Home > Articles > The Archives > Rambling In Redwood Canyon: The Routes of Bay Area Bluegrass

Rambling In Redwood Canyon: The Routes of Bay Area Bluegrass

First of Four Parts

Part One Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

May 1991, Volume 25, Number 11

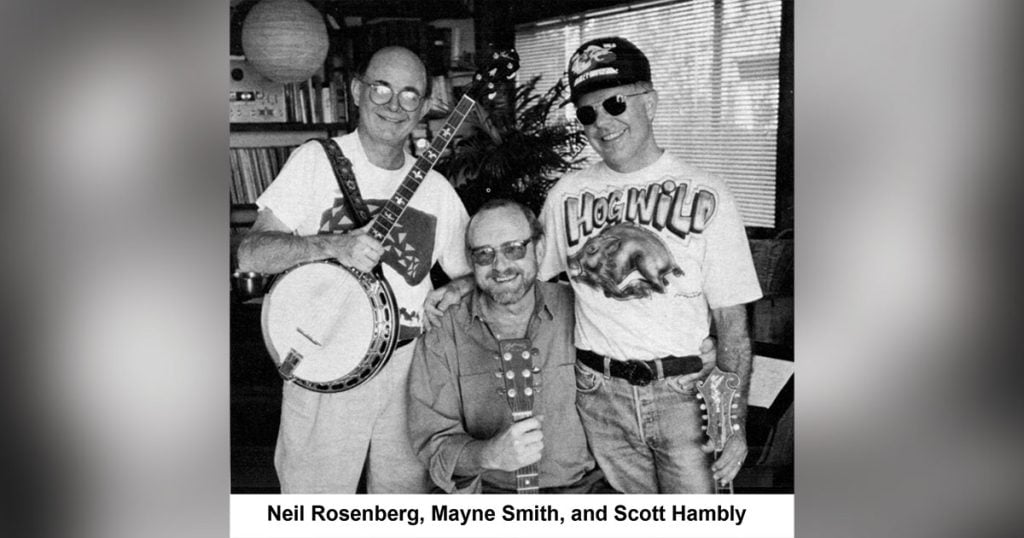

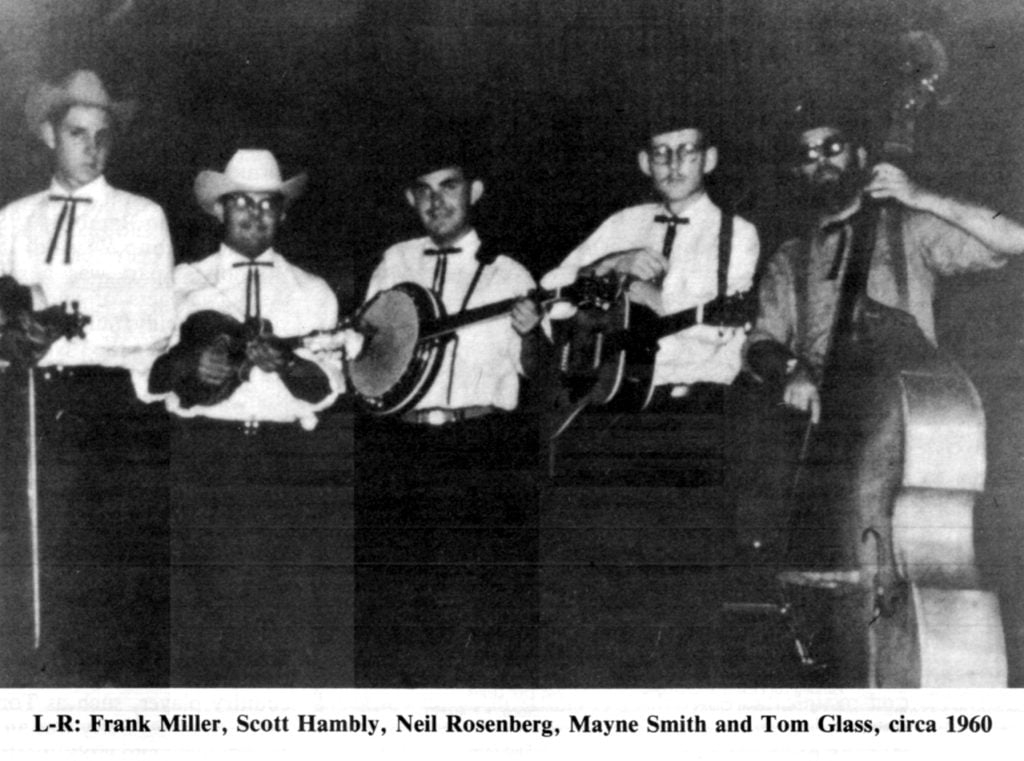

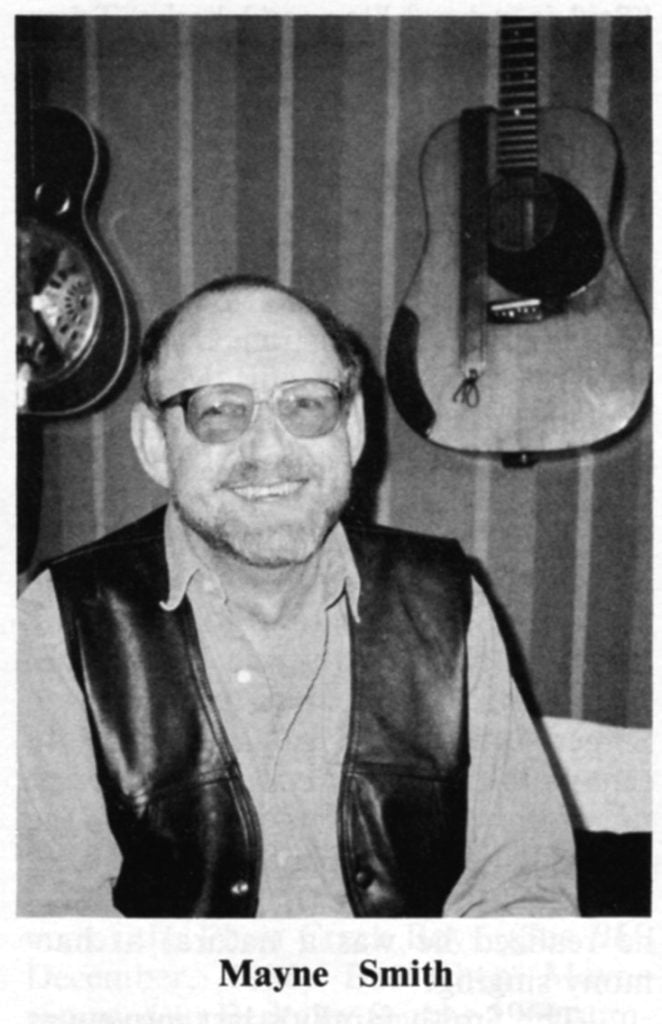

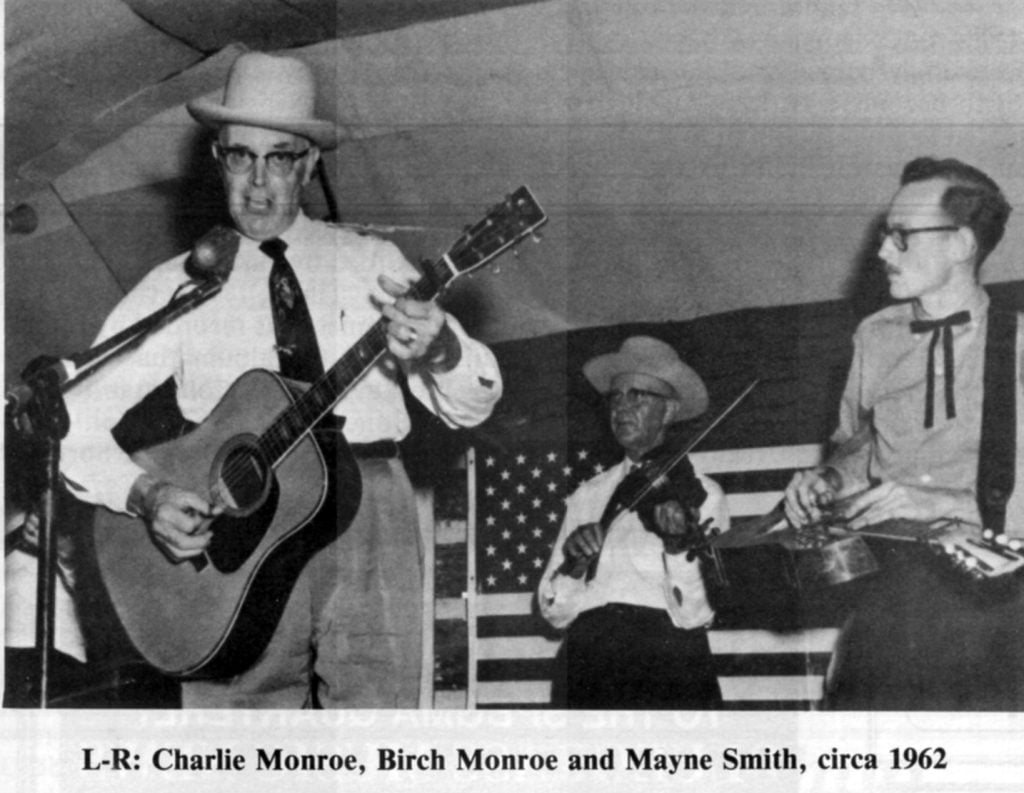

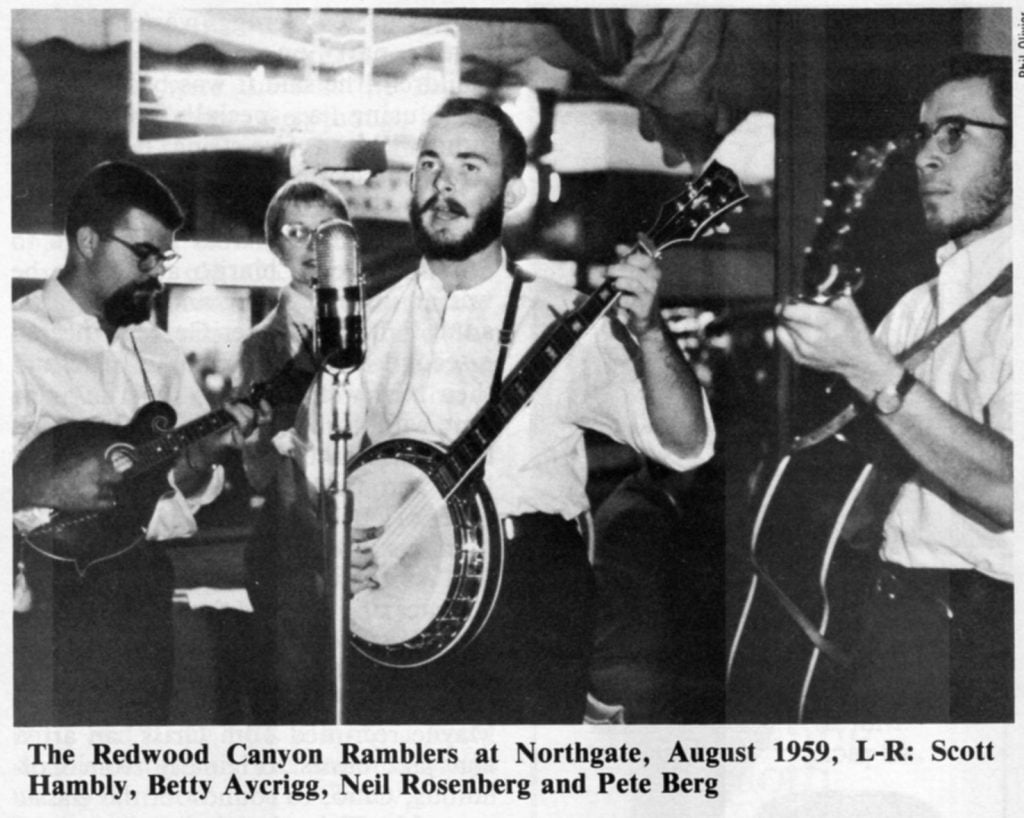

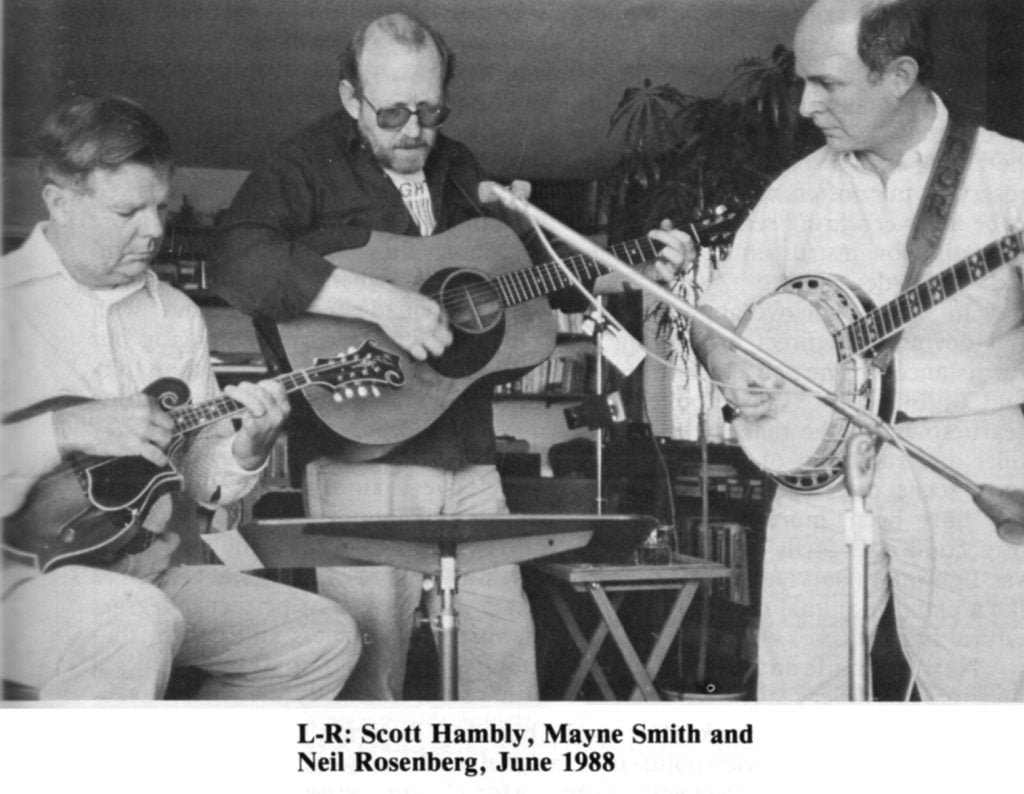

Once upon a time, in a land far from the birthplace of bluegrass music, lived a group of young college students who became the first bluegrass band in the San Francisco Bay area. It was the late ’50s. Mayne Smith, Neil Rosenberg, Scott Hambly and Pete Berg were the founding members. The first three made up the version of the Redwood Canyon Ramblers that gave Berkeley its first bluegrass concert, 31 years ago this year, on a late August evening. One of the band members has gone on to become a world authority on bluegrass music and the Bay Area has become a spawning ground for serious bluegrass musicians and acoustic musicians influenced by bluegrass.

Now, Mayne Smith designs computer manuals at a Fortune 500 company in Marin County and performs original music with Mitch Greenhill; Neil Rosenberg writes (including “Thirty Years Ago This Month” for this magazine), lectures, plays music and teaches folklore at St. John’s University in Newfoundland; Scott Hambly works as a medical editor at a military hospital in Oakland and Pete Berg plays salsa music and has a bamboo nursery on the big island of Hawaii.

What happened between then and now and how did they ever get started doing what they did?

It was mid-1960, a warm California evening, in a meeting hall near the U.C. Berkeley campus—a room full of folksong enthusiasts. I was the youngest in the crowd, about fourteen years old. Halfway through the night and the various singers and guitarists, one young man with a big Mastertone banjo was introduced. I don’t remember if he was accompanied or not, but he played “Flint Hill Special” using Scruggs pegs. Sudden consciousness of that sound is really all I can recover about that night, I don’t even remember getting there or getting home. In a small way I’m still there in that room, seeing that banjo tune played live for the first time. The memory has the character of a faint dream never quite forgotten.

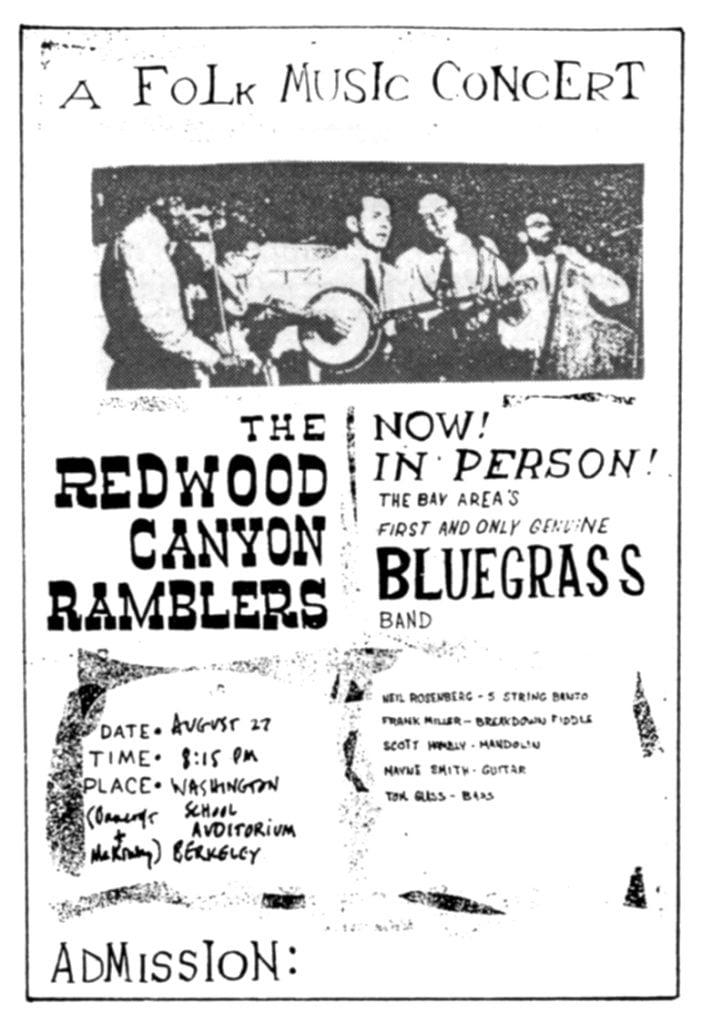

Then about a month later, in August, posters started appearing around town advertising “a Folk Music Concert—the Bay area’s first and only genuine bluegrass band, the Redwood Canyon Ramblers,” to be held at the Washington Elementary School auditorium on August 27, 1960 (at “8:15 p.m.”). The poster art was avant-garde even by today’s standards, with a mustard yellow background, solid black lettering, torn paper designs and high-contrast photo showing the five-piece band. The guy with the banjo looked familiar. I had to go to that concert.

If seeing Neil pick the banjo at that folksong club was unforgettable, the Washington School concert was life-changing for me and probably some others. It was my first real bluegrass show and was simply the most exciting live music I had heard up to then. As it turned out, it was also one of the last public appearances of the original Ramblers.

Writing in the Oakland Tribune on the 29th, the Monday following the Saturday night concert in Berkeley, jazz columnist Russ Wilson had this to say: “The quintet’s performance was a joy and left its audience of some 200 country music devotees shouting their approbation . . . Besides providing a lot of fun, the concert also exposed a segment of vital music that is heard infrequently in this area. The fact is, however, that the Ramblers shortly will start rambling in different directions. Neil Rosenberg, who plays the five-string banjo and Frank Miller, the breakdown fiddler, will soon depart for Oberlin College in northern Ohio. Guitarist Mayne Smith and Scott Hambly, who performs on the mandolin, will resume their classes at U.C. And bassist Tom Glass, a graduate of the Cleveland, O., Art Conservatory, will blend fewer sounds and more colors.”

Knowing nothing of all this at the time, I went up to Neil after the show.

“I want to learn how to play the banjo like you do.”

“Well,” he said, “I don’t really give lessons, but our guitar player does. He plays the banjo too. Talk to the guitar player.”

Disappointed, I walked away, then back. I spoke to the guitar player and he gave me his phone number and address on a scrap of paper—Mayne Smith, corner of Parker and Benvenue near the Berkeley campus. I knew the area well; it was just a few blocks from what had been Barry Olivier’s folk shop, the Barrel and was now Campbell Coe’s guitar repair shop, Campus Music Shop. I went to Mayne’s house a couple of times and he showed me some basic two-finger picking. He showed me the ‘gallop’ lick on the banjo, backed me up on guitar and loaned me an old-time banjo record. I still really wanted to study Neil’s banjo playing up close.

A friend of mine, Butch Waller, decided to take some lessons from Scott, the mandolin player and eventually I got a chance to go to Neil’s house with Rick Shubb, who had somehow scored a banjo lesson with him more than a year later.

Most of us beginners—Rick and I, Butch and his friend Herb Pedersen and others—went everywhere the Ramblers played, wherever we were old enough to get in, until September when Neil left to go back to college at Oberlin.

To start closer to the beginning:

Berkeley is a progressive university town next to Oakland and just across the bay from San Francisco. Mayne and Neil had met in 1954 as students at north Berkeley’s Garfield Junior High School at a time when a rich musical diversity was settling in the community. There was a healthy folk scene already going in Berkeley then. Both played the guitar. Two years later at Berkeley High they met Scott Hambly, who played drums and was getting into flatpicking blues and country guitar. There were a bunch of other kids also interested in music.

“A kind of scene developed between me and Scott and his friend David Crane,” recalls Neil. “All of us took guitar and voice lessons from Laurie Campbell, a folksinger we heard on KPFA, the local FM radio station.” Part of the Pacifica network that includes WBAI-FM in New York City, KPFA radio was and is a distinctive social and cultural phenomenon—as Neil called it, the ne plus ultra of Berkeley media culture. The group widened to include Mayne Smith, David Jones, Rita Weill, Tam Gibbs and Larry Hanks, among others. “We started having parties at John ‘Skinny’ Thomas’s grandfather’s cabin out in Redwood Canyon.” In California there are many redwood canyons, but this rural location just east of Berkeley and the Bay Area, long an artists’ and writers’ colony, is actually a town called Canyon or Redwood Canyon on some maps. Around 1850 it was a logging community famous for a rough-and-tumble bunch of teamsters known as the “Redwood Boys” who were credited with four hangings and never brought to justice.

For a bunch of urban high school kids in the 1950s, hanging out in a place like Canyon was great for getting away from city tensions, but it was more than that. Scott Hambly: “For me it was a way to get in touch with country life and that fit with the musical direction we were taking—country blues and country music.” Later, when it came time to name the group that Neil and Scott formed with Mayne, it was only natural that Scott suggested the Redwood Canyon Ramblers. “Scott named the group,” said Neil. The ‘Ramblers’ part was a reflection of their awareness of another bunch of young citybilly musicians on the opposite coast, the New Lost City Ramblers. ‘Redwood Canyon Rambers’ sounded like California, yet it also sounded like bluegrass.

The name stuck and except for a period during 1960 when Miller and Glass joined on fiddle and bass respectively, the three founding members often performed as a trio. Back in those days in California, especially in the Bay Area, fiddlers were nonexistent or extremely rare and bluegrass bass players were unheard of; one was sometimes recruited from a jazz or country player, such as Tom Glass or Betty Aycrigg. Betty was an experienced country and folk performer and member of the Gateway Trio under the name Betty Mann, who played with the band on some of their earliest gigs.

At the time, these young pickers may not have been aware that they were beginning to import bluegrass to the area and create an audience for it.

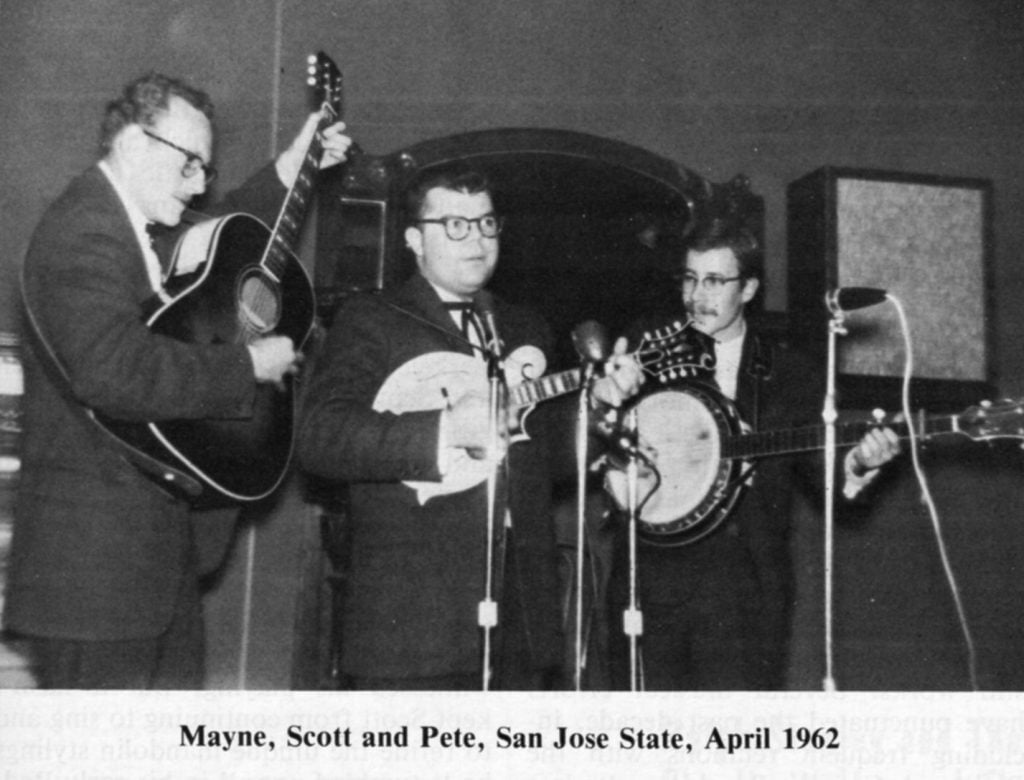

In terms of a core group that has stayed in touch over the years and still plays together at holiday gatherings, Mayne, Neil and Scott are that group. But historically speaking, Pete Berg has to be seen as the fourth founding member of the Redwood Canyon Ramblers—especially since the popularity of bluegrass music increased greatly during his tenure in the band. When you say “Redwood Canyon Ramblers” to anyone who listened to bluegrass around Berkeley after the fall of 1960, the banjo player they’ll remember is Pete Berg. In fact, Pete played washtub bass and sometimes guitar in some of the earliest versions of the Ramblers, but until 1963 or ’64, when he all but stopped performing bluegrass, Pete took over the banjo position after Neil left the area. So although the classic band had Neil on banjo, Mayne on guitar and Scott on mandolin, I consider Pete Berg an original member even though in his own estimation he only “filled in for Neil” or was added after the group was already formed.

And because the Ramblers—with either Neil or Pete as banjoist—were so often a trio without a bass player, they are, with Neil, comfortable even to this day as a trio. But they are a tight trio with tremendous power and synchrony, even after the intervening 31 years. They keep up their repertoire at reunion parties, picking sessions usually held at their parental homes in Berkeley during annual holidays or other special occasions when Neil might come to the West Coast from Newfoundland, a mere 5,000 miles away. There’s usually a bit of magic at these sessions. How can it be that three people separated for so long in time and space can still play together so precisely and harmoniously, with the high degree of attention and creative interaction that they have? It’s true that they were all born the same month, two in one year and one the next, but they all agree it’s probably because they learned music together and played together so intensely and with such concentration during their musically formative years, almost like three brothers.

* * *

In this grouping of principals it would be wrong to say that any one of them is more important or essential than any other. I don’t think you can replace any of them and still have the Redwood Canyon Ramblers, although Scott Hambly was willing to book a group under that name if it had at least two original members in it. But to me, within this equality, Mayne Smith is something like a musical center or nucleus around which the other members can form a whole; after all, this is not an uncommon attribute of a bluegrass singer and rhythm guitarist. With his dedication to the group ethic and to ultra-solid musical support on guitar also comes an inherent creativity within the bluegrass genre. Even though few of his original compositions have been performed by the Ramblers, songwriting turned out to be a natural for Mayne. If the band hadn’t split apart geographically and had continued on as a regular performing unit past 1964, I’m sure their repertoire would have included original songs by Mayne as well as instrumentals by Neil and Scott. At their continuing jam sessions and reunion parties, increasing now more than ever, originals are coming up for suggestion and experimental arrangement to complement their already unique musical vocabulary.

On the side of scholarship, it’s a notable fact that Mayne was the first person to publish serious studies of bluegrass music in scholarly journals. Neil Rosenberg is the first to point this out. But in his 1974 proposal for a planned special-market trade book to be titled Getting Into Bluegrass, Mayne writes autobiographically: “It was writing my own songs that drew me out of bluegrass and academe almost simultaneously in 1966. That got me involved in emotional and musical realities that suddenly made bluegrass and scholardom both feel too narrow for my needs. I haven’t gotten rich or famous since, but I’ve sure felt better.”

Loyd Mayne Smith—the Loyd was for his paternal uncle but never used—was born on March 15, 1939, in Boston, Massachusetts, just as his father, destined for eminence as an American literary historian, was finishing his doctoral studies at Harvard. The late Henry Nash Smith was a young star in a brand-new field called American Civilization, receiving the first Ph.D. granted in that program. The family immediately relocated to Henry’s home state of Texas for his job at the University of Texas in Austin and Mayne’s oldest sister Janet was born there two years later. This was followed by several other moves, to Cambridge, Pasadena, Minneapolis and Berkeley. “For some reason they just couldn’t hold still long enough for me to go to the same school for two consecutive years.” Mayne observes that this had a profound influence on his personality in a number of ways: “It sort of kept me as a loner and an outsider; I think I’ve always tended to kind of hover on the outskirts of whatever group I’ve been affiliated with since then. Another aspect of this maverick tendency was getting interested in something like bluegrass. By this time his father had published Virgin Land: The American West In Symbol And Myth, (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1950), which won the Bancroft Prize in History. The book, based on his thesis, dealt with the relationship between realities in the American West and what people thought the West was. With Henry closely connected to studies of popular culture and folklore, especially of the West, it follows that there was plenty of music around home to influence Mayne and Janet (an accomplished folksinger, songwriter and guitarist in her own right). “My mother played the piano. My father didn’t play, but we had lots of records—Burl Ives, Leadbelly with the Golden Gate Quartet, Josh White, John Jacob Niles. My father knew John A. Lomax as part of the Texas intelligentsia; he was in between John’s age and that of his son, Alan Lomax. Alan came to the parties at my parents’ home. One time I remember Jimmie Driftwood and Pete Seeger were at the same party in my parents’ living room. That sort of made it good for Janet and me, to make connections and scope out what was happening in that whole scene.” Mayne remembers when he first got the idea to play the guitar himself, when he was about seven or eight: “It was when we were in Pasadena; my family was sharing a house with another literary scholar named Fred Bracher. He played guitar and sang cowboy songs. He was the first person I ever saw who played the guitar. I also remember an old man living near us who was an ex-cowboy—he built me a rocking horse. I was called ‘Tex’ in school because I had a Texas accent from when we lived in Austin.”

When the family was living in Minneapolis they had a housecleaning lady, a devout Episcopalian, who got Mayne singing in the boys’ choir when he was around ten or eleven. “It was my first paid gig. I had vocal training and some in compostion and I really learned a love of singing. My parents had me singing songs for guests at cocktail parties and stuff. In the seventh grade I played guitar and sang between acts of Huckleberry Finn; that was my first gig as a folksinger. Gene Bluestein, a graduate student of my father’s, also taught me some folk guitar and got me into an Almanac Singers-type group at a community center. We did the People’s Songbook repertoire. He and Pete Seeger were the first people I saw play the five-string banjo.” By the time Mayne was twelve he realized he was a natural at harmony singing.

The Smith family’s last move was to Berkeley, in 1953, when Henry Nash Smith became professor of English and administrator of the Mark Twain papers at U.C. Berkeley. He is perhaps best known for his work with Twain’s writings and now Mayne’s youngest sister Harriet has become editor of Mark Twain’s Letters, Vol. II: 1867-1868 (eds. Harriet Elinor Smith, Richard Bucci; U.C. Press, Berkeley, 1990).

“In Berkeley, I met Neil Rosenberg at Garfield Junior High. Our families were friendly; his parents, Jess and Mitzi, always liked to sing Christmas carols at our house. Neil and I started to play guitars and sing together. We followed Woody Guthrie and Cisco Houston, Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry and Leadbelly. We were both fourteen years old.” The two ended up spending a lot of time together even as roommates in college and for a long time they pursued similar goals in scholarship as well as music. Neil says that they must have seemed so alike to people that he was sometimes asked, “Hi, Mayne, how’s Neil?”

Mayne: “As we began to get driving licenses and cars, there began the first parties in Redwood Canyon at the Thomas cabin. Neil played guitar, I mostly flatpicked the banjo, Scott became a hot flatpicking guitarist and David Jones played piano and clarinet. David was a powerful and talented musician who really legitimized our music; now he’s a known player in the flamenco guitar world, under a different name.” So although Mayne is best remembered by Redwood Canyon Ramblers’ fans as the singer and guitarist, he actually was a banjo picker before Neil was. “I was listening to Obray Ramsay, Aunt Samantha Bumgarner and Harry and Jeanie West. I began to find some stuff that completely put Pete Seeger in the shade as far as I was concerned, as far as banjo playing was concerned.”

Mayne is also emphatic about the influence of blues on his music: “I have a pretty clear memory of the first time I took an E Chord on the guitar and put a finger behind it to make a barre and moved it up to play it as an A chord and then a B chord—to play a blues progression that way. The blues is like a solvent. It’s like a musical solvent that’s behind and part of everything I’ve ever done musically … a common base that everyone can understand. The home groove for jamming is the blues; it’s common to jazz, pop and Euro-and Afro-American folk styles. You can move from New Orleans through Memphis to Detriot and New York and Nashville, anywhere, using the blues to play together. When we started playing together it was something you could all jam on—everybody knew what the next chord was going to be; you didn’t have to worry about that. So that was the core of what we were trying to do, before we thought in terms of country music. ‘Mama Don’t Allow’ was an early standard and Leadbelly’s ‘Titanic’ and ‘Cotton Fields Back Home.’ Neil and I were going in the folksong direction, but the blues was the vehicle that gave us all something to play together. I think it was directly parallel to the skiffle movement in the British Isles, which we weren’t aware of. The founders of English rock and roll were going through what we were going through up there in Canyon.”

By 1956, Mayne was making frequent appearances on a live radio program on KPFA called the Midnight Special, both with and without Neil. The program was created in May of that year by Barry Olivier, local folksong enthusiast and founder of the Berkeley Folk Festivals and brought together countless performers weekly during its 11:00 to past-midnight time slot. Among them were all of the eventual Ramblers and some young bluegrass pickers following in their footsteps, most of the Canyon cast of characters, plus a folk roster too long to mention properly: Rolf Cahn, Mike Wernham, Dave Fredrickson, Miriam Stafford, Ken Spiker, Sandy Paton, Billy Faier, Merritt Herring, Toni Brown, Dave Ricker, Jesse Fuller, Janet Smith. Singers or groups would perform one after another and people were invited to come by the studio as a live audience. You never knew who you’d hear on the show. Players from all over the Bay Area—even Jerry Garcia in Palo Alto—would tune in the show or come by to play. It was a great melting pot of music, kind of like a big folk party being broadcast from Berkeley. The show was later taken over by Gert Chiarito. Always looking for new ways to present folksong sessions and ‘hoots,’ Olivier began hosting shows at a north campus restaurant called Cooper’s Northgate and Mayne recalls performing there the summer after high school graduation (1957) as “a Pete Seeger clone, mostly.”

But in the fall, Mayne and Neil left Berkeley for Oberlin College and immediately became immersed in the very active folk scene there. “A neighbor in my dormitory had a Roy Acuff record and I learned ‘Precious Jewel,’ almost for a joke. But then I gradually got offended at people for laughing at it.” He heard the new Folkways album release of the time, “American Banjo—Scruggs Style,” (FA 2314, 1956), and he heard Flatt and Scruggs records for the first time. “When Neil and I first went back to Oberlin together, I guess I thought of myself as being like Pete Seeger in front of an audience—playing the banjo, for the most part and singing songs that everybody could join in on. Being successful meant getting people to sing along, sort of being the catalyst for a creative, participatory musical experience. But eventually I began to discontinue the songleading bit. I just began to have a false feeling about it.” On a visit to Antioch College in Yellow Springs he was exposed to some “hard bluegrass” through Jeremy Foster and Alice Gerrard. “We were scoring Stanley Brothers as hard as we could. There was a ‘soul’ present there. There was a power and a lonesomeness and an authenticity in the sound of the Stanley Brothers and there was plenty of blues tonality there. And I soaked up a lot about harmony singing from them. However, I don’t think we were expressing that very fully in our own music at the time.

“A pivotal experience in my bluegrass development was hearing Bill Monroe’s “I Saw The Light” album (Decca DL 8769, 1958) with Edd Mayfield playing guitar. I didn’t know he was playing with a thumbpick, but I knew I liked what I heard and the guitar is very well recorded on there. I haven’t listened to that album for years and years but I can hear it in my mind very easily. I know a lot of the songs and I know where all the guitar licks are.” For someone who hasn’t concentrated strictly on bluegrass music since the heydey of the Redwood Canyon Ramblers to have such a clear memory of that sound thirty years later, those early impressions must have been strong indeed.

Mayne and Neil spent their 1958 summer vacation back in Berkeley and what Mayne calls “the first incarnation of the Redwood Canyon Ramblers” began to perform around town, although he’s not sure they were using the name quite yet. “We were actually more like folkies trying to play a little bluegrass,” he explains. At this point Mayne was still the banjo player. Neil played guitar and by this time Scott had gotten into playing the mandolin.

Back at Oberlin in the fall, both Neil and Mayne were members of the Lorain County String Band, a forerunner of the Plum Creek Boys. (See BU, December, 1986) But when Mayne returned to Berkeley for the 1959 summer break, he decided not to return to Oberlin. In the fall he enrolled at U.C.’s English literature department. So the summer of ’59 saw “the second incarnation of the Ramblers, the serious one.” The reason it was serious was because they—especially Neil—had been hearing professional bands back east, often on WWVA, WCKY (Wayne Raney) and WSM radio shows and they were charged up about the sound and the performance style of those entertainers. At the Washington School concert the following year, not only did these college kids wear hats, white shirts and string ties, but they also had stage routines incorporating their bass player as a comedian in the traditional bluegrass manner of the ’40s and ’50s. And they balanced their playlist, which drew from bluegrass and country recording artists as well as their own extensive knowledge of folksong and ballad sources, with novelty songs and ditties.

In some ways their approach resembled and was influenced by the New Lost City Ramblers, a trio of their peers on the East Coast who were performing old-time string band music at about the same time during the folk revival. But not in every way.

“While the New Lost City Ramblers seemed to avoid a sense of ‘show’ we were not afraid of being commercial,” observes Mayne. “We wanted to be authentic. They were deliberately regressive and we were not, although we did prefer ’40s-style Stetsons to cowboy hats. By this time Bill Monroe and the other acts had changed to cowboy hats, so we were imitating the bluegrass look of the recent past. We didn’t want to have the western image, yet we wanted to be honest, with a sense of the present day. Both bands were, in effect, paying homage to the performers they were emulating. The New Lost City Ramblers did in fact have an element of ‘show,’ although it was based on old-time acts rather than bluegrass.” (Neil still has his ’40s-style Stetson, but adds that he got a western hat in Wyoming on the way to Berkeley with Frank Miller in June of 1960: “I wanted nothing more than to look like Walter Hensley did backstage at Carnegie Hall the year before” [see John Cohen’s photo after pg. 202, Bluegrass: A History, University of Illinois Press, Urbana, 1985].)

Playing bluegrass in Berkeley at that time wasn’t the easiest thing in the world to do. For one thing, the folksong atmosphere created largely by the work of Barry Olivier, with its emphasis on quiet ballads, understated delivery and solo or duet singers, wasn’t entirely compatible with the powerful bluegrass sound even in trio form. And, too, this was the West Coast. Most people had never heard this kind of music before. Bluegrass came to the area through the folk music revival, not a country music context; the audiences were folk audiences. Mayne: “I remember fantasizing that someday the word ‘bluegrass’ would become common knowlege. It was awkward—it was hard to figure out how to describe what it was we were doing. It did have a cultural status, people were applying a label to it, but we had to educate people about the music in order to get them to come and see us.”

There were a few people around the area who the Ramblers didn’t have to educate, however. One was Arkansas native Roosevelt Watson, a devoted bluegrass listener who had about every bluegrass record ever made. He’d also seen Bill Monroe with Jimmy Martin in the ’50s, even leaving work whenever he could to drive to a personal appearance advertised on the radio. Roosevelt came to play a big role in encouraging people in their pursuit of the true music, especially Scott Hambly. Another was Campbell Coe, phenomenal guitarist, record collector, instrument repairman and salt-of-the- earth raconteur whose legendary status in the Bay Area once inspired an anonymously-produced Day-Glo bumper sticker reading, “Campbell Coe Is A Myth.” Fifteen or twenty years the senior of the Ramblers members, Campbell did his fair share of educating people about bluegrass and country music. In his best AM-radio baritone he delivered an excellent synopsis of bluegrass in his introduction to the Washington School concert. But for the most part, the Ramblers were playing bluegrass in a vacuum. Few national acts were coming out West, although in the winter of ’59 Monroe played at the Dream Bowl, a country dance hall just north of Berkeley on the Napa-Vallejo Highway and Mayne Smith was in the audience. It was his first live bluegrass by anyone other than his college and folk-revival peers. Campbell, who was tapped into the local country music scene, liked to encourage the city pickers to see shows at places like the Dream Bowl, often taking them there himself and of course Roosevelt Watson was a step ahead of everyone: he knew exactly what it meant to be playing music on the road, far from home and he and his wife arranged for Bill Monroe to come to their house to rest and eat. Roosevelt still has photos of Bill, Bessie, Bobby Hicks, Jack Cooke and Robert Lee Pennington sitting around their house.

What Mayne calls “the big summer of the Redwood Canyon Ramblers”—1960—was a big time indeed for them and for music in the Bay Area. It included the influential August concert at Washington School and numerous other shows, club dates, private parties and radio broadcasts, marking their most active season.

Around Berkeley, where the only folk guitar shop had been Barry Olivier’s convivial little place, the Barrel and the only instrument repairman was Campbell Coe (operating from his apartment near the campus until he opened Campus Music in the former Barrel storefront), a new guitar shop was opened by Jon and Deirdre Lundberg on April 15, 1960. The Lundbergs, expert in old-time music and the instruments to go with it, arrived in Berkeley from Omaha one day and drove straight to the Barrel. The Oliviers took them home for dinner and Barry found them their shop on Dwight Way, which recently closed its doors on November 30, 1990. Lundberg’s Fretted Instruments, so named because they carried no fiddles, soon became the happening spot for folk individuals to congregate, find old instruments and generally drive the proprietors crazy with the inevitable cacophony of guitar and banjo licks. Like Campbell Coe, who worked with the Lundbergs for a time, Jon had an incredible amount of detailed information about vintage instruments, Martin and Gibson specifically, educating countless beginners with his expertise and selling or trading instruments to many players. Mayne Smith had never played a Dobro before, but in later years he became proficient on it as well as pedal steel guitar: “Jon Lundberg had a Dobro he wanted to sell; he probably realized he might develop a market for such things if he got one into the hands of a working musician. Neil had crowded me out of the banjo slot and while I like flatpicking rhythm guitar and singing lead, I also liked to back people up. I like to be a sideman and the Dobro looked like a way for me to do that. I liked the early Acuff sound and I really liked what Buck Graves was doing with Flatt and Scruggs, so it didn’t take a whole lot of coaxing to get me into playing the Dobro. Jon figured out a way to make it economically feasible for me to own his Dobro and I never looked back.” But in the fall, with his stormy first marriage to Audrey Biscay (older sister of Neil’s Berkeley High girlfriend and part of the Redwood Canyon crowd) on the rocks, Mayne took off with $50 in his pocket to hitchhike east and reassess the relationship and his Dobro and suitcase were stolen on the road. “I realized I was in the midst of my rite of passage into adulthood. I hitchhiked from Fort Smith to Tulsa to Oklahoma City, saved up some cash washing dishes in a diner, visited family members in Dallas, then hitched back home in time for Christmas.” So when Mayne sings his riveting version of Harlan Howard’s “Busted,” made famous by Ray Charles, you get the idea he knows what the man was talking about. These stories also suit my impressions of Mayne at the time. He was long and lanky, like Hank Williams and his wife’s name was Audrey. Mayne and Audrey even sang country duets together, like Hank and Audrey Williams did. It was always tempting to look for country music models in our own community of musical denizens and sometimes easy: I always thought Campbell Coe looked like a young Jimmie Skinner and he could play like Chet Atkins. Toni Brown sounded like Kitty Wells but didn’t look like her. Vern Williams looked like a lot of rugged mountain men and his singing was an Ozark version of Bill Monroe and Ralph Stanley at the same time.

Mayne was out of school during 1961, he and Pete Berg were playing a fair amount of music together and the two of them roomed together in a place on north Shattuck Avenue. “I was playing small gigs and teaching music for bread. At the Blind Lemon bar down on San Pablo Avenue I’d make $10 and all the beer I could drink, one night a week. Somewhere in there we had a Redwood Canyon Ramblers trio, with me, Pete and Scott. We played on the Berkeley campus and at San Jose State.” A number of folk musicians were coming to town from the East Coast at this time—Jim Kweskin, Marc Silber, Perry Lederman, Pete Stampfel, Toni Brown, Buzzy Marten, Bobby Neuwirth—and a very active music party scene was going on in Berkeley with people such as Miriam Stafford, Pete Berg, Carl Dukatz (who was doing guitar repair with Lundberg) and country blues stylist T.A. (Steve) Talbot. It was said that Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee came around to some of the parties. But bluegrass didn’t go over that well in the party scene and Neil, who had graduated from Oberlin and started in the folklore program at Indiana University in Bloomington, was writing letters to Mayne about seeing Bill Monroe and other bands at Monroe’s Brown County Jamboree barn in Bean Blossom. Mayne really wanted to play music for a living, but that seemed impossible in Berkeley then. He’d graduated from U.C. and I.U. looked like a way to avoid the draft by staying in school. Mayne decided to apply and was accepted into the folklore program at Indiana headed by the late Richard M. Dorson.

“I went to Bloomington in 1962 and tuned in on Bean Blossom. I joined Neil’s group, the Pigeon Hill Boys, on guitar and played other local country and coffeehouse gigs both with Neil and as a solo.” But at school, a conflict turned up. On the one hand, it was a “coup” for Dorson to have the son of Henry Nash Smith in his folklore program; Dorson had been a younger student in the American Civilization program at Harvard when Henry was a graduate there, thought of Mayne’s father as a star and wanted to be on his good side. On the other hand, Henry Nash Smith’s son happened to be a folksinger and musician and that didn’t set too well with Dorson, who saw folklore strictly as a serious academic discipline. Music was linked to popularization, which he detested and folk music scholars were outside the mainstream of serious folklore research as far as he was concerned. “Dorson coined the term ‘fakelore,’ ” says Mayne. “He rejected almost everything that was done in the area of music, certainly in terms of performance. This all came under the heading of fakelore, including the folksong compendiums of Botkin and Lomax. This was also one way you could get funding from the government—if you could call your study a ‘hard discipline,’ or science.” Fortunately for Mayne, another scholar at I.U., an ethnomusicologist in the anthropology department named Alan P. Merriam, encouraged him to follow his instincts. “It seemed self-evident that there was a strong and vital link between bluegrass music and folklore. Actually I stressed in my theseis that bluegrass has an intimate relationship with traditional music but that it is a commercial form. I wanted to point out to all these people who kept calling bluegrass ‘folk music’ that there was something else going on here.” I recall Mayne saying that the microphone makes bluegrass commercial—that it was nearly as important to a bluegrass performance as one of the instruments.

Like Neil and Scott, Mayne has made significant contributions to the scholarly knowledge about bluegrass. His master thesis, Bluegrass Music And Musicians: An Introductory Study Of A Musical Style In Its Cultural Context (MA, Folklore, Indiana University, 1964), was the first serious study of the music and his “An Introduction To Bluegrass,” published in the Journal Of American Folklore in 1965, was the first article on bluegrass in a scholarly journal [and later reprinted in Bluegrass Unlimited during its first year],

“But I had to escape the stifling scene at Indiana,” recalls Mayne and he found himself transferring to U.C.L.A. to begin work on a Ph.D. with the late D.K. Wilgus. “Wilgus was a legitimized scholar who recognized the importance and value of what scholars call ‘hillbilly’ music. It’s ironic that the word ‘hillbilly’ was used in the scholarly world; it was the only place where it was a legitimate term. Bill Monroe and I think a lot of country musicians were turned off by the word. We were aware of its pejorative connotations, but our use of it as a jargon term came from Charles Seeger, I think, who distinguished ‘citybillies’ from ‘hillbillies’ in an article I read very carefully and critiqued. He might have coined the word ‘citybilly’ and he was using both words in a totally unpejorative fashion.” Still, using the word ‘hillbilly’ later got him into trouble with Bill Monroe, at the first Roanoke bluegrass festival in 1965. He had given Carlton Haney a copy of his paper to show Monroe, who turned a cold shoulder when he saw the term.

Later, Mayne wrote an insightful report on that first festival, based on his notes, published in Sing Out! in January, 1966 (‘‘First Bluegrass Festival Honors Bill Monroe,” Vol. 15, No. 6). He carefully describes Carlton Haney’s near-religious belief in Monroe as sole creator of the music: “ ‘Other groups have the beat, but Bill is the only man that has the true time and the only man you can learn it from so that people will pay to hear it.’ ” Mayne also took the occasion to adjust some of his earlier contentions, based on conversations with Monroe at Roanoke, telling Sing Out’s folk-music readership: ‘‘Although in the popular mind bluegrass banjo playing is one of the outstanding features of bluegrass music, to Haney it is the rhythmic features of the music which make it a unique style. And talks with Monroe make it clear that the refinement of Snuffy Jenkins’s three-finger banjo style by Don Reno and Earl Scruggs, the development of the tense, high-pitched singing style, the melodic kinship of bluegrass fiddle and mandolin with the blues—all these elements are subordinate in Bill’s mind to the beat and time of bluegrass.”

Eventually Mayne made the decision to leave school and the scholarly world. ‘‘Academia had begun to feel increasingly parasitic to me. I decided not to become a critic/musicologist; I wanted to do rather than to analyze so much. I was on the brink of a lovely career, like the career Neil’s had, but I began to feel it wouldn’t be authentic for me to do that. I love the immediacy, the joy, the thrill that comes from performing. Nothing in the academic world was as powerful for me. So I left school and started doing music, although I had also begun to realize that I wasn’t really a bluegrass musician. I realized I had a talent for writing songs, but I didn’t want to write bluegrass songs. I wanted to make a unique contribution.”

Before leaving U.C.L.A., Mayne worked at McCabe’s guitar shop and got involved in the L.A. music scene. From 1964 to ’66 he was sound man at the Ash Grove folk club, running the sound for virtually every gig the Kentucky Colonels had there during that period. He developed a friendly relationship with them and it is Mayne’s voice introducing them over the house P.A. on side two of their live collection on Briar (now Sierra) Records, “Livin’ In The Past” (BT-7202, 1975). For a short time he played bluegrass with Richard Greene and David Lindley, but concentrated heavily on songwriting. Mayne produced a demo tape of twelve of his original compositions featuring backup instrumentalists such as Ry Cooder, Clarence White, Richard Green, Bill Keith and Taj Mahal. Nineteen of his songs have been recorded by various artists; “The New Hard Times,” co-written with Bobby Kimmel, was recorded by Linda Ronstadt on the album that marked her breakaway as a solo star (“The Stone Poneys Evergreen Vol. 2,” Capitol T-2763, 1967). Rosalie Sorrels, Michael Murphey, Guy Carawan, Larry Croce and sister Janet Smith have also recorded his songs. (One of Janet’s songs, in turn, has been recorded by Doc Watson.)

While still living in L.A., Mayne began a continuing friendship and musical association with singer-guitarist Mitch Greenhill, son of Boston folk impresario Manny Greenhill [long-time manager of Doc Watson] and this started Mayne’s career playing rock-influenced electric music. He’d been a James Burton fan for years and credits the country guitar wizard as a critical influence on his Dobro playing. “He played some great stuff on a record I had in college, Glen Campbell’s ‘K-E-N-T-U-C-K-Y.’ It so happened that Nick Venet, producer of that record as well as the Stone Poneys, later did one for the country-rock group Hearts and Flowers and I played Dobro on a session for them.” Playing Dobro gave Mayne a chance to do plenty of backup work and take a break from the lead vocalist/rhythm guitarist/front man role he’d been in for so long. He picked up a fair amount of session work around the L.A. studios in those early days of the acoustic-country-folk-rock amalgam scene and has recorded Dobro, steel, guitar, banjo and vocals on eighteen releases over a 24-year period. This makes him the most-recorded of all the Redwood Canyon Ramblers, although never in a bluegrass context.

At McCabe’s Mayne learned some guitar repair and refinished his 1952 Martin D-18 that he’d bought from some friends of Neil’s, Miles and Joan Gibbons, in Columbus, Ohio. He also made a new pickguard for it that is sort of a Mayne Smith trademark. Hideo Kamimoto, respected luthier, told Mayne that he always remembered him by the unusual shape of his pickguard. “The guitar had some top damage that I wanted to cover,” Mayne relates. “I always liked the oversize pickguards that country singers such as Jim Eanes and Lester Flatt had, but I didn’t want to copy the usual shape. So I designed my own shape, which pays homage to a certain part of the anatomy of my girlfriend at the time. That pickguard is authentic.” As Neil Rosenberg said, quoting from Bill Monroe during an interview about the background on some song lyrics, “That has a story, but it don’t need to be told.” For a family magazine, enough has probably been said about Mayne’s pickguard.

Although it was difficult for him to give up the idea of making music as a full-time living, that is exactly what Mayne started thinking about after moving back to the Bay Area and his home ground in 1969. But there was still music to be made. He and Mitch Greenhill picked up where they had left off in L.A. and did a two-week tour with singer-songwriter Mark Spoelstra. They formed the country-rock group The Frontier Constabulary, later called the Frontier, which played gigs as both an acoustic and an electric band.

There was a second marriage that ended but did produce Mayne’s son Noah, now a dedicated guitarist at twenty and a fairly intense period in which he worked the commercial country and western circuit as a steel player around northern California and the Pacific Northwest. “I got a good take on the life of a travelling musician by working with a country band out of Seattle for a year and a half. I enjoyed playing for dances and developed my chops a lot, but I didn’t feel I was making any great contribution to people. I gradually burned out on the superficiality and constant travel. Also, I didn’t have the kind of talent to make it to the level of say, Buddy Emmons.” At this point Mayne really wanted to be a father, to have a reliable income and a stable home life for the first time in years. “I was tired of the night owl existence and I spent entirely too much time waiting for the telephone to ring for gigs. It was real hard, but I just let go of it. I had pushed it as far as it could go.”

One of his songs, “Slave To A Six-String Guitar,” chronicles what he calls his low point, in the mid-’70s. Then he heard of a job opportunity at Hideo Kamimoto’s guitar and violin shop in Oakland and it turned out to be a good thing. He ended up working there from 1977 to 1983. “It felt like something worth putting my weight into and I learned a lot working for Hideo. It was productive, valuable and it felt positive. There was even a chance for some musical expression,” as the scene at Kamimoto’s was vital, with many musicians working there part-time, among them fiddlers Paul Shelasky and Jack Leiderman. At one point they had enough musicians working at the shop for a full bluegrass band. When Hideo’s business relocated to San Jose in 1982, he asked Mayne to continue, but after a year the commute was too much and Mayne and his wife Gail settled on a house in the Richmond Hills, near Berkeley.

Even though Mayne followed through on his decision to leave the world of academia and not look back, he has nevertheless written nearly a dozen papers on music including articles, reviews, and album liner notes. The “Chronology Of Country Music,” which is a unique six-page foldout chart (published in The Country Music Who’s Who, ed. Thurston Moore, Record World, New York, 1970, reprinted 1972), displayed his special skill at collating a tremendous amount of information in a practical and artistic package.

At present Mayne is applying his high standards and innovative skills in the computer industry with a Fortune 500 company, having already acquainted himself in earlier jobs with textbook editing, electronics manufacturing and international trading in music accessories. The difference is that now he produces his specially-designed charts and catalogs using the latest computer technology. He is president of the Berkeley Society for the Preservation of Traditional Music, which owns and operates the Freight & Salvage coffeehouse, one of the Bay Area’s most important alternative music venues. He still performs, with Mitch Greenhill and others and has lately been putting considerable energy into Redwood Canyon Ramblers reunions with the possibility of their touring in Japan.

Mayne stresses his partnership with Mitch, a true soul relationship that’s lasted over twenty years. He says that even if he were to go back on the road with another band, “playing with Mitch will always be my main expressive musical outlet. It is a real partnership.” Mitch and Mayne appear on the “Berkeley Farms” LP and they released an LP, “Storm Coming” (Bay 215, 1979) and a cassette, “Back Where We’ve Never Been” (Bennett House BHR 107, 1986). They’ve also done two European tours as well as countless club and festival dates on this continent.

It’s also been a treat to see him playing some bluegrass guitar and Dobro again, one night in particular at a 1990 bluegrass event at Black Owl Books in Berkeley. It may be that at one point bluegrass was “old hat to Mayne,” a statement made years ago by his old picking buddy Neil Rosenberg to explain why we didn’t get to hear Mayne sing much bluegrass anymore, but it’s a hat he can wear again with comfort and integrity. He can still ‘throw his head back and sing,’ as we once characterized him in Pete Seeger’s likeness and he does it with great affinity for and understanding of the American music traditions. What bandleader and High Country founder/mandolinist Butch Waller said about Mayne, referring to the old Redwood Canyon Ramblers’ days (Bluegrass Unlimited, September, 1985), is still true today: “Our socks were rolling up and down, you know. It was intense music. Mayne—he was into it. He could sing the high stuff.”

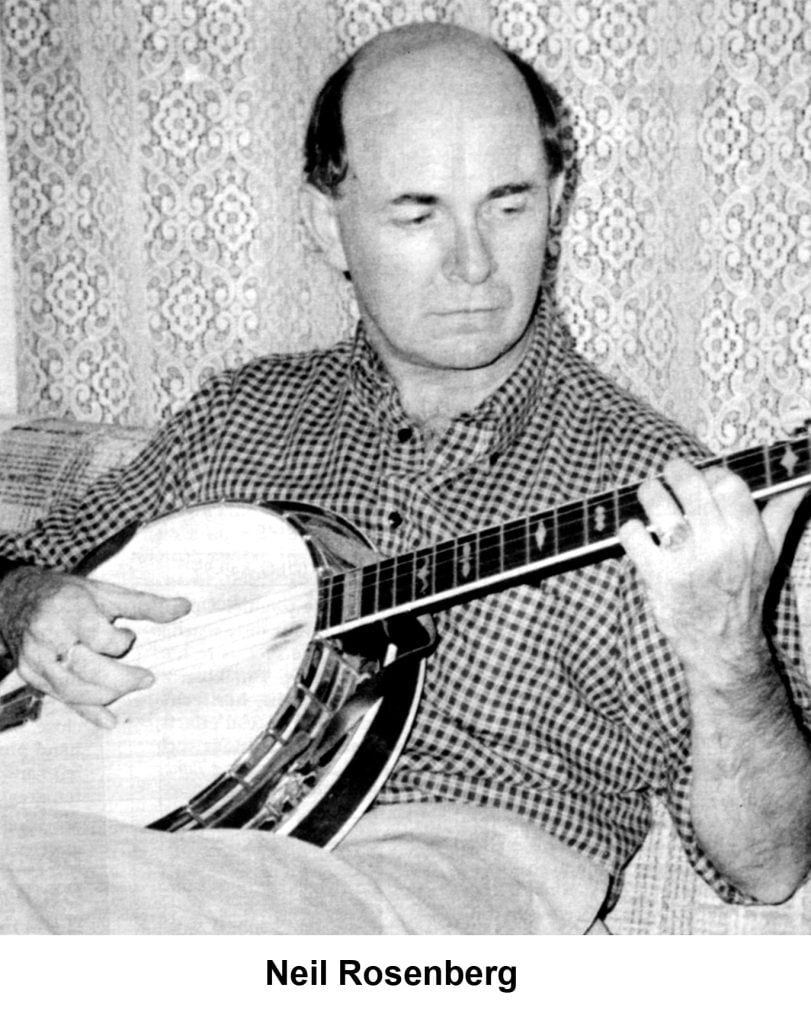

Next month—Neil Rosenberg

Redwood Canyon Ramblers — Part Two of Four

Written by Sandy Rothman

Part Two Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

June 1991, Volume 25, Number 12

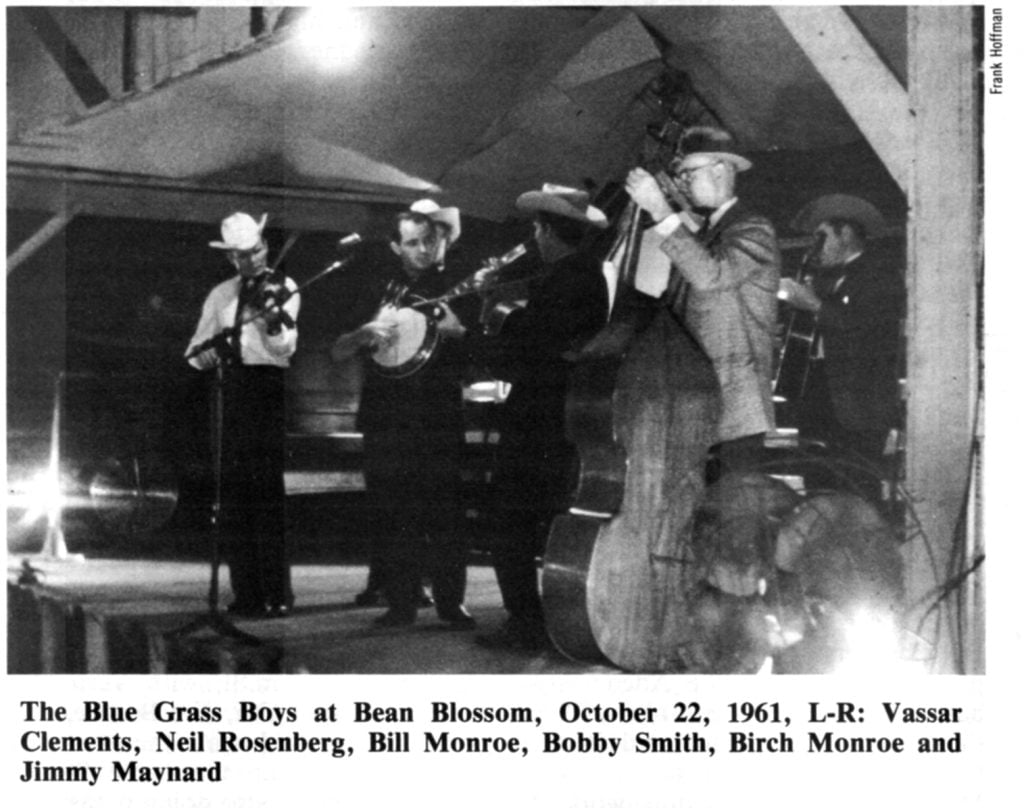

Readers of this magazine probably know Neil Rosenberg’s name primarily because of the monthly column he has written since 1980 called “Thirty Years Ago This Month,” if not because of his classic and lamentably out-of-print Monroe bible, Bill Monroe And His Blue Grass Boys: An Illustrated Discography (Country Music Foundation, Nashville, 1974) or his book generally regarded as the definitive history of the music, Bluegrass: A History. He has published over fifty essays in books and numerous articles in scholarly folklore journals, as well as more than thirty articles in popular magazines. He’s edited or written liner notes for more than twenty important bluegrass recordings on major labels, has presented papers at over fifty scholarly meetings since 1963, has given more than thirty public lectures, workshops, or seminars at such places as East Tennessee State University and the Earl Scruggs Music Celebration in North Carolina. And he even hosts a weekly bluegrass radio show, Bluegrass Country, over CKIX-FM in St. John’s Newfoundland, Canada, where he lives and teaches at the Memorial University of Newfoundland (initials M.U.N.) in St. John’s. In 1986 he received the Certificate of Merit from the International Bluegrass Music Association (IBMA), and in February, 1991, was voted Bluegrass Feature Writer of the Year for the third year in a row by the Society for the Preservation of Bluegrass Music of America (SPBGMA) at its national convention in Nashville.

The list of awards goes on and on . . . but what very few people know is that Neil is a fine banjo player and an accomplished multi-instrumentalist. He was a two-time winner (1963-1965) of the banjo contest at Bean Blossom, and he often played banjo with Bill Monroe and his Blue Grass Boys while working with the house band at the Brown County Jamboree during those years.

Neil Vandraegen Rosenberg was born on March 21, 1939, in Seattle and raised in the town of Olympia in Washington state. His father Jess earned his law degree at the University of Washington and served as Assistant Attorney General before moving the family to Los Alamos, New Mexico, in 1949 where he worked on the legal staff of the Atomic Energy Commission. In June of 1951, they finally moved to Berkeley when Jess took the position of General Counsel for the Western Highway Institute, a research foundation established by the trucking industry in the eleven western states.

His law specialty was interstate taxation and his major contribution was the development of the pro-rata license system used on the big rigs—those plates that you see with little squares for stickers from various states.

“My mother played the piano,” recalls Neil; “just fooled around with a few pop tunes now and then and could read well enough to play for party singalongs. My dad had an old Washburn guitar that he strung with just the top four strings and played like a uke. He’d sing camp songs, old pop tunes, party songs. I remember my parents singing ’20s and ’30s pop songs when we would be travelling in the car, often back and forth from Olympia to Seattle. I took violin lessons starting at age seven in Olympia and continuing on through Los Alamos and until I was fourteen in Berkeley. My first consciousness of folk music was through my father’s sister, Aunt Teya, who lived in Berkeley. She had records of sea chanteys and things like that, which my father also liked.” By this time Neil had also been playing the uke and fell in with some other kids at Garfield Junior High who played uke. “We were the ‘Flexi generation,’ riding those Flexible Flyers, predecessor to the modern skateboard, all over the Berkeley hills. We took our ukes with us camping and sang ‘Dan, Dan, The Lavatory Man’ and other tasteless stuff.”

Neil remembers when he first met Mayne Smith, shortly after the Smiths arrived in Berkeley in 1953. “I got invited to kind of an introduction get- together at the Smiths’, probably because of my musical interests and because we had some mutual friends. I remember not long after that, Mayne spent the night at our house and brought his guitar, a little mahogany Martin. He got me interested in moving from the uke to the guitar and I bugged my dad to let me put the bass strings on his guitar. Eventually I got to take the guitar to Aschow’s violin shop in Oakland and have it converted to six nylon strings.” This was long before any folk guitar shop appeared in the area; the friendly, violin-making Aschow brothers were always glad to help any budding musicians. “At about the same time I begged to be allowed to stop taking violin lessons and was told I could do so only if I promised to take guitar lessons. Through another friend at Garfield, a member of the Temple Beth El teen club that I belonged to, I found out about Laurie Campbell and her weekly children’s program on KPFA radio. This was in 1955. I took guitar and voice lessons from Laurie until she got married and moved to Chicago the following year.”

By this time Neil was getting together with Mayne plus Scott Hambly and some of his friends to jam. “We started going out to Canyon to wail and the infamous parties began to happen. We were influenced by Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly, the Weavers. Early on we made the big switch from nylon strings to steel string guitars. This was pretty revolutionary, because most people were still playing nylon string guitars.” Neil recalls going into the KPFA studios one afternoon with this group of friends and taping “our version of jazz, fifteen minutes of ‘St. Louis Blues,’ for a later broadcast.” Another time Mayne was invited to perform on the Midnight Special and he brought Neil along. “I had a successful audition with Barry,” says Neil, “and soon our scene moved into that setting and to other ones such as the Northgate hoots.”

A 1957 poster from Cooper’s Northgate restaurant reads, “Folk Song Jam Session, Fridays, 9 p.m., Coffee, Coke, Burgers, Pie, Root Beer—Euclid near Hearst, Berkeley—Everyone Welcome,” sounding just like a college campus in the ’50s. The happenings at Northgate got the attention of Oakland Tribune staff writer Morton Cathro, who surveyed the scene in a Parade magazine photo spread in the Sunday edition on October 10, 1957. Carrying the subhead, “Berkeley’s Modern Minstrels Spark Revival of Folk Singing in the Bay Area,” the report pictured Barry Olivier arriving with a lute in one hand and two guitar cases in the other.

Cathro asks Olivier to explain “the current upsurge” in folk singing. “ ‘Well, for one thing,’ says Barry, ‘it ties in with the do-it-yourself craze. A person who can count and keep time should be able to learn the guitar well enough to entertain themselves and maybe their friends. If a person sings well, he or she may make a good folk singer; if they don’t sing well, they’ll make an even better folk singer.’ . . . In a more serious vein, young Olivier feels there’s a deeper reason. ‘Psychologists say that one of the troubles of our society today is that young people feel no connection with the past. Folk music opens the door to a vast treasure of rich folk lore and give them a link to other times and other lands.’ ”

One of the “other lands” being introduced to a few of the local singers was, of course, the American Southeast—the land of bluegrass and old-time music. But as we’ve heard before, playing bluegrass in the Bay Area was not—is not—the easiest thing in the world to do. The campus folksong revival certainly helped to close the musical gap, but the home region of bluegrass is still a long way from California and for a variety of reasons any bluegrass roots the Bay Area has been able to nurture are still tender. If this is so today, to the early Redwood Canyon Ramblers it must have felt something like introducing a totally foreign botanical species to the New World. As Mayne said, they had to educate people everywhere they went just to get an audience. The bluegrass singing style is still fairly alien to the ears of Bay Area music listeners and so they center their attention on the instrumental side of the music; groups who don’t sing but still sound a little like bluegrass—David Grisman’s for example—more easily capture the local interest. But in the folk scene of the ’50s one problem was the loud banjo or sheer force of a bluegrass group in contrast to a solo folksinger or guitarist, so the parties in Canyon were not only a rural setting, they were also a place where Neil, Scott, Mayne, and their friends could pursue the music they wanted to play. “Canyon was the place for blasts,” says Neil. “I wrote a song around then called ‘That’s The Way A Blast Should Be.’ It was a safe place for us to congregate, drink, and carouse.” And play loud music, something you couldn’t do in the city or in the highly protective folk community. Neil: “In this sense, bluegrass was something of a rock and roll surrogate for us.” Bluegrass was as problematic for the folk scene as rock music was for the rest of the world.

At the beginning of 1957, Neil decided to go east, to Oberlin College in Ohio. “I wanted to go to Oberlin because it was a small liberal arts college with no fraternities or sororities, and because it had a reputation as being a place where there was a folk music scene. Also, Mayne had already applied and been accepted and he urged me to join him. We were roommates for the first year. Luckily our friendship still survived.” Neil majored in history, Mayne in English literature. “The folk crowd at Oberlin probably saw West Coasters as upstarts and I felt like a transplanted West Coast folkie.” But at Oberlin they began hearing and learning a lot about bluegrass. “Some of our classmates knew about bluegrass and also about Django Reinhardt and the Hot Club of France, which I got turned on to. Joe Hickerson had left Oberlin by then to study folklore at Indiana but former members of the Folksmiths, the group he’d helped lead (they made a Folkways LP), were still there and the folk scene was very active. “American Banjo—Scruggs Style” was just released, as well as the first Flatt and Scruggs Columbia and Mercury LPs. Everyone was trying to learn the banjo.”

Neil and Mayne took their first trip to New York during the 1958 spring break, meeting some of their East Coast counterparts in the city folk scene such as Eric Weissberg and Marshall Brickman. Neil credits Weissberg with showing him finger-style guitar and he still plays a lot of guitar, writing many original tunes as he does on the banjo. “Some of the East Coast musicians had a kind of chip-on-the-shoulder attitude,” remembers Neil, “but they were ahead of us musically. Alice Gerrard, Mike Seeger, and others were very helpful to us … I felt like we were following them. They also introduced us to the mystique of instruments and music.”

That summer, during what was to become their customary trip home to Berkeley during school vacation, Neil, Mayne, and Scott played together in a series of shows and KPFA radio appearances, and at summer’s end they went into Pacific Sound—a custom branch of radio station KRE that was run by Scott’s father—and produced a 12-inch acetate recording. Neil recalls making 36 hand-duplicated copies which they sold or gave to friends. Included were two bluegrass-style performances, “Little Maggie” and “Jesse James,” with Neil on guitar, Mayne on banjo, and Scott on mandolin.

While getting his B.A. in history at Oberlin, Neil began his bluegrass education in the Ohio environment. “I got to meet and play with genuine Carter County hill people from around Mansfield, the kind of people who would say ‘the banjo’s crippled up’ when the fifth string wouldn’t tune.” He and Mayne, with fiddler Frank Miller, played in the Lorain County String Band, precursor to the Plum Creek Boys, a band remembered by a lot of people around Oberlin in those years. (See “The Plum Creek Boys—College Bluegrass in the Early Sixties,” by Mark Schoenberg, M.D., Bluegrass Unlimited, December, 1986.) The Plum Creek Boys opened the show when the Osborne Brothers gave their first college concert at Antioch College in February of 1960. “Everyone was starting to know a lot more about bluegrass. I learned a lot by watching. I remember Benny Birchfield showed me the second break to ‘Earl’s Breakdown’ at the Antioch show.” Neil points out that Scott and Mayne had seen Bill Monroe in California, at the Dream Bowl, at just about the same time.

One of Neil’s first articles on bluegrass was a piece done in 1967 about these formative events of early 1960. Bluegrass Unlimited had recently begun publication, in 1966, and so Neil sent in “Bluegrass and Serendipity,” and it appeared in the November, 1967, issue (Volume 2, Number 5). He refers to a trip that he and some fellow Plum Creek Boys members took to WWVA’s World’s Original Jamboree radio show as per an invitation Bob Osborne gave onstage at the Antioch concert. “They announced the last act,” wrote Neil after describing the Osbornes’ brief set, “a name we were not too familiar with, being new to bluegrass, and out came what we thought was the funniest combination of physical types we’d ever seen. The guitarist and mandolinist were quite chubby; the fiddler tall and broad-shouldered; and the banjo picker was so skinny that it appeared his Mastertone might pull him down at any moment. We didn’t have time to laugh, for the moment they reached the mike the guitar player hit an E chord and the banjo player started playing the wildest single note stuff we had ever heard! Surprised? We were stunned—we’d never heard of Jimmy Martin or J.D. Crowe or Paul Williams or Johnny Dacus and we’d never heard ‘Hold Whatcha Got.’ ”

Fired up about bluegrass in a big way, the Redwood Canyon Ramblers really began to take shape when Neil came to Berkeley in the summer of ’59, and that’s when they got their name. “Scott named the band in nostalgic reference to our high school blasts at Canyon. At first Pete Berg played with us as second guitarist, then shifted to washtub bass because of the problems you tend to have with two guitars in a bluegrass band. Our first gig was at a little place on Telegraph Avenue called the Peppermint Stick, across the street from where Cody’s Books is now. Mayne got mononucleosis, so Pete went back to guitar and Campbell Coe got Betty Aycrigg to play string bass with us. We played Northgate and the Midnight Special in this same configuration.”

This marked the time when Neil became the full-time banjo player, when he was in town, and the banjo he used was a 1954 Mastertone with a skin head that he had on loan from banjoist Mike Wernham. At the end of the summer Wernham sold Neil the banjo, which he later upgraded by trading the pot assembly to Coe for a prewar shell. “Campbell was the first older person with direct knowledge and expertise about country music and instruments that I met,” Neil recalls. “Whenever you expressed enthusiasm about some aspect of the music, which for us meant bluegrass, he responded with some nugget of information that was guaranteed to be a conversation stopper. Sometimes they turned out to be tall tales. When I told him I couldn’t figure out how Scruggs was playing the guitar part on ‘God Loves His Children,’ he said it was because Earl was using a specially-constructed guitar with a five-string neck. In a sense the truthfulness of this didn’t matter. The important thing was his support of us and what we wanted to do. Like Gert Chiarito at KPFA, he was an understanding and enthusiastic adult.” In September Gert engineered a second demo tape for the band and then Neil went back to Oberlin—this time without Mayne, who had decided to stay in Berkeley. At Christmas break Neil and the Ramblers trio, without Pete or Betty, recorded four more numbers at KRE.

As Mayne mentioned earlier, the summer of 1960 was the heyday of the Ramblers. Neil and Frank Miller drove out from Ohio and with Scott and Mayne they reconstituted the band; Mayne recruited Tom Glass, an artist and jazz bassist originally from Columbus, Ohio, to round out the classic ensemble. They played gigs all over the Bay Area until the end of August—parties, radio shows, coffeehouses, benefits, and finally the crowning Washington School concert, where they had a chance to show an eager audience what they could do. Glass, the first Bay Area bluegrass bass player in a full band context, played the traditional role to the hilt, coached by the members who had been seeing the eastern bands. He straggled onstage, dressed as a comedian, and the band had comedy routines inspired by the Stanley Brothers. “This was before the Equal Rights Amendment for bass players,” Neil points out. “Earlier, the banjo player was a comedian, but Earl Scruggs changed that. Reno and Smiley solved the problem by everyone costuming, thereby singling no one out. The Kentucky Colonels did the same.

“Frank and I had summer jobs as housepainters and while we worked we listened to the live tapes we’d gotten from Pete Kuykendall and others. We really got into the ‘show’ aspect of the music—Frank especially did. I remember we played at Barry Olivier’s Continental Restaurant, a little coffeehouse northwest of the campus at Oxford and Berkeley Way and some of the New Lost City Ramblers came to see us one night. They commented that they didn’t do gospel songs or wear country-style outfits like we did.”

The Redwood Canyon Ramblers also started a trend for bluegrass in San Francisco’s North Beach, an old Italian neighborhood and local home of the Beat Generation. Clubs on Grant Avenue featured bluegrass all through the ’60s and ’70s, mixed in with the tourist crowds and jazz scene. Jack Dupen, plectrum banjoist and owner of the Red Garter dixieland club, liked the Ramblers and wanted to help promote them. “Jack had seen Monroe in the Bay Area in 1954,” relates Neil, “and he wanted to learn bluegrass banjo, but there was no one around to teach him. He got interested again after hearing us and took some lessons from me.” Dupen arranged an audition for them at the hungry i, the famous music and comedy club where Lenny Bruce was working, which was interesting because the New Lost City Ramblers had auditioned there earlier the same week. “[The NLCR] told us that the hungry i, people had been condescending, that they hadn’t even listened to a whole tune. This may have been because they didn’t see any commercial potential in them and maybe the band had little interest in the commercial aspect as well. Probably they were put off by the overt commercialism of the North Beach folk club scene. Although they didn’t want to allow themselves to become a ‘show,’ their dislike of it was ideological. They were in fact theatrical and liked for it.” In any event, the “other” bunch of Ramblers went over well with their string ties and their comedy routines such as the “Arkansas Traveler” [“How Far To Little Rock”] from the Stanley Brothers. “We didn’t get hired either, but we were well received,” remembers Neil. “Jack Dupen wanted to buy a club and make us the house band. He tried to talk us into going into music full-time. I often wonder what would have happened if we had decided to stay with it. We might have done really well.” Another friend and fan, Tim (“Rockin’ Rufus”) Doyle, also a Columbus, Ohio, native, had Redwood Canyon Ramblers business cards printed up with his name as manager and did what he could to promote the band. He even wrote letters published in the campus newspaper, the Daily Californian, when their writer said the Ramblers couldn’t be considered bluegrass because they were sometimes a trio. Rufus knew that even without a full band, these pickers played real bluegrass. But as fate had it, they all went back to school instead. Music was too risky.

Back east again, in June, 1961, Neil married Ann Milovsoroff and started graduate school in folklore at Indiana University. (Their two daughters, Teya and Lisa, now 28 and 26, live in Edmonton, Alberta, and Vancouver, B.C., respectively.) Frank Miller, best man at the wedding, started art school at Ohio State that winter and introduced Neil to Carl Fleischhauer and the vital Columbus bluegrass scene that included Sid Campbell and Robby Robinson. They hung out at Irv and Nell’s, the legendary Columbus bluegrass bar that later became Bob and Mabel’s, and heard a lot of great music. That’s when Neil got the idea to have Robby make a reproduction neck for his banjo, a neck he still plays on. The Bay Area folk scene and the Redwood Canyon Ramblers must have felt very far away to Neil as he was becoming part of a quite different culture. “I got into the midwestern mentality of bluegrass and I realized that places like Ohio and Indiana were much more the center than New York City. The local folkies at I.U. were less sophisticated than the ones on the West Coast, but a lot of them were interested in bluegrass and the bluegrass scene was miles ahead. Bloomington was a magnet.” Neil adds that some of these same people played dixieland, which he did for awhile too, and he also recorded Bob Dylan’s ‘‘Don’t Think Twice,” some years later in 1964, in a unique instrumental arrangement with the Rick Sutherlin Big Band. “It was a demo for a banjo and big band album that never happened. We played the arrangement in public at least once, at the Monroe County fair in Bloomington where the band worked as backup for the Buffalo Bills barbershop quartet.” Neil was playing a lot of Eddie Adcock-style banjo at this time—he’d always liked the Country Gentelmen and booked their first college date at Oberlin in May 1961—but his banjo work on “Don’t Think Twice” was pure Scruggs. “Sonny Osborne really turned me on too,” Neil acknowledges. I know this was true; Neil was into Sonny very heavily, encouraging me to learn “Cumberland Gap” the way Sonny was playing it at the time. Neil’s always been strong on emphasizing pure melody in his playing, a trait he credits to his father: “Dad was just like Earl Scruggs’s mother—he didn’t like for me to get away from the melody!” In late June of 1961, the Bloomington crowd encouraged Neil to go see Bill Monroe out at Bean Blossom, just about twenty miles from town. He tells the story in the Monroe discography: “My next door neighbor, a fan of old-timey country music, told me about a nearby country music park which Monroe owned and his brother Birch operated. On a beautiful Sunday evening in late June—the time of year that Bill now holds his festival—we drove out into the Brown County hills to Bean Blossom. No more than a half dozen cars were there at the Brown County Jamboree, even though it was 5:00, show time, and we wondered if Monroe would actually perform for such a small crowd. My neighbor and I approached a blonde woman standing next to an old Oldsmobile station wagon with Tennessee plates and asked her if Bill Monroe was really there. She assured us that he was, so we paid and went in.” There he met the late Shorty Sheehan (bass player on the classic Monroe session that had produced “Christmas Time’s A-Coming” and “The First Whippoorwill” a decade earlier) and his wife Juanita, musical Fixtures at the weekend jamboree. Neil says there were only about forty people in the audience in the old barn. Bill had Shorty playing fiddle, Bobby Smith on guitar, Bessie Lee Mauldin on string bass, and Tony Ellis playing a fancy double-resonator Paramount banjo with a skin head on it. “Shorty got me to play a tune on the banjo for Monroe and I played ‘Bury Me Beneath The Willow,’ probably an influence from Adcock and the Gentlemen. ‘That boy’s gonna be good if he keeps it up,’ said Monroe.” Neil didn’t forget that.

Shorty and Juanita constituted the Bean Blossom house band in 1961 and Neil played off and on with them there and at other gigs over the next seven years. In the fall of 1963, the Brown County Boys came together as the house band at the park, led by local fiddler Roger Smith, with Vern McQueen, Osby Smith, Jim Bessire, and Neil. They played again the season of 1965, then taking the name Stoney Lonesome Boys, also doing occasional gigs at other local venues.

Neil became quite close with the late Marvin Hedrick, a native of Brown County who collected bluegrass, played thumbpick guitar, and was a friend of Edd Mayfield’s. Hedrick once accepted an F-4 mandolin from Bill Monroe in trade for a sound system for the bam at Bean Blossom. He owned Hedrick Radio Service, a radio and RCA-authorized TV repair shop on the edge of Nashville, Indiana, the county seat, just about ten miles from Bean Blossom, and oftentimes in the evenings amid the clutter of TVs a friendly bunch would gather to pick. This could include Neil as well as the two Hedrick boys, Gary and David, who years earlier had been pressed into service for their dad, taping bluegrass radio shows for him in the early mornings before going to school. Many of these—sometimes dim broadcasts from faraway WRVA in Richmond, Virginia—as well as shows recorded by Hedrick live at Bean Blossom in the ’50s are in circulation among tape collectors.

It was the fall of 1961 when Neil played his first show with Monroe onstage at Bean Blossom, something that was repeated a number of times as Monroe often drove up from Nashville with less than a full band. “I was very nervous,” Neil remembers. “I kept asking what key the next song was going to be in. I think Bobby Smith gave me the wrong key intentionally one time. I didn’t have any time to decide what banjo tune to play and I blew a lot of breaks. I didn’t even know ‘Georgia Rose,’ which Bill said was a good number for the banjo. I remember apologizing to him after the show. He said, ‘That’s all right—you done the best you could.’ ” Neil also recalls how Monroe stood right next to him on the stage, emphasizing odd rhythms on the mandolin. He feels now as he did then that this was a kind of test to see how sure his sense of timing was. Neil’s banjo playing has always been rhythmically strong, so that wasn’t a problem. But he had concentrated on bands that featured the banjo more and he knew their material better. ‘‘Bill was a bit distant,” he says, ‘‘but not nasty in any way.” He adds, “There was no pay for playing the show.”

Neil also played banjo on two bluegrass recordings made in the Indiana area. One was an EP with Bryant Wilson and the Kentucky Ramblers (Adair 225, 1964) and the other was an LP called “Darkened Way” (Jewel 115, 1967) with George Brock and the Travelling Crusaders bluegrass gospel group. Neil thinks his banjo playing “didn’t really get cooking” until 1964, which is when “Don’t Think Twice” was done; in any case, his Scruggs intensity seemed to reach a peak in these years and if anyone can find these now-vintage recordings, the truth of this can be verified. During the period from 1967 to 1971, his playing “was propelled into a more experimental, personal space,” although—and this is something every banjo picker can relate to—Neil has never been one to let his chops stay down. As for his time in Indiana, he says, “I felt I had achieved something when someone came up to me at Bean Blossom and said, ‘The way you play “Bill Cheatham,” it sounds like a banjo.’ ”

Commemorating his days in Indiana and at Bean Blossom, Neil dedicated his book Bluegrass: A History respectfully “To the memory bluegrass bands got together in this way publicly, each drew its own audiences to the shows, creating more contacts. Eventually, these would lead to local bluegrass scenes which existed separate from both country music and the folk revival.” On the nonanalytic side, the show also presented an opportunity for Mayne’s driving guitar rhythm to match up to Ray Park’s sublime fiddling; very often Vern and Ray performed without a fiddle, as Ray could rarely find a strong enough rhythm player and usually had to do it himself.

This was also the year when Rick Shubb got to take a banjo lesson from Neil at Christmas, with me tagging along, and when Campbell Coe had the Ramblers play at some of the outdoor jam sessions he held in the alley near his shop. Campbell once had the Kentucky Colonels play there in the alley behind Telegraph and Haste; it was following Neil as Neil had followed him to Oberlin. Through 1964 the two of them played together in the Pigeon Hill Boys, which also included Chuck Crawford (now with the Toronto bluegrass band, Silverbirch), Fred Schmidt, Jim Neawedde, and Tom Hensley (now playing keyboards with Neil Diamond). There was a small flurry of Redwood Canyon Ramblers-related activity in the summer of 1963, when Neil and Mayne came to Berkeley and they did a gig at the Cabale coffeehouse where I played guitar and Mayne played Dobro; essentially, this was the final Ramblers performance. In February, 1964, Scott visited Bloomington from his Air Force base in Florida on a long weekend pass and the original band, assisted by Ann Rosenberg on bass, recorded seven songs for a demo. Neil recalls a few of the titles: “Childish Love,” a Louvin Brothers/Jim and Jesse number that Scott always loved; “I Ain’t Broke But I’m Badly Bent,” which Mayne learned from Edd Mayfield’s singing on a 1954 Monroe show recorded by Marvin Hedrick; “I’ll Walk Out On You,” an original Smith composition; “After Dark,” Scott’s version of a Kitty Wells recording that Red Allen had done in bluegrass style, and “Auld Lang Syne” as a banjo-mandolin instrumental. This was to be one of the last reunions of the Ramblers until they started getting together again nearly twenty years later.

For most of the 1963 season Neil managed Monroe’s jamboree at Bean Blossom. This was fraught with difficulties and if you get Neil started he can recall some pretty amazing stories from that period, such as the first show of the season when Bobby Helms came up from Nashville to play a show and drove his Cadillac into the back barn. But not everything was so funny. Bluegrass as a business seemed to be declining and it was all they could do to get new cement on the floor and things like that. Neil says that Marvin Hedrick helped him a lot; he calls Hedrick the “spiritual manager” of Bean Blossom. Working with Birch, who had been managing the park, could be difficult at times. Ralph Rinzler, Monroe’s booking agent, wanted to see Bean Blossom run a little tighter than Birch was doing it, so with Bessie Lee’s agreement he asked Neil to manage it. Bill was furious at first. He got in his car with the rest of the band and drove off to Nashville, leaving Bessie Lee to fend for herself. (This incident is described in detail by Jim Rooney in Baby, Let Me Follow You Down, Anchor Press/Doubleday, Garden City, New York, 1979). Eventually Bill came to accept and value Neil as manager. Working closely with Monroe this way certainly gave Neil unique insights into the mind of Monroe, the man, and it may be no accident that it’s been his lot to unravel some of the knots and tangles of bluegrass history.

I had been inspired by tantalizing letters from both Neil and Mayne while they were living in Bloomington—“just came from seeing (fill in the blanks: Bill Monroe, Reno and Smiley, the Stanley Brothers . . . ) out at Bean Blossom,” etc., etc.—so in the spring of 1964 I drove east with Jerry Garcia, banjo player in the band I was playing guitar in, so we could immerse ourselves in the real bluegrass scene. Neil and Ann were kind hosts to us and we also spent hours copying tapes from Marvin Hedrick, at Neil’s introduction. We did a lot of jamming with and without Neil around Bloomington, never quite mustering enough courage to ask Bill Monroe for a job in the band when we saw him at Bean Blossom. Neil also showed us the joys of an authentic bluegrass tavern in Ohio, taking us to see the Osborne Brothers at the White Sands in Dayton; for better and/or for worse, life for me has never been the same since.