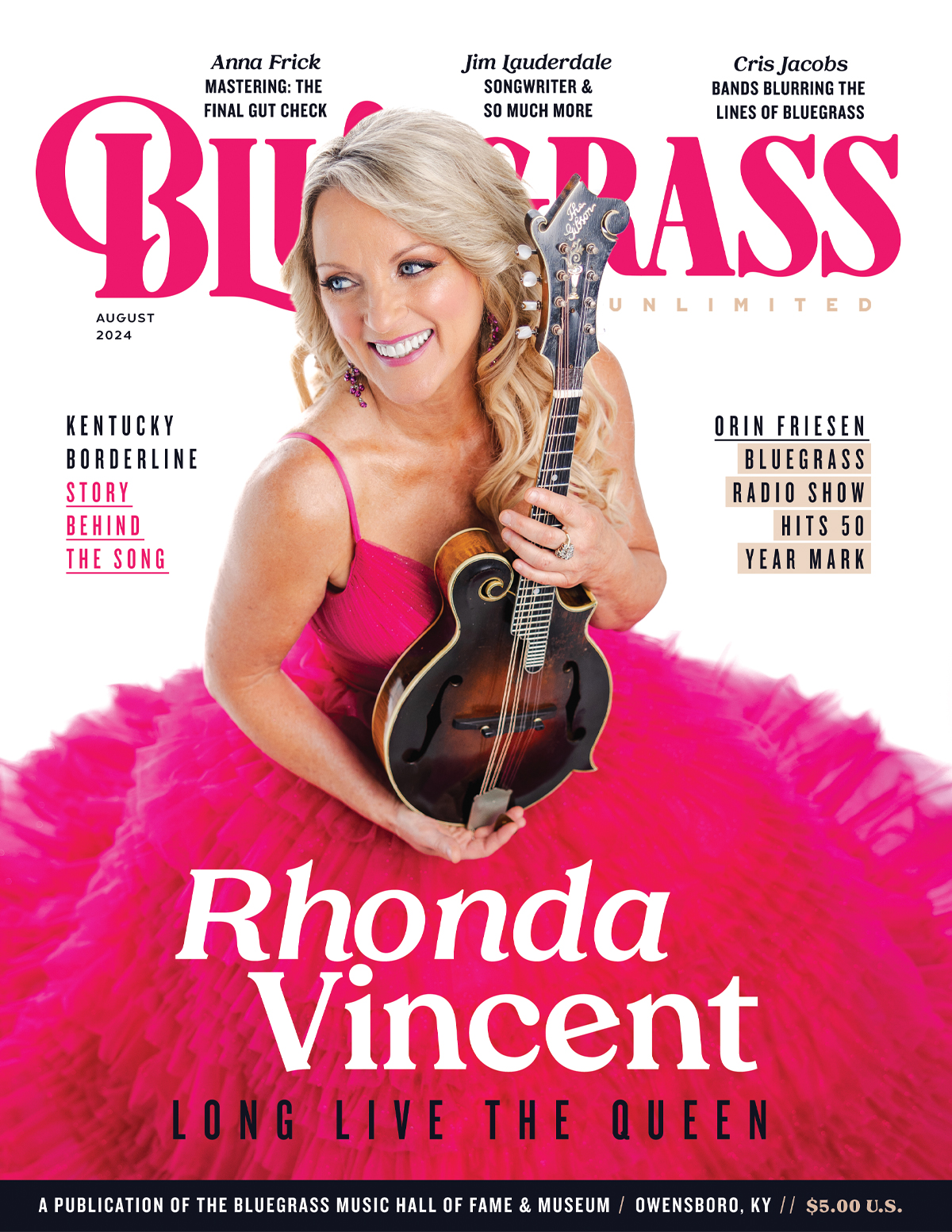

A Broadcast Legend

Bluegrass Radio Show Hits the 50 Year Mark

While various areas of the Appalachian region are considered the main hotbed for bluegrass music, there are other faraway parts of the U.S. where the music is appreciated and thrives. One excellent example of this is Orin Friesen’s bluegrass radio show, which has been broadcast from Kansas for an amazing 50 years.

Friesen’s radio program spread the gospel of bluegrass music throughout the western part of the Heartland region, which buttresses the Rocky Mountain Front Range on its western side. That was especially important back when a radio signal was confined to its broadcast range, in a time before other forms of digital inventions enabled a show to be streamed around the world. But, above and beyond the change in technology, to consistently broadcast music for over 50 years is an incredible achievement, no matter what genre of music you are spinning.

In 2012, the International Bluegrass Music Association (IBMA) gave Friesen a Distinguished Achievement Award for sharing bluegrass music over the airwaves with his long-running radio program. Now, Friesen’s Bluegrass From The Rockin’ Banjo Ranch Radio Show has passed the half century mark and as the old adage says, “Time flies when you’re having fun.”

At the core of the years that Friesen has now spent on the airwaves are the mystical times of his youth when a fascination and a love for the magic of radio was sparked inside of him. In those days, seven decades ago, here was this box powered by either an electrical cord or a battery that took invisible waves broadcast from a radio station many miles away and translated them into the sounds of the human voice and music, all using an antenna and a speaker.

This was an era that existed long before the advent of affordable and easily accessed satellite radio, internet broadcasts or smartphone streams. It was an era when a transistor radio could pick up a distant radio station broadcasting live from a town hundreds if not thousands of miles away in the U.S., or on a clear night, was beaming in from Canada or even Cuba.

Long before bluegrass music entered Friesen’s life while in college, his life on the farm as a child fortunately featured a radio in the house. “On Saturday nights, we would take baths in a washtub on the kitchen floor and my Dad would have the radio on and we would listen to the CBS portion of the Grand Ole Opry that went out nationally, which was brought to you by the Prince Albert Tobacco company, and that was one of my earliest memories of radio,” said Friesen. “I was born in 1946, so this would probably have happened in the early 1950s when I was a kid living in York, Nebraska, located 50 miles west of Lincoln, which was the capital of the state. We lived on a farm.”

Life on the farm suited Friesen just fine, especially after he found out that he was better at handling certain tasks and not others. “I aways wanted to be a cowboy, so I was the one in charge of the horses and the cattle,” said Friesen. “My brothers, on the other hand, gravitated more towards driving the tractor. I like driving a tractor now, but I didn’t back then, because my Dad was very picky and he had to have exactly-straight rows in the field. We had one of the best-looking farms in our area. So, if I got distracted by thinking about music or radio or something like that, he would get upset if the rows weren’t perfectly straight. But, I knew I could handle the animals, and that is what I liked to do.”

Friesen’s family had an old Crosley radio in their house, which are now collector’s items and sought-after antiques after the company went out of business in 1956. “I think we had an old wooden radio, but I also remember the old Crosley radio that we moved out to the barn because it was made with that Bakelite coating on it, I think,” said Friesen. “But, I remember listening to that radio in the barn while I was milking the cows. I especially enjoyed being out there on Sunday nights because that was when Gene Autry’s Melody Ranch radio show was on. So, I would always try to plan to milk the cows while that show was airing, which ended in 1956. At that time, the radio stations were not playing just rock & roll or even country as they played a little bit of everything. But, that is how I got to like all kinds of music.”

During his years on the farm, Friesen also acquired a shortwave radio at an early age and eventually he got a regular radio of his own as well. Both of these contraptions spurred his scientific curiosity and imagination.

“One day, I found an old motor in our hedgerow and I took it apart and unwound all of that copper wire and made a long wire antenna out of it,” said Friesen. “I strung that wire from my bedroom, which was upstairs in our two-story farmhouse, all of the way to our windmill. When I could hook up my radio to this big and long antenna, I could hear practically every radio station around the country. Then, I would switch over to the shortwave radio and listen to stations broadcast from around the world.”

Once Friesen was hooked on all things radio, he built his own broadcast transmitter, using a Heath kit that had a little vacuum tube in it. “My Dad would get in his truck and go out into the field and listen to me do a radio show, because we lived out in the country and nobody else could pick up the signal because we were too far from anybody’s house,” said Friesen. “So, my Dad would drive out into the field in his old Ford Pickup truck and he would turn my broadcast on so I had an audience of one person. I couldn’t play any records or anything like that, so I guess I just talked over the air.”

Imagine a father driving his truck out into a farm field in Nebraska in the 1950s and then moving the dial on his truck radio until he heard the sound of his son’s voice coming out of the speakers, and doing it so his son had at least one person on the planet hearing his broadcast emanating from the second floor bedroom of an old farmhouse. That may have seemed like a simple thing to do at the time, but looking back, the imagery is fascinating and captures a moment in history long gone now.

As a teenager, like most people his age in the late 1950s, Top 40 AM radio was a passion that enabled kids to keep up with all of the latest music hits and sounds. Friesen had favorite stations that he would tune into from time to time, from KOMA in Oklahoma City to WLS in Chicago and other broadcasters depending on when the sun went down.

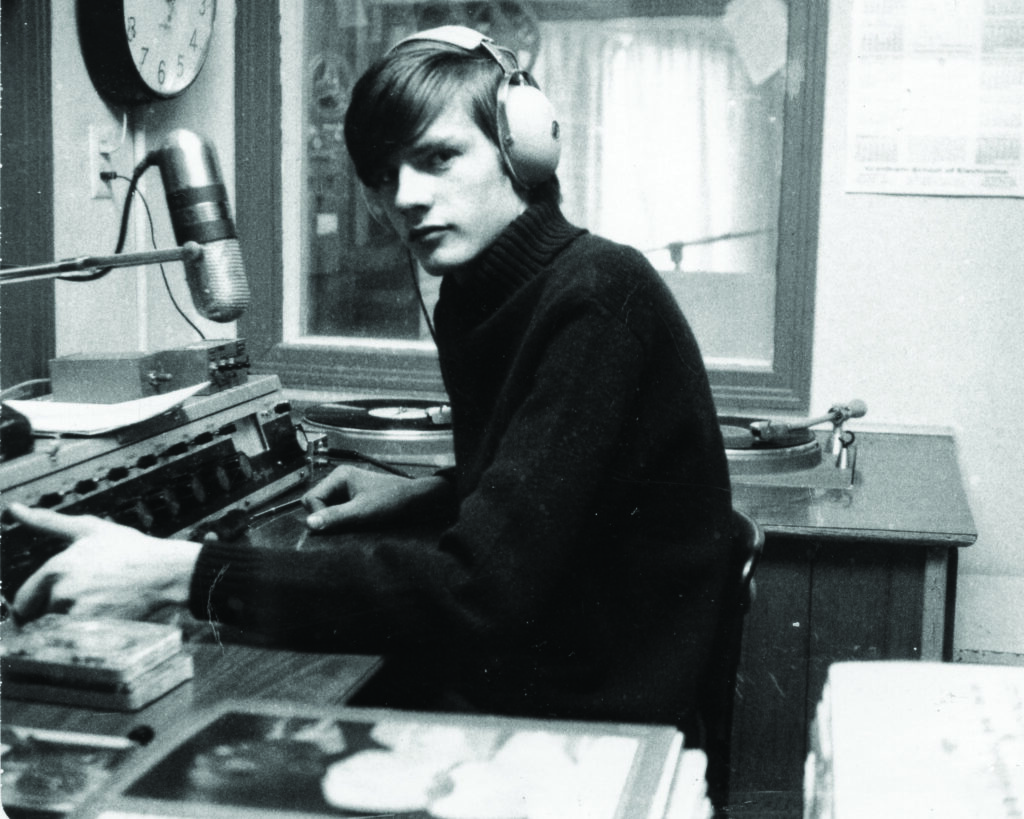

After high school, Friesen found himself enrolled in college and when the opportunity arose, he pursued the chance to be a DJ on the college radio station. It was an interesting time in music as rock & roll had exploded onto the scene, and the big Folk Boom of 1960 to 1963 was in full swing as well.

“We were a college station and the other stations in town were playing rock & roll music and we had to play something different,” said Friesen. “At that time, college stations did what is called block programming, as in playing classical music for an hour followed by jazz, and then I did my hour of folk music. Sometimes, I would also sit in on the classical music show, and a time or two, I sat in on the jazz show as well, even though I didn’t know anything about it.”

Eventually, the focus of Friesen’s show switched from folk music to bluegrass.

“When I started my first radio show in college, I didn’t know what to do at first, but then I had a roommate that was really into folk music,” said Friesen. “In the early 1960s, the Kingston Trio and The Brothers Four and all of that kind of music was big, so I played those records. Then, Bob Dylan came out and I played his music as well. But, there was also a guy on campus that played the banjo and I gravitated to it because I loved the sound of that instrument. So, whenever I would find a record with a banjo on it, I would play it on the air. I started playing bluegrass on my radio show before I knew what it was. Then, like most people, I saw Flatt and Scruggs on The Beverly Hillbillies TV show and The Dillards as The Darling Family on the Andy Griffith Show. Earl Scruggs and especially The Dillards became two of my main influences.”

In fact, it was The Dillards that turned Friesen’s head around the most when it came to bluegrass music. “If it wasn’t for The Dillards, I wouldn’t be doing this for 50 years,” said Friesen. “In 1966, when I was in my third year of college, I changed from a folk music show to an all-bluegrass show because I met a guy named Mike Theobald. Mike’s dad was Jack Theobald, who started the first bluegrass band in Kansas. Mike was a banjo player who was heavily influenced by Doug Dillard. I was in class one day, and he was walking around and carrying a banjo and I said, ‘Oh wow, folk music.’ When I talked to him, he said, ‘Well, let me tell you, what I play is bluegrass music.’ I said, ‘Do you want to be on my show?’ Mike then brought his dad out to the radio station and we mic’ed him up in the studio and with just a guitar and banjo, they played for me a whole set of banjo tunes with no singing. Then, Mike would bring me records by folks like Bill Monroe, Jimmy Martin, Flatt and Scruggs, Jim and Jesse, the Stanley Brothers and all of the original acts.”

By this time, Friesen knew exactly what bluegrass music was, and he loved it and could not get enough of it. He started to buy every bluegrass record he could find, building up his own collection.

Because Friesen lived in Kansas, he was at the first-ever Walnut Valley Music Festival in Winfield, Kansas, in 1972. Shortly before then, Friesen had joined the bluegrass band called Prairie Grass, which consisted of himself and three former rock musicians who wanted to play bluegrass music. All of them were inspired by the 1972 release of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s landmark Will The Circle Be Unbroken recording, which became Friesen’s favorite album.

When Prairie Grass attended the first-ever Walnut Valley Festival, the organizers had a slot open for an act to play on its one and only stage. At that moment, no other bluegrass groups were on the grounds except for Prairie Grass, so they got the call. Therefore, Friesen and crew became one of the groups that officially played at that first Walnut Valley Festival.

A couple of years later, Friesen joined Jack and Mike Theobald’s band Bluegrass Country as a mandolin player, and then he switched over to the bass. Friesen would play with Bluegrass Country for the next 18 years. Through the years, Friesen would perform in bands that played other types of music as well while still maintaining his amazing run as a bluegrass DJ. Since the 1990s, for example, he parlayed his love for all things cowboy into joining a western band. Called The Prairie Rose Wranglers at first, and then eventually changing their name to the Diamond W Wranglers, Friesen and crew have played at Carnegie Hall twice, have even toured China and they have recorded over 20 albums.

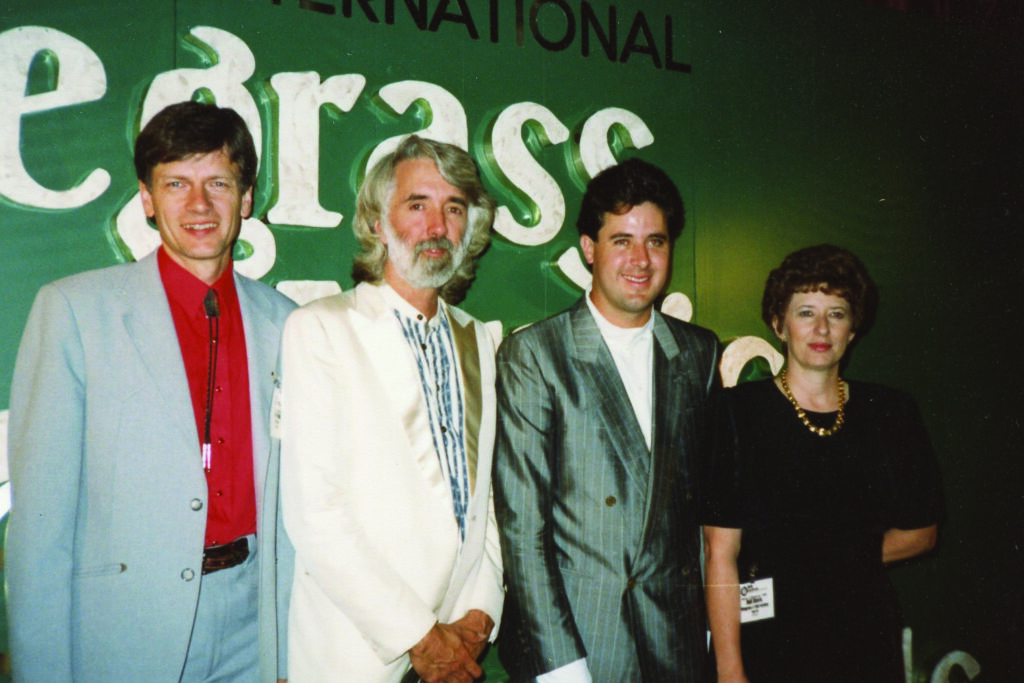

Friesen’s involvement with bluegrass extends beyond being a radio DJ, however, as he was a part of the early days of the IBMA organization and those first IBMA Award shows. “Along with Dell Davis, I co-produced the first ten IBMA Awards shows from 1990 through 1999,” said Friesen. “It started in Owensboro, Kentucky, and then the show moved to Louisville. Then, I had to drop out from being a producer because that is when I began to play music full time. The whole thing came about because Dan Hays, who is one of my best friends in bluegrass, said around 1989 or so, ‘We need an awards show for bluegrass music.’ That is when he gathered up Dell and myself and we created the initial concept for the IBMA Awards show. So, we looked at how they did the country music awards and the Grammy Awards and tried to figure out what all of the awards shows were doing, and eventually we came up with the original award categories. Then, Dan says, ‘Ok, now you guys need to produce this show.’”

Friesen and Davis’s response to the proposition of producing a music awards show was a negative one. “Dell and I hated awards shows,” said Friesen. “We said, ‘We don’t like the idea of saying that so-and-so is better than someone else.’ Then, Dan told us that it wasn’t about the winning, it was about making bluegrass known to the greater public, giving us an event each year that would raise the interest in the music. So, the whole point of the IBMA Awards show when we started was to make a big splash for bluegrass music once a year, and it worked.”

Then Friesen and Davis went about the task of finding a host for the first IBMA Awards show. “I talked with all of these people in bluegrass music and nobody wanted to host this show,” said Friesen. “So, I had known John McEuen from the Nitty Gritty Dirt band for a while by then and I asked him if he would like to be the host and he said, ‘Sure.’ Then I asked Vince Gill, who I had known since he was a teenager, and he said, ‘Yes, I’ll do it.’”

With Friesen playing bluegrass and broadcasting a radio show in Kansas back in the day and Vince Gill playing in his first bluegrass bands in Oklahoma, the two legends crossed paths early on. “Oh my goodness, Orin goes back to my childhood,” said Vince Gill, who called in from Amsterdam, Netherlands, while on tour with The Eagles. Gill’s latest album, appropriately enough, is called Okie. “Orin and I knew each other through bluegrass and he was from Wichita and I was from Oklahoma City and we would see each other at festivals all of the time. I was in two bands in Oklahoma, including The Bluegrass Revue and the other one was called Mountain Smoke. Each band was drastically different from the other. The first band was filled with all of the hotshot kid pickers of that area, with Bobby Clark, Billy Perry and his brother Mike. The Mountain Smoke band was made up of jug band pickers that loved bluegrass but weren’t great at it, yet they had more fun than anybody in the world. Those were during my high school years. The truth is, Orin has championed me from day one. He is a good man.”

Those first IBMA Awards shows were not as easy to produce as now because the technology in 1990 had yet to reach the levels that currently exists. “You know how they run small soundbites during the awards show, before, during and after each nomination and awards segment?” said Friesen. “Nowadays it is done in a computer. But back then, we had all of those on those audio cartridge tapes called carts. So, I had to have huge boxes full of these things while I sat backstage by the sound guy and I had to put them in and out of the cart machine as the show went on. Whenever they announced a winner, I had to grab the cart with their name on it and drop it in to play it right away. One year in Owensboro, right before the awards show, the delivery service lost our box full of carts. I had to go to the radio station in Owensboro and re-record everything and get each cart done in time for the show. It was a mess.”

After all of these years in the bluegrass world, Friesen is positive about where the music is now and where it is going. “It seems like bluegrass is stronger than ever because I just love Billy Strings and I love Molly Tuttle and those kinds of young artists,” said Friesen. “In my opinion, their music is the real deal. Billy Strings will come out and play onstage and he knows every Doc Watson tune that there probably ever was, and thousands of people are dancing to it, and I just love that. As for my radio show, because it is now broadcast over several outlets and streamed around the world, once in a while I will hear from somebody that lives in a foreign country who listens in, and that is wonderful.”