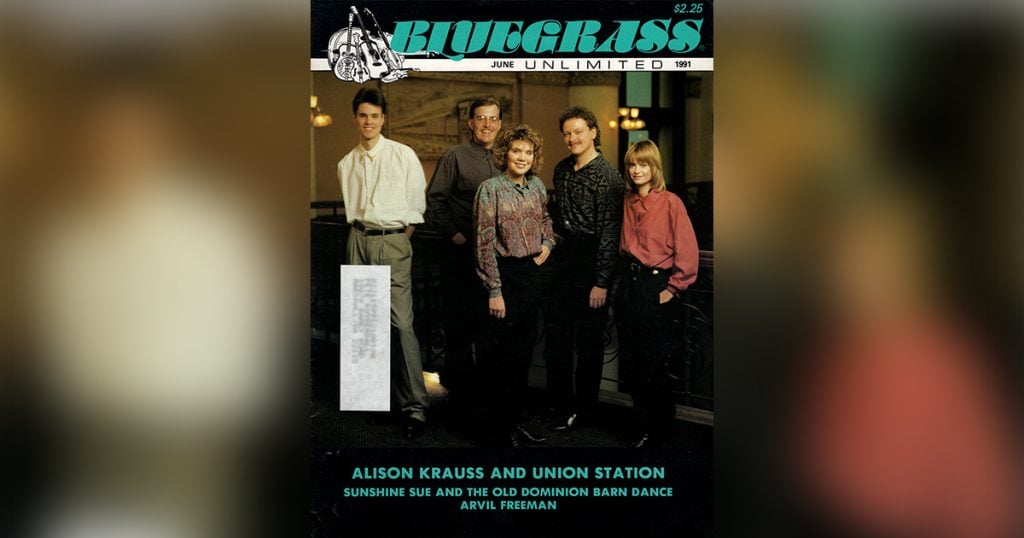

Home > Articles > The Archives > Alison Kruass and Union Station

Alison Kruass and Union Station

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

June 1991, Volume 25, Number 12

“If only all those country (or pop or rock) fans who say they don’t like bluegrass would just give it a listen, they’d love it.”

“If only the mass media would give bluegrass some positive exposure…”

Those of us who care about bluegrass are probably as familiar with these sentiments about our music as we are with “Orange Blossom Special” and “Foggy Mountain Breakdown.” They come up with amazing regularity whether it’s a discussion with people who make their living in bluegrass or conversation with fans at a festival.

Until now mass exposure has frequently meant linkage with comedy (The Beverly Hillbillies, The Andy Griffith Show, Hee Haw!), historical inaccuracy (Bonnie & Clyde—they died before the birth of bluegrass), or what many thoughtful people view as negative regional stereotyping (Deliverance). Even Ricky Skaggs’ stunning success several years ago in making Top-40 country hits of bluegrass songs involved numerous concessions to popular taste—electric lead instruments, drums, etc.

It has thus been with excitement verging on disbelief that in recent months fans have come across stories on Alison Krauss and Union Station in publications like USA Today, Newsweek, Rolling Stone, Musician, Billboard and Time Magazine.

It might be supposed that her recent receipt of the Grammy award for the Best Bluegrass Recording of the year was the cause of this flurry of press coverage. But that would be missing the point. Most of these articles came out far in advance of the award.

It’s not that the national press is just recognizing bluegrass as a valid and noteworthy American music style. These highly-paid professional writers are really listening to Alison. They are tuning in to what bluegrass fans like about her and are helping the general public do the same.

“Subordinated to the group sound as Krauss’s fiddling is, it continues to amaze—airborne one minute, austere the next,” writes Newsweek’s Bill Christophersen. “ ‘Will You Be Leaving’ features a space shuttle of a solo that, just as you’re reaching for the Dramamine, sprouts parachutes and eases into a double-stop.”

“I’ve Got That Old Feeling,” writes USA Today’s David Zimmerman, “is as ‘cutting edge’ as anything around. Krauss’s incredibly nimble, clear voice—recalling a young Dolly Parton—and soulful fiddle convey a passion and vitality that will surprise anybody who expects bluegrass to drone. This is one of few albums bound to please anyone.”

Uncharacteristic warmth like this toward bluegrass by the mass media might lead one to suspect that it was won by gimmicks or by abandoning what fans would think of as “real bluegrass.” No danger. Check out the long lines of diehard bluegrassers trying to get into Alison’s show at Alexandria, Virginia’s, showcase club, the Birchmere, or the wildly excited audience responses at the nation’s major festivals from upstate New York’s Winterhawk, to Colorado’s Telluride to California’s Strawberry Music Festival.

Yet her group can also knock out country fans on Hee Haw! or on the Grand Ole Opry, where the group has been invited back half a dozen times in recent months. It can win over New York City sophisticates at the prestigious Bottom Line. It can even sell out a thousand seat auditorium at Maryland’s (Goucher College) on a double bill with a New Age music group.

Alison’s appeal is all the more remarkable because it is based not on glamour, a fancy stage show, sexy outfits, cuteness or any of the other show business tricks you might think a young female band leader might need to employ to gain attention.

Onstage there is a sense of earnest focus on the music coupled with evident delight by the musicians in one another’s musical contributions. Alison’s voice has a wonderful clarity and precision which appeals to a broad range of listeners. Her instrumental work is not only technically excellent; it is also beautifully creative and exciting even to someone who has listened to decades of the great bluegrass fiddlers.

Alison is by no means a solo performer with a few faceless backup musicians. She loves playing with people who challenge her musically. And she loves her present band. When asked to name the people in bluegrass music who most inspire her, she first names the members of her band. These are Alison Brown (banjo), Tim Stafford (guitar), Adam Steffey (mandolin) and Barry Bales (bass). By the standards of earlier generations, it would seem an unlikely mix of backgrounds.

Can we—just for fun—imagine that a major motion picture is going to be made about a young bluegrass group? “So who are these characters in the band,” the producer asks the script writer? “Are they believable?”

“Well,” comes the reply, “there’s this great girl fiddle player from Illinois, named Alison, who sings great and this other girl, she’s named Alison too. Alison number two is really little and slender and has this real strong solid way of playing the five-string banjo. She’s actually a Connecticut-born Harvard graduate who leaves investment banking for a career in bluegrass music. Then there’s these three guys who played together in this university bluegrass program at East Tennessee State University …”

“Irv, Irv, hold it baby!,” croons the producer. “Listen man, I love you, but this has got to be believable. Bluegrass in college? Women investment bankers? This script has got to have legs!

“How about going back and coming up with something really authentic- sounding—maybe a retarded clawhammer banjo player who makes up “Dueling Banjos” in three minutes out in the Ozarks with some guy he never met before? Or maybe a hillbilly who strikes oil and moves to Beverly Hills?”

The truth about Alison Krauss and Union Station does, perhaps, strain credulity more than a little. A brief chronology might give a few hints of what an unlikely success story the band represents:

Age 12: Alison starts listening to bluegrass seriously.

Age 15: Records her first album for Rounder Records.

Age 17: Plays on the first of several Masters of the Folk Violin Tours with the likes of Kenny Baker, Michael Doucet, Joe Cormier, Seamus Connelly and Claude Williams.

Age 18: Wins 1990 Grammy nomination for her second Rounder album, “Two Highways.”

Age 19: Wins 1991 Grammy award for her third Rounder album “I’ve Got That Old Feeling.”

Her first video goes to #1 nationally against all major label country videos on the CMT network. It wins the Video Challenge (in which viewers vote for their favorite) several weeks in a row.

Wins International Bluegrass Music Association’s female vocalist of the year award. (Most of her fellow award recipients have been playing professionally considerably longer than she has been alive.) She also captured SPBGMA’s 1991 Female Vocalist Of The Year (overall) at their Nashville National Convention this past February.

The song “I’ve Got That Old Feeling” holds the number one position on the Bluegrass Unlimited National Bluegrass Survey for several months. The song “Two Highways” from her previous release was the #1 song on BUs National Bluegrass Survey debut chart in May of 1990. Alison sings harmony on Dolly Parton’s upcoming CBS release.

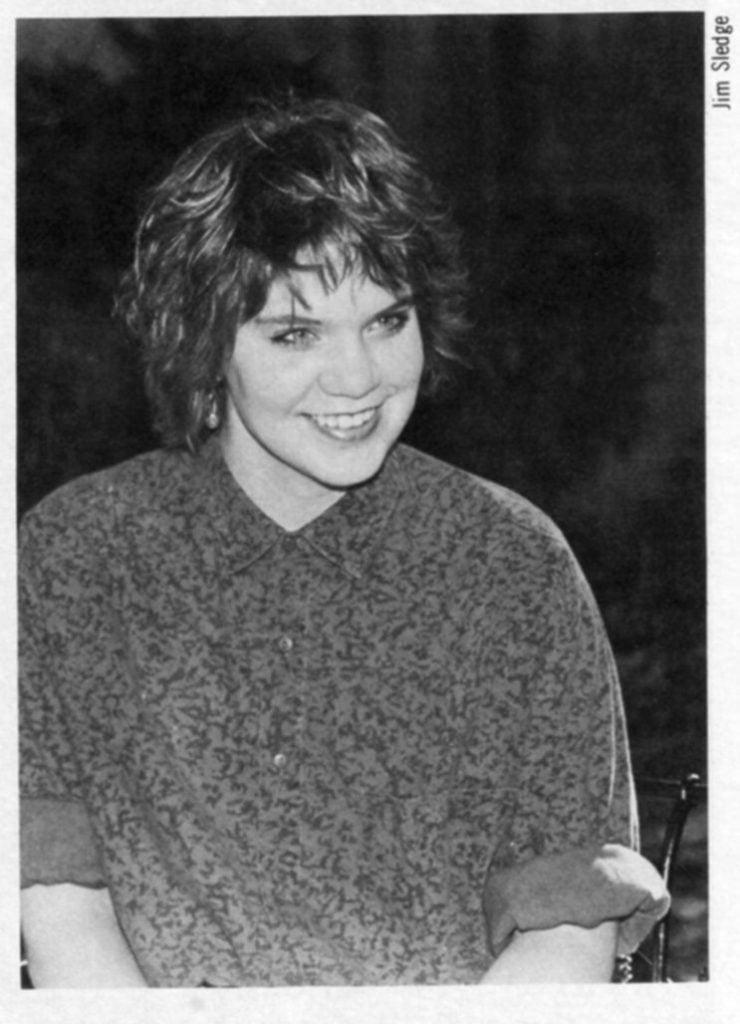

Alison Krauss

Alison Krauss was born in 1971 in Decatur, Illinois, and raised, after the age of three, in Champaign. There was no bluegrass music in her world for many years.

“My dad went around the house singing in an operatic style,” Alison remembers smiling. “Things like “I Wish I Were A Rich Man” from Fiddler On The Roof. My mom played some fingerpicked folk guitar stuff and sang harmony. The first music I liked was rock and roll, disco and musicals like Grease and Saturday Night Fever,

“I did like Hank Williams, Sr., singing ‘Honky Tonk Blues’,” she laughs. “When I was five or six my brother, Vik, dressed up like a girl; I got dressed up like a guy and we’d dance to it. It was the last song on the album, but we were too little to realize we didn’t have to play the whole record to hear it. So we listened to that whole album over and over, just for that one tune!”

One simple incident at school may well have set the course of Alison’s life. There was a string program at her school. While still in kindergarten Alison heard the violin and decided that’s what she wanted to play. At the age of nine, Alison went to her first fiddle contest. She had gotten a book of fiddle tunes and had begun learning out of it.

“It was fun,” remarks the entertainer. “I got an outfit—a jumpsuit thing with shorts. This is so funny—my brother Vik thought it looked too fancy for a fiddle contest, so he tied it to the back of his bike and dragged it around for a while!”

Alison came in fourth for the “12-years-and-under” category. It was also the first fiddle contest for another young Illinois fiddler named Andrea Zonn (later with Union Station, the Big Dogs and Vince Gill, among others). Andrea won second place.

“The contests in our area weren’t strict like the ones in Missouri or Texas,” says Alison, “and they weren’t so competitive. They generally went to whoever didn’t squeak the most.”

The contests that really fired Alison up came a little later—the more competitive ones. The first of these was in Elizabethtown, Kentucky, where she heard fiddlers Jimmy Mattingly, Jim Wood and Ed Karns. “Sharon Winters (see BU, December, 1983) was there in the under-18 category. It was great,” enthuses Alison. “I had never imagined how good it could possibly be!”

When she was about eleven, an incident at the famous Weiser, Idaho, contest got her fired up to further improve her playing. “This one girl came up to me,” recalls Alison, “and said, ‘Don’t worry. My bowing used to be just as bad as yours.’ Immediately I decided, ‘Not for long, honey!’ ”

Alison promptly got a tape of the girl’s favorite fiddler, Bart Trotter. She then proceeded to work up the very best version she could of the tunes on it. For Alison, it turned out to be a major motivational breakthrough.

As time passed, Alison got to do a little square dance fiddling and some work with a country band. She entered a vocal contest and found she liked to sing. For a time her family—mother, father, brother and herself—played together in Kiwanis Clubs. “It was banjo, fiddle and bass; my Dad never did learn how to play the guitar,” laughs Alison. “It wasn’t bluegrass, though. We did stuff like ‘Jamestown Ferry,’ ‘Good Hearted Woman’ and so on.”

Alison was about twelve when she started really getting excited about bluegrass. “It was mostly J.D. Crowe and the New South, Ricky Skaggs and Boone Creek and Tony Rice,” she recalls. “When I got listening to it I was going crazy. I had never heard stuff like that before!

“I loved Ricky Skaggs’ high singing,” she goes on, “and the timing—it’s hard to say exactly what it was that got me. I listened to Tony Rice’s ‘Manzanita’ album until my brother knew all the words!”

John Pennell had been playing bluegrass with Andrea Zonn and her dad. John left to form a new band which became Silver Rail and Alison joined it. Francis Bray, of the legendary Bray Brothers, lived in Champaign at the time and would sometimes play bass with them. “We played all the stuff off the Bluegrass Album Band recordings,” she recalls.

After two years with Silver Rail, Alison moved to an Indiana group called Classified Grass, with which she’d played from time to time. John Pennell started another group, Union Station. Andrea Zonn played with them for a time, then left for a job at Opryland.

Alison replaced Andrea. Before long, the band began to be a major source of musical excitement and inspiration. “When music sounds good to me,” says Alison, “is when you can’t wait to hear what the person standing next to you is going to play. That’s how it was when Dave Denman and Mike Harman joined Union Station.”

The band did what aspiring young bluegrass bands do—a few festivals, a couple of clubs in town. A few fraternity houses. What fifteen year-old aspiring musicians don’t usually get, of course, is the chance to be the featured performer on a nationally distributed label.

“One day, we got a demo in the mail from a group called Classified Grass,” recalls Ken Irwin of Rounder Records. “Most of the demo sounded pretty good, but it didn’t really knock me out. It’s the sort of thing that makes you say, ‘Let’s see what’s happening with them a year from now.’ ” Then Ken came to a gospel song with a female lead vocal. It was Alison. Suddenly Ken paid extremely close attention. He was very excited by what he heard.

Ken found out that Dave Samuelson of Puritan Records had heard the band in person. Dave was extremely enthusiastic about Alison, especially about her potential with the fiddle. “She could be anything she wants to be,” Dave told Ken. “She could be another Stephane Grappelli.” Ken called her. “She was extremely professional,” he smiles. “She must have been about thirteen at the time, but it was Alison, rather than her parents that I dealt with each step of the way.”

Before long Ken—after consulting with his partners at Rounder, Marian Leighton-Levy and Bill Nowlin—was able to call her back with a two-part offer: (1) To play at the prestigious Newport Folk Festival and (2) to do an album with Rounder.

“We had never even heard her in person before we signed her,” acknowledges Ken. “That’s extremely unusual. In fact it just about flies in the face of all rationality!”

The rewards of Rounder’s gamble were, however, not immediately evident. Alison’s first album—“To Late To Cry”—did not instantly take the bluegrass world by storm. “There was a lot of interest and curiosity and a certain amount of word-of-mouth,” says Ken, “but it built gradually. The bluegrass community was slow to appreciate women vocalists then. In fact, we still get occasional cards from someone who says: ‘Women can’t sing bluegrass.’

“Things have changed a lot since then, though,” he reflects, “At the last IBMA convention quite a few of the bands had female lead vocalists.” By the second album, with its Grammy nomination, some real momentum was building. Winning the 1991 Grammy has further accelerated things.

Perhaps Alison’s success has helped pave the way for other young women singers in bluegrass. It seems clear that, as Ken puts it, “Alison is the person who has done most in recent years to raise the profile of bluegrass music in the outside world.”

Despite the massive attention she is getting, Alison is remarkably modest about her abilities. Complimented on her fiddle work, she laughs, “I’m just trying to sound like Stuart (Duncan).” Asked about her favorite musicians, she comes up with a seemingly endless list including Ralph Stanley, Larry Sparks, Rhonda Vincent, the Cox Family, Shawn Colvin, Stuart Duncan and her present band members. (“I hate to have to take a break after Adam’s picked one,” Alison adds, with a smile.)

Then she thinks a moment and adds to the list: Lynn Morris, Tom Adams, Dudley Connell, Del McCoury, Chris Jones, Dan Tyminski, Ron Block, Maura O’Connell and Jonathan Edwards.

Alison is also extremely appreciative of the songwriters who have contributed to her career, especially John Pennell, Nelson Mandrell and Todd Rakestraw. “People always ask me where I found John Pennell,” she asserts. “Shoot—I grew up with him. He was nice enough to let me play in his band!”

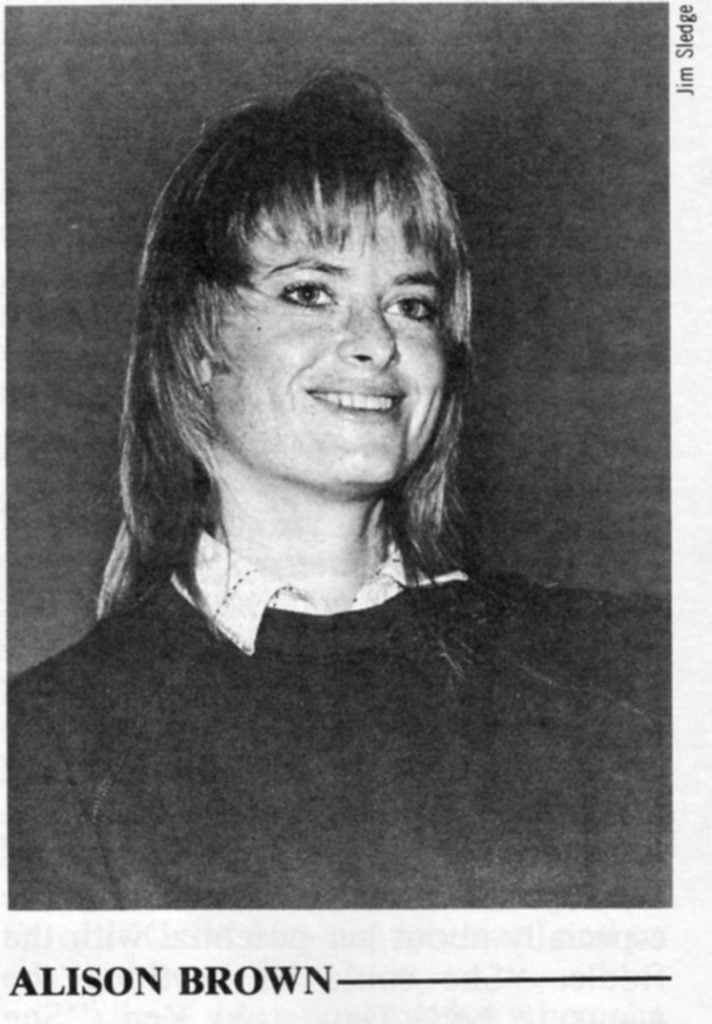

Alison Brown

The lovely and authoritative banjo work in Union Station comes from the steady hands of Alison Brown. She is equally at home with traditional or progressive bluegrass and also can play some beautifully soulful guitar.

Alison Brown’s national recording debut was an impressive one. “Pre- Sequel” (Ridge Runner Records) was a standout instrumental album highlighting Alison on banjo and Dobro and her musical partner, Stuart Duncan—now with the Nashville Bluegrass Band—on fiddle, mandolin and guitar.

Alison was barely out of high school at the time. Yet the music on the album was of such quality that Byron Berline, in his liner notes, was moved to comment, “Alison and Stuart have accomplished more with their music than many do in a lifetime.”

Born in 1961, Alison spent her early years in Stamford, Connecticut. Her parents had bought each other guitars and were learning a little folk music on them. At the age of eight, Alison started learning too.

By the time she was eleven, her guitar teacher, who also played banjo, had let Alison hear the Flatt and Scruggs “Foggy Mountain Banjo” album. She decided to switch instruments and has stayed primarily with the banjo ever since.

After her family moved to San Diego, California, Alison first heard a ten-year-old Stuart Duncan in a young group called the Pendleton Pickers. The group was quite good; Alison recalls that their music won them an appearance on the Grand Ole Opry at one point. She was exceptionally impressed with Stuart’s ability.

Before long Alison became part of a thriving bluegrass scene in the Los Angeles area, commuting frequently from San Diego with the help and encouragement of Stuart’s father. “Berline, Crary and Hickman were based there; so were the Dillards,” she recalls. “There was a lot going on.”

Alison listened to Flatt and Scruggs and Ralph Stanley, but she also paid careful attention to progressive music like that of the David Grisman Quintet, Russ Barenburg and Tony Trischka. Tony’s “Banjoland” album was a special favorite of hers. “The California bluegrass scene tends to be more progressive in the southern part of the state,” she explains, “more so than in northern California or on the east coast.”

Studying at Harvard University in the early 1980s Alison continued her musical interests with the progressive Boston-based band, Northern Lights. Although she loved music, she didn’t envision performing for a living. On graduating from Harvard Alison decided to do postgraduate work at UCLA and rejoin the California bluegrass scene.

To her intense disappointment, the vibrant bluegrass community she remembered had mostly dissipated. At first Alison considered trying to get work in the entertainment business. She did an internship at a major record company but soon changed her mind. “That really turned me off,” she asserts. “People were sitting around in their offices, doing no work and getting high!”

Alison completed her degree work at UCLA and went to work for Smith Barney as an investment banker. After two years in the financal world it became clear that this was not what she wanted either.

“When you start they tell you they expect you to work hard, which is fine with me,” explains Alison. “But what they mean is they want you to work all the time—fourteen to fifteen hours a day—eighty hours a week. They don’t want you to have any sort of outside interests or activities.”

Alison finally decided to take six months away from the job. She wanted to work on a new album of her own music, but she had no fixed idea of what she’d do for a living. As good fortune would have it in January, 1989, she got a call from Alison Krauss and has been a member of Union Station ever since.

(Note: For those who wish to hear the progressive side of Alison Brown, check out her new Vanguard release of original banjo tunes. Produced by David Grisman, it’s called “Simple Pleasures” and features the playing of Grisman, Alison Krauss, Mike Marshall and others.)

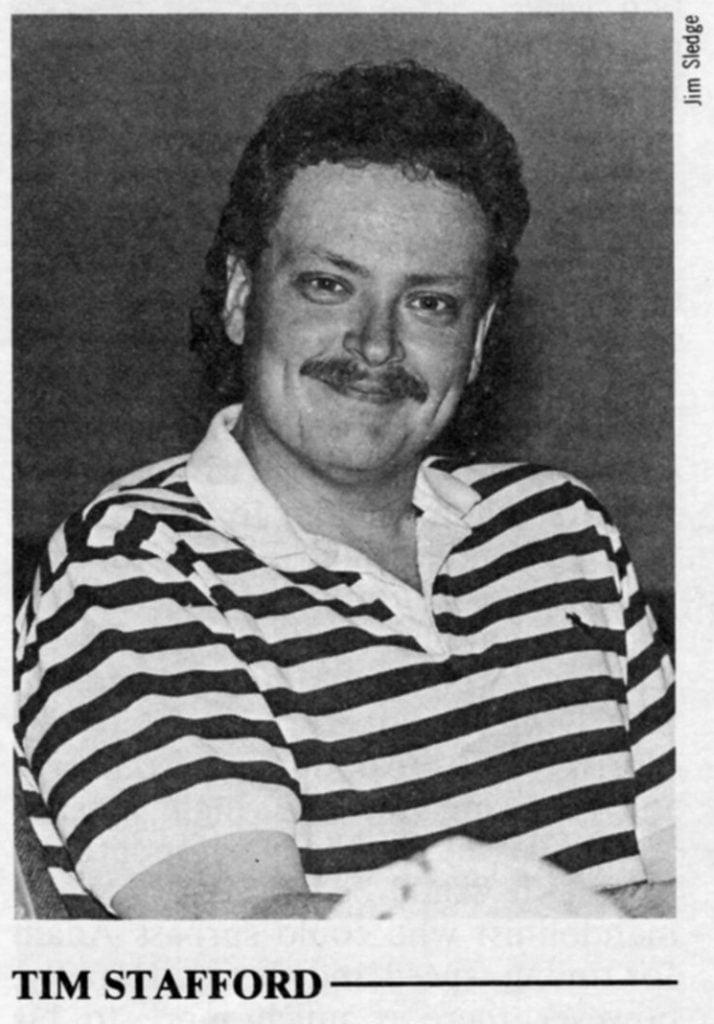

Tim Stafford

Tim Stafford, like Adam Steffey and Barry Bales, got started in bluegrass in East Tennessee. Along with Adam and Barry, Tim played and recorded with Kingsport’s Boys in The Band and with the East Tennessee State University Bluegrass Band. The three were also founding members of the well-respected group, Dusty Miller, whose 1990 debut album on the June Appal label made quite an impression on a large number of bluegrass fans.

Tim has made a considerable mark in East Tennessee both as a musician and by his work for East Tennessee State University’s Center For Appalachian Studies (CASS). He hosts his own bluegrass radio show and cohosts the region’s popular “Bluegrass Heartland” public radio series heard on WETS-FM Johnson City and WWNC Spindale, North Carolina.

Tim has done production work on various albums including those of the ETSU Bluegrass Band, country singer Kenny Chesney and Dusty Miller. Tim also produced an excellently researched booklet and album released by CASS called Down Around Bowmantown which chronicles some of the fine music played over the past forty years in East Tennessee by little known local players.

In addition, Tim played a vital role in securing for East Tennessee State University the Barnicle-Cadle Collection which contains a wealth of historic privately-made disc recordings of such important folk artists as Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly and others.

Despite his various music-related activities, Tim’s greatest love is playing. His exceptional guitar work is rapidly gaining widespread recognition. Imaginative and complex, Tim’s exciting solos combine his own approach to crosspicking with conventional flatpicking. Despite his impressive technique, there is a feeling of spontaneity and genuine emotional connection with each song or tune.

Tim was born into bluegrass music’s East Tennessee heartland, only a few miles from the A.P. Carter Family’s homeplace. The Stanley Brothers were born nearby; so were Jim and Jesse, Jimmy Martin and Doyle Lawson. Flatt and Scruggs, Charlie Monroe and Mac Wiseman had lived and worked in the area early in their careers.

For thirteen years, however, Tim had no idea of what bluegrass was. His taste, in fact, ran first to the Beatles, the Monkees, Dick Clark’s American Bandstand, etc., then to Chicago, Creedence Clearwater and Santana.

Many area musicians of an earlier generation would commonly start out on a cigar box guitar or homemade fiddle. Tim’s first musical exploration was a Moore’s potato chip cannister struck with a Tinkertoy stick. By age twelve he graduated to a real drumset and seemed on his way to being a rock drummer.

Then, at age fourteen, his life changed. As with Alison Krauss, the crucial moment occurred in school. Tim had sung in the Sunday school choir all his life and had thus gravitated—along with some friends—to the high school choir. One day in the choir room he heard a couple of guys picking guitar and mandolin and singing bluegrass songs together. Although he’d never heard anything like this before, Tim found himself asking if they wanted someone else to play with them.

A cheap banjo was Tim’s first bluegrass instrument. This was the 1970s. Melodic style banjo was what excited Tim and his budding musician friends. Bill Keith, Alan Munde and Bobby Thompson were the players Tim listened to. The Country Gentlemen and the Seldom Scene were “in.”

Older forms of bluegrass were, in Tim’s mind, linked with derogatory Appalachian stereotypes: Flatt and Scruggs’ association with the Beverly Hillbillies TV show; the silliness of Hee Haw!; the retarded kid playing “Dueling Banjos” in the film Deliverance. The Seldom Scene’s parody of Jimmy Martin’s “Hit Parade Of Love” reinforced Tim’s impression that traditional bluegrass was pretty dumb stuff.

Then all of a sudden, Tim had a revelation. He heard a few cuts on the radio from the debut album by the New South with J.D. Crowe, Tony Rice, Ricky Skaggs and Jerry Douglas. At once Tim saw how elements of traditional bluegrass and progressive playing could interact to produce music that had both feeling and musical excitement. And, based on Crowe’s example, Tim realized that there was much more to banjo playing than melodic scales.

Tim soon switched over to guitar, incorporating, in his own unique manner, a number of the ideas he’d learned—and subsequently discarded—from chromatic banjo playing. At the same time, his new appreciation for straight-ahead bluegrass led him to fashion an individualistic style that worked beautifully with traditional material as well as with contemporary tunes.

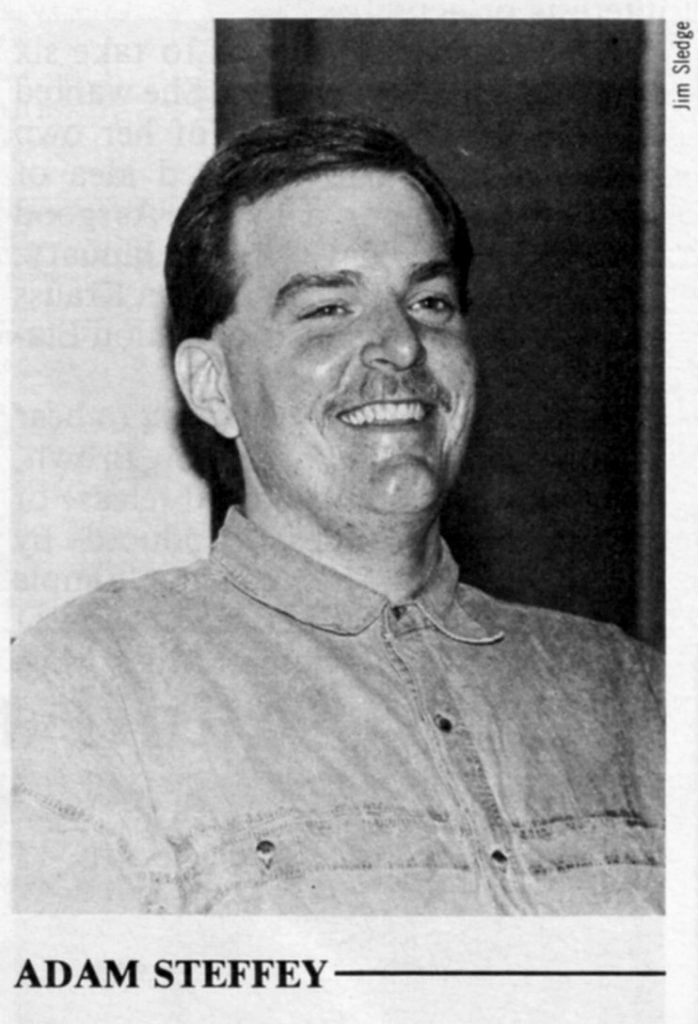

Adam Steffey

Adam Steffey is another of the new bluegrass generation’s major talents. Only those who have not yet heard Adam could fail to appreciate the first photo of him to appear in a national publication. The picture (in Bluegrass Unlimited, May, 1988, shows mandolin master John Duffey “taking notes” with simulated pad and pencil while Adam rips off an explosively hot break during a concert.

Allowing for the high musical standards set by today’s top professionals, it would be difficult to find a mandolinist who could surpass Adam for timing, speed and clarity. Happily, however there is much more to his playing than technical skill. Adam’s ideas are, like Tim’s, quite original, often a little surprising and always in keeping with what the particular song or tune needs.

From Adam’s manner, speech and awesome musical ability you might also figure he is in the “raised-from- the-cradle-on-the-bluegrass-and- nothing-else” category. He speaks with the same accent and understated good humor as many rural East Tennesseeans. His playing, as noted above is not only technically impressive but also reflects an innate sense of what is right for a particular tune.

Adam, however, was raised in an itinerant military family and spent his first ten years moving around from Norfolk, Virginia (where he was born), as far away as Hawaii. Adam’s father sometimes listened to country music on the radio, but records weren’t played at home. “Dad still goes around the house singing anything from ‘There’s A Tear In My Beer’ to Pavarotti,” grins Adam. “He doesn’t care who’s listening!” His mother played organ and piano, chiefly church music.

Adam’s great musical inspiration began in 1975 when his father retired from the military and the family moved back to his mother’s home area in East Tennessee. “My great granddaddy, Preacher Tom (Poppy) Carter was a circuit-ridin’ preacher who also wrote poems and songs,” explains Adam.

“My granddaddy Fred Carter—he’s June Carter Cash’s cousin—told me about seeing A.P. Carter drive up to Poppy’s house in a horse and buggy and then sit on the front porch and write things down in a notebook.” At other times A.P. would bring along a wind-up Victrola (Poppy’s family had no electricity) to play Carter Family records for everyone.

Fred Carter took his grandson to shows at the A.P. Carter Fold in Hiltons, Virginia, where Adam found his attention riveted on young mandolin players like Marty Stuart and Dale Reno. Adam got the Lost and Found’s first album and listened to mandolinist Dempsey Young over and over again. “When I heard the mandolin, whether it was picking or chording,” reflects Adam, “I knew that’s what I wanted to do.”

But Adam’s interests in music weren’t single-minded. He remembers once leaving the local record store with two albums. One was Mac Wiseman; the other was Lynyrd Skynyrd. In high school Adam played trombone. “We had marching band, concert band, jazz band and pop band,” he recalls, “and I played in all of them. I really enjoyed band; it was a big social thing. I learned a lot about music that way—things that have helped me since.”

High school was also where Adam met friends he could learn bluegrass with. Local bands he played in the next few years included Jerusalem Ridge, Bluegrass Edition, Blue Plate Special (with former New South guitarist Glenn Lawson) and The Boys In The Band. At times he would play with Larry Sparks when Larry came to the area. During his college years Adam played with the East Tennessee State University Bluegrass Band.

In his senior year Adam left school to work full-time with the Lonesome River Band. He later joined Tim and Barry Bales in Dusty Miller and subsequently, in the summer of 1990, became a member of Union Station.

“At one time,” Adam reflects, “I was listening a lot to the David Grisman Quintet. For awhile I played David’s records 50 times to each time I played Bill Monroe’s. Now, though, my tastes are more toward traditional bluegrass. For example, Flatt and Scruggs—they had incredible timing, like a metronome, but not mechanical. Like Barry says, along with Monroe, they’re the fathers of bluegrass.”

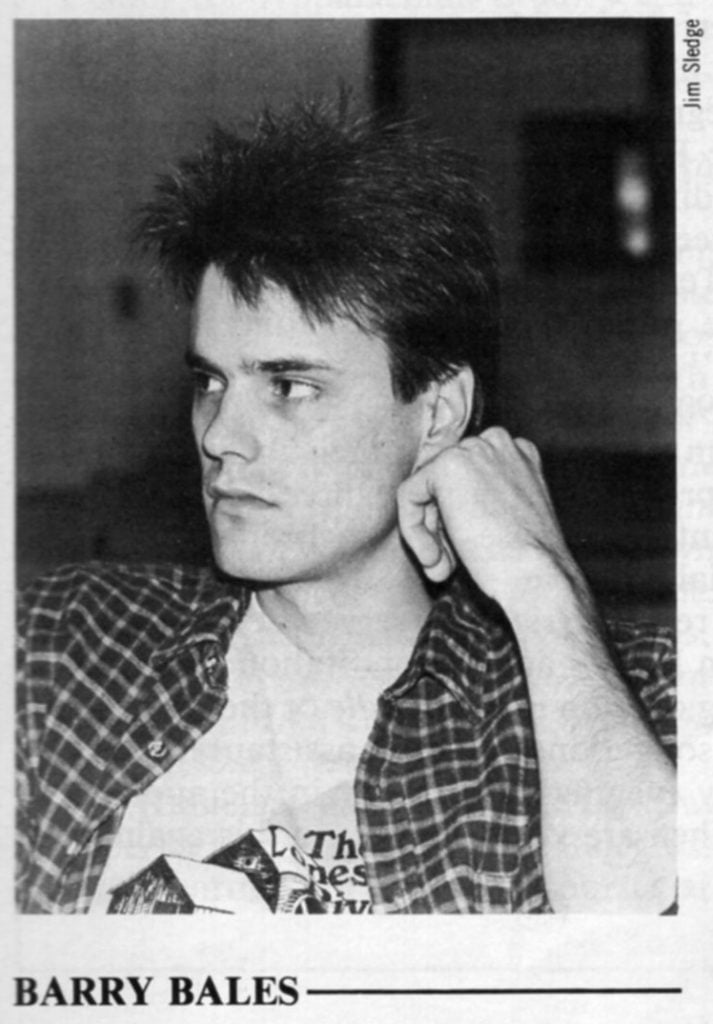

Barry Bales

Not too long ago WKRN-TV Nashville decided to do a four-part feature on mountain music in the East Tennessee region. Accordingly the station’s video crew undertook the five-hour drive to Johnson City where they filmed the ETSU Bluegrass Band in concert at the city’s renown listening club, the Down Home. The following day they continued videotaping on the university campus as they wanted to cover a band rehearsal as well.

After watching each of the band members in action, the director decided that one of the four segments should focus on the group’s Dobro player, Barry Bales. A third videotaping session was arranged thirty miles away in Kingsport at the Bales’ family home. Barry and his father played together for the camera and shared their perspectives on bluegrass music and a future career in it for Barry.

Despite a quiet and unassuming manner in speaking with strangers, Barry’s steady focused approach to performing—as well as his impressive musical ability—regularly wins him this type of approving attention.

During his years in the ETSU Bluegrass Band, Barry showed that he could do a first-rate job onstage with a variety of instruments—Dobro, banjo, lead guitar or bass. As Union Station’s bass player, Barry is an animated driving force, his moving bass lines contributing importantly to the group’s sound.

Unlike the other members of Union Station, Barry grew up in a home where country music held a special place from the start. Ever since early childhood Barry remembers his father pulling out the guitar and singing with it.

“Dad never listened to records 24 hours a day, though, like I do,” remarks Barry. “We didn’t have a lot of bluegrass albums. They were mostly western swing and what I call ‘honest- to-goodness country’ like George Jones and Buck Owens.”

At the age of eight Barry had started trying to play his father’s guitar. At ten years he took a couple of six-week instruction sessions at a nearby adult education center. “For months Dad had to make me practice,” recalls Barry. “Then suddenly I started picking the guitar up on my own. All at once it seemed to come pretty easy.”

In the following years Barry’s primary interest shifted among banjo, Dobro, acoustic guitar and bass, each of which he played, at various times with the ETSU Bluegrass Band. He also did a little sixties rock music with a local group on electric lead guitar.

However, Barry’s commitment to the bass grew as he played, along with Tim and Adam, in the Boys In The Band and later with Dusty Miller. In Union Station he seems very well-pleased to continue his musical growth with the instrument.

Union Station And The Future

It would be hard to find a group with greater promise for future success and potential for bringing new fans to bluegrass. Of special interest to those of us concerned about the “graying” of the bluegrass audience is the youth of the crowds Union Station frequently attracts.

There is an upcoming tour with Ricky Skaggs, a couple of overseas ventures—to Japan and the Scandinavian countries—possible collaboration with rock singer Michelle Shocked, a new video to be shot in California, a single release as well as a new album and much more.

There is also the pressure to live up to people’s expectations, the rigors of road tours and the psychological and physical wear and tear that all musicians face. “Alison Brown tells me I just ought to sleep,” remarks Alison Krauss, “but, there’s no timel”

When you see this group in person, you catch some of that urgency—that there’s nothing in the world that matters more than just playing for the pure joy of it. And when musicians this exceptional feel that way, it can make for some wonderful music!

Share this article

2 Comments

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Wow, this was amazing. I saw Alison at the Birchmere in 1991 and many times thereafter.

What memories!!

My family, wife and three kids listened to Allison Krauss and Union Station for years. We traveled to St Louis and Nashville to hear them live. Last night 07/17/2022 my now young adults were home and we sat and listened to Allison Krauss and Union Station music. What a fun a joyful time we had. At the end of the night my family prayed for each of them.

Each person was a big star to us. I am not certain why they are not performing together. I am sure their is a reason. However, the group has brought so much joy to me and my family that it is hard to accept.

The style and music was so great.

Last I would like to hear Allison Krauss sing Friends are Friends forever by Micheal W Smith.

Tim Martin

[email protected]