Home > Articles > The Archives > Arvil Freeman—Portrait of an Independent Fiddler

Arvil Freeman—Portrait of an Independent Fiddler

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

June 1991, Volume 25, Number 12

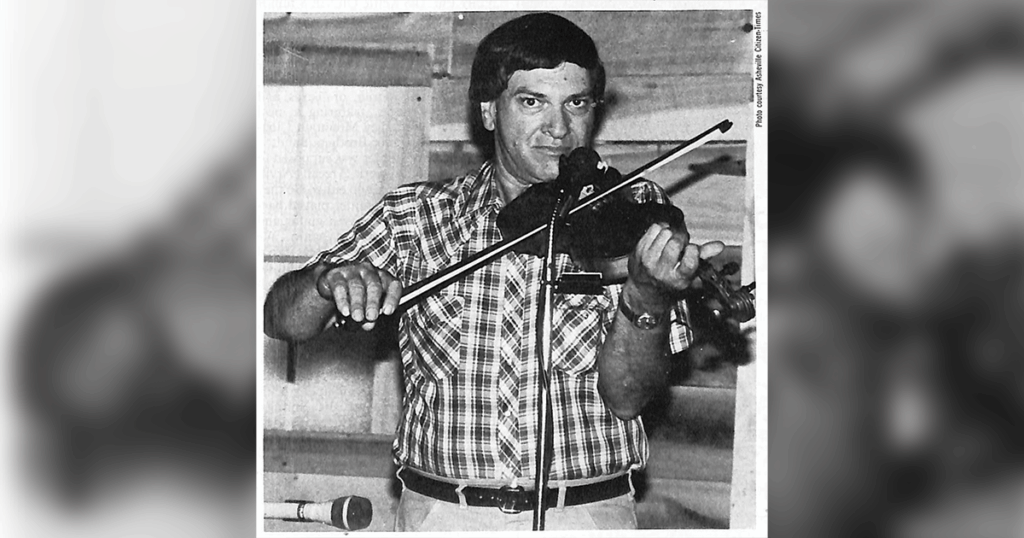

Why would any fiddle player turn down offers from Bill Monroe, Ralph Stanley, Grandpa Jones and Mac Wiseman? “I’m pretty much of an individualist,” says Arvil Freeman. “I’ve never been a person that’s wanted a lot of attention.”

In fact, anyone wanting to hear Arvil’s fiddling has to travel to Asheville, North Carolina, to do it. If you’re a fan of wonderful fiddling, it’s worth the trip. He’s equally at home playing bluegrass, country classics and western swing as well as the traditional tunes he grew up with. Arvil started figuring out fiddle licks on his older brother’s fiddle at the age most children are puzzling out their ABCs. His smooth, powerful renditions of the tunes he learned in childhood are probably the most exciting you’ll hear anywhere.

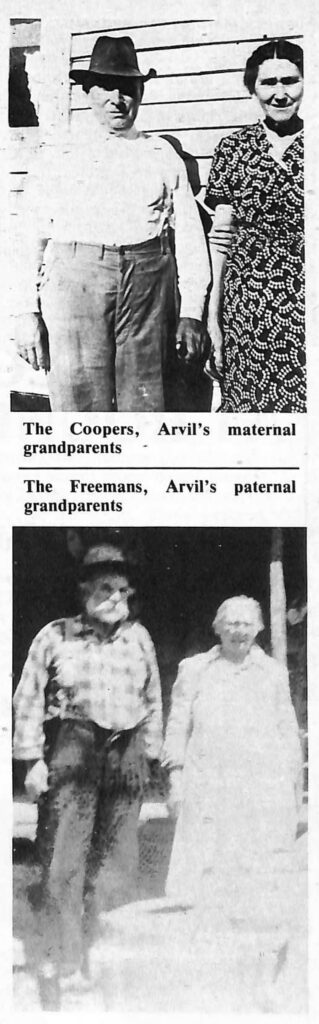

Arvil was born in Madison County, North Carolina, in 1932. His mother’s family was originally from Jenkins, Kentucky; his grandfather originally a coal miner, left Jenkins to become a cattle and horse trader. His grandmother was a full-blooded Cherokee.

“I think I go back more to my grandmother than to anyone else in the family. A lot of people recognize my Cherokee heritage just by looking at me,” Arvil says. “I’ve always loved to be outside and I love to hunt and fish. A lot of times a grandchild will take directly after a grandparent.”

Maybe that theory explains Arvil’s early love for the fiddle; his father’s father Zeb Freeman, was a fiddler— the only fiddler from a previous generation that Arvil knows of. “My father’s family was originally from Madison County,” Arvil says. “By the time I remember my Granddaddy Zeb, he didn’t play anymore. In fact, he didn’t even have a fiddle.”

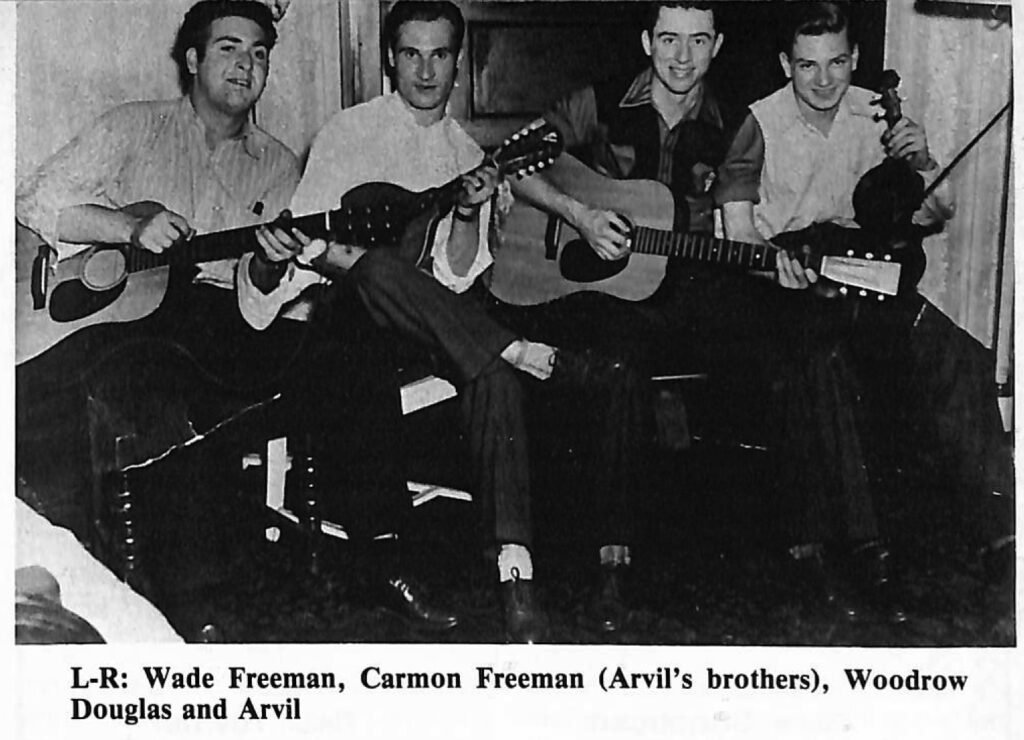

Two of Arvil’s older brothers, however, did get a Sears guitar. (“The goodest kind!” Arvil comments.) His brother Gordon then got a fiddle; his brothers playing fiddle and guitar is the first music Arvil remembers hearing as a child.

Arvil’s grandfather, Zeb, owned a large farm in the Pawpaw section of Madison County, near Marshall. Arvil grew up there, with his parents, three brothers and four sisters. “The only things we bought were flour, sugar, coffee and salt. We bought some of our clothes and shoes. My mother was a good seamstress and made a lot of our shirts, the girls’ dresses and all the quilts, of course.” Arvil remembers hearing his grandfather’s records of groups like the Skillet Lickers, the Delmore Brothers and the Carter Family. “He was reluctant to play those records, though,” Arvil recollects, he didn’t want to wear his needles out.

“I was about six or seven when I started on the fiddle. Back then, if there was an instrument around, you learned to play it, because there wasn’t anything else to do. There was no TV; people had more time. There were a lot more get-togethers and a lot more music.

“I heard Tommy Hunter (winner of the North Carolina Heritage Award in 1989) play fiddle a lot. Byard Ray another Madison County old-time fiddler was real good; I always respected his playing. I remember his old-time version of ‘Sourwood Mountain’ and he played a real strange version of ‘Polly Put The Kettle On,’ in a minor key.”

Arvil’s first professional opportunity came in the summer of 1946, when he was fourteen. Bascom Lamar Lunsford, mountain music promoter, had organized a tour of Texas and Oklahoma colleges, featuring a local clog team, the Bailey Mountain doggers and the Hunter Brothers Band.

“Tommy Hunter was supposed to go, but he had to work,” recalls Arvil. “Byard Ray couldn’t go either. So they asked me. Stanley Hunter played bass and sang, Bob Ray played guitar and Grover Robinson played banjo. We had a very entertaining show. We’d play and sing, then Bascom would do his thing—pick the banjo and sing a couple of old ballads. Then the clog team would come on. There were chaperones for the girls and we stayed in nice hotels and motels.”

The tour was into its second week when the fourteen-year-old Arvil came down suddenly with acute appendicitis in the small town of Big Springs, Texas. “There was no money involved in doing the tour,” Arvil says, “but Bascom was in the red with me, I guess, because he had to pay my hospital bills!”

After finishing high school, Arvil spent a couple of years in Michigan, where his brothers Carmon and Gordon were working. “We met Carl and J.P. Sauceman up there. They were real good singers and played guitar and mandolin. They did some bluegrass and a lot of Delmore Brothers type stuff. They were originally from Greenville, Tennessee and when we came back, me and Carmon joined their band.”

The band—the Sauceman Brothers and the Green Valley Boys, was based in Bristol, Tennessee, where they played twice a day on WCYB’s legendary Farm and Fun Time Show. WCYB’s 10,000 watts allowed the Sauceman Brothers, as well as the show’s other stars, including Flatt and Scruggs, Mac Wiseman and the Stanley Brothers, to reach a five-state audience. “We played four or five live shows a week along with the radio shows,” Arvil recalls. The band ranged through eastern Kentucky, southern Virginia and western North and South Carolina as well as Tennessee. “It was hard traveling—we had a car, not a bus. We played mostly movie theaters. They’d show the movie, then we’d come out and do a 45-minute set. We always had a full house—standing room only.”

After playing a year with the Saucemans, Arvil returned to western North Carolina expecting to be drafted; the Korean War was underway. Several months passed before he was inducted into the army; Arvil spent that time playing with Don Reno and Red Smiley in western North Carolina and in the Greenville, South Carolina area. Arvil spent two years in Korea in the army food service. He says he really got serious about his fiddling when he got back to the States. “There’s a difference between playing for a hobby and seriously playing,” Arvil points out. “When you really start getting into it seriously, it’s your heart and soul. I had to give up other things—recreational things—but I said to myself, ‘Well, if I’m going to play this thing, I’m going to try to play it good.’ I’d spend two, three, four hours a day [practicing]. I’d have a tune in my head and I’d know exactly what I wanted to do with it. Nothing ever came easy for me, though, when I was starting to learn it. It was always a pretty hard chore.”

Arvil started collecting records. He had listened to 78s of Tommy Magness’s tunes—“Polk County Breakdown,” “Dance Around Molly” and “Smokey Mountain Rag.” Now Benny Martin, Chubby Wise and Kenny Baker became favorites too. “Taken on a daily basis, I’d still rather hear Baker than any other fiddle player,” Arvil says.

Arvil spent a couple of years in the restaurant business, then worked as a meatcutter for a local supermarket chain. He continued to be serious about the fiddle, though, practicing on his own and playing with a group of musicians on Sunday afternoons. Arvil began playing professionally again in the late sixties, doing weekend shows with James and Arlene Kesterson at the Folkway Center in Hendersonville, North Carolina, and then as the fiddler for Arlene Kesterson’s New Day Country Band. This group continued, with some personnel changes, into the late seventies, when Arlene Kesterson moved to Tennessee. Arvil and the band’s banjo player, Marc Pruett, formed the Marc Pruett Band. When Bill Stanley’s Barbeque and Bluegrass opened in downtown Asheville in 1980, the Marc Pruett Band became the house band there. This talented group included Arvil on fiddle, Steve Sutton on guitar, Mike Hunter on mandolin and Randy Davis (who left his job as Bill Monroe’s bass player to be in the band) as well as Marc Pruett. The band played at Stanley’s four to six nights a week for eight and a half years. Arvil feels the band’s longevity, as well as its quality music, was due to the fact that they all liked each other. (Of course, the fact that they were all quality musicians didn’t hurt, either.) “We had all been playing together since we were young boys; we knew beforehand that we’d get along good,” Arvil says. Although the band took occasional outside work, including a week at the World’s Fair in Knoxville and a bluegrass festival in Las Vegas, they mostly played at Stanley’s. The group also recorded several albums for Skyline Records, Marc Pruett and Randy Davis’s record company, during their time together.

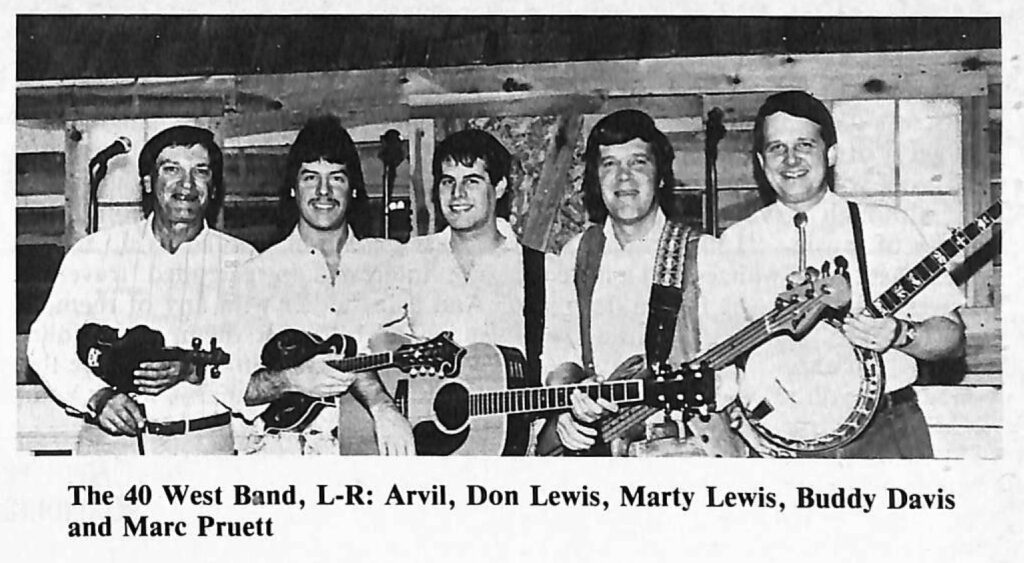

When the members of the Marc Pruett Band took leave of each other in 1988, Arvil formed the 40 West Band, the present house band at the barbeque. Current members include Don and Marty Lewis, on mandolin and guitar, Marc Pruett on banjo and Buddy Davis on bass. 40 West plays a mix of bluegrass and country classics as well as original material written by the multi-talented Marty Lewis.

Arvil’s becoming house fiddler at Stanley’s marked his transition to becoming a full-time performer; he started teaching fiddle as well. “Lots of people wanted to learn fiddle and banjo back in the late seventies,” says the musician. “It was kind of a fad back then.” Arvil began teaching at a local music store and quickly found himself with a burnout load of 23 students. Today he’s still teaching, at home, with a more moderate teaching load. He’s able to devote more time to each student this way and he’s able to pick and choose, too. “I’ve turned students down sometimes,” he admits. “I can usually tell in one lesson whether a student has any potential at all.” He feels that teaching is important for a number of reasons. “I never had anyone to show me anything much,” he explains. “I think maybe I can help someone along the way— make it easier for them than it was for me. Teaching helps my concentration, too. Concentration is essential in fiddle playing and teaching makes you have to play everything just so.”

Arvil feels the way he teaches—by memory—is the hardest, but most efficient, way to learn. “Once you learn it, you don’t forget it. You could mark your positions on the neck, but at some time you’ll have to do without it. You’re better off starting through feeling it and hearing whether you’re sharp or flat. The hard way—once you get it . . . you got it!” Arvil, like most traditional musicians, feels that fiddling can’t be written down in notes, either, because feeling can’t be written down and feeling is paramount in fiddling.

“I may use half a dozen bowing techniques in one tune,” Arvil says. “According to your arrangement, you can bow a tune with a long bow technique, or using short bows.” Anyone hearing Arvil’s fiddling will certainly be struck by the fact that he is indeed totally comfortable with—and master of—the old-time “hoedown” style of fiddling as well as more progressive bluegrass techniques such as longbow style. Arvil also points out that every fiddle is unique and requires a different approach. “There’s a certain peak in every instrument where it’s at the maximum tone. Too much pressure deadens the tone, for instance, or a real light bow, bowing every note, might not get as good a tone as using some long bow (strokes).” Every fiddler is different as well. “Two people can play the same fiddle and it’ll sound entirely different.”

Arvil owns four fiddles, all made in the 1800s, including a David Hopf. He switches fiddles often and sometimes plays the viola too. His fiddles are set up with a pretty flat bridge, which he also sands down; he feels that factory bridges are too thick and affect the tone of a fiddle adversely. Arvil’s four or five bows, like his fiddles, are all old. “I’ve seen new fiddles and new bows that were good,” he admits. “I just like older ones.” Arvil uses a wound first string, to get a fuller tone and to eliminate what he calls “that mousy, squeaky, first-string sound.” And he’s adamant about keeping his fiddles clean. “That junk about rosin on your fiddle making it sound better—it’s purely hogwash! If you keep building up stuff on the top of your fiddle, it’s like putting coats of paint on it. And rosin is so fine that when it melts, it’s like glue. The only way you can get it off the fiddle is to scrape the finish off with it.”

Although Arvil enjoys playing a variety of music—‘‘I like to play slow tunes, fast tunes, waltzes and a little bit of swing” he says—he feels a deep appreciation for the real old-time style of fiddle playing. ‘‘When you’re a youngster, you’re wanting to do the ‘now’ thing. As you get older, you realize that the older music is more important, it’s where the new music came from. People tend to forget it’s the basis of today’s music.” Arvil’s favorites among the old-time fiddlers include Manco Sneed, the Cherokee fiddler and Fiddlin’ Arthur Smith. He regrets never having met Manco Sneed, although he did get to meet and play with J. Laurel Johnson, Sneed’s son- in-law. Arvil hopes to be able to record all the traditional tunes he’s learned. “A lot of good tunes tend to get left by the wayside. There’s a bunch of tunes that everybody knows, too, but my arrangements are a little different and somebody down the line might enjoy listening to them and learning from them.”

“I’ve always had the utmost respect for Bill Monroe’s music,” Arvil says. “I’ve always enjoyed Mac Wiseman and Grandpa’s singing and banjo playing.” Arvil wasn’t tempted to go on the road, though, when asked by these performers to join their bands. “I never wanted to do it. I’m not interested in extended traveling. And as a fiddler with any of them, as much as I respect them, my fiddling would have been limited. I figure that I’ve spent all these many, many hours practicing and learning to play the fiddle… and I’m not going to let someone else dictate how to play it to me. I’m interested in keeping my freedom—the freedom to play what I want, how I want to play it.”

So—unless you get your hands on one of Arvil’s recordings you’ll have to come to him to hear him play. He’s staying put, making some of the best music you’ll ever hear.