what makes a great song or what makes a great recording. And, those are not the same talents. They are all different kinds of talents. That is what makes a great band so good, because when you have a band that has different talents and it all comes together; you get a real nice mixture of strength. So, I think it is a mistake to dismiss anybody whose talents are different than your own.”

Another key when it comes to learning challenging music or improvisation, according to Fleck, is the anticipation of the chord changes happening underneath.

“Some of the training we get when we do study jazz or improvising is how to get through chord changes,” said Fleck. “Sometimes it is nice to look at them on paper and sort of imagine what is coming next. Sometimes it is great to memorize them and get them into your system. I like to play over those changes a lot before I record. I might make a recording of just the hard part that I’m going to be soloing over and play over it for an hour, working on it until I can anticipate the chords coming as if I have played it for ten years. Because, I want the recording to sound like the musicians own that music, and not sound like they have just managed to get through it. So, for me, I start with myself to make sure I am ready. I make little cheat tracks to play along with and I play with a metronome a lot. Whatever it takes, I’m willing to work hard. I enjoy working hard and I like seeing myself make progress because it keeps me from becoming complacent or stuck as a musician. I like to have projects that I’m working on that I can barely do.”

Still, at the heart of good music, complicated or not, are good melodies. The tune “Hug Point” on My Bluegrass Heart is a great example of a sweet melody. Suddenly, for some reason, it pops into my head to ask Fleck if recording and playing music with his accomplished wife Abigail Washburn has influenced his approach to melodies, and the response is positive.

“I think Abigail influences my ability to appreciate a good melody when I write one, and not dismiss it,” said Fleck. “She might say, ‘Well, I like that tune. Why don’t you do that tune that I heard you play on the banjo? It sounds really nice.’ I’m like, ‘Oh, that thing? It’s so simple.’ And she is like, ‘Yeah! It’s so simple.’ I care about what she thinks, so she is a great influence in my musicianship because she cares about the heart and soul whereas I might be more technically-minded when it comes to my musical consciousness. She points me to the parts of myself that are a little bit more human and warm. But, I like it all. I like real technical music. I love crazy jazz and avant-garde music and modern classical music, and music from different countries that I can’t count and don’t understand. I love all of that stuff, but I also love music that hits you deep in the chest. So, it’s good to have somebody that will point to parts of yourself that you might be letting go.”

Not only is Washburn excellent at finding and creating melodies when it comes to her own music, she also often plays the cello banjo, the bigger and deeper-sounding instrument that some call the moon banjo. Fleck picks one up for the beautiful cut “Hunky Dory,” which features Stuart Duncan on fiddle, Jerry Douglas on resonator guitar, David Grisman on mandolin, both Edgar Meyer and Mark Schatz on bass and Tony Trischka on regular banjo.

“I think she got a cello banjo first, and it’s nice as I love to get down there in that range,” said Fleck. “I usually spend my time in the alto range and I’m always in that portion of the frequency spread in my brain when I play. But all of a sudden, with the cello banjo, I’m an octave lower and it feels so good. I love playing that instrument with Abigail where I can be the bass and get down into that range and be creative in a different way. In the case of ‘Hunky Dory,’ I had written a tune that very much reminded me of John Hartford. I had a pile of fiddle tunes that I had written that I couldn’t get on the record. I just didn’t have the room. So, that is what ‘Hunky Dory’ is, kind of a whole set of those fiddle tunes strung back-to-back. I was thinking, ‘How can I get these fiddle tunes onto the record so that I can get them out there and get them out of my system so I can write new stuff, without having to go in and record each one?’ John Hartford has been gone for 20 years now, yet his unique personality and music still inspires.

“That is when I came up with this idea of stringing them back-to-back while having different musicians come and go while I played the cello banjo,” said Fleck. “I thought that would be something that John Hartford would really like, and there is something about some of those tunes that remind me a lot of him, too. It’s really fun because it starts out with the cello banjo playing a melody, then the Dobro comes in and then it disappears, then the mandolin comes in and it disappears, then the fiddle comes in and then it disappears, then the bass comes in and it disappears, and then everybody comes in at the end. Everything about it is perfectly traditional as far as fiddle tune music, but it was just a different way to present it. I loved knowing John Hartford. He was very sweet to me.”

Washburn was a positive influence on this project in yet another way, when she pointed out that Fleck had no female artists on this recording. That suggestion made perfect sense as Fleck produced an album for Sierra Hull not long ago. So he brought in Hull and the amazing guitarist Molly Tuttle.

“I didn’t know that much about Molly, but I heard her at the IBMA Week for the first time and I thought, ‘Wow, she’s really got some kind of a presence,’” said Fleck. “And, it wasn’t just that she was a good guitar player or singer, it was that you wanted to hear her. You wanted to hear what she was going to say next, or what she was going to sing or play next. There is something very vulnerable about her as well. And, I loved it. A few years ago, I was looking to put something together for a show and I had an idea of inviting her and Sierra to get together and play with me, and they came over and I found out how good she was in person. I was really interested in hearing the two of them together as a duo. But, we didn’t get to do that gig, it turned out, so I was looking for another chance to play with Molly. With Sierra, I knew her a lot better from producing her album Weighted Mind.” Hull’s album Weighted Mind, produced by Fleck, garnered a Grammy Award nomination in 2016.

“Sierra is such a good person and as talented as anybody on the planet,” said Fleck. “We had never collaborated on my music and I had never thought about it. Then, Abigail tapped me on the shoulder later into the album after I put all of these great groups together and she said, ‘There’s no women on here.’ I said, ‘Wow, you know what?’ There is some unconscious bias that I didn’t realize I had, as I was pursuing people I knew and liked and was interested in and that didn’t cross my brain. But once it did, I was like, ‘Well of course,’ and then Sierra and Molly came in and kicked holy you-know-what. They were really good, and just as good as anyone else on the album, which is probably a demeaning thing to say because—why wouldn’t they be that good?”

Going counter to the prevailing way of recording music these days, as in folks recording their parts elsewhere or at home and then sending it in, Fleck insisted that all of the musicians who were playing on this project show up in person. The pandemic, of course, has exacerbated that previous approach to session work, but My Bluegrass Heart was recorded and finished before the covid virus hit.

On cuts like “My Little Secret,” we once again get to hear the acclaimed classical musician Edgar Meyer solo with his bow on an acoustic bass on a newgrass tune, a beautiful and intriguing sound that was heard often back in the Strength In Numbers days.

With this recording being the third part of Fleck’s unofficial trilogy of albums exploring his original views of bluegrass and newgrass music, and considering the 20 years that went by between those albums; there is one looming question that comes to mind. On Fleck’s landmark album Drive, the tune “Whitewater” became an instant instrumental classic in the bluegrass canon.

So, was there any “Whitewater” pressure when it came to writing tunes for this new project?

“I didn’t feel that, although I think ‘Wheels Up’ is the closest to that, and that tune was almost an afterthought,” said Fleck. “What happens is I say, ‘I’m going to make a bluegrass record,’ and then I start thinking about the possibilities musically and sometimes I am more intrigued by things that I haven’t done yet. I’m looking for, ‘What can make this different from everything else?’ So, I didn’t feel any ‘Whitewater’ pressure, but I also knew I had ‘Boulderdash’ and in the end I had ‘Wheels Up,’ and those are a couple of pretty strong straight-up tunes. (As for ‘Whitewater’ becoming a standard), I love it. It’s a great feeling that people love it so much. I loved the experience of playing it live with Tony Rice many, many times, but the recording of that tune was an amazing moment. It was the first take on that album.”

I mention to Fleck a conversation I had with Jerry Douglas not long ago. All of us are in our 60s, and Douglas told me that he could no longer just roll out of bed, pick up his axe and play “Whitewater,” that he had to warm up to it first due to getting older. In the same light, I ask Fleck about his level of dexterity after playing the banjo for many decades.

“I am 63 and one of the things that I noticed, especially when Grisman was here to play on the album, he said, ‘You know, I can do pretty much everything I could always do, but I can’t play as fast,’” said Fleck. “And I thought to myself, ‘Well, that’s too bad,’ yet I was sympathetic. Now, however, after the pandemic hit and not playing for almost a year and a half, hardly playing any gigs at all; I got out my banjo and tried to play this music and I couldn’t do it, either. My hands just wouldn’t go that fast. After playing with Michael Cleveland and Sierra Hull and Bryan Sutton, however, it came back. After four or five days of hitting it with those guys, it came back. So, now I think that at this age, I have to maintain it. I have to practice or it’s not going to happen.”

Fleck is amazed by the younger talent on this album, from the innovative skills of Paul Kowert and Dominick Leslie to the brilliance and gameness of guitarist Cody Kilby, from the high level of playing by Sierra Hull, Michael Cleveland and Molly Tuttle to calling Billy Contreras “a genius” on the fiddle. But, it also felt good to have his old buddies Sam, Stuart, Jerry, Edgar and Mark beside him in the studio again, with the absence of Tony Rice noticed and felt.

“When we were all there recording, there was another guitar player in the room, so in a way it is kind of like bad manners to say, ‘I wish Tony was here,’ especially when you have Billy Strings or Bryan Sutton doing wonderful things right there,” said Fleck. “Everyone has their own gifts. None of them have what Tony had, but Tony didn’t have what they have, either. There is something about the way Tony played that was so great for banjo players that it was addictive. If you could get Tony, you knew that you were going to play better. But, I had to get over that pre-conception for this album because I couldn’t get Tony.”

Fleck did think of a way to include Rice on this new release, but it just didn’t happen.

“I was going to ask Tony to write the liner notes because I wanted him to hear how great all of these guitar players did in his seat,” said Fleck. “But, he passed away before I could ask. And yes, I think there was some pressure on the other guitarists. I think they felt the moment, that this was Tony’s spot, especially when it was with Sam and Jerry and Stuart and me. I think they could feel it and they really wanted to deliver, not like Tony, but as themselves, playing in as great a way, and I think they did it. I really do.”