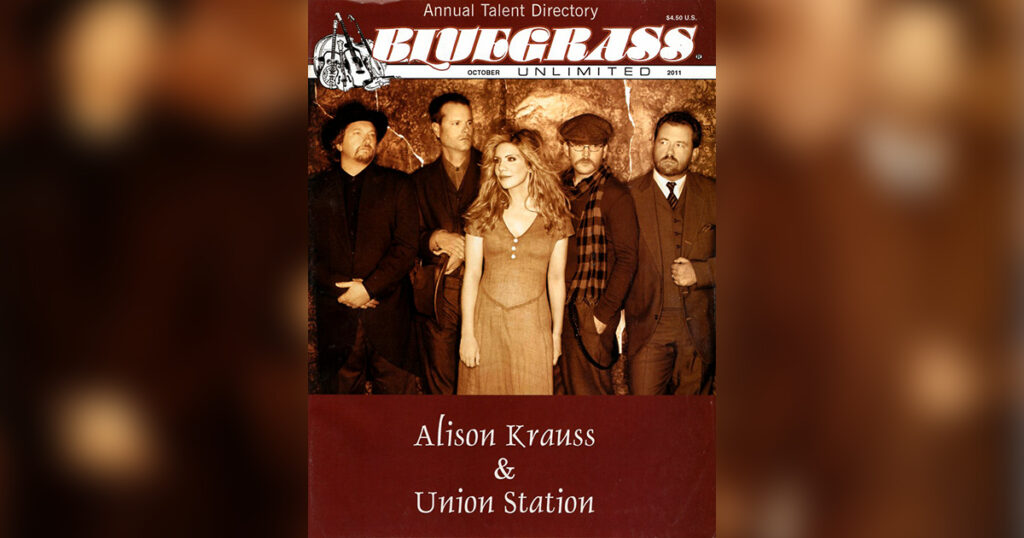

Home > Articles > The Archives > Alison Krauss & Union Station—Flight Plan Paper Airplane Lands AKUS Back On The Bus

Alison Krauss & Union Station—Flight Plan Paper Airplane Lands AKUS Back On The Bus

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine October 2011, Volume 46, Number 4

When rock’s Golden God met the Grammys’ all-time winning woman, he had something on his mind. “My first conversation with Robert (Plant) in person was about Ralph Stanley,” Alison Krauss says, sipping tea in the kitchen of her Nashville home. “I loved that. Robert’s just a music fan and he loves traditional music and he loves learning about that lifestyle, the way that people are living, the work. And he talked about Ralph and, back in the ’70s, driving through the Appalachian Mountains and listening to Ralph.”

Welcome to the musical world of Alison Krauss, a place wide enough to encompass the leader of Led Zeppelin, rock’s original heavy metal band, taking a break from the excesses of stadium superstardom for some bluegrass tourism, driving through the mountains, singing along with cassettes of the Clinch Mountain Boys. Sex, drugs, and forward rolls?

Raising Sand, the 2007 album they made together, was just as surprising, mixing Plant’s exotic musical atmospheres with the deep traditional roots of Alison and visionary producer T-Bone Burnett, best known for the O Brother, Where Art Thou? soundtrack. Raising Sand sold more than 1.26 million copies and added six more Grammys to her arsenal, now totaling 26, more than any other female artist/producer. But like every note Alison Krauss has played or sung in her 28-year career, it all grew from bluegrass.

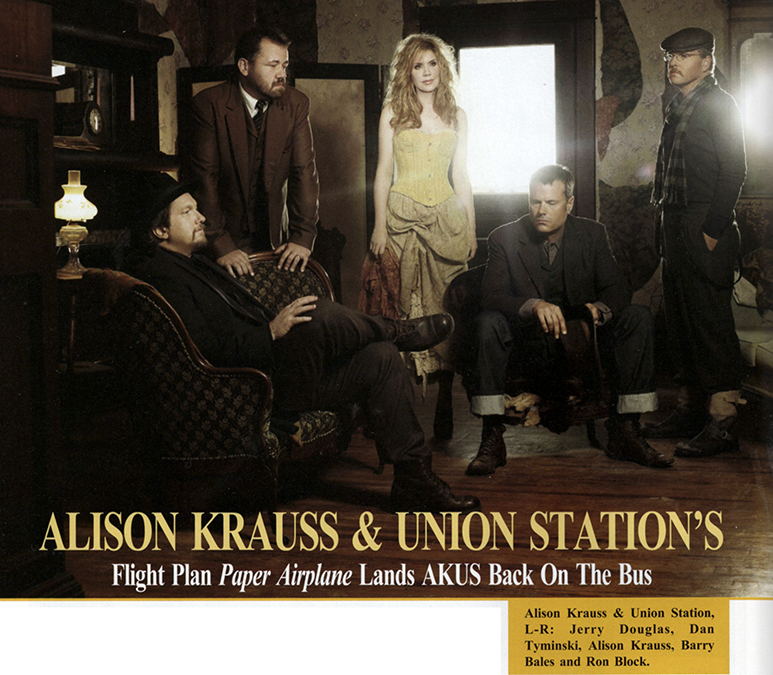

A follow-up was begun in 2009, but the chemistry was gone and the album scrapped, clearing the way to return to her first love. Union Station. When Alison Krauss + Union Station released Paper Airplane this Spring, it was seven years since Lonely Runs Both Ways, AKUS’s last studio project. In between, she’d also sung with James Taylor, had a hit single with ’80s rocker John Waite, and produced Alan Jackson’s Like Red On A Rose. The rest of the band—reso- guitarist icon Jerry Douglas, guitarist/ mandolinist Dan Tyminski, banjo player Ron Block, and bassist Barry Bales—had all been busy with outside projects. Everyone brought those experiences back to the studio, and she says you can hear it all on Paper Airplane.

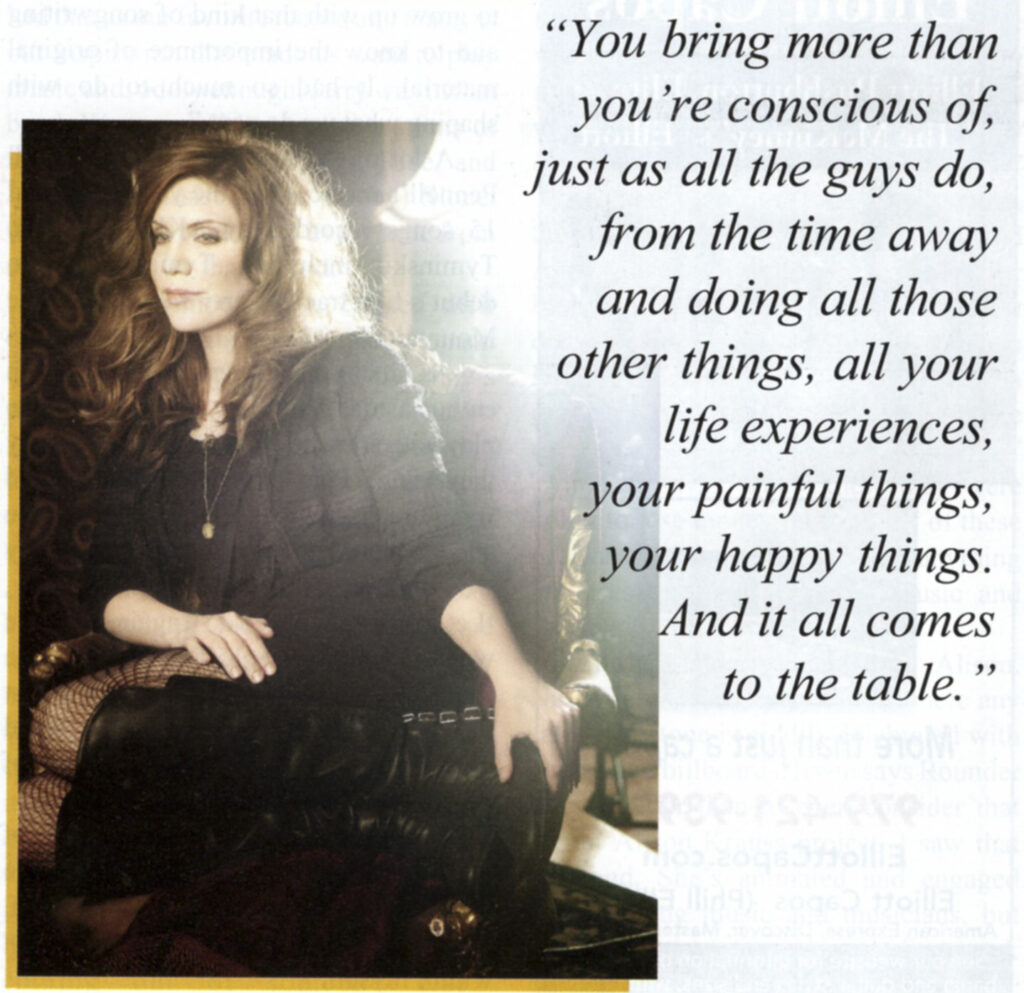

“You bring more than you’re conscious of, just as all the guys do, from the time away and doing all those other things, all your life experiences, your painful things, your happy things. And it all comes to the table.”

Her recorded autobiography began when she was barely a teenager. It’s easy to forget, as she continues breaking new ground as the most successful bluegrass artist ever—topping mainstream country charts in her new album’s first week of release; chatting with the ladies of The View; hitting the late-night talk circuit; appearing at the White House; singing with pop, rock, and country superstars, including her famous 2004 Academy Awards appearance wearing borrowed $2 million diamond-encrusted shoes, duets with Sting and Elvis Costello—but Alison Krauss got her start as a Midwestern pre-teen fiddle prodigy.

Champaign Dreams

She grew up in the college town of Champaign, home to the University of Illinois. Her dad, Fred Krauss, was a German immigrant who came to the States in 1952 and taught his native language. Her mom, Louise, of German and Italian descent, is the daughter of artists. Alison got her tireless work ethic from her dad and her equally resilient artistic streak from her mom. “In my father’s family, it was nothing but academics, and in my mother’s family, it was art. So they wanted to make sure they gave us those opportunities.”

Music was just one activity Mrs. Krauss got her kids Alison and Viktor into. “I thought everybody took all these things we took. She exposed us to visual arts and we did dance and some sports, which was a lost cause,” Alison says with a laugh. “Not only were we exposed to all this music, but my mother would take me to the University to the performing arts center and we would sit in on dress rehearsals and we’d see Kabuki theater and all kinds of stuff. And one of the things she wanted us to do was take an instrument for five years.”

Alison started violin at five. By seven, her mom was driving her to contests. “She’d heard about fiddle contests in Champaign at the County Fair. And we had Richard Greene’s album, Duets, and I learned ‘Little Rabbit,’ and we also got this book. Old Time Fiddling.”

It didn’t take long for the cute green-eyed blonde kid with the hot fiddle to get noticed. One of her dad’s ex-students, songwriter/bassist John Pennell, remembers seeing her in the local paper. “My mom showed me the article,” John recalls, “And said, ‘I think that’s Fred Krauss’s daughter.’ She knew that he was my German teacher back in high school.” At the time, Pennell was playing with another Champaign fiddle whiz, Andrea Zonn, a couple years Alison’s senior and today one of Nashville’s most in-demand session fiddlers and backup singers. Heartland was an eclectic classical/jazz/ bluegrass group that included Andrea’s dad, music professor Paul Zonn. When Pennell left to start a more traditional bluegrass band, he needed another fiddler. A drummer friend suggested one of his students and gave Pennell Alison’s phone number.

“So I called her,” says Pennell, “And Alison goes, ‘Well, my brother plays bass, and I sing, too. Can we sing?’ And I said, ‘Oh, that’s nice, but Nelson and I can cover the singing pretty well.’ I wasn’t expecting much. I certainly wasn’t expecting anybody like…her.”

Despite misgivings about her age, Pennell (on guitar), mandolinist Nelson Mandrell, and banjo player John Gantz set up an audition. “So she came over and she was 12, and her fiddle bridge was kinda falling off and her mom was fixing it. She seemed a bit nervous and we played, and she played pretty good and Vik played the bass. So we got done and then she said, ‘Do you want to hear me sing?’ And we said, ‘Well…sure. What do you want to sing?’ And she said, ‘Blue Kentucky Girl.’ So I kicked it off and she started singing, and I mean it was just like, ‘Holy…! You gotta be kidding!’ Not only were we getting a fiddle player, but we were getting a lead singer that was obviously destined for stardom.”

The study habits Alison had gotten from her dad were applied to bluegrass, with Pennell and Mandrell her eager teachers. “When she first started playing with us, she didn’t do any improvisation,” says Pennell. “She couldn’t sing harmony. Of course, with that ear, it didn’t take her long. She really started learning. She’d listen to Bobby Hicks and Ricky Skaggs. She listened to Ricky a lot. She was listening to all the country stuff on CMT and she was into New Grass Revival; she listened a lot to Sam (Bush) and John Cowan. And she also is a big fan of Journey and Foreigner, but she never ever let us know that.”

John soon introduced her to her new favorite artist. “She was going to these fiddle contests, and she would get these guys to play backup and this one guy was her favorite. I mentioned Tony Rice and she had never heard of him.’ I said, ‘Here, I’m just gonna put on “Your Love Is Like A Flower.” Listen to his rhythm playing and his voice, and the lead break will speak for itself. And I’ll come back in five minutes.’ That’s all it took. That’s all we listened to for five years was Tony Rice.” Alison remembers Mandrell playing her Ralph Stanley’s Clinch Mountain Gospel, but Pennell stuck to the gospel according to Tony, with a little Skaggs—and Beatles—thrown in. “Pennell made me tapes,” she remembers. “The Bluegrass Album Band, J.D. Crowe & the New South, Boone Creek.”

As inspiring as the music was, she says the older men’s love of that music was even more inspiring. “John and Nelson both were just so passionate about music, insanely passionate. And John is still the same way. He’s so passionate about what he likes and it was really great for me to hang out with him like that. And he would be writing songs, and it was great to grow up with that kind of songwriting and to know the importance of original material. It had so much to do with shaping what we do now.”

A lot of “what they do now” is still Pennell’s music. Over the years, he’s had 15 songs recorded by AKUS and Dan Tyminski, including Tyminski’s solo debut’s title track “Carry Me Across The Mountain.”

As much as she learned, she repaid in enthusiasm. “The thing about getting to play with somebody like that is the energy they bring,” Pennell remembers. “She had sooo much energy. We would rehearse and we would get those songs where they would be perfect, and she would say, ‘Let’s do it again, let’s do it again.’ And we would do them 10 or 15 times, just for the sheer pleasure of doing it. We were past the point of trying to sing it right. We’d already got that. It was just for the joy of it.”

That drive is still very much a part of her. “You want to do well,” she says. “I’ve always had a competition within myself. Not so competitive with other people, but within myself.”

Alison admits her early passion for bluegrass could get obsessive. “I listened to (Tony Rice’s album) Cold On The Shoulder eleven hours straight one time, driving to Arkansas. And my dad let me play it the whole time. He didn’t say anything. I still can’t believe it.”

AKUS Takes Off

Her parents’ support paid off. At 13, Alison was offered a record deal with Rounder Records, the label that had released all those Tony Rice albums, those Bluegrass Album Band records, Boone Creek’s debut, that Richard Greene album with “Little Rabbit,” and the Sgt. Pepper’s of modern bluegrass, J.D. Crowe & The New South, Rounder 0044 with Rice, Skaggs, and Jerry Douglas.

Rounder co-founder Ken Irwin first heard her on a demo by Classified Grass, the other Champaign band she played with when not working with Pennell’s group. Silver Rail (after they discovered another band with that name, they became Union Station).

“My understanding was she had a schedule on the refrigerator, and whoever called up first, she would play with,” Irwin recalls. “The tape I got wasn’t an Alison demo, it was a band demo, and she was the harmony singer and the fiddle player. And it wasn’t until the fourth song that she sang lead, and it was a gospel tune. That’s what I was taken by.”

Irwin was interested in her as a solo artist and called the Krauss home to talk business. “To my surprise, I got to speak to her and she was very mature and handled it very well. And I asked to hear more material and got some, I think, by the end of the week. And at that point, it was mostly Pennell songs and it was mostly with Union Station. Apparently, what had happened, her parents, with the positive feedback, went in and did new recordings. That was pretty incredible in terms of family support.”

Once she was signed, Irwin took her (and her parents) to Nashville to find a producer for her debut. That’s when she started meeting the names she’d been reading on the backs of all those albums, including Bela Fleck, Sam Bush, and future AKUS member Jerry Douglas.

“Ken Irwin brought her over to Bela’s house and Bela and Sam and I sat there and Alison sang for us, and mostly just wanted to play the fiddle,” remembers Douglas. “She wasn’t that interested in being a singer at that point. And we were all like, ‘You should be a singer!’ I think all three of us knew exactly right then that something huge was gonna happen with her.”

She had the talent, but needed seasoning. In 1989, she toured with the Tony Rice Unit and, in the early ‘90s, turned heads with Masters Of The Folk Violin, a prestigious tour produced by the National Council For The Traditional Arts featuring bluegrass master Kenny Baker with Josh Graves, Cajun fiddler Michael Doucet, and jazz great Claude Williams.

Things were moving quickly for Alison and her band, too quickly for Pennell, who left in August 1989, while Union Station was still based in Champaign. “I was just wore out,” says John. “We were driving in this van and we were driving long hours. I was 39, 40 years old and couldn’t keep up with this 17-year-old-kid. I would get home and it would take me a whole week just to get enough energy to go back out.”

By the time Pennell left, Alison had recorded two albums, her Rounder solo debut Too Late To Cry (1987) and AKUS’ debut Two Highways (1989). Pennell remains one of Nashville’s most respected songwriters, in the past year landing cuts with the Charlie Sizemore band, with whom he occasionally plays bass, as well as Sierra Hull and a recent duet by Junior Sisk and Rhonda Vincent (“The Sound Of Your Name”). Non-bluegrassers like Alan Jackson and the late Eva Cassidy also recorded his songs.

In those early years. Union Station’s lineup was in flux. Viktor Krauss briefly replaced Pennell and Alison Brown played banjo. In 1990, bassist Barry Bales, guitarist Tim Stafford, and mandolinist Adam Steffey joined from the band Dusty Miller. Ron Block took over banjo in 1991 and AKUS solidified in 1992, when Dan Tyminski left Lonesome River Band, switching from mandolin to guitar to replace Stafford. That lineup’s commercial breakthrough came in 1995 with the two-million-selling Now That I’ve Found You: A Collection. But Steffey left in 1998, and the band was at a crossroads when they asked Jerry Douglas to play some shows.

“When I first joined the band I didn’t know how long it was gonna be,” says Douglas. “She asked me to go out and do some dates while they made up their mind if they wanted to be a band anymore. And about two weeks into it, they asked me if I would just stay.” He asked for billing since he was putting a busy solo career on hold. “I didn’t want to be anonymous for the summer,” he explains. They became Alison Krauss + Union Station featuring Jerry Douglas, though the acronym remained the less cumbersome AKUS. Having played on so many of his new bandmates’ favorite records, Douglas jokes that he suffered deja vu as they rummaged through his musical resume.

“Oh man, for the first year, they would kick off ‘Old Home Place’ and I would just roll my eyes,” he says with a laugh. “I would say, ‘I was really hoping we would do something different.’ And we have. But every gig, we do ‘Cold On The Shoulder,’ ‘Rock Salt And Nails’; something comes up during every soundcheck. And I say, ‘Oh my god, here we go again.’”

For Douglas, bluegrass began with Flatt & Scruggs and his idol, Uncle Josh Graves, but for the rest of AKUS, the wellspring remains Rounder 0044. “That’s still what we kind of measure everything against when it comes to that type of bluegrass music,” says Tyminski. “We all had that as our favorite record and that was our inspiration that made us want to play music and, oddly enough, Jerry was in that band. We were all just enormous fans of the New South with Skaggs, Rice, and Jerry and (bassist/fiddler Bobby) Slone. Growing up. I could play every note from every player on that record.”

AKUS members have created their own groundbreaking recordings. Tyminski made history singing George Clooney’s part for “I Am A Man Of Constant Sorrow,” from the eight-million-selling O Brother, Where Art Thou? soundtrack, celebrating its tenth anniversary with an expanded commemorative CD.

“When I look back, it’s just amazing how something like that could come together,” says Tyminski. “My manager mentioned that I might be a candidate to sing Clooney’s part. I said. ‘Really?’ I couldn’t see it at first. But as it turned out, it ended up being so believable, I just could not count the number of people who thought it was Clooney singing that. He just did such a great job at how he did the lip sync. But it’s weird to hear your voice coming out of someone else.”

It’s become Tyminski’s “Rocky Top.” He still sings it every night. “It’s amazing the longevity of that. Whenever we play it, within the first three or four notes, it just immediately gets a response. People are waiting for it. It’s very strange, but very fun.”

Tight-Knit Crew

Tyminski knows that O Brother could have kick-started a solo career, and with any other band, he might have given it a shot. “But there’s just nothing that I could do that could ever mean as much to me as this combination of people. Listening to the music. I’m such a fan of everybody in this band. But outside of the music, just from who we are as people, I just have such a high level of respect for these guys. I just couldn’t imagine being anywhere else.”

He had major solo success during the AKUS hiatus with Wheels by the Dan Tyminski Band (Bales and Steffey, Ron Stewart, Justin Moses, and guests Vince Gill, Sharon and Cheryl White, and Ron Block). Wheels won Tyminski the IBMA’s 2009 album and male vocalist honors. He’s a 2011 male vocalist nominee, one of the band’s seven IBMA nominations, including instrumental nods for Bales, Block, and Douglas and female vocalist for Alison, who’s also part of song and recorded event nominations with Dale Ann Bradley and Steve Gulley on Louisa Branscomb’s “I’ll Take Love.”

Naturally, Wheels was on Rounder, the label that remains home to Alison and AKUS, as much as for what it does for bluegrass and traditional music as what it does for them. “You have to have such a large amount of respect for anyone who gets into the record business for the reasons that Rounder got into it,” Tyminski says. “They knew they were going to lose money on so many of these projects, but it was never about anything but preserving that type of music and sharing it with the world.”

And Rounder understands Alison. Nashville is an industry town, where any sales milestone is giddily celebrated with parties and billboards. Irwin says Rounder knows better than to even consider that for an Alison Krauss project. I saw that firsthand. She’s animated and engaged when talking music and musicians, but mention her unprecedented first-week number one chart position for Paper Airplane, and she shrugs it off with visible irritation. “That was great. We were thrilled,” she replies in a robotic monotone. When I offer that her first-week sales of 83,000 were more than four times what most successful bluegrass albums can expect in total, she gets angry, her voice rising. “That’s a shame.”

Maybe it’s that German Midwestern upbringing, but for Alison Krauss, the reward, the joy, is in the work. “It’s remained about the music. It’s remained about her friends,” says Irwin. “She’s an extremely loyal person. She just loves bluegrass and loves the people. She keeps in touch with Larry Sparks on a regular basis as a friend. She loves going to see other acts.”

She and her band have inspired generations of musicians, especially young women. No one personifies that better than Sierra Hull. Now eighteen, the singer/mandolinist became a fan at nine when her dad gave her Forget About It. “To this day, it’s one of my all-time favorite albums. I remember just falling in love with her music, and Adam Steffey was just such a big influence on me. I would cut out pictures of them and stick them in my notebook at school. I’d draw pictures of me possibly one day playing with them.” At 11, Sierra got her wish, performing with AKUS on the Grand Ole Opry at Alison’s invitation. “I always imagined her being a sweet, wonderful lady,” says Hull. “It’s just really great to meet a hero who lives up to the person you imagine them being.”

Even as Alison leads her band and makes tough business decisions like hiring new management (Borman Entertainment) and a new booking agency (CAA), she retains that same open-hearted sense of wonder she had when she first heard bluegrass coming out of John Pennell’s car stereo on the streets of Champaign.

“I’ve always loved the message that bluegrass has the purity of it. It’s always, ‘There’s nothing more beautiful than the girl next door. There’s nothing more wonderful than Mom and Dad. There’s nothing more passionate than this man running away with my beautiful girl next door.’” She shivers, then laughs, displaying the goosebumps on her arm. “Chills,” she says. “I daydreamed about that life when I first listened to the stuff, riding around with John. That message is what we carry, even though we might have more contemporary lyrics. You can’t explain it. It’s the stuff that makes you daydream and you don’t know why.”

One of her more playful daydreams casts Tyminski in the recurring role of a Bluegrass Job, railing against the indignities of God and man, as in his O Brother hit or Paper Airplane’s “Dustbowl Children” and “Bonita And Bill Butler.” “When I think of Dan, in my mind, he’s that guy yelling at the sky, ‘Why isn’t there any rain!?’ Or he’s on the ship in the storm. He’s the lone guy who screams into the sky. He’s the farmer, he’s the prisoner, he’s the soldier. This time, we added sailor. We’re just happy he agrees to sing them. He always asks, ‘OK. what am I this time?’”

Bales also takes a new role on Paper Airplane—songwriter. He penned “Miles To Go” with former Steel Driver Chris Stapleton and has been co-writing with New Found Road’s Josh Miller. During the AKUS hiatus, he played in the Tyminski band, co-produced Sierra Hull’s 2011 CD Daybreak and subbed for Dennis Crouch in Nashville’s premier western swing band, the Time Jumpers. He also traded the Nashville scene for his native East Tennessee, moving back to work his family’s 165-acre farm, enjoying what he calls “diesel therapy.” But he’s glad to be back on the AKUS bus. “When we’re back together and on the road and have everything clicking and tight, there’s no feeling in the world like playing with this group of people,” Bales says.

Ron Block agrees. “I hadn’t played with Dan for a while. And when we were doing rehearsals, before we started, Dan and I were standing in the corner and we played some standard like ‘Toy Heart,’ and when we finished. I just thought, ‘My banjo goes with that guitar.’ For me, the way Dan plays guitar while I’m playing banjo is just amazing. He knows my playing so well, he knows how to interact and I know how to interact with him.” Block released a solo album. Door Way, in 2007, but with two kids getting close to their teen years, much of his AKUS break was spent enjoying his home and family south of Nashville. “I kind of was on hiatus myself a lot in these past four years,” he says. “And I’ve learned a lot, but I wasn’t out there a whole lot except for doing things like with certain people like Sierra Hull (Ron coproduced her 2008 debut, Secrets, and has filled in on banjo). But those last four years, for me has been a time to reassess what’s important and really think through a lot of things. I’ve really not written a lot of songs, but though it’s been a kind of a dry time, it’s been a good family time and a good learning time for me spiritually. So, I feel the next few years are going to be a good productive time. We go through phases like that, but this summer we’re rolling and we’re going, and it sure is fun being back out.”

Flight Delays

Alison says the break between studio albums wasn’t meant to be seven years. “We weren’t supposed to wait that long. But I had to finish touring with Robert, and then I kept getting sick, and getting migraines, and I couldn’t concentrate. So we’d take a break and then we had to get everybody back together, which was near impossible.”

The delay caused rumors in the bluegrass world. Some said the first version of Paper Airplane was scrapped and the entire album re-recorded. Not so, says Douglas. “We only recorded it once, but we just recorded a lot more songs than we’ve ever recorded to get the ones, you know? We’d think ‘This is great, this is great, this must be it.’ And then we’d record it and it was just like, ‘This isn’t good enough. We’re going to keep going until we get it all good enough.’ And you know, for a lot of people it might be good enough. But for us, we have a really high bar.”

He says Alison was under a lot of pressure. “I think she was having these migraines because she was so worried: it had to be a really important record. It was a comeback record, the first thing after the Robert thing. Rounder had [been] sold to Concord: we were changing managers. There was a lot going on and I think that triggered the migraines and I think it triggered the soul searching for the record. She couldn’t be sure. Her head hurt so bad, she couldn’t really commit to anything. She’d do it and it would be great, but at the end of the day she wasn’t sure what she had done. It was really physically demanding, way beyond. We all knew it and I think it permeated the sessions. We didn’t know if it was gonna work.”

That hard work paid off. The album has several versions, including expanded editions for bricks-and-mortar retailers like Wal-Mart and Target that demand unique packages—another new industry wrinkle. The 11-song standard version combines originals by frequent AKUS contributors like Robert Lee Castleman’s title song, her brother Viktor’s “Lie Awake” and Sidney Cox’s “Bonita And Bill Butler,” with songs by Richard Thompson (“Dimming Of The Day”), Peter Rowan (“Dust Bowl Children”) and Jackson Browne’s closer, “My Opening Farewell.” There’s thumping bluegrass, ethereal ballads and, soaring through it all, that amazing crystalline voice, like Heaven’s saddest angel. It was a struggle getting through it, but everyone, Alison included, says it was worth it.

“I feel like it’s a new start. I don’t remember ever having as much fun playing as I have since we started this go-round,” she says. “My favorite times were also back riding in the van and sleeping on the floor. I loved that. But everybody’s personality and everybody’s playing and the commitment to the band makes this a really special time. To get that amount of time of playing together, it starts to move; the whole thing moves around a little bit. And that’s what I’ve noticed with the band, and that’s exciting.”

The band has seen changes in her as well. “I’ve never heard her laugh so much,” says Douglas, who’s known her longest. “She was 14 when she was in that living room that day. And I’ve never seen her so happy, and she’s grown into it. There was all that angst we used to go through recording, like recording an intro for two days. And she’s let that go. Records are snapshots of where you are at that point in your career, in your musical life And I think you slowly realize that over time. But it takes you a while to agonize over those last notes. When you’re onstage and you do something that you didn’t want to do, that will stick with you for a certain amount of bars. You slowly get over that as you get older. You don’t pay as much attention to what just happened as you’re looking forward to what’s going to happen next. And you should be able to use that in everything you do in life. We’re all getting better at what we do.”

Alison, who turned forty on July 23 (on tour and onstage with AKUS) says she’s ready for what’s next. But she’s also enjoying where she is right now. “I’ve always thought that what I would do in my later years would be my favorite thing. When I’m not kept up by something that is so moving to me. then it’s done. Then I’ll stop. But it’s more exciting to me now than ever.”

Larry Nager is a Nashville-based writer, musician, and filmmaker. His documentary. Bill Monroe:Father Of Bluegrass Music, is available on DVD.