Home > Articles > The Archives > Andrea Zonn

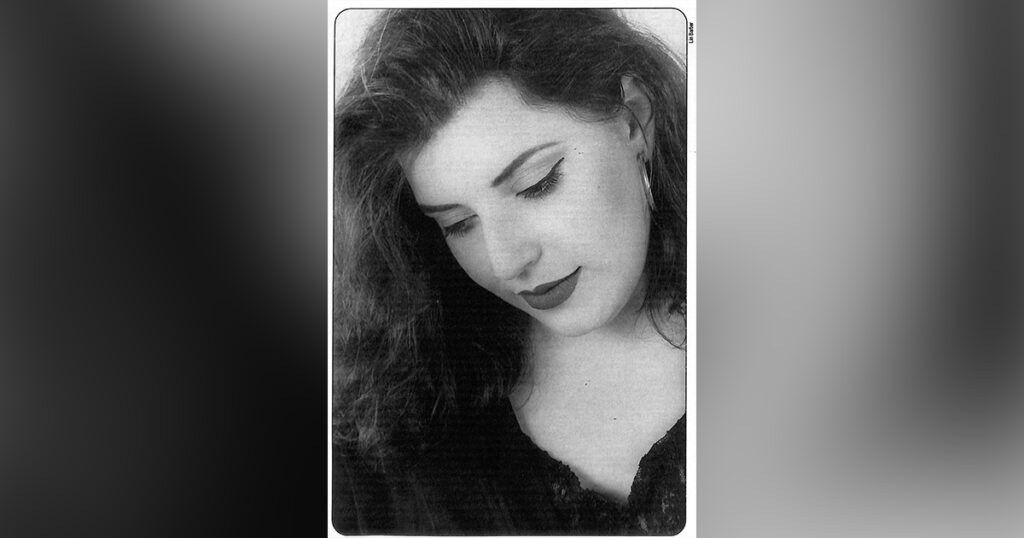

Andrea Zonn

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

December 1994, Volume 29, Number 6

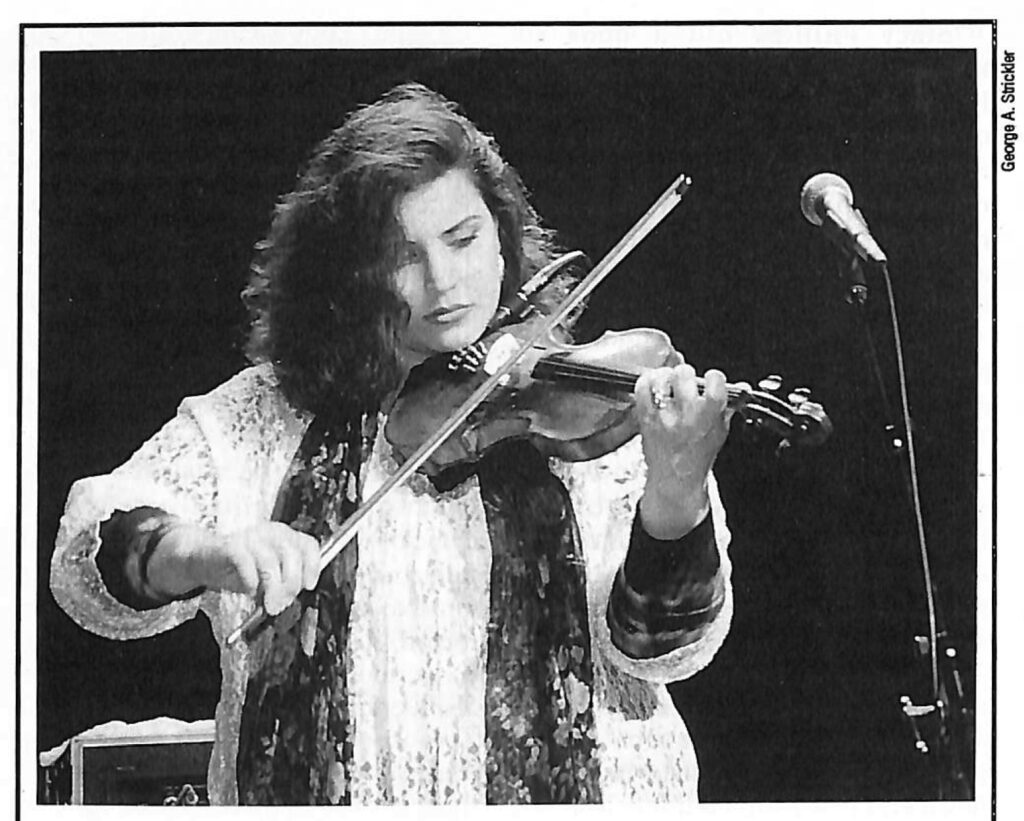

Andrea Zonn is one of the most gifted singers and one of the most accomplished fiddle players working today. She made her mark in bluegrass as a member of the Tony Trischka/ David Grier band, which evolved into the Big Dogs, and then shot through the ranks of country music to spend several years backing up another bluegrasser-gone-country, Vince Gill. Andrea was working for Gill at the time she was interviewed for this article, but is now touring with Pam Tillis.

Andrea was born into an “extremely musical” family in Grinnell, Ia., in 1969. Her parents, both classically-trained musicians, moved to Champaign- Urbana, Ill., when she was about a year old. Both Andrea and her younger brother, Brian (now bassist in the Nashville-based country band Six Shooter), were encouraged in music from their youth. “My dad is an avant-garde composer. He plays clarinet and saxophone, and is currently head of the theory and composition department at the University of Illinois. My mother is a classical oboist, and she used to give piano lessons at our house after school,” Andrea recalled. “I grew up playing classical violin; Brian grew up playing classical cello.”

Fortunately, classical training did not bind the Zonn family to only one style of music. Andrea said, “My dad has always been musically bilingual, and plays classical music and jazz, as well as the avant- garde stuff he writes. And he always encouraged that approach in my brother and me as well; to be able to speak more than one musical language. He’s got an interesting perspective in that regard.

“I’ve always kind of been in limbo between bluegrass and country, and classical music. They’ve both been of vital importance to my development as a musician. I think that both of them have helped create a certain style, or a certain personality to my playing. And I don’t think I would approach either genre of music [the same way] if I didn’t have the knowledge of the other.

“A lot of classical scholars don’t understand bluegrass. They’ve never analyzed it, they’ve never listened to it, and never given it enough of a chance to realize that bluegrass presents a whole new set of challenges that classical music never addresses—all the way from learning the music by ear, to mastering subtle inflections, to improvising. It’s just different.”

Andrea had musical inclinations from a very early age. “I started asking for a violin when I was two,” she said. “My mom and dad used to take me to symphony concerts. And out of all of those instruments, the only thing that I cared about was the violin. I just remember being absolutely mesmerized! It was one of those things where I just knew I could play it before I got my hands on it. Of course, at my first lesson, I sucked! I couldn’t do anything! So I handed the violin back to my dad, and said, ‘Thanks anyway, but I guess I’ll probably never be any good at this.’ And he said, ‘Oh no! I’ve rented this thing for a whole month. You’re going to go back and try it again!’ ”

Andrea’s violin training began with a variation of the Suzuki method. “There was a wonderful Hungarian violin teacher at the University of Illinois whose name was Paul Roland,” she said. “The Suzuki program is a very stiff technique at first for the kids, and they don’t start learning to read music until three or four years into it. Paul Roland had us reading music immediately (although my mother had already been teaching me), and taught more relaxed hand positions. He really taught us the ‘Zen of violin playing.’ In other words, letting the instrument do a lot of the work for you.

Fortunately for bluegrass lovers, Andrea took a detour on the road to Carnegie Hall. “My interest in classical dropped severely when I was ten, because growing up with classically intelligent people [like] my parents; they used to play all this wonderful music on the radio. These great concertos—Sibelius, and Tchaikovsky. And I was playing ‘Go Tell Aunt Rhody’!” She recalled with a laugh.

“I knew that I wasn’t any good yet. I could play in tune, and I could play the stuff that I was able to play well, but I wasn’t advanced enough to play these huge, technical feats. So I told my dad I wanted to quit the violin. And he said, ‘Well, now hang on. Why don’t you like it?’ I said, ‘Well, I hate classical music. I hate all of it!’

“I was just frustrated and I didn’t know how to express that. So he said, ‘Well, what if we find some kind of music that’s more fun to play, and not as goofy as these other pieces?’ And I said, ‘Yeah, if you can find that, you show me!’ ”

Mr. Zonn talked to a local fiddle repairman named Wayne Logue, who gave him a book of old-time fiddle tunes. Coincidentally, there was a fiddle contest at the upcoming Champaign County Fair. Andrea recalled, “He said, ‘Look! All you gotta do is learn three tunes.’ And I said. Three times? OK!’ So I learned three tunes on the fiddle, and my dad learned to back me up playing the mandolin. He just decided he would teach himself to play the mandolin.”

When the day of the contest arrived, a local Suzuki cello teacher had entered “all these little, itty, bitty fiddle players” in the novice competition, so Andrea convinced her father to let her jump into the next age group category. Even against the older players in her very first fiddle contest, she won second place.

“I got that big check for seventy-five dollars!” she laughed. “When you’re ten years old, that’s a lot of money! And I thought, ‘You mean, I played three songs, and I get seventy five dollars? Ok, this is cool!’ ”

The contest was also the first fiddle contest for Alison Krauss! Andrea and Alison lived just a few miles from each other in Champaign-Urbana. Although they would later become the best of friends, they did not actually meet at that time. “I laid eyes on her, but I didn’t meet her there,” Andrea stated.

Another fiddle player in the contest made a big impression on Andrea by sitting down and showing her some other fiddle tunes. “I was just amazed that he’d sit there and show them to me. And he’d keep playing them over and over again until I got them,” she said. That patient fiddler also suggested some other players whose music would interest Andrea. Her father wrote down the names, and with the help of Wayne Logue, Andrea became aware of Paul Warren and Kenny Baker.

“Paul Warren was the first fiddle playing I ever heard,” she said. “When I did this contest, I’d never heard the stuff. I was just reading the music; just memorized it. When I finally got to hear the real stuff—Paul Warren and Kenny Baker and Bobby Hicks and all of those guys—I mean, wow! And then when I finally got to go see Kenny Baker, that was it! I knew that I would never want to stop playing that kind of music.

“The first record we heard was a Lester Flatt record. I realized that there was so much singing, and the emphasis wasn’t on the fiddle. That’s what, I think, drew me to it. I’ve always been a much greater fan of the vocal stuff than the purely instrumental. I just like to relate to words, and there’s something so cool about playing behind a singer, as opposed to always being the center of attention. Just to figure out how you can compliment the singer. It’s a neat challenge.”

Andrea never took fiddle lessons. By the time she was 11, she was accomplished enough to begin figuring out bluegrass and country fiddle by ear. “I listened to some records and started getting into Byron Berline and stuff like that,” she said. “I started listening to country radio at that point, too. I was just absorbing all the fiddle that I could.” The first live bluegrass show Andrea attended, in 1981 or 1982, was a performance by Joe Val and the New England Bluegrass Boys, one of her father’s favorite bands. There they met banjoist Karl Lauber, who mentioned that the group would be playing at Bean Blossom (only a few hours away) that weekend. “That was the first time I saw Kenny Baker play,” she recalled fondly. “I just melted. Melted!”

As Andrea absorbed the nuances of bluegrass fiddling, she and her father met other musicians who played old-time style and taught her new tunes. Soon Andrea’s father began encouraging her to improvise. “That was really scary,” she said. “I remember asking, ‘How do you improvise?’ And he started drawing out all these charts, and the chord structures! He said, ‘Your one chord’s got these notes in it, and your four chord’s got these, and your five chord’s…’ And I’m going, ‘What is one, four, and five? Show me how you know what notes to play!’ ” He said, ‘Well, just start messin’ with it.’

“He’d say, ‘Go on! Don’t just play the melody! Play somethin’ else! I’ll just play these chords. You play whatever you want to over these chords.’ And I was so embarrassed!”

Soon Andrea and her father formed the Heartland Band (the name had to be changed when they discovered that it was already in use). “There was a big jazz program at the University of Illinois, so [my dad] recruited some guitar players, and he started teaching them to play bluegrass,” she said.

“Coming from such an analytical background, it was funny to watch him say, ‘No, you gotta hit the bass string and then the chord. And don’t play these chords up the neck! Work those open chords.’ I remember (the guitar students) saying, ‘I’m sorry, but this bluegrass stuff is hard! It’s hard to play something interesting on one chord for four bars.’ Sometimes the simple things are more complex.”

The Heartland Band played at square dances and all of the few available venues they could find. One of the places Andrea remembers well is Nature’s Table, a health food restaurant/jazz club at which they played for the door. Concerning square dances, Andrea stated, “I’ll tell you, if you don’t know any fiddle tunes, that’ll force you to learn ‘em! Play ‘Sally Goodin’ ’ for twenty minutes! It was a big kick in the pants, to learn to improvise.”

Andrea played with the Heartland Band until she was approximately 14 years old. “We made this…cassette that was called ‘Sweet Thirteen,’ she said. “I just wanted to do a record. So, we figured out all these fiddle tunes to do, and my dad wrote some jazz tunes and stuff, and I tried to play them. We just printed up these cassettes. My dad dubbed them at the house, and he Xeroxed the labels and everything.

“When I was about 14 or so, we put together a different band,” Andrea said. “The guys from the first band had graduated and gone on to different colleges, so we put together a band called Fourth Stream, which was like one step further than Third Stream. [There was] a name, “Third Stream Music,’ which was the combination of jazz and classical music. My dad, being as eclectic as he is, knew about it. And then he said, ‘Well, let’s take it one step further. We’ll have this element and bluegrass.’ And so, we started doing some really cool stuff.”

The combination of jazz, classical and bluegrass music, as Fourth Stream was described, is reminiscent of David Grisman’s music. When Andrea was asked if she and her father were aware of Grisman at the time, she replied, “Yes. We were very inspired by Grisman’s stuff, and wanted to experiment in that direction.

“Grisman used to come to Champaign every year and play. And I used to think it was so cool, ‘cause they’d go on these big, long, improvisational tangents, and you just never knew where it was going to go. The same goes for the New Grass Revival.

“The one thing that was really, really cool about the progressive [bluegrass, like] Tony Trischka and Skyline…was because in (traditional) bluegrass …there are so few songs that women can sing without changing the words around. And all of a sudden, here’s this whole other thing. Here’s a chick singer, Dede Wyland, singing the coolest stuff! Songs actually written for a woman to sing.

“ I think I was 14 when I met Trischka (at a local performance). Then, a few weeks later, we went and drove out to Winfield, Kans. Tony was out there, New Grass was out there, Mark O’Connor was there, Berline, Crary and Hickman. I think that was the first big festival we’d ever been to. There was such an intense concentration of the newer stuff. I loved it! I loved it just ‘cause it opened so many different possibilities. We were talking about the three chords before. I never knew there were so many more!”

During her “contest years,” Andrea finally got to know Alison Krauss. “We were kind of friendly rivals for a couple of years,” she said. “We were showing up at all the same local fiddle contests, and a lot of times in the same age category. We’d both been playing about the same amount of time. “We didn’t live too far from each other. Just across town. Then we started hanging out. We had cooperative parents who would drive us back and forth. We’d talk about music, and we worked out a bunch of twin fiddle stuff. And we still work up twin fiddle stuff when we can. She is absolutely my favorite fiddler to twin with. I guess growing up with so many of the same influences, our styles meld together in a really nice way.” Andrea enrolled in the early admissions program at the University of Illinois at the age of 15, without graduating from high school. “I’d been playing in the University of Illinois Symphony since I was 11 and I was familiar with everything about college except being in the classes, so it wasn’t that big of an adjustment for me,” she stated. However, she didn’t last long.

“I was really frustrated at the time, because my violin teacher at the University—I (had been) studying with her for about six years, and she didn’t like the fact that I played bluegrass. She thought I devoted more time to bluegrass since it was so much fun for me, and that I didn’t spend enough time practicing my classical stuff. Which was true. I never practiced anything. It was more fun for me to just jam, or I’d take out my fiddle and practice for an hour before my lesson.” Andrea’s unorthodox practicing method demonstrates the power of creative visualization. “I would mentally think about (the assignment), and just visualize what it was like to play,” she recalled. “Really try to feel what it was like, and think about what it felt like to play. So that was, I think, almost as beneficial as practicing. And didn’t sound as bad! It’s kind of a Zen thing. People think I’m nuts, probably, for saying that. I mean, certain people that have practiced for eight hours a day, twelve hours a day. There was nothing less appealing to me than that!

“So my violin teacher was saying, ‘You’ve got to make a decision. You’ve got to make a choice whether you’re going to spend your life playing bluegrass or playing classical, but there’s no room to do both.’

“I used to see these posters hanging around the music building, advertising Opryland auditions. And I said, ‘Well, I’m just gonna audition for Opryland.’ The first time I auditioned for it was actually with Alison. We went and auditioned together. I was 15. And they said, ‘Well, you’re kind of young.’ And then the next year I went back, reauditioned and got the job. I was in Music, Music, Music!”

The gig at Opryland gave Andrea the chance to move to Nashville. “Whenever I really believe in something, I go on my gut feeling, and I jump in with both feet. Always. And I did just that,” she stated firmly.

The decision to leave home at such a young age would be adamantly opposed by many parents, but Andrea is very appreciative of the help she received from her family. “My mother, even though she would have liked to have seen me go to Julliard and do the whole classical music thing, she’s always been really supportive of my desire to play bluegrass and country, and to experiment in that genre,” she said.

“My parents couldn’t pick up and leave so suddenly from Champaign, so my dad would come and stay on weekends. And I’d stay here three, four days a week by myself. They had both been intrigued with Nashville, and then they both wanted to move here. My mom came down the next summer and stayed for good. She and my brother. It worked out so well to come down here, for everybody. My brother got involved in music; and my mom certainly has a lot more opportunities here, playing in the symphony, and she does some sub work and…teaches at Vanderbilt during the summer. She’s taught at the Governor’s School for a couple of years. And some session work. She plays a lot of gigs around town.

“(Opryland) was a neat gig, because it was right out of the chute. It was a great opportunity to come to Nashville, to have the steady paycheck every week. And (Nashville) was just such a neat place! I had only originally planned to come stay for the summer and check it out, because I could have had my degree by the time I was eighteen. I thought, ‘Well, I’ll just come for this summer and check it out…and see if that’s where I want to go when I graduate.’

“Well, I loved it. I met the violin teacher at Blair School of Music, and played for him. He said, ‘We’re starting our degree program here this fall. Do you want to come and be a student? We’ll give you a full scholarship.’ And I said, ‘Well, now you’re talkin’!’ So I decided to stay here and go to school.”

Andrea continued studying classical violin until 1990, and she seriously considered entering the demanding world of professional classical music. “Who knows? In twenty years, or ten years, or five years, I might decide to focus more on that again,” she declared.

Andrea attended Vanderbilt University’s Blair School of Music while working summers at Opryland. Then a new opportunity was presented. One summer she was awarded a fellowship to the prestigious Aspen Music Festival, and came home from the intensive academic atmosphere feeling “just burned out.” Soon after her return from Colorado, Tony Trischka and Skyline performed in Nashville, and Trischka invited her to a jam session at David Grier’s house. On the way back, Trischka invited her to join a new band he and Grier were forming.

“I thought, ‘Wow! Tony Trischka’s asking me to be in a bluegrass band! That’s too cool!’” she recalled. “And it would involve a lot of singing. Most of the singing I’d been doing up to that point was…harmonies. I love singing harmony parts, but I hadn’t really found my own solo voice yet. So that was kind of a neat opportunity to sing some lead vocals. On-the-job training!”

Since the band needed a bass player, and neither Trischka nor Grier are singers, Debbie Nims, from the band Clear Fork, got the job and moved to Nashville. The newly-formed group spent eighteen hours in two days rehearsing for their first gig at the Station Inn. Andrea said, “It was just jam-packed! I was so nervous, because I saw Jerry Douglas and Bela Fleck and…Oh, man! And Debbie and I were just exhausted, and our voices were so tired. But we got through it. It was fun!”

The group needed a mandolin player (and the women demanded another singer), so Harley Allen was recruited about three or four months later, in the spring of 1989. The Big Dogs toured extensively, performed an important showcase at the IBMA Trade Show in 1990, and released a well-received CD recorded live at the Birchmere in Alexandria, Va. Unfortunately, the band only lasted about two and a half years.

The breakup of the Big Dogs was a painful but educational experience for Andrea. “Tony Trischka said, ‘Andrea, if you want my advice, don’t sing bluegrass. I’m not making much more money than I was in the mid-’70s. Maybe even slightly less.’ ” “And then I thought, ‘Well, I’ll get a country gig.’ ”

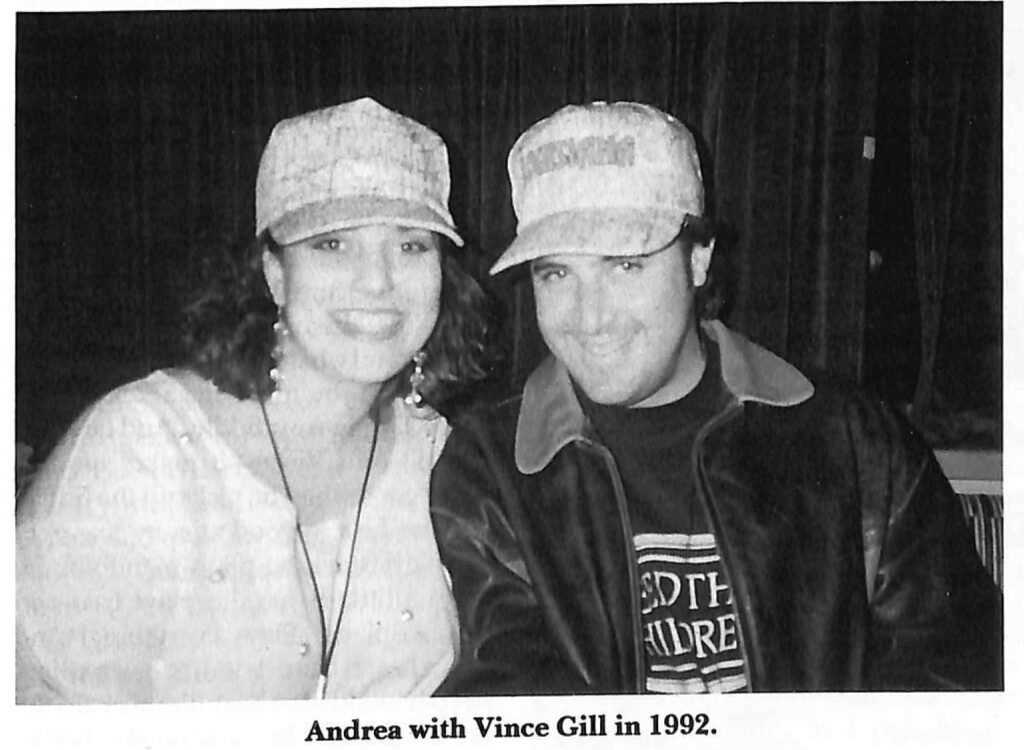

With amazing good fortune, the “country gig” Andrea got took her right to the top of the charts. “This is really weird, but the only person I really could think of that I wanted to work with was Vince Gill, because he came from the bluegrass background,” she said. “I knew that he was a great player, a great singer, and a great writer. Of course, my perception of country music was really naive at that time, too. I thought that it was playing to 20,000 screaming people all the time, and it wasn’t.”

Harley Allen knew Vince Gill from Gill’s bluegrass days, and managed to get backstage at one of Gill’s Nashville performances to give him Andrea’s tape. She called Gill the next day, and asked if he was interested in hiring a female singer. He called her back and they talked about her playing experience. According to Andrea, he was concerned about taking a woman as young as she was at the time (20 years old) out on the road with an all-male band and crew. “It’s strange to have a woman out on the road in a crew of all guys, especially as young and naive as I was,” she said. “It was like a fatherly concern.”

Andrea continues the story.“ He came out to see me play, and then we talked about it for about a month until he…finally called and said, ‘Let’s just go on the road.’ I’d been working with Mark O’Connor on some transcriptions, and I called my mother to tell her I’d be late. She said, ‘Vince Gill called! You’d better call him!’ So I called Vince, and he said, ‘Hey, you want to go out on the road?’ And I’m standing in Mark O’Connor’s basement, jumping up and down, going, ‘Oh, man! Oh, cool!’

“It was terrific. I went out for a three-day weekend. He said, ‘If I like you at the end of it, I’ll hire you.’ So after three days, I hadn’t really spoken to him much. And I said, ‘Just so I know, did I get the job?’ He laughed. He said, ‘Yes!’

“It’s been really wonderful. He’s a great boss. Because not only is the music great, and he sings and plays and writes so well, but he knows what it’s like to be a sideman. And so he gives us the opportunities to stretch out and play and to be ourselves.

“He also got me into recording. He had faith in me, and I was so intimidated! We went in to do the ‘Pocketful Of Gold’ album, and I did all the fiddle stuff first. And there was one tune on there that I just…couldn’t…get. Just couldn’t play it. I couldn’t do what they wanted.

“I was in there for 45 minutes! And my self-confidence just kept getting smaller and smaller and smaller, and I started crying. I didn’t want them to know it. And they’re going. ‘OK, we’ll run it one more time. Now, we need happy, goodtime playing.’ I was trying to play ‘bluegrass cool’ licks.

“‘That’s not what we’re looking for.’ I was just playing the same thing over and over and over. And I started crying.. And Vince says, ‘Are you OK?’ And I went (softly, tearfully), ‘Mm hmm.’ And he says, ‘Hang on a minute, Tony.’ So he turns off all the machines, and he comes in, and he says, ‘What’s the matter, Bud?’ And I said (loud, crying voice), ‘I know you wish you’d called Mark O’Connor!’

“He said, ‘What are you talkin’ about?’ I said (loud crying voice), ‘He would have been in here so fast, and he would have played it twice and got it just right, and I’m takin’ forever, and I’m sorry!’ (Laughter) He said, ‘That’s not how it works. Everybody takes a long time. You just do it. You just relax, and it just gets a little better.’ We had a good heart-to-heart for about 20 minutes.

“And the funniest thing was, during that little discussion, I said, ‘I don’t understand what you really want. I don’t know what you’re talking about.’ Vince says, ‘Gimme your fiddle.’ And he starts playin’! And Vince—it makes me feel really good when he picks up the fiddle, because he’s so good at everything else! He plays steel, he plays mandolin, he plays a little banjo, he plays bass and drums, piano. Plays everything! And he’s always been good at everything. And then I love to hear him pick up the fiddle, because he sucks on the fiddle! (Laughter).

“So he played it, and he said. This is the idea.’ And then, it was the most amazing thing. The pressure had been lifted, and then in the first take after that, I got it!”

Andrea’s casual mention of doing transcription work in Mark O’Connor’s basement was a project I was unaware of. Andrea was asked to elaborate, and replied, “I met him at the Winfield Festival, and we just spent a lot of time talking. He was really sweet.

“But anyway, when I got to town, he was one of these people that really intimidated me. I was just terrified of him, and didn’t realize how down-to- earth and nice he was. And then the Country Music Foundation put out ‘Mark O’Connor: The Contest Years.’

“Stacy Phillips did a book of transcriptions to go along with the album. He’d sent this big stack of transcriptions over to Mark’s house, and Mark is not really fluent at reading music. So he called me up and said, ‘Hey, would you come over here and read these down, and I can tell you if they’re right, and do the corrections?’ I said, ‘Sure.’

“So we would listen to a fiddle tune and I’d look at it as it was going down, and then I’d start playing through it. He’d say, ‘No, this inflection isn’t quite right. This is what I’m doing’. How would you write that out?’ And so I’d have to figure it out myself, and then transcribe it. It was neat, because it was the first time, really, that the classical (training) and the fiddle were going hand-in-hand. And it was a unique opportunity for me, too, because it got me inside of his playing a lot more than I ever would have (otherwise). I was never the type that sat down and really copied fiddle licks. I’d never sit down and tear apart these fiddle tunes that I’d listened to, and learn them note-for-note. I just didn’t do that. Working with Mark was like a Master Class.”

Another wonderful experience Andrea gained through working with Vince Gill was the chance to record with country music icon George Jones. Vince Gill’s band was on tour, performing between George Jones and Conway Twitty. (“And that’s awesome enough as it is!” Andrea said enthusiastically.) Andrea was familiar with Jones’ music because Mike Bub (Del McCoury’s bassist) and (Osborne Brothers guitarist) Terry Eldredge had played for her a CD called “George Jones: Don’t Stop The Music.” That CD contains classics from the 1950s through the 1960s.

Andrea said, “There were two songs on there that just knocked me out! One was called ‘The Likes Of You,’ and the other one was called ‘Mr. Fool.’ So I asked George, ‘Do you remember these songs? Do you ever do these songs anymore?’ He said, ‘I don’t believe I remember how they go; I’ve done so many. Why don’t you sing ’em to me?’ “So I sang… what I knew of the song, and he (said), ‘Hey, I like that song! I recorded that?’ And I (said), ‘Yes, you recorded that! In the ‘50s!’ And the next night, he said, ‘Sing that song for me. I’m fixin’ to go in and record. I’d like to redo that song. How’s the rest of it go?’

“I didn’t know all the words, so I sang what I knew, and he started singing with me. And the third night, his wife was standing there, and he said, ‘Nancy, come over here and listen. Sing that song for Nancy!’ And so we’re singing together! Me and George are standing backstage singing together! And I’m just going, ‘Oh, I can’t stand this! This is too cool!’

“And then I said, ‘Well, I’ll let you get ready for your show.’ I walked off about twenty feet. And then Nancy came up. George is apparently really shy, and believe it or not, he is one of the most humble people. He (has the) most gentle demeanor you’ll ever run across. And his wife comes up to me and says ‘George wants to know if you’ll come sing on his record.’ And I started crying. I said, ‘Are you serious?’And she said, ‘George, look! She’s cryin’!” (Laughter).

Another country star with whom Andrea recorded is Randy Travis. “I think it was a compilation of a bunch of different artists that were putting together songs for the Special Olympics,” she said. Mark O’Connor was on tour with Marty Stuart and Travis Tritt, opening for them, so he was out of town, and they needed to get it done. So Kyle (Lehning, Executive Vice President and General Manager of Asylum Records) called and said, ‘Can you come in tomorrow morning and do this thing? Mark recommended you very highly.’ And I said, ‘Well, sure!’

“And so I went in there and did this song, and then the next thing I knew, Kyle was calling for more Randy Travis stuff. Randy’s album, and Dan Seals. Kyle started using me for some different things.”

Does Andrea consider herself a “major player” in the world of country and bluegrass now? She replied, “Well, I don’t like to say ‘yes,’ because it sounds so conceited. But I can see the tables turning. When I was a kid, and going to see people like New Grass Revival and Kenny Baker—just the feeling that I got looking up on the stage and going, ‘Man, I want to be doing that!’ And then to be doing it, and especially in such a big situation!

“I’ve started to see people that do recognize me. There was a little girl that came up to one of [the Vince Gill] concerts at Opryland. She had on her T-shirt with a fiddle on it, and it said, ‘Andrea Zonn.’ And she was this huge fan. I just couldn’t believe it! And I thought, ‘I was her one time!’ I just hope that I can contribute something.”

The long miles, bad food, late hours, and strenuous work of a country vocalist can be damaging to the best of voices. Andrea sings with great poise and precision. In order to protect her voice, she took some lessons from another classically-trained bluegrass musician, Kathy Chiavola. “I took about four or five lessons a couple of summers ago,” she said. “I’d been singing for a long time, but I wanted to make sure I wasn’t doing anything wrong, breathing-wise, or anything harsh on my throat. I’d seen a lot of people that were having trouble with nodes, and singing improperly. And I wanted to learn some warm-up exercises. Stuff that I still don’t ever do!”

When asked to characterize her performing style, Andrea replied, “That’s a tough question. I never wanted to be a clone of anybody. I try to voice myself through my playing and through my singing. I try to play with integrity, and I try to play with a certain amount of musical intelligence, rather than just floating through the changes. I try to play stuff with direction, and when I do improvise or do a solo, I like to think that it’s not going to sound like I’m just bumbling around.

“As far as specifics, I guess, coming from a classical background, my intonation is probably one thing that people would notice. Fiddle is definitely an instrument you can notice if it’s not in tune! So I try to pay special attention to things like playing in tune and getting a really good tone. I like to play with a lot of clarity and try to be as smooth as I can.”

Concluding Additional Note From Andrea:

As Dan mentioned at the beginning of this article, the interview was done while I was still touring with Vince Gill. Perhaps the most-asked question I get is, “Why in the world did you ever quit working with Vince?” I actually left to finish my degree, which I finally completed after nine long years. I now hold a Bachelor Degree of Music, with emphasis on Violin Performance, from Vanderbilt University. My mother is so proud!

After graduating, I was offered (and accepted) a gig with Ronnie Milsap. Ronnie has always been one of my vocal heroes, and like Vince, his live performances are no disappointment. What many people don’t know about Ronnie is that bluegrass was a big musical influence for him, along with many other genres. It was interesting to perform music that was part-oriented, rather than improvisational, with vocal arrangements that involved big, blocked harmonies, instead of spare, bluegrass-styled voicings. I learned a great deal from the experience, but after many months of persuasion, I left Ronnie’s band to go with Pam Tillis. I felt this move would present greater musical challenges.

I started with Pam in January of 1994, and have enjoyed singing with another female for the first time since the Big Dogs. I’ve also had the opportunity to fine-tune my guitar chops. Pam is an unbelievable vocalist and very knowledgeable about her craft. It’s a real pleasure to work for her! (Plus, I can borrow her makeup, which I couldn’t do when I worked for male artists!)

I’ve also been trying to rack up my recording credits, working on such projects as the Cox Family’s records (with Alison Krauss in the producer’s chair) and Larry Perkins’ all-star album . Other work has included George Strait, Steve Warmer, Tracy Byrd, Nanci Griffith, and Bobby Cryner. I’ve kept my hand in bluegrass by singing on Terry Eldredge’s new album.

Finally, I’ve been working on putting a new band of my own together called the Twilight Zonn. It’s an electric band that combines the elements of country, rock and roll a la Dixie Dregs, R&B, folk and, you guessed it, bluegrass. Quite a handful, but with any luck, it will help me define the sound that’s been in my head for so long, and in so doing, will make it oh- so-much easier to pursue the ever-popular record deal.

It’s been busy, but that’s how I like it!

[Editor’s Note: The commercial country business being what it is, side players can change bands frequently and Andrea’s already got yet another new boss. She ‘s just been hired by Lyle Lovett!]