Home > Articles > The Tradition > Bobby Osborne

Bobby Osborne

Mourning the Loss of a Legend

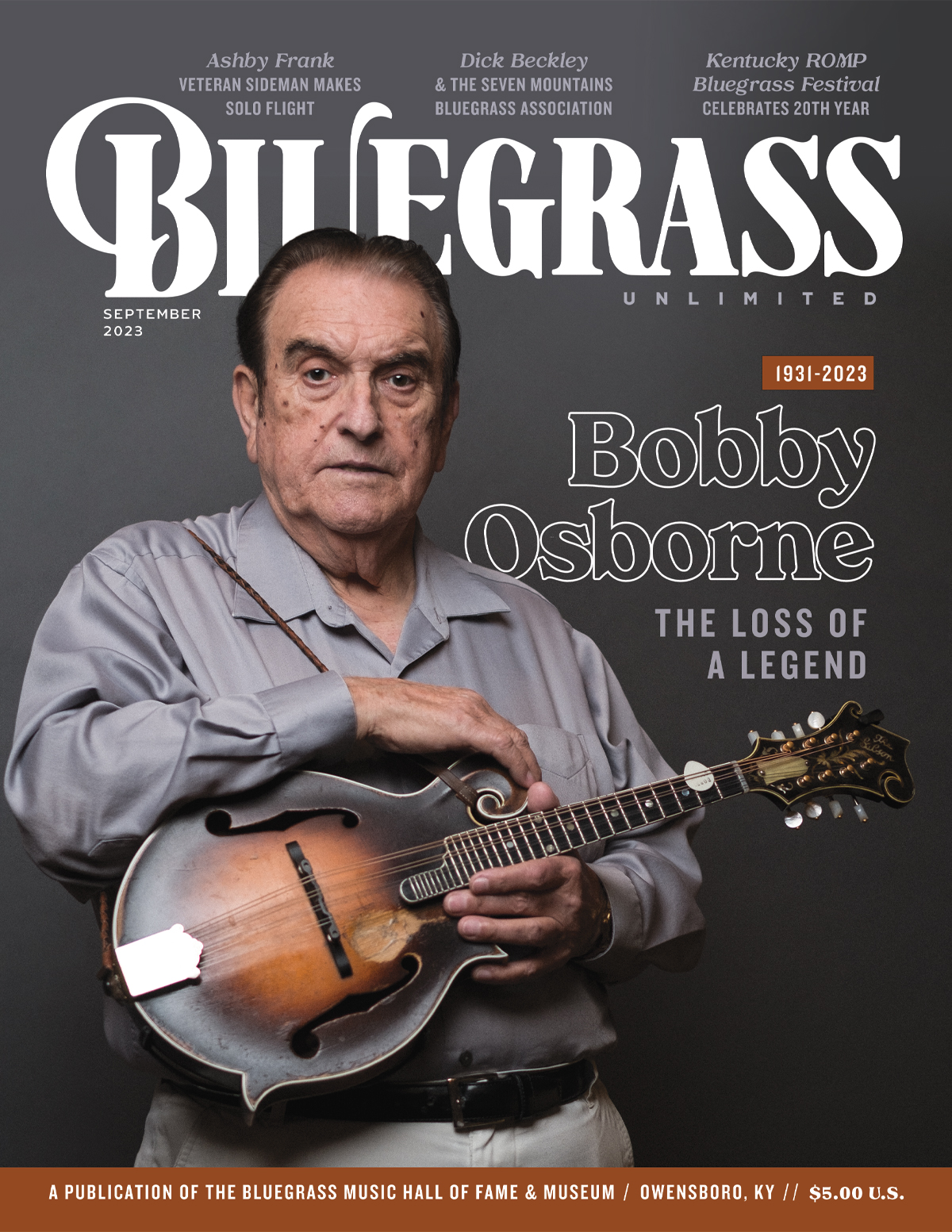

Photo By Scott Simontacchi

The world of bluegrass music mourns the loss of one of its iconic figures with the death of Bobby Osborne. He passed away on June 27 at the age of 91 just four days after his friend—and another legend of the genre—Jesse McReynolds, died. For more than half a century Bobby’s talented tenor voice and innovative mandolin playing made history alongside the masterful banjo playing and baritone singing of his brother, Sonny. The siblings paired together with an enviable career that challenged the traditional barriers of bluegrass while winning them admirers in country music circles.

Members of the IBMA Hall of Fame, Bobby and Sonny formed their partnership in 1953, and through the following decades became the first nationally renowned bluegrass group to amplify their instruments with electric pickups, the first to record with twin banjos and the first to include electric bass, drums, and pedal steel guitar in the bluegrass sound. They were Country Music Association’s Vocal Group of the Year in 1971, and the brothers scored 18 songs on the charts including their most famous one, “Rocky Top.” But perhaps, for Bobby, his most notable achievement was fulfilling the dream of membership in the Grand Ole Opry.

After Sonny’s retirement in 2005, Bobby embarked on a solo career with his band, the Rocky Top X-Press. The eldest Osborne also secured another IBMA Hall of Fame award for his role in the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers, a group he performed with prior to banding with his brother.

I had the honor of talking with Bobby Osborne on several occasions starting in the 1990s for feature segments on the Osborne Brothers for The Nashville Network and for stories in Bluegrass Unlimited magazine, and I had been working with him for several years on a memoir of his life. Segments of those personal talks are included in this story.

Life on Rocky Top

A child of The Great Depression, Bobby Osborne was born on December 7, 1931 on top of a mountain in his grandmother’s house in Thousandsticks, a rough four miles northeast through the mountains from Hyden, Kentucky. His dad, Robert Osborne, Sr. was a school teacher in the area, and his mother, Daisy Dixon, also taught for a while but gave it up to raise her children.

“When I was 7 years old, my dad bought me an old Regal guitar made in Chicago from an old boy down the creek for $30,” Osborne said. “When my dad got the guitar, he showed me three chords on it. The guy wanted $35 for it originally, but my dad talked him down to $30. He thought it was terrible he had to pay that much.”

About the time Bobby was in 4th grade, his dad moved the family to Dayton, Ohio where his oldest son stayed glued to the Motorola in the living room, listening to the Grand Ole Opry. “One of those nights when I was listening to Ernest Tubb on the Royal Crown portion of the Opry, announcer Louis Black said, “Here’s Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys!” I never heard anything come through a radio like that in my life! What is that? I asked my dad. That’s the banjo, he said. ‘Not like any banjo playing I’ve ever heard.’ Earl Scruggs kicked off “Cumberland Gap,” and I don’t know what came over me right there. After they finished, I thought to myself: ‘It’s impossible. There ain’t no way one guy could do that!’”

Osborne saw for himself when he persuaded his dad to take him to Memorial Hall to see Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys (Russell “Chubby Wise, fiddle, Cedric Rainwater (Howard Watts), bass; Lester Flatt, guitar, and Earl Scruggs, banjo) “I’ll never forget the first thing they played when they came out. It was the “Orange Blossom Special.” They were as electrifying performing in person, even more so than the music I heard them record for Columbia Records. When Earl Scruggs turned around to the crowd with his banjo for the first time, you couldn’t hear what he played because the audience was cheering so loudly. You couldn’t even hear yourself talk. When the band took an intermission, Monroe and Flatt continued to stand on stage performing while the other guys went through the crowd selling songbooks. I moved down front close to the stage so I could see Earl Scruggs play “Cumberland Gap” for myself. I still didn’t believe one man could really do all that music on a banjo, but he gave me an education in two minutes on exactly how that was done. I fell in love with bluegrass music right there.”

Originally, Bobby had planned to ply his vocal talents to singing like his idol Ernest Tubb. “When I turned about 15 or 16, almost from one week to the next, my voice jumped up to where I would sing Tubb’s same songs but an octave higher than he did. A lot of times a boy’s voice drops lower but not mine. I don’t know why it happened like that, but the man upstairs seemed fit to do it for one reason or another. It bothered me when my voice changed like that because I wanted to sing like Ernest Tubb. I knew his songs, but now when I sang them, they no longer sounded like Ernest Tubb. I had to accept it. That’s the only way I can sing, so that’s got to be it, I thought. The change in my voice gave me a chance to find my true voice as Bobby Osborne.”

And what a voice it was! He first got significant attention when he performed “Summertime is Past and Gone” on June 3, 1949, at a tent show on the grounds of radio station WPFB in Middletown, OH. “People were screaming and hollering. I had never seen people act like that before. We got off the stage. We got such applause that the emcee said they want you to do another song. I said, ‘We don’t know another song.’ He said, ‘You’ve got to know another one if you learned that one. Didn’t you learn another one?’

“I thought back to my time in Hyden, where my aunt had a little restaurant, Wood’s Café. It had a big jukebox in the middle of the floor. The first recording I remember hearing there was Bill Monroe’s original recording of ‘Footprints in the Snow,’ but there was another song that used to play there from daylight to dark by a lady named Cousin Emmy and her kin folks. She was a clawhammer banjo player, and a member of Renfro Valley Barn Dance. I learned that song from hearing it played in that little café so many times, but I had never tried to sing it. That was before I even thought about singing on stage. I never even did write the words down. Me and them guys went out there again on stage, and I sang ‘Ruby (Are You Mad at Your Man).’ Here comes the manager of the radio station, Randy Daly. He was a big heavy set guy. He came out and said, ‘Who sung that stupid song, ‘Ruby’ while ago?’ Boy, I never opened my mouth. I was scared to death. I was afraid he would say, ‘You get out of here. I don’t want to hear that no more!’ He repeated, ‘I want to know who sung that song, ‘Ruby.’’ Finally, I said, ‘It was me.’ He said, ‘I want you to get out there and sing it again. I’ve got five calls saying they’re going to turn off the radio if you don’t sing it again.’ I went out there and sang it again. I never will forget when I left that night that they gave me $4.00 for singing. That started a brand new ballgame for me.”

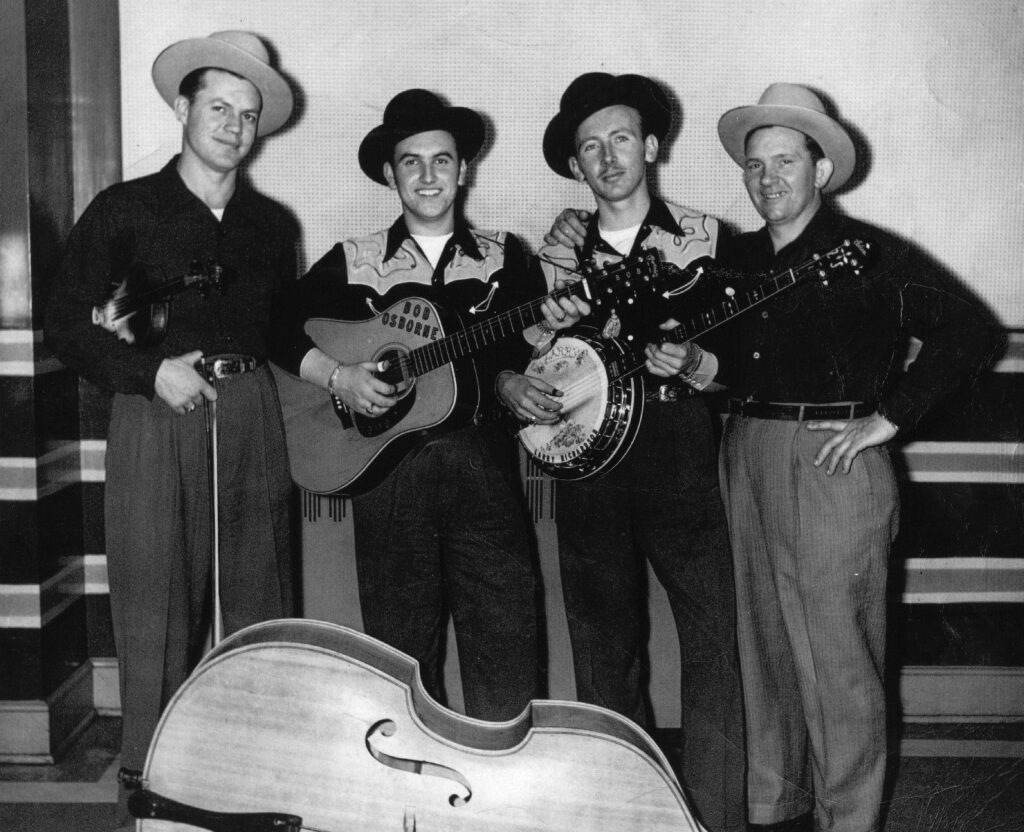

Eventually, Bobby dropped out of high school and hit the road with banjoist Larry Richardson. The two hooked up with the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers and for a few months Osborne did some fill in work with The Stanley Brothers. But it wasn’t long before Uncle Sam came calling. He was inducted into the Marines on the 23rd draft on November 27, 1951, ten days before he turned 20 years old. “I didn’t want to go to the service because I had a good start in music. I didn’t want to quit my career, but I had to make up my mind. Be a man or be a chicken. I wanted to be a man.”

While Bobby was fighting in the Korean War, his brother, Sonny was honing his skills as a banjo player and the teenager had a short stint as one of Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys. Two years later Bobby, who was wounded in action, returned home from service as the recipient of a Purple Heart, and he and his brother formed the Osborne Brothers. They performed their first show on November 6, 1953 at WROL Radio in Knoxville, TN. “As kids, we never talked about it [a career as a brother act]. We didn’t have to rehearse any until we got going with a band. It probably sounded terrible, I guess,” Bobby recalled, laughing. “We worked awful hard at it to try to get it to sound right.”

On July 1, 1956, The Osborne Brothers and Red Allen made their first records for MGM, which included the jukebox favorite, “Ruby.” Two years later the brothers hit the charts for the first time with “Once More” featuring the new trio sound they developed while driving back one cold February night from an appearance on the Wheeling Jamboree. “I just started singing the thing in a higher register, just as high as I knew how to sing it and make it the regular lead to the song. Red, being a tenor singer, knew where the tenor was, but he had to sing a lower tenor. Sonny did the middle part. We knew right then that we had come on to some kind of harmony that we had never heard from anyone in the entertainment world before. It was so pretty and precise in the parts. People knew it was different bluegrass than they had ever heard. People bragged on it all the time.”

Although Bobby and Sonny loved performing, they were having a hard time paying the bills. Just when they were about to throw in the towel, Bobby remembered Doyle Wilburn had given him a business card, offering help. Sonny gave Wilburn a late night phone call and within a week the brothers had several choice gigs lined up. In time, the Wilburns helped the Osbornes achieve their dream, membership in the Grand Ole Opry. “I never will forget that night. You’ve got all the Opry cast there. You’re on the 8 o’clock show, one of the biggest shows on there at the prime time of night. All the other members wanted to see what the new kids on the block could do. I never will forget. I was about halfway through ‘Ruby’ and Sonny was taking a break on banjo. I was afraid to look around. I was concentrating on the song. I turned around and looked and there stood Lester Flatt watching us and Ernest Tubb was back there watching. All the members were standing there watching. I tell you what. I about melted down! Everybody who was a member of the Opry was a hero of mine. As I finished singing ‘Ruby,’ I got to thinking that where I’m standing is where all my Opry heroes had stood. If that doesn’t get the best of you, nothing will. To finally get a chance to become a member, it’s like becoming President of the United States.”

The Osborne’s career hit “Rocky Top” came along on a timely release date, Christmas Day of 1968. Masterful songwriters Felice and Boudleaux Bryant delivered the gift to the brothers, but The Osbornes thought it needed to be rewrapped a little bit differently. “Sonny went over to his house and heard Boudleaux sing it real slow. We had recorded one called “Roll Muddy River,” and The Wilburn Brothers did it the same way he was doing “Rocky Top,” real slow. They played it slow and sang it slow. We sang it slow and speeded up the tempo, and that made it a different song.”

Still, it looked like “Rocky Top” was going to be neglected by radio stations because it was on the B side of the single. “Ralph Emery had the all night dee-jay show at WSM. Sonny and me went up there one night to be a guest on his program. He said, ‘I’ve never heard the other side of it.’ He told the audience, ‘I’ve been playing the A side of this. I’m going to play the B side tonight and see what it sounds like. Anybody like the B side better than the A side, let me know and I’ll play it.’ When he heard ‘Rocky Top,’ that was the end of the other side. All the calls he got wanted to hear “Rocky Top.”

Bobby and his brother continued to make waves of success in the bluegrass and country world not only at home but across the ocean too, much to Bobby’s surprise. “I never thought that people would like anything we did over there. When we went to Germany, there was 41 different bands. We played 11 different cities. Faron Young was going to be the headliner. They had us closing the first half. Twenty minutes was all that was allowed because there were so many people on the show. The first night we played near Frankfurt, a base where a lot of the Americans were stationed there. Sonny would get about halfway through his instrumental he was playing. Where the people were sitting out there you couldn’t see it. It was all dark. You’d just hear a roar. It sounded like an airplane taking off. Then, we’d do ‘Country Roads,’ and that roar would come again. It sounded like an airplane taking off. Once we did ‘Rocky Top,’ they wouldn’t let us leave the stage. They had an intermission then anyway, and Faron would come on. A lot of those nights Faron would be on stage, and they’d be out there hollering for him to sing ‘Rocky Top’ and ‘Country Roads.’ We really got scared to death. The promoter didn’t know what to do. I’ve never seen anything like that before. The people went wild! Faron had to threaten to quit and go home after about the seventh night. He said, ‘I ain’t gonna follow that!’”

Sonny decided to bow out of the business in 2005, but Bobby had no desire to give up what he loved. He continued on with his group, the Rocky Top X-Press. In 2017, Osborne at age 86 scored his seventh Grammy nomination—his first as a solo artist—for Best Bluegrass Album for Original. “I had just about come to the end of my career in music. The new people come in and they just kind of shove the old people, the ones that’s still left, out. The new people come in and take it over, and there’s nothing you can do about it. The thing that saved me was Alison Brown and Compass Records. She had the confidence in me to do a CD. Had it not been for Alison I wouldn’t have had anything left.”

From his humble beginnings in a poverty-stricken Appalachian town to a pivotal pioneer in the bluegrass world, Bobby Osborne’s significance to music can’t be overstated. The world is blessed to have experienced the music and the man. “I’d like to be remembered for the type person I am and what I’ve done. Just a plain, ordinary simple guy from a small settlement in Kentucky who made it big, or big to me. I want to be remembered as one of the guys. I’m so thankful that I have fulfilled a dream that I always had since hearing Ernest Tubb speak a word. Very seldom a person gets to make a living doing what you really want to do all through life, and I’m very thankful for that.”