Home > Articles > The Archives > Band On The Run – The Johnson Mountain Boys

Band On The Run – The Johnson Mountain Boys

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

Volume 16, Number 6, December 1981

“Let the word go forth from this time and place, to friend and foe alike,

that the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans…

proud of our ancient heritage… ”

—President John F. Kennedy January 20,1961

On a crisp winter day when the fall leaves had turned to a dried brown matter and the snow had not yet arrived, a young mountain boy was filled with a child’s happiness on his 12th birthday.

“Poppa, whatcha gonna give me for my birthday?” the young boy asked in wonder as he sat on the pine-plank floor in front of a crackling fire.

His father answered from a nearby rocker, “If you really want to know. I’m going to give you something you can keep forever. It’s more valuable than a whittlin’ knife, or a sling-shot or even a thousand cats-eye marbles. But, I’ll only give it to you if you promise to pass it along to others so they, too, can enjoy it.”

The boy, not knowing what to expect from his father’s strange description, gazed with a look of bewilderment as he said, “I promise. Poppa. Tell me what it is. ”

The father arose and went into a bedroom. He came back with a six-string guitar whose varnish gleamed in the firelight like a beveled mirror darkened with age.

“If you play this right and learn from others, the riches of the past are yours. There’s lots of songbooks and records to draw from. And, if you become skilled enough in what you do, maybe you can create something beautiful for others in the future to enjoy. I give you, my son the gift of music.”

That somewhat fictional story was told because music truly has been a gift passed from generation to generation over thousands of years. Legend has it that the first song ever raised on this earth was Eve singing a lullaby to one of her two sons.

Songs echoed through the deep woods of America before it was so named as early Indian tribes gathered around campfires and sang ancient chants. Colonists from European nations and slaves brought from Africa carried to America their musical heritage; the gift being passed.

The Age of Recording caused the spread of music like a prairie fire on dry, western land whipped by high wind.

From the prisons where the lowest criminals are held to The White House residence of America’s First Family, the gift of music has been heard bringing comfort and joy to those who listen or sing.

As our country became involved in one foreign war after another, our soldiers carried our songs to foreign lands. Country music especially was affected as a result of soldiers being moved to military bases around the nation and as a result of civilians moving around looking for work.

Grand Ole Opry star Minnie Pearl once wrote about that transformation and noted in her letter, “I think the war did more to spread and further the popularity of country music than any other influence. World War II and the subsequent wars caused the military personnel to carry the love of country music literally all over the world. This was at a time when country music really needed to gain a foothold…The Opry was growing by leaps and bounds during the war years. We were being joined by new artists practically every month or two as the interest in country music grew. The crowds were large, in spite of rationing gas. We all performed at war bond rallies, outside on truck beds and inside wherever!

“We all rallied around the general cause. We sang patriotic songs and got into the spirit. Elton Britt’s “There’s A Star-Spangled Banner Waving Somewhere” was a huge hit. There were special celebrations wherever the acts were playing when victories were declared. Also that happened on the Opry,” Minnie related.

So, you readers may be asking by now, what does all of this have to do with the primary subject of this article. The Johnson Mountain Boys from Montgomery County, Maryland, near Washington, D.C.

It was this combination of music being passed down through the years and this migration of large segments of the American populace during WW II to Washington that resulted in the conditions leading eventually to the formation of this hot, young band from Maryland. “Hot” in the fact they musically are setting the bluegrass world on fire with their spirited performances, skillful instrumental work and complex vocal arrangements.

What truly sets them apart from most new bluegrass bands is their almost fanatical reverance and loyalty to old-style bluegrass and country music. The word “fanatic” itself describes someone possessed by “an excessive or irrational” devotion to a cause.

The Johnson Mountain Boys are not irrational about their love of old-style music, but it is true they live and breathe bluegrass music, and they regard the old- style form of playing and singing as the best of all possible musical worlds.

After a performance at Lavonia, Georgia, that a classical music critic might call “brilliantly inspired,” two of The Johnson Mountain Boys found themselves talking with one of their heroes, Curly Seckler, leader of The Nashville Grass and long-time sideman to the late Lester Flatt.

Seckler congratulated JMB banjoist Richard Underwood and fiddler Eddie Stubbs on their decision to play and sing the traditional style. He added, “There’s always room in bluegrass music for people who like that old sound.”

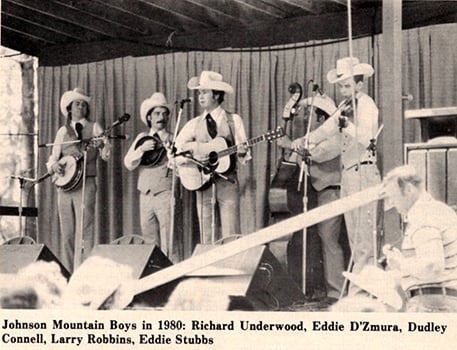

Underwood responded, “I don’t know how to play any other way.” Stubbs added with a firmly raised voice, “I don’t WANT to play any other way!” Over the past two years, The Johnson Mountain Boys have gained the attention and respect of festival fans, music critics and fellow performers. People just don’t talk about JMB. They rave about them. Words and terms like “electrifying experience,” “high energy,” “outstanding rhythm,” “hardcore bluegrass” and “intense sincerity” frequently are used.

Ken Fish, a writer in Jacksonville, Florida, enthusiastically proclaimed in the Florida Times-Union, “If these guys aren’t among the next bluegrass superstars, I’ll eat my hat —and I only have one.”

Richard Harrington, writing in The Washington Post, observed, “Bluegrass fans who bemoan their music’s accent on pop-oriented ‘newgrass’ have reason to rejoice with the (album) release of ‘The Johnson Mountain Boys’ (Rounder 0135). This Montgomery County quintet plays bluegrass the old-fashioned way without staying mired in the past…Though they’ve only been together since 1979, their music has the flawless timing and rhythmic punch of the older, ‘high lonesome’ sound…The Johnson Mountain Boys’ debut album stands with similar debuts from the Country Gentlemen, Seldom Scene and New South as a landmark in bluegrass recording.”

Bluegrass Unlimited reviewer John Roemer noted in discussing a 45 rpm release by JMB on Copper Creek Records, “The Johnson Mountain Boys seem to have heard every great, unknown country and bluegrass tune recorded since 1935. They’re truly experts in country music history…You can count on one hand the bands who can muster the emotional impact of these guys…This is the real thing, with the same spirit and power so many fans first heard in Monroe, The Stanleys and Flatt and Scruggs.”

Another Bluegrass Unlimited reviewer, Walt Saunders, observed in his backliner notes on JMB’s first album, “The Johnson Mountain Boys do not attempt to overwhelm the listener with dazzling displays of instrumental virtuosity at the expense of their singing. Instead, they prefer to use their instrumental abilities as a complement to —not a substitute for—the vocals.”

Legendary bluegrass promoter, musician and singer Mac Wiseman has used JMB as his back-up group at several shows, including one appearance at Madison Square Garden in New York in October. He said of JMB, “I think they’re fabulous. They’re just an excellent group. As long as young people like that have an input, we have nothing to worry about with the future of bluegrass music.”

On a Friday night in late July in north Georgia, I was listening to some parking lot picking when a new friend, Charlie Ready from Portsmouth, England, said he was heading back to the stage area to hear The Johnson Mountain Boys.

“Who are they?” I asked with complete ignorance. My British friend replied, “Didn’t you see their first performance this afternoon? They’re great.” Later, Ready was to say that if he had seen nothing else on his American visit than JMB, it still would have been worth the trip.

From the first moment, JMB came onto the stage after their introduction, I knew this was a band out of the ordinary mold of bluegrass groups. They didn’t just walk or hurry onto the stage. They RAN out! They jumped on those microphones and started hitting those instrumental licks like they didn’t have a moment to waste. They performed with such intensity and power, it was like being near a lit firecracker ready to burst or feeling the stem of a watch that has been wound too tight.

Over and over, JMB presented that audience with such blasts of enthusiasm, it was like never-ending ocean waves crashing again and again on a beach.

JMB showed that audience more than just an attempt at perfection in their vocals and instrumentation, they showed it right down to their outfits. For those two Friday shows, they wore white shirts with brown scarf ties and white straw hats with matching brown bands. For the two shows they did next day, they wore blue-grey pants, dark-blue scarf ties and hats with matching dark- blue bands.

Personally, the only times I have seen that level of showmanship, talent and enthusiasm in years of being involved in biuegrass music has been watching bluegrass music’s entertainer-supreme, Little Roy Lewis. There are many, many excellent singers and groups in bluegrass music, but there are less than a handful who truly know what performing is all about. Most just stand at the microphone and sing, and there is certainly nothing wrong with that when the bearer of the voice is someone like Mac Wiseman or Bill Harrell.

When you are finished watching a performance by JMB, however, you are left with mental images that linger long after the festival is over. There is guitarist-leader Dudley Connell singing with a tear-jerking voice like country singer Gary Stewart or George Jones and putting enough sorrow into his face to look like his favorite dog just died. There’s fiddle player Eddie Stubbs attacking his instrument like a gladiator battling a lion. Stubbs also bounces his right leg so fast and so hard, you almost think he would run right off that stage if it wasn’t for his left leg holding him down.

There’s Richard Underwood, jumping into the harmony while picking that banjo like he was being watched by Earl Scruggs himself. As he sings certain words, Underwood has a way of curling his upper lip that gives him a look of determination. The overall effect with bass player Larry Robbins and mandolinist Dave McLaughlin reminds one of the classic old photographs seen in songbooks and magazines of superprofessional, traditional groups.

The reaction on that Lavonia, Georgia, crowd of several thousand was itself nothing short of electric. They demanded two encores of JMB on Saturday afternoon, and they shouted, whistled and yelled for an almost-unheard-of four encores Saturday night. It was an astonishing reaction to a group virtually unheard of in Georgia and making their first appearance in the state on a stage that had seen the best.

When they finished one set, I turned to Gary Sikes, the leader of an Atlanta-based group called Brushfire, and said, “Pretty tough, huh?” He whistled low and replied, “You ain’t wrong!”

Ed Hurt, the master of ceremonies for the festival and himself a good musician, later said, “I have been emceeing Lavonia for 12 years, and I never have seen anything like those four encores Saturday night. Never in my life have I seen a reaction to any group like that.”

Long-time visitors to Lavonia could only recall past appearances by established artists like Doc Watson, Little Roy Lewis and the Seldom Scene generating any comparable crowd reaction.

“We were all just tickled to death about the reception at Lavonia,” recalled JMB leader Connell.

“The only previous experience we had similar to that great response was at Indian Springs, Maryland. It was after Indian Springs we decided it might be possible to do something with our band and make a living out of it. We didn’t second-guess Lavonia, because we had been hearing about it for years. When I came off the stage after the Saturday night (four encores) show, I was so completely wiped out that I was actually sick to my stomach. It felt good though; like after a long run.”

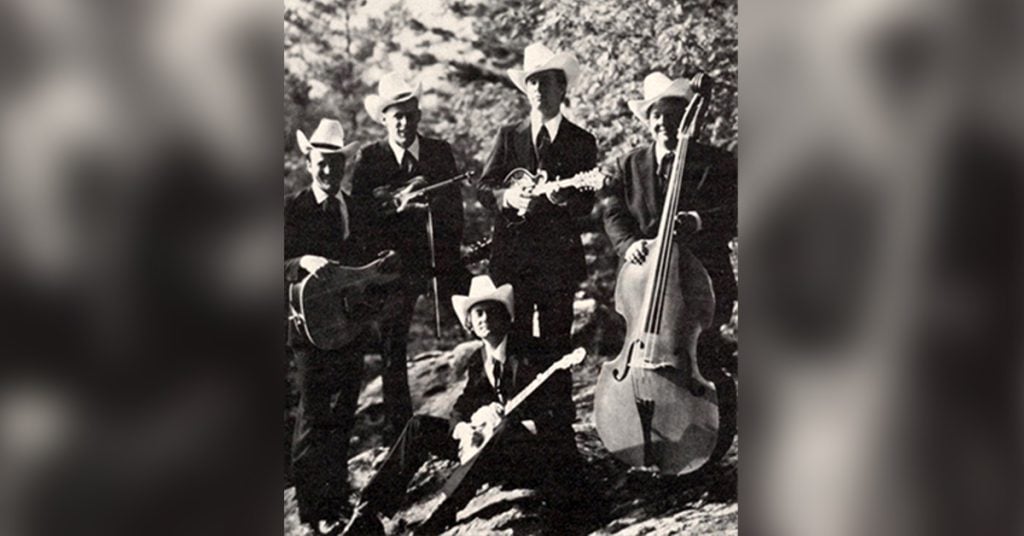

It was Connell who co-formed The Johnson Mountain Boys in 1975 as a duet with Connell on banjo and Ron Welch on guitar. One biographical sketch handed out by JMB recalls in side-show barker style of this early duet, “Their voices blended in perfect unison to produce a spine-chilling sound; a sound that told many stories of lost lovers, grief and sorrow, the hardships of life and the loss of loved ones gone to the Great Beyond.”

Now, friends and neighbors, that just about covers it all. How can you not help but like a group that sings of all those emotions and of loved ones going to the Great Beyond?

Like nearly all bands that have been in existence for some time, JMB has undergone various changes in personnel before coming to its present state. Through all those changes, Connell kept the faith.

The 25-year-old Connell plays both guitar and banjo, as previously noted. He was born in Shear, West Virginia, but found his way along with his family to Gaithersburg, Maryland. His father played banjo and his mother sang old mountain ballads.

Besides singing lead and tenor as well as playing guitar for the group, Connell composes many fine songs. Their debut album contained five of his numbers with most being in the classic, mournful style telling of broken hearts.

“When we started getting serious about our music, we started digging for material no one had done in a long time. We were also looking to create our own style of doing them. I went to a lot of festivals and concerts, and I listened to many old tapes and records. It’s a matter of always keeping your ears open, always listening for good material. Gary Henderson, a radio announcer at WAMU in Washington, had a lot of influence on my tastes due to the music he played. Before JMB became a full-time bluegrass group, Connell worked for the county’s Board of Education as a laborer, digging holes and making sidewalks.

Although he is only 19, Eddie Stubbs has brought new meaning to the term “fiddle playing.” He wrote an instrumental called “Montgomery County Breakdown” recorded on JMB’s debut album. His fiddle playing is so sharp and professional, he has been invited by Ralph Stanley to join his group on stage.

He lists among his favorite musicians that influenced him such names as Tater Tate, Sonny Miller, Del McCoury, Mac McGaha, Carl Nelson and Paul Warren. Stubbs is especially enthusiastic in discussing the late Scotty Stoneman and the late Chubby Anthony. He observed, “I only saw Chubby Anthony perform once and he was sick then, but I think his playing was the best fiddling I have ever heard at a festival.”

The teenager, who looks older and more mature due to his large physical frame, was born and raised in Gaithersburg, Maryland. His father played fiddle in local country groups on weekends and bought young Stubbs his first fiddle for $45 when Stubbs was only four.

“I played classical music on a violin in high school for three years beginning in the seventh grade. When I was in junior high and high school, I couldn’t wait to get home to put down my books and pick up my fiddle. I always have been interested in knowing who played what instruments on what sessions. Dudley and I probably have the best record collections among our band members. I spend a lot of money on records. If I like something by an artist, I want to buy everything else by them,” Stubbs related.

He first met JMB at a show date in 1978 and soon afterwards started doing fill-in work with them. Prior to that, he had played with a band called Bluegrass Image. Then, in 1979, Stubbs joined JMB on a full-time basis.

Tall, slim and 25-years-old, Richard Underwood also joined JMB in 1979. His first professional work had been with Buzz Busby and his Bayou Boys. He caught bluegrass fever in the early 1970s when he saw Earl Scruggs on public television.

“I think most bluegrass musicians start on the guitar and go to the banjo. I started on the banjo, and I didn’t want to take time away from my banjo to learn anything else. I had gone through a stage of listening to acid rock and to some jazz. I learned a great deal about performing by playing available dates with Buzz Busby. He is a real professional, and he told me things I never will forget. He said the most important thing about doing a song is to kick it off right and end it right. Everybody has an influence. I’ve heard members of our band ask the really great musicians who are their influences,” Underwood observed.

He noted of his love for old style music, “I became interested in old style music about the third week I was playing. It takes a progressive sound like the Seldom Scene to catch a young person’s ear, but I think most people gravitate to a traditional sound. Ralph Stanley once said, ‘Yeah, it seems like the old-style sound goes good everywhere.’ When I was first learning old style music, I went to a public library and I came across one of Ralph’s early albums. It had a big influence on me, but I’ve never told him that.”

Further discussing the old-style sound, he said of bluegrass music festivals, “When people go to a bluegrass festival, it’s like going to a museum and hearing the past.”

After playing available shows with Buzz Busby, the Seabrook, Maryland, native decided to attend the University of Maryland and managed to obtain a degree in business administration. He worked with Household Finance Company for a while after graduation, but he wanted to be performing bluegrass music as often as possible.

Larry Robbins is a native of Montgomery County and, at the age of 36, is the more experienced member of JMB. His parents were from Virginia and listened to country and bluegrass music in the Robbins household.

The younger Robbins gained professional experience by playing electric bass for a country-gospel music band in Howard County, Maryland. He later went to work playing with the Bluegrass Image for six years. Robbins and JMB fiddler Stubbs were together in Bluegrass Image for about a year. “I was responsible for getting Eddie into Bluegrass Image, and he was responsible for getting me in The Johnson Mountain Boys in 1979,” Robbins related.

Robbins came around to bluegrass music almost exclusively as a result of country music going more modern. He noted, “To me, country music got to where it wasn’t country. I like the sound of my upright bass because it fits the style we are playing. It would defeat the whole purpose of what we are trying to do if I played an electric bass.”

He said the trip to Lavonia, Georgia, was memorable even before the group arrived at the festival site. Robbins recalled, “We made a wrong turn and ended up asking directions at a country store. The man running the store was so helpful, and he told us, ‘I’m sure glad you made the wrong turn or you wouldn’t have gotten to see me.”

Dave McLaughlin was the only JMB member who had been to Lavonia, Georgia before their triumphant appearance at that north Georgia festival. He grew up going to bluegrass music festivals with his family as recreation.

McLaughlin is a native of Washington, D.C., and is the son of a nuclear physicist who himself plays the banjo and guitar. The 23-year-old mandolin player for JMB spent one-third of his life in the Charlotte, North Carolina, area before returning to the area of the nation’s capital.

He comes from a super musical family. Besides his banjoist-guitarist father, McLaughlin also has a mother (a real estate broker) who plays bass fiddle and piano and a brother whom he describes as “my favorite guitar player.” Most recently his brother has been performing with a bluegrass group from Arizona called “Flying South.”

Although he plays mandolin for JMB, McLaughlin remarks, “The fiddle is my main instrument. It is what I am most comfortable playing.”

Besides the guitar and mandolin, McLaughlin also has been playing th banjo since the age of five. He is the only JMB member who has been with the group twice. McLaughlin originally joined the group in January 1978. Then, he left in August 1978 to go to college. He rejoined the group in May 1981 after mandolin player Ed D’Zmura departed.

“I went to George Mason College in Virginia and majored in different things each year. Nothing seemed worthwhile. I just didn’t get into college life…My family had been going to bluegrass music festivals for years as a family outing. We went to Union Grove before it was so big, and we went to Galax, Virginia in the early 1970s before it got so big,” he related.

In discussing JMB, McLaughlin observes, “By definition, we’re traditional, but The Johnson Mountain Boys really is a progressive bluegrass band. We are progressive in that we do a lot of our own material, and we have a way of presenting old material like no one else does.”

His own favorite instrument is an F-5 Gibson mandolin that is dated May 29, 1923, “the same year that Bill Monroe’s was made.”

Although McLaughlin and other JMB members strive for individual expertise on their instruments, McLaughlin notes, “It is most important for our band to arrange our music for a band unit sound where each member is not competing with each other.

In early 1981, three members of the current JMB group were able to return to a bit of the past when they performed at the high school they had attended. Connell, Stubbs and Robbins returned to the Newman Auditorium at Gaithersburg, Maryland, High School for a special homecoming concert.

Connell later said of that appearance, “They made a big deal out of it. We had a packed house of more than 1,000 people. We had a ball.”

Perhaps, that is a good description of The Johnson Mountain Boys. They have a ball while still being performing historians of bluegrass and old style country music. They bring music through the walls of time from yesterdays.

As President John F. Kennedy so eloquently once said, “the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans.”

The Johnson Mountain Boys are now carrying that torch.