Home > Articles > The Archives > An Interview With Bill Clifton

An Interview With Bill Clifton

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

March 1968, Volume 2, Number 9

April 1968, Volume 2, Number 10

May 1968, Volume 2, Number 11

R.K.S.: This is August 9, 1967 – This is Dick Spottswood, I’m sitting here in my Takoma Park apartment. With me is Andrew Townend from England, Gail Swinburne my neighbor from Takoma Park and Bill Clifton who has graciously allowed me to interview him for a few minutes for Bluegrass Unlimited. And I’d like to start with a few vital statistics. Where were you born?

CLIFTON: Where was I born? I was born in a little place called Riderwood, Maryland. My mother says on the kitchen table, and her father was a doctor fortunately, 5th of April 1931.

R.K.S.: Did you begin playing music as a child?

CLIFTON: My first interest in music came at one of these children’s parties that I was invited to along with all of my sisters and 500 other children or thereabouts, and there was an accordian player. I think I was about 4 or 5 and I can remember this accordian player playing the popular music of the day and the newest song out was a thing called “A Tisket A Tasket, I’ve Found My Yellow Basket” or “I Lost My Yellow Basket”, I think it was, and some child asked him to play it and he hadn’t learned it yet because it was too new and so he asked the child if he would hum this tune and the child hummed the time and he played it like a wizard on the accordian. To me it was like a wizard; I’d never heard anyone play an instrument which wasn’t working from notes, and I was so impressed with it that every birthday and every Christmas from then on I asked for an accordian. I figured that the only way you could do this would be on an accordian and that’s where it happened. I finally got one, for a birthday I think, when I was twelve years old. I was overjoyed and my father said “there’s only one catch, I only rented it for 30 days. It goes back at the end of the month unless you learn to do something with it.” Well, I didn’t take any lessons, but I learned a lot of the old Stephen Foster songs as fast as I could. At the end of the month I could play maybe 8 or 10 songs and he said he would make arrangements to buy it.

Kept it for about 2 years actively and it got too heavy to tote around so I traded it for a guitar. Really, my interest was in country music anyway, and accordians didn’t seem to fit in too well.

R.K.S.: When did you first hear country music? Was it always part of your background?

CLIFTON: No, I think probably that the first time I can remember hearing it was the WWVA Jamboree in Wheeling, West Virginia. I have one sister Anne; I have four sisters, but my sister Anne (who is the next one to me in age) was a great fan of country music at an early age and every Saturday night she would turn on her radio to WWVA and listen to the Jamboree. Her room was next to mine, and I got to listening to the music and liked it. I can remember going in to make my first record purchase in the city of Baltimore, and I went into a shop that sold, you remember in the 40s they used to sell, well in fact I suppose from the beginning of records there used to be special stores that would designate RCA Victor records sold here; you couldn’t buy a Columbia record in there, it was RCA Victor records. Well, I went to one of these stores and it was during the war (it was about 1944). I must have been about 14 or so, and I bought three records, RCA Victor records, from this store, one was the Morris Brothers singing, Wiley and Zeke singing “Salty Dog Blues” and “Somebody Loves You Darling”; another was “Keep On The Sunny Side” and “When The World’s On Fire” by the Carter Family, and the third was Eddy Arnold, “Did You See My Daddy Over There”, I think it was, and “I Walk Alone”. That’s the pairing, and my tastes have always remained about that in’ that proportion. I still like to hear a lot of country music, but only about one third to two thirds old time.

R.K.S.: The songs of Eddy Arnold and people like him are doing today, are they songs that you can occasionally find pleasure in?

CLIFTON: Well, that’s stretching it a little bit, but I think that some of the modern country people like George Jones and, well let’s see, I really can’t think of too many of the names right now, I don’t know them all, but there are a few singers who come along occasionally who sing things which I think are well done. I wouldn’t buy the records but I still enjoy hearing them, but I would still buy old time records whereas, let’s put it this way, I would buy it if there were another Mac O’Dell around. There are people who show up like Mac O’Dell and Jimmy Osborne, people who sing old time songs, but in a more or less modern country way. Modern, pre 1953, pre Elvis Presley, and if they sing them in a nice way, Roy Acuff for example, I just love them.. I think they’re great; I enjoy Ernest Tubb occasionally and some of the others who have been singing these songs for a long time who would be called of the modem school rather than the old time school.

R.K.S.: Well, it’s interesting, though, that of the names that you mentioned, even though these people perform modern material, George Jones, Eddy Arnold, Ernest Tubb, all of them have very extensive backgrounds and have been recording since well the 30s for Ernest Tubb, Eddy Arnold a decade later, and even George Jones has been around for quite a while. Do you think the newer singers that are emerging have the same depth? Can they lend the same amount of interest to their songs, people like Dottie West or, well, some of the people like Dean Martin, now he’s attempting to do country material and the country stations play …

CLIFTON: Well, you’re asking the wrong person, ’cause I really haven’t heard much in the way of modern country music in the last four years, but every now and then I do hear one which I like, and when you say “do they have the depth”, and you ask about specific singers, the ones you asked about I haven’t heard. I mean I’ve heard Dean Martin; I haven’t heard him do a country song.

I’ve probably heard Dottie West; I don’t remember having heard her, but the name is certainly familiar. I wouldn’t have any real background on any of those particular artists.

R.K.S.: By the time you were a teenager you had begun to buy records regularly and to play regularly on the guitar. Were you learning songs by this time that you were singing?

CLIFTON: I started learning from radio. If I could copy the words down fast enough, write fast enough to copy down something like “Put My Little Shoes Away” or something like that, I’d copy it down just as quickly as X could get it down and learn it. I didn’t know how to play guitar at all so I got a little book with the guitar which said “This is your plectrum.” People always ask, “Why do you play with a straight pick?” The answer is, I bought a guitar book that said “this is your guitar and this is your plectrum.” I didn’t know there was another way, I thought that was it, and when I heard Maybelle Carter playing guitar I figured that’s what she did it with. It wasn’t until 20 years later that I found out that I was wrong. I used to try to imitate Maybelle’s guitar style as closely as I could, and because it was simple and to me it was very effective, but it seemed simple enough for me to learn it. That was before I realized that she had so many different styles, but the basic strum or the basic concept of Maybelle’s guitar playing is one that most people can deal with without having to go out and take lessons. You can listen to it and pick it up and that’s what I was able to do.

R.K.S.: When did you first begin to perform in public for other people?

CLIFTON: Well, I never got any encouragement from my family, in fact I got nothing but discouragement; maybe that’s the reason I still play. I told you I could do it, this kind of thing, but the situation with playing around Baltimore, Maryland in those days, well, first of all it was during the war that I started to play, and gasoline rationing was on, and the only place I could get to was Fullerton, Maryland which is out off the Bel Air road north of Baltimore and we used to have, I can’t even remember the name of the place now, but it was a big old barn building, and they used to hold barn dances and square dances in there. The people who played there were two brother named Pierce and one of the Pierces had a son who was my age. Well, going back to 1947 when Merle Travis first started to play, Billy Pierce was the only person I ever knew who had been able to work out what Travis was doing, and I think Billy still plays very nicely. I don’t know that he plays professionally even, but he has done some radio work around Baltimore and he’s a good guitar player. I used to go up there and play at the barn dances for the experience of playing and singing, and also ’cause I liked to learn the songs. I had a little old Wilcox-Gay disc recorder that I’d gotten for a Christmas present somewhere along in there, and I used to take that out there and record the band for the square dances. I must have gotten 75 verses to songs like “I’m Going Down That Road Feeling Bad” and things like that you know over a period of months, but they always make up a bunch of new ones every night. I suppose you get a little bit of the atmosphere in their music when you learn that people do this; it’s not all a set song that you only can sing one way.

R.K.S.: You mean as you might hear it on a record?

CLIFTON: Yeah.

R.K.S.: Did you do any other active playing around Baltimore?

CLIFTON: Well no, that was all I did, that was in my early teens, middle teens. I was away in school in Florida till I was 17, then I came up to the University of Virginia in Charlottesville and I started radio doing an early morning program.

R.K.S.: Did your family move to Charlottesville or did you go by yourself?

CLIFTON: No, I really went to the University and just got involved with a number of things. I put a little ad in the Cavalier daily, the local or university newspaper, in which I asked if anybody else was interested in old time music or country music I’d like to get in touch with them and meet them, because I didn’t know anybody who was at the school there. I had a lot of

different people who wrote; some of them came around and brought guitars and banjos around and played at ’em, but only one that I really found much enjoyment from, and that was a fellow named Paul Clayton. Paul and I were in the same class starting off at the university. Paul used to come down and work with me on the early morning radio program I had, and then he had his own program on a Sunday evening at the other station in town. There were two stations then, and I worked every morning. As I remember I was on from 6:00 to 7:00 every morning.

(CONTINUED FROM LAST MONTH)

CLIFTON: Also in 1950 during the summer vacation I went up to Baltimore to stay with my family and I worked at WBAL and WBMD in Baltimore. WBMD is a full time country music station and WBAL had a sort of Saturday afternoon. It was a jamboree is what it was; it lasted four hours if I remember right, three or four hours and I got two fifteen minute segments of the four hours.

Zeb Turner (is that his name?) used to play with Ernest Tubb at one time I believe, anyway he used to run this thing and Ray Davis was part of it some way or other and I spent the summer there. Then I went back to Charlottesville in the fall of 1950, and took another little radio program down in Virginia on a Saturday for a furniture company three times a day. I was on at meal time, I think. The first program was on at 8:00 in the morning until 8:15, the next 12:00 to 12:15 and the other 6:00 to 6:15 and I did the three fifteen minute programs each Saturday.

At some point not too long after that I decided I’d like to work on a radio station over in Richmond; so I went over and got an automobile and used car lot to sponsor me for half an hour on Saturday afternoons from 3:00 to 3:30. I did an interesting thing there, I mean…

R.K.S.: Were these all solo spots, you know just you and a guitar?

CLIFTON: Yes. You know I mentioned Paul Clayton a little while ago. Paul used to come up on WINA in Charlottesville with me in the morning. I used to play mandolin and he used to play guitar and we’d do duets, but that was only very rarely.

R.K.S.: Wasn’t there a story about that, isn’t that how you took the name Clifton?

CLIFTON: Well that’s not exactly how I took it. I used to teach guitar; I had no background for teaching; I should never have been allowed to teach, but there was a little place called the Don Warner Studios which was from Richmond, Virginia and had a studio in Charlottesville and they wanted somebody to teach guitar and they asked me if I would do it and I told them that I was not qualified because I had never taken lessons myself and I didn’t know how to read music and I didn’t really think I could teach it. He said, “these are all just beginners; these are people who are just starting.” The first guy I got was a truck driver who played all the time when he was on his truck. He could play circles around me, but he took eleven lessons before he realized it. While I was doing this, the Don Warner Studio, the place where I taught guitar, it was right next door to the radio station, in the same building; it was in the next room over from the radio station. The manager of this radio station used to come over from time to time and just chat with me and he asked me if I would do this morning program, and I said yes. Then I got thinking that my family has never been very interested in the music. In fact, I felt that they might really be offended by the fact that I was going to do radio work; so I decided to change my name at that point. Also, nobody could spell my name and I get tired of looking at it misspelled; so I thought I should pick one everybody could spell. I picked Clifton, and the first thing I knew I got “Clifteen” and “Cliftan” and just every kind of spelling you could think of within the first couple of weeks after I picked it. So that didn’t work out too well but I’ve just stuck with it ever since then.

R.K.S.: Well, when did you first form a band?

CLIFTON: By 1952 I was thinking in terms of doing something more than local radio around Charlottesville or Baltimore. The thing I really wanted to do was go to the Jamboree in Wheeling, West Virginia and work up there. I didn’t feel I was really good enough to do it on my own so I thought it would be nice if I could form a group. Paul Clayton used to live on the top floor of an old building right near the University and I was walking up to his apartment one day when I heard this fabulous 5-string banjo playing coming out of this apartment below Paul’s. It had nothing to do with Paul at all; it was just a student who lived in there. But the banjo player just knocked me out. Also I found out that he was singing tenor and that sounded pretty good to me, so I just walked in and introduced myself. His name was Johnny Clark, and he had come down to play banjo with a student who lived down there. I talked to Johnny about singing something and we sang a few together. We liked it and decided that we ought to work out some more together. I asked him if he knew any fiddle players, and he said he knew one, and we drug a boy from Culpeper by the scruff of the neck down to play fiddle with us. I went back to Richmond and worked for the same radio station I’d been working for, this used car lot, and …

R.K.S.: Who was the fiddle player from Culpeper?

CLIFTON: A boy named Winnie Sisk. Winnie and John and I formed this group, and we used to do a radio program every afternoon for this used car lot, or, in fact, come to think of it, I don’t think we were sponsored; we did it with the hope of ….. he didn’t take us up on it. We didn’t have a sponsor. We played on this thing every afternoon fifteen minutes, I believe it was, a short program, and then we decided things weren’t going so well. We weren’t getting a sponsor and nobody seemed to be really interested. We’d been there a couple weeks, three weeks, every day working, didn’t have any income for anything else, so we went over to another radio station, WLEE, and there was a fellow over there, a salesman who had a long standing relationship with Dr. Pepper. Dr. Pepper had been known to sponsor a country music program from time to time, so we thought, well we’ll go over to see him, see if he can get us Dr. Pepper for a sponsor, we’ll come over on his station. So we went over there and talked to this fellow and he listened to us and said, “yeah, I think we can do something,” and that was like on Thursday. Then on Saturday we were listening to WWVA and they announced that the Davis twins would not be on because Skeeter Davis’ sister had just been killed in an automobile accident. Sounds little bit morbid but anyhow we thought, that means there’s one less group at Wheeling, and maybe there’s a chance for us to go up there. So we drove up; we left that Sunday right after listening to this program and drove straight through to Wheeling and talked to them about working on the Jamboree. They said, “yeah, you can start right away on the morning program.” So we started, and then a friend of ours who we had left in Richmond phoned up and said, “well, you got your job, and you’re sponsored by Dr. Pepper at WLEE.” There we were in Wheeling, no income again. They didn’t pay us any money in Wheeling, but we thought we’d go back for the money they’d pay at WLEE. But we really wanted to stay in Wheeling, so we took a chance and we stayed there. We had a real good time; we didn’t make any money but we had a real good time. We went up on tour with Cowboy Phil and the Golden West Girls (he had different groups of girls for a long time but by the time we went with him he was down to one girl) and we took a tour up in Vermont and New Hampshire with him. We worked seven days a week. I kept all the big money; I earned $8 a night and Johnny Clark and Winnie Sisk earned $6 each. We stayed up there for two weeks and then we came back and we did the morning show for a long time. It was a good experience; we had nice mail coming in, and we enjoyed it. But we still weren’t making enough money to live off of. We kept hocking our watches and never knew what time it was.

Then we drove…..we left there one day and we went to visit A. P. Carter down in southwestern Virginia. We’d been down to see A.P. in the summertime when we’d been working at Wheeling, and A.P. had built this park which he wanted us to play in. We said we would, and he said “I wish you boys would come to work down here. There’s a radio station over here in Kingsport (Tennessee) that is just dying to have you come down.” Things weren’t too extra special up in Wheeling, so we went over to this radio station and we did a program over there, A.P. Carter and Johnny Clark and myself; just the three of us. After the program was over the manager came down and he said, “pst pst, can you come upstairs and visit with me for a minute.” So I went up, and he said, “how tied down are you at WWVA?” I said, “well not too, why?” and he said, “well, we were just thinking, we’d really like to have you come with the station here. We’ve got a couple little sister stations and we’ve got a lot of work and play a lot of shows around here; we can make some good money.” So I said, “well, all right. Can you guarantee us a weekly salary?” and he said they could guarantee us a certain weekly salary; it was $120 or $125. We said, “all right, we’ll come, and we’ll make up the rest of it on shows and so forth.” So we went back to Wheeling for a while and we left there and came back down to Kingsport and went out to the radio station without A. P. Carter, just the two of us, Johnny Clark and myself (we’d left Winnie Sisk back in Culpeper). We got down there and we went to the radio station and said, “well, we’re here,” and they said,” oh yeah. Well, we’ve moved the radio station, and we’ve had an awful lot of expenses and we’d just love to have you come on but we can’t pay that weekly salary at all.” So we said, “thanks a lot,” we just wouldn’t be able to afford to stay around, so we drove on without even seeing A. P. Carter. We drove on down through to Knoxville and stopped down there at the Merry Go Round, which was still on WNOX (I guess it still is) and we went there, and I can’t remember the fellow’s name there, the fellow has been running it for years, not Cas Walker, he’s the grocery store man, but the fellow who used to actually run it and produce the program; but we went and talked to him and he said, “we’d love to have you on here, but there’s four bands here already. The country’s just not that strong financially that they can support a fifth band. All the boys can just eke out a living now; if we brought a fifth band in here I just don’t think anybody could make a living out of it.” We went on to Ashville, North Carolina….went to WWNC. They had some television going for them and various things, but they just didn’t have any money, or at least they said they didn’t. I know they had a lot of it but they just didn’t want to have us get any of it. So we left there and went on through to Decatur, Georgia. Actually Wade Mainer was working down in Decatur at the time on WEAS. We went on down there and decided that we ought to stay there for a while; but it was the same story. There wasn’t any money. To this day I don’t think there’s any money in Georgia, ‘cause we sure couldn’t find it if it was there. Luckily we had an Esbo credit card and that’s the reason we’re back up north now. That’s about the only reason. We did sing in Savannah at a place called “The Bam,” I believe it was, to pick up a little pocket money to get us through, and we came back up to Richmond. On the way we heard George Popkins on the air at WXGI, and we heard our names mentioned. He said that if anyone knew our whereabouts they would like to find us, and that they were anxious to talk with us.

So we phoned the station and said, “well, we’re here. What is it you want to talk to us about?” and they said, “we just want to see if you’ll do something for the station.” But they didn’t want the band; they just wanted me to come over and do a disc jockey show for five and a half hours a day, which I did for one week and then decided against it. At that time the band really broke up. Johnny Clark went back to the farm, we didn’t have any work and we had only recorded a few things for Blue Ridge which hadn’t been released yet.

R.K.S.: Oh, when were those records made?

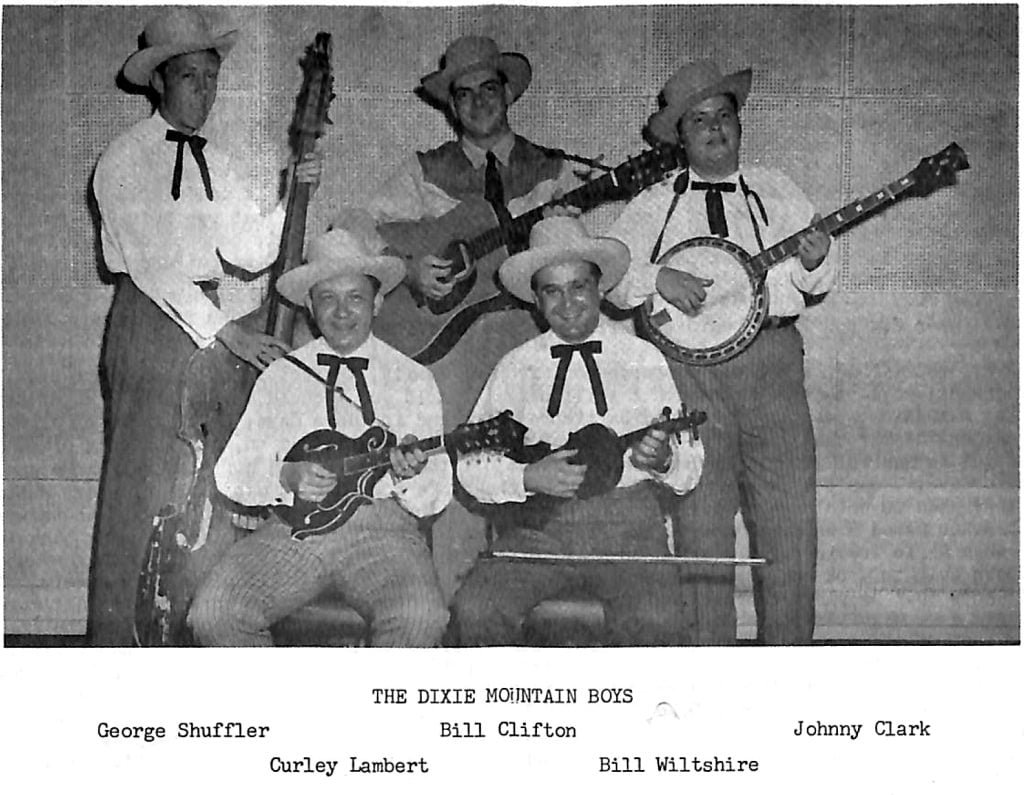

CLIFTON: They were made in 1953, I mean the first one was made in 1953: “Flower Blooming In The Wildwood” and “Burglar” and “Wake Up Susan” were on the same session. A couple of others haven’t been released, like “Little Pal”, “Leaning On The Everlasting Arms” and things like that. We recorded those in ‘53 in Charlottesville at the Speech Department of the University of Virginia. They weren’t released until a couple of years later, if I remember, at least a year later. So anyhow we didn’t have any work as a band, didn’t have any income and X took this job as a disc jockey. I don’t remember what that paid; it was not very well paid, but it was better than nothing, and we hadn’t had any income for a long time, so I thought I’d better take it. Johnny went back up to the farm in Warrenton, and that was the end of the Dixie Mountain Boys for 1953, at least; that was November, no, December of 1953 and…

R.K.S.: Before we leave this subject who else played on those records with you and Johnny?

CLIFTON: Bill Wiltshire from Richmond, Virginia was the fiddler and a fellow named Jack Cassidy played bass, from Bristol, Virginia. He’s been known around Bristol as Blind Boy Jack. He’s a fine singer and guitar picker as well as bass player. Curley Lambert was the mandolin player and Johnny Clark was banjoand tenor singer. Well anyhow, I had this one week in Richmond as a disc jockey and then I went back up to the University to finish up. I needed one more subject that I had to pass in order to get my degree. I went into the Marine Corps in March, 1954. At that point Johnny Clark went with Wilma Lee and Stony Cooper, went back to Wheeling, which was the beginning of their having a banjo player. They’d always had Buck Graves on dobro before then and Buck had left them. So Johnny took over as a lead banjo player. In the Marine Corps I didn’t do a thing except put together a song book. I did take one trip to record up to Baltimore, Maryland. I got George Shuffler to come along and play bass, and Johnny Clark, Curley Lambert and Bill Wiltshire. We did “All The Good Times Are past And Gone” and a couple of other things that weren’t much count, and that’s really about my musical experience in the Marine Corps except to do recruiting programs on local television stations.

R.K.’.: You were never out of the country while you-were in the Marines?

CLIFTON: Yeah, I went to Puerto Rico for two three month periods each year. I was in two years and each winter I’d go down to Puerto Rico three months for exercises, they called them. I had all of three palm trees between me and the ocean and it was fabulous. It was terrific but not much music, very little music. So it wasn’t until I was getting ready to get out of the Marine Corps that I began to think again about what’ll I do about the music. I liked what Mercury Records was doing a lot. I thought it was just terrific what they’d been doing. I thought I’d take a trip over to meet this fellow who Carter and Ralph Stanley had told me about. Dee Kilpatrick, who was the A & R man for Mercury. They said, “you ought to go over and talk to Dee because you know there’s no reason why you shouldn’t be on Mercury records. You’re on records; you might just as well be on Mercury if that’s the one you want to be on.” I thought that sounded right to me, so I took a trip over one weekend. I’d been over visiting with the Carters and took a couple of days leave. I went down to see Dee Kilpatrick in Nashville and took him our Blue Ridge records and said that I wanted to do some other things. He said, “well, can you sing me one of them?” and I sang “Little White-washed Chimney” and he said “yeah, we’ll do that.”

R.K.S.: Well, did’t you in between make a Starday record that had Ralph Stanley and …

CLIFTON: That’s right.

R.K.S.: Now that took place before you made any of the Mercury records.

CLIFTON: But that was the result of my meeting with Dee Kilpatrick. What happened was that between the time I talked to Dee Kilpatrick and when I got out of the Marine Corps, Dee took over the operation running the Grand Ole Opry and left Mercury records. This meant that somebody else had to take over Mercury records and that somebody was Don Pierce. So I wrote to Dee Kilpatrick, I think it was about February of 1957 and said I was ready to record these songs now and could I come down and record them. He wrote back that he was running the Grand Ole Opry and wasn’t involved with Mercury records anymore, and he highly recommended me to Don Pierce who was involved with Mercury records. I got a letter from Don saying that he was very interested in having me do these things, but they didn’t have any money to do them with, so did I want to do them or what. I said yes, and I got ahold of Ralph. Johnny Clark was still with Wilma Lee and Stony Cooper and he couldn’t get away, so I phoned Ralph Stanley and asked Ralph if he would come down and record with me. He said yes he would. Curley Lambert and George Shuffler were working with Ralph and Carter then, so I got Curley and George, and then I had Bill Wiltshire still on fiddle and his brother-in-law, whose name I can’t remember; real nice boy, he still plays around. So the two of them came down to play twin fiddles. We did four songs and I took them out to Don Pierce.

R.K.S.: Can you name them?

CLIFTON: “Little White-washed Chimney”, “Take Back The Heart”, “Gathering Flowers From The Hillside” and “Railroading On The Great Divide”. That particular version has never been released, the one we did on that session. I believe that’s all we did on that session and then we took them out to Don Pierce and Don liked them and said yes he was going to issue them, but he was going to issue them on his label Starday, which he did. The reaction was very good. Lee Sutton up at WWVA began to play the heck out of the first release, which was “Gathering Flowers From The Hillside”, and “Take Back The Heart” was the other side, I believe, but at any rate, he began to play it and he played it a lot. Don began to sell a few records and thought, well it’s pretty good. Meantime, I really wanted to re-record “Little White-washed Chimney” cause I didn’t like the way it sounded on that particular session. I thought it would be nice if I could go down and re-record it, so Johnny Clark got back from a tour that he was making with Wilma Lee and Stony Cooper, and I asked him if he could run down in Nashville and record with me. I didn’t want to bring any other musicians down because I didn’t know how I was going to go or anything. He said, “I can get you a couple of real good fiddlers down here; you don’t have to bring any fiddlers down.” So he got Gordon Terry and Tommy Jackson and he was right; he got a couple of good fiddlers and also he said, “don’t bother to bring a bass player down because there are plenty of good bass players in Nashville.” So we got Jr. Huskey to come in and play. We decided that we needed a bit more rhythm, so Wilma Lee Cooper’s brother-in-law, rhythm guitar player Johnny Johnson, came along and we had a real nice session. After it was over I took it out to Don Pierce and he said, “that goes on Mercury, the whole works!” That was the beginning of the tie in with Mercury. We did one more session for Mercury-Starday, but only half of it came out on record because Don’s affiliation with them fell apart at the seams about that time, and I just went ahead and continued to record with Don Pierce and Starday after that.

(CONTINUED FROM LAST MONTH)

RKS: I guess from then on the history of your recordings is pretty well known. You’ve used varied musicians, both here and Nashville, and fiddlers and some interesting sounds by way of some of the interesting instrumentation Mike Seeger, for instance, has added to the records such as the drop thumb banjo and autoharp. You left a good series of Starday records, some of which we’re still hearing for the first time like that London album.

CLIFTON: You mentioned Mike Seeger. Mike and I had been playing around together a little bit in sort of strange places. We had been singing and Paul Clayton, the three of us formed a trio and we would float on boats down rivers and things and sing to people who were members of historical societies and things like this. We had a pretty good time. We sang at society square dances and this sort of thing up around Baltimore and so it was natural for Mike to fall into the group in the sense that he and I were already playing quite a bit of music together and were good friends. I didn’t really have a band any more, in fact I never have from about 1957 when I started recording with Starday and then Mercury. I didn’t really have a band and yet there was a demand for bands so that every time Don Owens or somebody would phone me and say, “I’ve got three dates for you and can you play them,” I would have a band, but the band varied quite a bit. It was usually Curley Lambert on mandolin and Johnny Clark on banjo…

RKS: This was after Curley left the Stanleys?

CLIFTON: Yes, that’s right. Johnny and Curley and I would have Roy Self on bass (he lived locally here in Washington) and Carl Nelson began to play fiddle with me on shows and then Mike Seeger. When Curley Lambert went back with the Stanleys again as he does periodically, John Duffey and I began to do a lot of things together and it worked out nicely. We did a recording session together, the last one we did for Mercury in which John sang tenor and it was a nice sound.

RKS: Which were the tunes that came from that session?

CLIFTON: “Are You Alone”…and let me see you put me on the spot now. There were five of them, “You Go To Your Church And I’ll Go To Mine,” “Darling Corey”….

RKS: I remember seeing those on Starday but not on Mercury.

CLIFTON: “Are You Alone” was on Mercury on the other side of “Blue Ridge Mountain Blues” but that was the only one that John Duffey sang on from that particular session that came out on Mercury. The other four came out on Starday. I don’t remember just off hand just what the other ones were, but there were five of them on that particular session. So John Duffey was part of the Dixie Mountain Boys frequently on shows. We had an arrangement whereby if John wasn’t working anywhere else with the Country Gentlemen or if he could get out of working with the Country Gentlemen on a particular date; if it was a club night at the Shamrock or something and we had to play a major concert in Newark, N. J. or something John, if he was able to get someone to fill in for him, would come out on the road with me. And so that band was what you would call a pick up band all the time, but it was pretty much picking up the same people all the time. Occasionally when somebody couldn’t play, like when Roy Self couldn’t play, why Tom Gray came down and sat in. The first time that I had Tom was when we were playing in Luray at the park there. Since then we’ve done a lot of work together, but at that time he was new to me and he was pretty new to bluegrass as far as playing on a professional or semi-professional basis.

RKS: Since then you’ve made some travels, spent a lot of time in England, and I gather had some influence on the emergence of old time country music there.

CLIFTON: I don’t know how much influence I’ve had on it, but I’ve certainly watched it grow. It has been a really rewarding experience to be in Briton over the last four years. When we first went to England in 1963 there was very little country music or old time American country music in Briton. There were several reasons for this: Number one, the records are very expensive over there in terms of not only dollar exchange but also in terms of working man’s take home pay. They sell for about the equivalent of $4.50 and the working man takes home about $50 a week so $4.50 represents a pretty good bite out of his weekly wage. So a lot of people couldn’t afford records, couldn’t buy them. Secondly, of course, radio is a tremendous drawback. They don’t play any.

BBC is a monopoly and state run and if they choose not to play any music then they just don’t play any, that’s all. They would go for long periods of time where they wouldn’t have any country music on at all—for six months, eights months, a year—and then they would have Murray Cash on again for 13 weeks, a half hour program once a week, and then after 13 weeks they’d cancel the contract and that would be the last for another year. So you just had to be listening at the right moment or you’d miss it. Third, there wasn’t any place for them to play.

That was another thing, there just weren’t any outdoor parks in Briton. There just weren’t any places for them to play, that’s all. Then shortly after we got over there the folk clubs began to grow. When we got there, there were about 75 folk clubs in all of Great Briton and then when we left there this year there were about 500, so it multiplied by about eight times in that period of time. There’s a lot more clubs now than there were then and they’re all on pretty solid ground. The average attendance in the clubs is about 100-125 people and they pay anywhere from the equivalent of 50 cents to $1 to come in. They would run once every week on the same night of the week. With this $50-$125 that the average club took in they could have a guest every now and then, not every week but once in a while, so this gave an opportunity for those people who wanted to play old time music and country music a place to play, and they could get their expenses out of it and maybe a little money on the side. So it’s been a terrific shot in the arm for it.

Also, we’ve seen it come on the radio over there in stronger form. The last three months that I was in Briton I did a Saturday afternoon program for BBC in which we had quite a bit of country music—not a lot, it was just a half hour program. I would have one guest or sometimes two guests on a program. A typical program was one where we’d have a female singer like Shirley Collins who plays 5-string banjo and the Echo Mountain Boys who are the only full five piece bluegrass band in Great Briton. At least they were the only full five piece bluegrass band in Great Briton until a little bit ago. There is now another group in Tunbridge Wells and there are other groups springing up from time to time now, but the Echo Mountain Boys are the only ones who have had national coverage on the radio and played at the Albert Hall in London and pretty major concerts. This sort of program would be three quarters bluegrass and old time music.

RKS: Did they work under your aegis a great deal of the time?

CLIFTON: No, not really. I’d say 95% of what they do they worked out on their own. They worked it out partially from records, at least they have to use them for a guide. They progressed and integrated and they write their own songs and they’ve just done the biggest bulk of the work on their own with very little help. The biggest help they’ve been able to get has been from incoming groups and artists such as Mike Seeger, The New Lost City Ramblers, Doc Watson, Bill Monroe and his Blue Grass Boys, The Stanley Brothers and Cousin Emmy. People like this have been coming into Briton to sing and they’ve had a chance to see them perform not only on stage but in our living room and places where they could ask them questions about how they get this run or how they do that. I think this helped a lot, where many of us never had this opportunity when we were learning. It’s nice to see.

Bill Monroe made a comment about Andrew Townend here. When I was asking Bill one time when he was over in England last year….actually I think I was telling him about Andrew. I said that Andrew played mandolin by default; that everybody had already formed a group when Andrew came into it and Andrew was the youngest, he was eleven and all the rest of them were twelve or more and that Andrew played guitar at that time and they already had a guitar player so they kept looking at him and said “Why don’t you play something else?- “You know we’ve got a guitar.” So Andrew said “Well, what do you want me to play” and they said, “We don’t have any mandolin or fiddle or anything. Why don’t you play mandolin or fiddle?” So he said “all right” and ever since then he has been. Bill Monroe laughed at this and said that was exactly the reason he played mandolin. All his brothers got to the instruments first and so he had nothing left but mandolin. That was the only thing left to him. And when he heard Andrew play he made the comment that it just hurt him inside, all the years he spent practicing and learning then to see some little fourteen year old boy come along and play like that. Of course Andrew is fifteen now.

RKS: How did you feel when Bill Monroe said that?

ANDREW TOWNEND: Well, it made me feel really good, you know. It means more than all the applause you can get at a concert or anywhere.It really means a lot.

RKS: While you are sitting here in the room with us Andrew is one of the Echo Mountain Boys or will be when he returns to England in September I imagine they’re anxiously awaiting your return too. Have you been pretty happy with the growth of bluegrass as you’ve observed it and been a part of it there in England? Do you agree with Bill’s assessment?

ANDREW TOWNEND: Yes, it really has been coming on a lot. As Bill said the folk clubs are the major help we’ve had because they give everyone a chance to go and play and that’s what you need. As Bill said there are over 500 now and that really is a great help in getting people to play and bringing people together to play and to meet each other.

RKS: Any chance that your group will make a record soon?

ANDREW TOWNEND: I don’t know, I really don’t know.

CLIFTON: You’re working toward it though aren’t you?

ANDREW TOWNEND: Yes, that’s what we really would like to do.

RKS: You could make a tape perhaps and send it to an American producer and have the album released here if there wasn’t sufficient interest in Briton. Have you thought of that?

AIIDREW TOWNEND: No, I haven’t actually Dick, thanks.

RKS: What are your plans for the future Bill? You’ve just been back in the U.S. now for a few weeks and I know you’re studying languages rapidly…

CLIFTON: I’ll have to start back a few months to answer that. A year ago I was traveling (Saralee and the children and I have done a lot of traveling while we’ve been living in Briton). You talk about all these good folk clubs, the folk clubs are just great ten months out of the year, but come July and August every good Englishman is out on his holiday and if you want to play in any folk clubs you’d better go to the places where he’s going for his holiday ’cause that’s the only place where there’ll be any people. It’s a good chance to get away and travel, so we’ve had a lot of opportunity to travel. Another thing I’ve been wanting to do in the summer time when I knew I couldn’t work anyhow in Briton—I’ve been wanting not only to travel but I’ve been wanting to do radio and television and as much live performances as I could do in other European countries that are non-english speaking just to see if I could get any interest in the music. It’s been slow, but we recently did a ten day tour of Denmark and I’ve been on radio and television there a number of times over the past couple of years. There is an interest in Switzerland. I did a radio program there several years ago. And, of course a very strong interest in Germany. Unfortunately I’ve only played to the American Forces bases there which I dread each time I do it and swear I’ll never do it again—because of the interest in the music; they don’t have any. But last summer we took a special trip we went into the Soviet Union for the first time and I realized for the first time in my life that the people there were very much like Americans in many ways. One way is that they sing songs very much like our songs. I heard a female singer on Radio Moscow coming in from Finland who sounded just like Kitty Wells and her song even sounded like Kitty Wells. It was a three chord type song, simple structure, not one of these complicated type English songs. It was a real easy one. The fact is that none of these people have ever heard American music because it’s not available. There are no American or western european records sold in the Soviet Union.. When you get into the Soviet Union a little bit you can’t get any radio stations that play this kind of music. So, it’s quite interesting that this has developed on its own and in very much the same lines that ours has developed. I don’t mean to make it sound like it’s all over the place, it isn’t, but there is a certain thread following through in the Soviet Union which seems to be very similar to our country music. As I say I don’t mean to exaggerate it or make it sound like there’s a lot of it because there isn’t. We only heard this one woman the whole time we were there—six weeks or seven weeks—and that’s the only person who did sing this way.

RKS: Was this a popular song on the radio?

CLIFTON: No, it was more or less a live performance. It was sort of a field type performance in a local area somewhere. I don’t even know where the thing took place. I never was able to find out, although I did a one hour program for Radio Moscow and I asked them at the time if they could check their files and see who this woman singer was, but I was unable to find out. They said she was included with a lot of other singers who were singing from that same area and they just didn’t know which one it was, which I’m sure was true. Anyway it was unfortunate. The trip though opened my eyes a lot because it was the first time I had been in the eastern european countries and Soviet Union areas. I also spent some time in Rumania which again made me very enthusiastic; not their music, but the idea that these people had never heard old -time American music or country music or bluegrass music ever on radio or any place, so that to hear an autoharp played or a country guitar was a novel experience to me and I enjoyed it.

RKS: When you were making these trips to Russia and Germany did you have a bluegrass band or country band?

CLIFTON: Not to these particular countries I’m talking about now I didn’t. The Echo Mountain Boys worked in the Netherlands with me last year in December and January. We did a festival and a couple of half hour television programs in the Netherlands and clubs and things. But no, normally speaking I’ve been working as a soloist for the past four years and all this business about the Soviet Union, Rumania and Hungary and so forth is just that I felt very strongly after having been there that America should do more as a cultural exchange to these countries by sending-country musicians, old time musicians and people who really represent this kind of music best.

I felt so strongly about it that I cancelled two weeks of bookings in October in England in order to come back here. I came back to Washington and I went to the State Department and went to talk to the Cultural Exchange people about coming to work for them so that I could get people like Grandpa Jones and Merle Travis and Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys and the Stanleys and high caliber singers and pickers out to this part of the world. The State Department said that they were terribly sorry that they just couldn’t hire me because the president had just put a freeze on employment and the only way that you could get employed was to come through the usual foreign service examinations and so forth, but there was a way around that. And I said, “Well, what’s the way around that,” and they said that the way around it is to go to work for the Peace Corps. The Peace Corps has no such restrictions. I didn’t know anything about the Peace Corps at all and I thought it wouldn’t hurt me to go and find out. So I went over there and talked…spent a week with them talking and finding out about what made it tick, and decided that I

would like to do that for a few years. I went back to England and talked to Saralee about it and she decided that it was something that she would like to do too. So, we have now committed ourselves to three years in the Philippine Islands with the Peace Corps, working in a staff position, but working basically with the volunteers on various projects that are under way in the Phillipines.

During that three years of course, I hope to play some music but in the Phillipines it will be on a very non-professional basis. If I do anything else it will be in Japan or perhaps Australia or New Zealand, but that will probably beafter the three years. I should like to go down and visit Australia very much. Their country music is just about where ours was 30 years ago and I like it very much. I would like to go down there and spend some time down there, perhaps six months, but I don’t see how I can do that until after we’ve had our three years with the Peace Corps. And at that point, before we come home, I think we might go down there.

RKS: With the Peace Corps then you’ll be teaching essentially?

CLIFTON: No, working with the American volunteers who are basically teachers. Ninety per cent of our program for the Philippines is basically a teaching program, but my work is really with the volunteers. I guess you might say I’m a liaison man between the volunteer and the two governments that he has to contend with—the American government and the Philippine government. I’m a go between; that’s about the best description I can use.

RKS: Will you have opportunities then in that capacity to try to import some of the good American hillbilly bands?

CLIFTON: I sure hope so. That’s one of the things I really want to do. I’ve been talking to a number of people about going out there and one of the ideas that has recently been suggested by a very close friend of our in Briton who is a number one singer in Briton, Bob Davenport, was that we have an annual American country music package and bring in a variety of maybe four or five performing artists. Probably mostly soloists, but perhaps one group, and have a real country music package. It’s a long way to go—it’s 8000 miles across the Pacific and it’s just a little too far to bring people for the amount of work that there is there without working somewhere else and I’m not sure…

RKS: Still in the last ten years or so the word has gotten out, for instance, that jazz is respectable. People like Dizzy Gillespie and Duke Ellington have been making State Department sponsored tours regularly to a lot of countries and so have a lot of other jazz performers. I think someone somehow should convince these people that American country music has an even longer heritage and has lasting qualities that deem it worthy of equal respect, and that at least your has been that it is a highly exportable product to places as divers as the european countries and the Soviet Union and certainly we know of Japan. Every place that there has been any sort of exposure it’s done a lot of good for the country and people seem to be able to recognize it instantly for what it is worth opposed to a lot of middle class America which all you have to do is say the word hillbilly and they turn up their noses.

CLIFTON: The beauty of American country music is the spontaneity of this music. When the music completely loses its spontaneity then some of the charm goes out of it. I don’t mean that it is no longer listenable,because it’s still listenable to me, but it doesn’t have as much charm and this spontaneity is what really excites european audiences and I’m sure it’s what appeals to many of the eastern cultures because their music is a much more studied approach. For example, in India they study the sitar for fifteen years without even performing in front of an audience, frequently because they want to be perfect before they go…

RKS: George Harrison must really be good….

CLIFTON: But these people find it very interesting to hear young people stepping up to play music that haven’t any background for music, just want to play, that’s all, and this spontaneity goes a long way. And it goes a long way to say a lot of things about America which I think is important.

RKS: Well, that about does it I guess, unless you can think of anything we missed or any sort of closing comments.

CLIFTON: No, I haven’t anything further to say really, except that my own personal tastes still run very much to the old time music and that for all of the expansion going on in the field of bluegrass now…to diesel trucks that are running down little cars and this sort of thing…I just hope that somebody is being raised today who is listening to these records who thinks they are just fabulous and will stick up for them in the same way that you and I and the other folks who have been interested in old time music stick up for their era of old time music. I guess I’m just stuck in that one era and I’ll never get out of it.