Home > Articles > The Tradition > Notes & Queries – April 2022

Notes & Queries – April 2022

Queries:

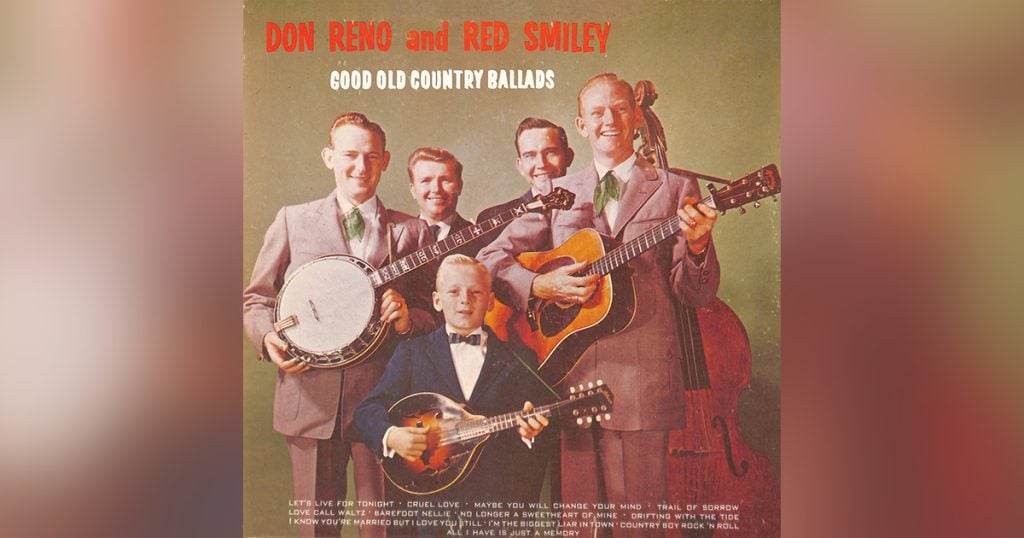

Q: One of my favorite albums by Don Reno and Red Smiley is one on King Records called Good Old Country Ballads. The back of the album jacket has a photo credit to someone named Fernandez. No first name. That has always struck me as odd. Do you know who he is or anything about him? BSR, Dallas, Texas.

A: You’re not the only one who has wondered about that credit over the years. Brian Powers, a Cincinnati librarian and King Records aficionado, made an ill-fated attempt to unravel the mystery of the photographer listed simply as Fernandez. He wrote, “I found this guy who lived below him in the late ‘50s. He started to get into photography because Fernandez lived above him. Fernandez would do photo shoots in his apartment. The guy took a bus ride to New York and Fernandez let him borrow a camera. So, this guy took some photos on his trip and Fernandez used them for album covers!”

After doing a little of my own detective work, I located the photographer’s daughter-in-law who was able to confirm that his whole name was Emanuel Everett Fernandez II, and that he usually went by Everett. He was, at times, a freelance artist, photographer, and writer who had the distinction of taking several album cover photos, including the Stanley Brothers first album release on King Records, The Stanley Brothers and the Clinch Mountain Boys (King KLP 615) and jazz/rhythm and blues player Bill Doggett’s Hold It! (King KLP 609).

Fernandez (March 16, 1916 – April 7, 1985) was a native of Galveston, Texas, who took somewhat of circuitous route getting to Cincinnati. Throughout the 1940s, he held a number of jobs, starting with the Alert Advertising Agency. He later held a position at the Houston Post and taught advertising and art at Southwestern College. On the side, he served as president of the Cigma Magic Society. The late 1940s found Fernandez back at Alert Advertising, where he was a commercial artist. It was in 1949 that a new job opportunity took him to Cincinnati. He began his life there with a new wife, Betty Scott Owens, whom me married on November 20, 1950.

In the early and middle 1950s, Fernandez held down a position of art director at Crosley Division of AVCO Manufacturing Corporation in Cincinnati. It was while working at Crosley in 1954 that he spearheaded the formation of Creative Camera Artists of Cincinnati, “a band of amateurs and professionals not content to picture a tree as a tree.” Fernandez’s approach to photography was summarized as follows: “A creative photographer knows what he’s going to have before he takes it . . . he puts in as much time and study in the perfection of the use of light, shadow, composition, balance and background as does the professional artist in his preliminary layout.”

Eventually, Crosley got out of the business of manufacturing appliances and by the end of 1956, Fernandez kept busy doing freelance work. Among his creative endeavors was his Low Down on Hi-Fi and Catalog of Record Albums. In it, he announced three new speeds for record players: 16, 8, and 0 (“zero is for people who don’t like to listen to records”). In the catalog’s explanation of technical hi-fi terms, he defined “woofer” as “a man who puts woofs on houses” and “treble” as “what you can get into if you ask for it.” Among the albums he featured were I Could Have Lanced All Night, Isn’t it Rheumatic, and Somebody Stole My Gall. It was during this burst of creativity that Fernandez shot photos for King Records.

Fernandez’s freelance work came to an end in 1959 when he accepted a position in the circulation promotion department of the Cincinnati Enquirer newspaper. Some of his work at the paper was cited in an early 1960s edition of Screen Process magazine. His last-known professional work started in May 1965 when he became the art director for the Si Shulman Advertising Agency.

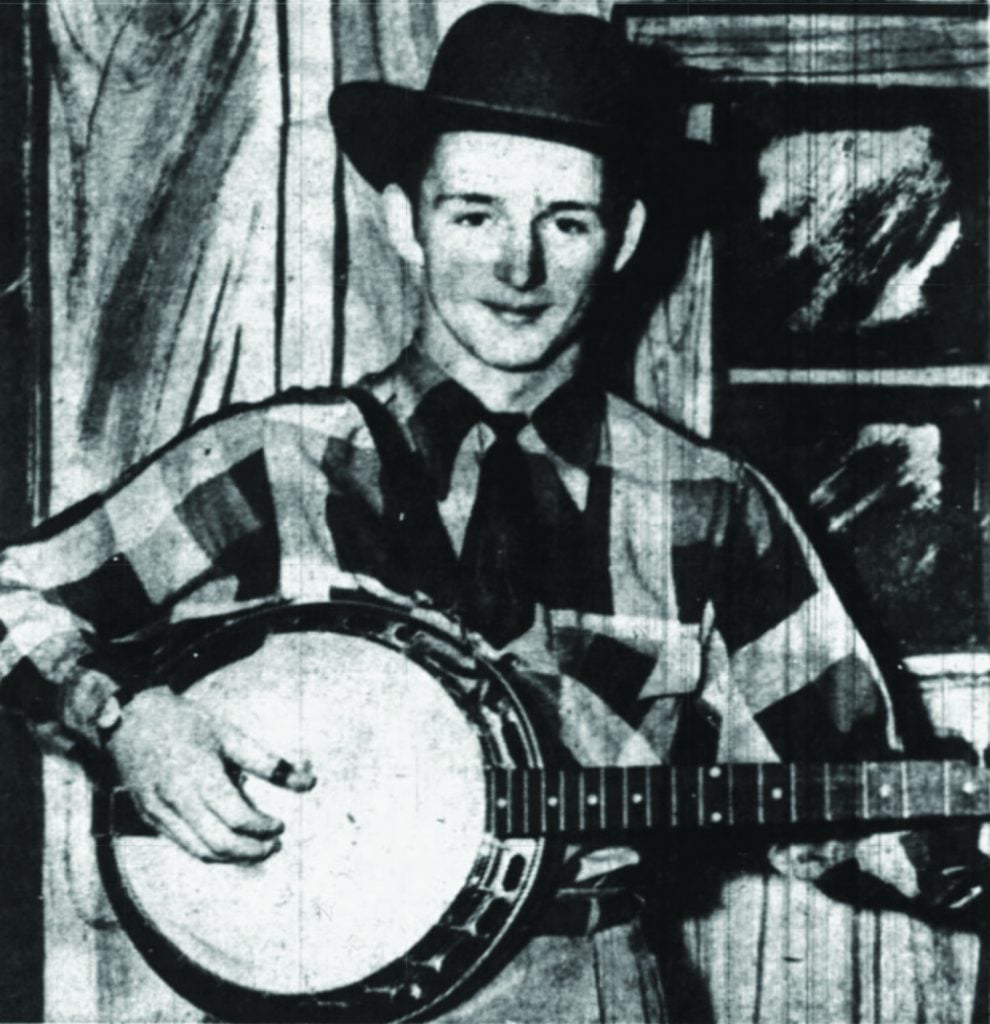

Forgotten Blue Grass Boy

Among lists for people who keep track of such things—in this case, musicians who rotated in and out of Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys—the name of Jack Perry is missing. Granted, his tenure was brief. But, he was there. An article in the January 20, 1955, edition of Perry’s home county newspaper, The Republic of Columbus, Indiana, related that he had climbed “to the top by joining Bill Monroe and his Blue Grass Boys, regular Grand Ole Opry performers.” But almost as quickly as he arrived on the scene, he was gone. The same article told that “if you’ve been missing your favorite hillbilly singer on the Grand Ole Opry the past couple of weeks here is the reason why—he exchanged his cowboy boots and 10-gallon hat for the air force

blue . . .”

Jack Lee Perry began life as Jackie Lee Bishop in Westport, Indiana, on January 16, 1936. He was the only son of Charles and Evelyn Perry Bishop. Jack’s mother died of tuberculosis on (or about) January 7, 1937, when the youngster was just shy of one year old. He went to live with his mother’s brother and sister-in-law, Louis G. and Lola Ochs Perry, and assumed the last name of Perry.

Jack began taking an interest in music around age nine, in about 1945. It was then he began learning to play Hawaiian and Spanish guitars. Three years later, he participated in a teenage amateur show that was held at an outdoor park in Columbus, Indiana. He performed electric guitar music.

In the summer of 1949, he competed in an amateur contest in nearby Seymour, Indiana. In the first round of the competition, he placed first by playing three selections on his Hawaiian electric guitar. Two weeks later, at the competition finals before an estimated crowd of 5,000 attendees, Jack again performed three selections on a Hawaiian steel-stringed guitar and was awarded third place, which carried a cash prize of thirty dollars. That same summer, Jack performed at nearby localities and even sported a spot on WCSI-FM.

Later that fall, one of Jack’s appearances took him to the residence of Mr. and Mrs. Webb Moss where a meeting of the Bartholomew County Saddle Club was being conducted. It was there that “Jack Perry, Columbus, provided music.” He made a return appearance at the Webb residence in June 1950 where, with Keith Thompson and David Moss, he again provided music. Of special import is the fact that Mr. and Mrs. Moss were the parents of Jack’s future wife, Norma Jean Moss.

Throughout the summer of 1951, Jack performed as part of a group known as the Indiana Ramblers. It was sometimes billed as Jack Perry’s Indiana Ramblers. The group appeared to be a duo consisting of Jack and Keith Thompson but they sometimes included additional musicians such as Fred Maynard, Judy Sweet, and Roschia Hohenstreiter. One prominent engagement took place in October 1950 when Jack and Keith journeyed to Cincinnati to appear on WKRC-TV.

An item in the December 8, 1950, edition of The Republic contained a brief paragraph that announced Jack’s first professional work: “Jack Perry, 16-year-old son of Mr. and Mrs. Louis Perry, 217 Fifth street and a talented musician, has hit the big time. He signed early this week with ‘Texas Slim’ Rogers and his Pals of the Purple Sage and has departed on a tour that will include stage, television and radio appearances. Jack . . . has played over local radio station WCSI and over Seymour station WJCD. Texas Slim’s outfit played at Hope’s theater last night. They will appear in Bloomington Monday, Sullivan Tuesday, Winchester Wednesday, New Castle Thursday, Elwood, O., Friday, Cincinnati Saturday and Lima, O., Sunday. He was formerly a member of the Indiana Ramblers.”

However, by February 1951, newspaper notices made mention of appearances once again by the Indiana Ramblers. Most of their performances were community-oriented events that included entertaining patients at the nearby Camp Atterbury Veterans hospital and a PTA fundraiser.

At some point in this 1948-1952 period, Jack also performed on radio with Harold Lowry, a local up-and-coming bass and guitar player.

In the early part of 1952, Jack came to the attention of Bob Hardy, the driving force behind the Hayloft Frolic, a jamboree type program that was broadcast on WTTV-TV in Bloomington. Jack remained a part of the program’s cast for nearly three years, playing banjo. At the same time, he did double-duty as part of the house band at Bill Monroe’s Brown County Jamboree in Bean Blossom, Indiana.

In the latter part of 1954, Jack became a member of Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys. He made several appearances on the Opry as part of Monroe’s group. But, as mentioned earlier, in early January 1955, when Jack was just shy of his nineteenth birthday, he joined the Air Force for a four-year hitch and was sent to Lackland Air Force Base in Texas.

While home on leave in the summer of 1955, Jack ventured to the Brown County Jamboree. The Stanley Brothers were the featured attraction and Jack managed to share the stage for one song: “Those Bitter Tears.” (Banjoist Larry Richardson, a mid-’50s regular at the Jamboree, recorded the song a decade later.) Jack’s solo was recorded on reel-to-reel tape, as was the rest of the show; it represents some his only known performance work.

In June 1957, while stationed in Japan, Jack was able to take part in a Hayloft Frolic tour that included thirty-five days in California, Honolulu, Wake Island, Japan, Korea, Formosa, Okinawa and other points where American troops were stationed. It is doubtful that Jack participated in any performances that took place stateside and more likely appeared in Japan and Korea.

After Jack’s discharge from the Air Force, he spent the next twenty-five years as a truck driver for Moon Freight Lines and Whiteford Trucking.

Jack continued to keep a hand in music. Neil Rosenberg wrote:

On Sunday August 20, 1961, Jack Perry was a contestant in a banjo contest held at the Brown County Jamboree. He was accompanied by Bryant Wilson on guitar, and played “Cumberland Gap” and “Home Sweet Home.” The other contestants were Art Rosenbaum (he played “Bile Them Cabbage Down” and “Old Scolding Wife”), accompanied by Shorty and Juanita Shehan, and the twin banjos of Pat Burton and Neil Rosenberg (playing “Cripple Creek” and “Bury Me Beneath the Willow”), accompanied by Ann Burton Williams. Rosenbaum took first place, Burton & Rosenberg second, and Perry third.

Following the contest, each of the contestants performed with the house band. Perry and Wilson were joined by Shorty; they did “Little Darlin’ Pal of Mine,” a vocal trio with Bryant singing lead, Jack doing tenor and Shorty singing baritone. Their second number was “Stand Still,” a vocal solo by Jack, and they closed their segment with the instrumental “Choking the Strings.”

Throughout the early 1960s, Jack made annual appearances at community-sponsored music events at Donner Park in Columbus, Indiana. In the middle 1970s, he was a regular participant at Muncie, Indiana’s Green Hill Follies. He passed away on January 29, 1997, in Indianapolis. He was sixty-one.

For the Good People

On January 3, 1975, I purchased the Stanley Brothers album For the Good People (King Records KLP 698). It was recorded in September 1959 and was released in 1960. Many times over the years, I asked myself, “I wonder that front cover photo was taken?” I made several ill-fated attempts over the years to locate it. Looking on-line at hundreds of photos of old, wooden, white, country churches proved to be a futile endeavor. Given that King Records was located in Cincinnati at the time of the album’s release, I thought, perhaps, the church was located near there. No luck. And besides, the church on the album cover had somewhat of a New England look about it.

Just recently, and still curious, I thought I would give it one more try. I started another Google search for “old, white, wooden churches.” After about five minutes, I came across one that caught my eye. The photo was taken from a completely different angle, but several of the features looked similar. I quickly retrieved my copy of the album to compare it to the photo I had found on-line. Sure enough, it was a match. Just like the Arkansas traveler who asked his own question and then answered it, too, I was finally able to answer my own question. The church in question is the Congregational Church in Peacham, Vermont. 47 years later, mystery solved!

It’s likely that the cover photo was a stock image that the record company purchased for use on the album cover. It’s hard to imagine that King Records, located in Cincinnati, would have dispatched a photographer all the way to Peacham for a photo of an old country church.

The church’s website has some interesting history about the building: “The Olde Meeting House Celebrates its 215th Anniversary in 2021: The Olde Meeting House was built in 1806. The master builder was Edward Clark. To raise money to build the building, the Congregational Society held a public “vendue” or auction and sold pews. They raised $5,594. The church was built from local trees with axes, and oxen to drag the logs to the sawmill where they were cut into logs. Stones for the foundation came from the rocks and boulders that had to be removed from the fields. The original building was erected across the street from where the Peacham VFD building currently stands (across from the Peacham Cemetery). In 1844, the building was moved to its current location with the use of oxen and logs to roll it down the hill.”

Goodbye Maggie

While revisiting the splendid Bill Monroe collection on Bear Family, 1936-1949, I stumbled upon an interesting passage that related to a song recorded by the Monroe Brothers called “Goodbye Maggie.” In his excellent notes to the package, Charles Wolfe told that “Goodbye Maggie” came “from the singing of Karl and Harty, the two men from eastern Kentucky who had known the Monroes since their days on the WLS National Barn Dance [mid-1930s]. It appeared in the M. M. Cole songbook that Karl and Harty issued with the Cumberland Ridge Runners, and except for the added echo, the Monroes’ version is word-for-word like the printed text. Composer credits in the Cole book were to ‘J. Guest,’ of whom nothing is known.”

With lines in the song telling of “a soldier smiling bravely” and that “victory has been nobly won,” it was obvious that the song dealt with a war time situation. Given that the Monroe Brothers recording was made in 1938 and that they had recorded at least one other then-recent war lament (“Forgotten Soldier Boy”), it seemed logical that “Goodbye Maggie” told the tale of two lovers separated by the call of duty to serve in World War I.

What stirred my interest in Charles Wolfe’s notes was the addendum to “J. Guest” . . . “of whom nothing is known.” Turns out that J. Guest was John Guest, an English composer (ca. 1844 – March 18, 1907) who conspired with lyricist Harry Hunter (1841-1906) to write a song called “Annie Dear, I’m Called Away.” The song made its debut in England around 1873 and was performed in British music halls and as part of minstrel shows.

At some point in the early to mid-1880s, the song made its way to the United States, where it was, again, performed in minstrel shows. In 1885, a composer by the name of C. B. Coolidge changed the name of the song’s heroine from Annie to Maggie. The first recording of the song, however, remained true to the original. Blind Jack Mathis recorded “Annie Dear, I’m Called Away” at a session in Dallas, Texas, in 1928 for release on the Columbia label. It wasn’t until a decade later that the Monroe Brothers, at their last recording session together, in 1938, recorded “Goodbye Maggie.” The duo’s release on the Bluebird label gave songwriting credits to Charlie Monroe!

A number of old-time and bluegrass groups made use of the song over the years. Shortly after World War II, a time when the song’s theme no doubt struck a chord with a war-weary public, the Blue Sky Boys featured “Goodbye Maggie” on their radio broadcasts. In 1958, the husband/wife duo of Harry and Jeanie West released their version on an album called Smoky Mountain Ballads and in 1964 the Lilly Brothers, ardent fans of the Monroe Brothers, included it on an album for the Prestige label. More recently, the duo of Don Rigsby and Dudley Connell incorporated “Goodbye Maggie” into a 1999 release. The most current recording is a 2009 release by the New North Carolina Ramblers.

Over Jordan

Heather Dunbar (July 30, 1950 – February 7, 2022), a long-time resident of Ithaca, New York, was characterized by bluegrass broadcaster Bill Knowlton as a “bluegrass and Americana promotor, a radio deejay for many years, an emcee, and a writer.”

She began her career in broadcasting in 1978 when she took over “The Salt Creek Show,” which aired on commercial station WVBR-FM and was described as highlighting country & western music. In time Dunbar, brought her own musical sensibilities to the program and featured “the best bluegrass, country, honky-tonk and roots-rock.”

Radio expertise came naturally to Dunbar. In 2008, she told the Ithaca Times that “my father and my two brothers were disc jockeys, and if you’re talking about how a woman might have excellent attitudes and skills, and not be afraid of being on the air, it’s because it was okay in my family.”

Dunbar’s stay at the helm of “The Salt Creek Show” lasted for twenty-one years, starting on her birthday in 1978 and lasting until Easter Sunday in 2000. She left the world of commercial radio “to pursue projects in public radio” at WSKG in Vestal, New York.

Among Dunbar’s bluegrass experiences was the opportunity to emcee the artist showcases at the second annual IBMA World of Bluegrass event in Owensboro, Kentucky. Later, shortly after the passing of Bill Monroe, she organized a pot luck dinner/memorial that she likened to a Quaker meeting, where each guest spoke as the spirit moved them.