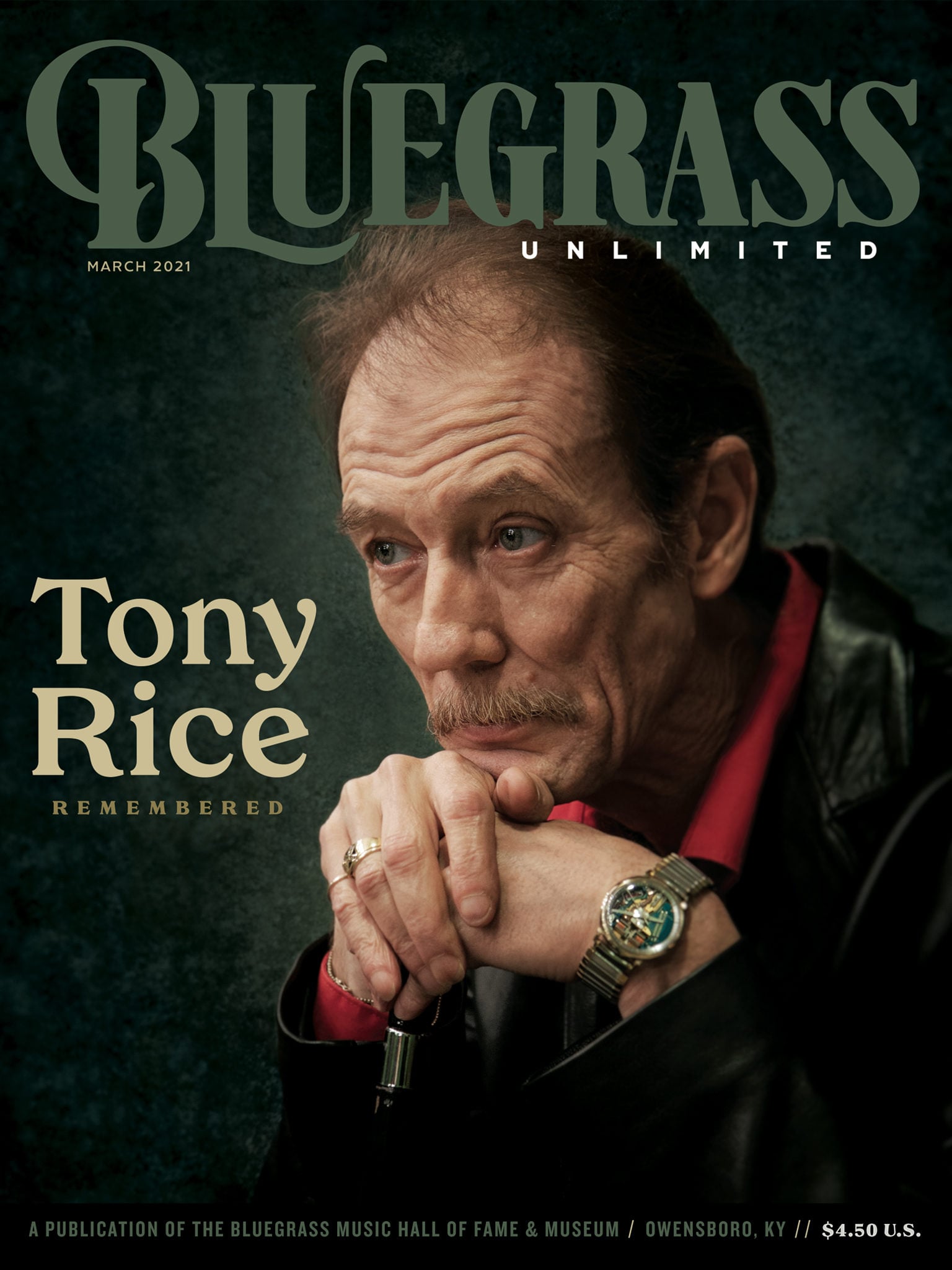

A Means to an End: The Richard Hoover/Tony Rice Quest for the Ideal Guitar

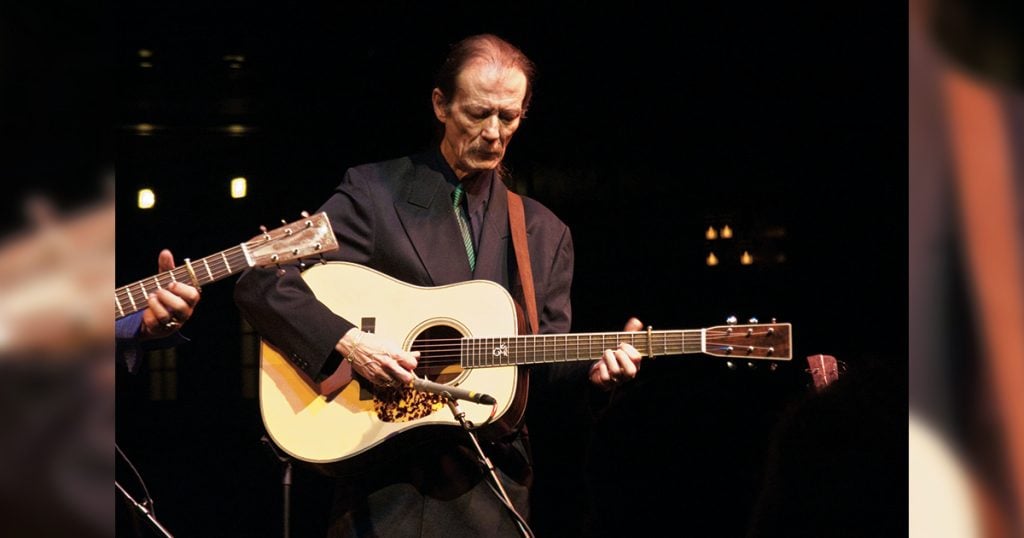

By the time it got into Tony Rice’s hands, the iconic 1935 Martin D-28 had seen more than its fair share of wear. Known as “The Antique” or “58957”, the guitar rested under Joe Miller’s bed for nine years before Tony acquired it in 1975 and soon brought it to Randy Wood for a neck reset.

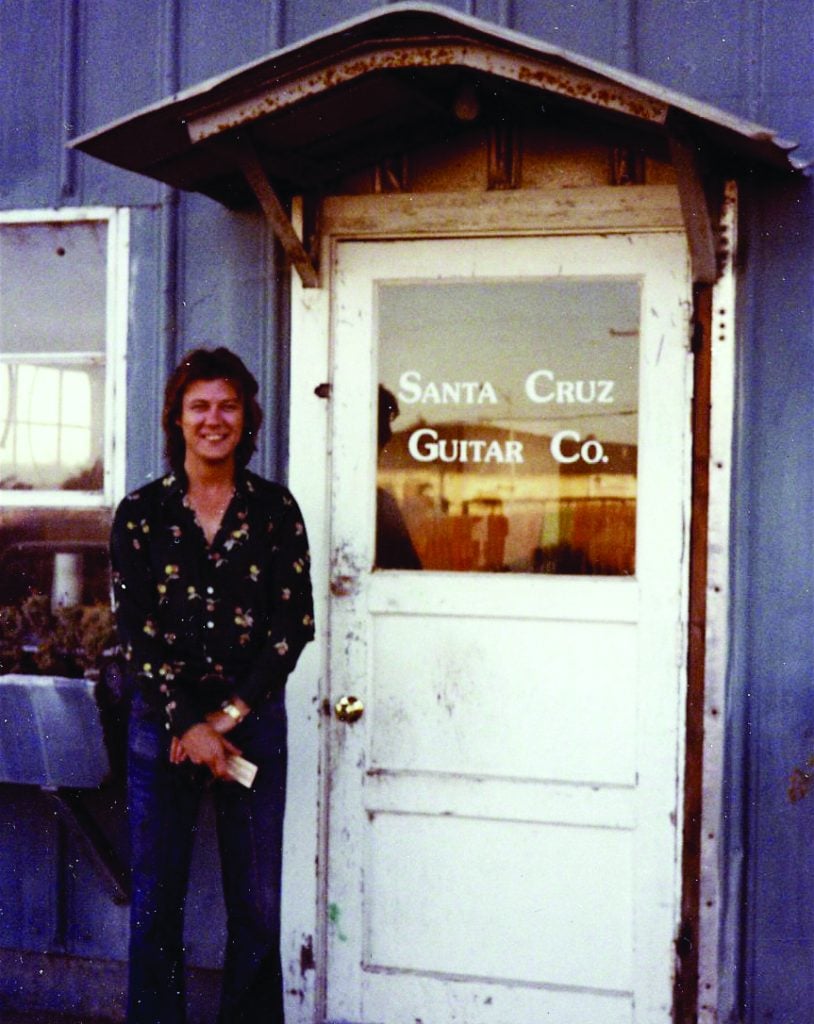

When Tony was working in California with the David Grisman Quintet, Darol Anger introduced Tony to Richard Hoover, who had just opened the Santa Cruz Guitar Company. Hoover was only one in a long series of notable luthiers (including Mike Longworth, Bob Willcutt, Hideo Kamimoto, Harry Sparks, and finally Snuffy Smith) to tweak 58957. But it was Hoover to whom Tony turned when he decided to get a version of 58957 that he could take on the road without worry.

Over the next 37 years, the Hoover-Rice collaboration resulted in more than a dozen variations of the dreadnought guitar and gave birth to the Santa Cruz Guitar Company’s “Tony Rice” models.

Hoover recalls, “When we started out, Tony was very clear: he wanted some differences in sound, but he also wanted it in a really familiar package. He had bonded to his guitar [58957], so he wanted it to look like his old instrument in many ways, but that’s where the similarity ended. Tony wanted an EQ that provided more midrange and treble, enabling him to accentuate lead work without sacrificing the tone of the old guitar.”

Part of that path to enhanced midrange and treble was already present as a hallmark of 58957 because of the whittling of a previous owner. “It’s just simple, well-established physics,” Hoover explains. “The larger the sound hole, the higher the fundamental frequency of the airspace of the body, which enhances the high ends. But we also shaped the braces differently, which is another way to affect the EQ of a guitar.” Another part of the puzzle—clarity of tone—was the choice of wood.

The Santa Cruz Guitar Company was equal to the task. From the founding of the shop, states Hoover, “That was our specialty: building instruments that focused on sound needs and not just on looks.” Of course, the look of the guitar was already well-defined.

“So for the first two or three guitars,” Hoover recalls, “we were dialing that in. When I first talked with Tony—keep in mind that I’m only 25 at this time—we tried to make a guitar for Tony that would also serve the greater guitar market. I thought I knew better than him, so of course the first one was not right. For the second guitar we dialed in the EQ and used a cedar top, which immediately produced an older, warmer tone: it sounded like an older guitar. And Tony used that guitar on some of his recordings for a few years. But we could not leave well enough alone, so we continued to ‘refine’ with subsequent guitars.”

Richard explains: “There were a number of reasons for subsequent guitars. It’s not that Tony got tired of or outgrew the guitars, but personal situations required changes and the incorporation of new ideas. Some were functional, like fingerboard width, string spacing, scale length, but by the sixth guitar – somewhere in the late 90s – we were addressing manual facility. Doc Watson plays from the elbow and Dan Crary plays from the wrist; Tony played from his fingers. Most of us would not survive that for long.”

Tony’s unique picking style (precise repetitive micro-motions of thumb and fingers) began to require solutions that minimized stress. “After a point Tony realized that if he was going to continue to play he needed to put forth less effort to get the sound he wanted or he was going to injure himself. One of our solutions was a shorter string length: when you tune (a shorter) string to pitch, it actually requires less tension to get to pitch and requires less effort to press the strings down. So, we went down to a 25.25-inch scale length. We experimented with implementing several other tension-lessening solutions. Tony’s herringbone had been modified so that the nut width was about 1 & 5/8 inches, where 1 & 11/16 inches was pretty much the standard in those days. Tony was used to that nut width. Providing more space between the strings also relieves stress in the fretting hand. So, with subsequent guitar revisions we increased the nut width and increased the spacing at the bridge for his picking hand.”

Once Tony’s fans saw him playing a Santa Cruz guitar, the requests to purchase “the same guitar Tony plays” began to build. From its onset, the Santa Cruz Guitar Company has always been a custom guitar shop, focused on working with players who have a good idea of what sound they want, the desired shape of the instrument, an appreciation of the time required for production, and are willing to pay for an instrument that helps them tell their musical story.

Richard recalls: “From the beginning of our association, Tony encouraged me to build a guitar for his fans. Since most folks can’t go out and buy a prewar D-28 (which was the sound that we were producing with our guitars), Tony saw that the opportunity to buy that guitar was a service to his fans. So, we agreed that we would build the things he wanted into a production instrument, the Tony Rice model. And after the first few guitars we froze the specifications for the Tony Rice model. As we progressed with modifications to accommodate Tony, we decided not to confuse folks by changing the model all the time. Those Tony-specific modifications did not make the guitar better. We also discussed that as we grew as luthiers we would improve the guitar, providing better truss rods or enhancing stability and other things we would normally do. And the Tony Rice model we make today is very true to that arrangement: it provides the sound Tony wanted but keeps pace with improvements in the building process. But we did have to introduce the Tony Rice Professional, for those folks who wanted ‘one exactly like the one you made for Tony.’ So that model has Brazilian rosewood, nice old spruce, the enlarged sound hole, the shaped braces, the advanced X-bracing, and other features that Tony specified. And if someone wants special inlays or other modifications, that guitar is no longer a Tony Rice model, but becomes a custom Dreadnought.”

But Richard is quick to stress that his decades-long relationship with possibly the premier guitarist of our age was not focused on guitars. “We were introduced by a mutual friend, and it started out with guitars, but over the years our conversation focused on guitars about eight percent of the time, if even that. Our relationship was based on common challenges and successes and disasters in life, stuff we all go through. It was more a mutual journey of discovery though relationship problems, romances, spirituality, and all the other stuff that’s really important in our lives. The message is this: if you love someone, tell them now. Don’t wait.”

For further information on The Santa Cruz Guitar Company and its line of guitars (including the Tony Rice models), see santacruzguitar.com.