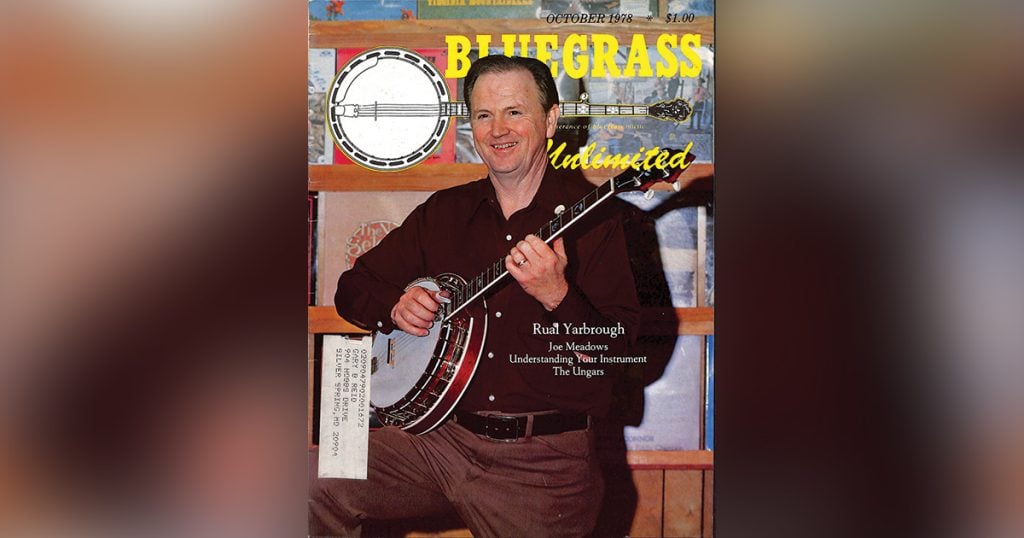

Home > Articles > The Archives > Rual Yarbrough

Rual Yarbrough

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

October 1978, Volume 13, Number 4

In 1967, in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, a barbershop closed. Now, ordinarily, the demise of a barbershop in the Recording Capital of the World, or anywhere, wouldn’t create much stir. But the closing of this particular establishment caused a collective sigh of relief from bluegrass musicians all over the country. It wasn’t that they were all getting terrible haircuts there. It was that the barber was joining them on a full-time basis.

When Rual Yarbrough opened that barbershop in 1956, he didn’t know how to pick a banjo. As a child growing up in Lawrenceburg, Tennessee, he’d listened to Bill Monroe on the radio and had big dreams, but music was something that happened for entertainment. It wasn’t something that put supper on the table.

“I play a little bit on all the string instruments. I really started out on bass years ago,” Rual recalls. “It was the first instrument I ever played. I tried the bass, the fiddle, and the mandolin. Guitar was the first instrument I ever tried to play. I never did accomplish much on any of them until I got to the banjo and put all the rest of it aside. I told myself that if I was ever going to get good enough to play with a group, I was going to have to get on one instrument and stay with it. I saw I wasn’t one of those naturals who could pick up anything and play it.

“Some people say you’re just born with a natural ability and maybe so, but I disagree to an extent. I was the type person who really didn’t have music about me. Didn’t anyone in my family play, but I wanted to play more, I guess, than anything in the world. I wanted to play so bad that I spent a lot of time and effort learning to play. It comes a lot easier for some people than it did for me. I feel like I wouldn’t have ever learned to play with a group had I not been so interested.

“I’d listen to guys on the radio at the opry and I’d try to figure out where they were playing on the instrument, what key they were playing in, so I really wanted to play. I see people now who can play, sounds like, as good as me and I’ve been playing 22 years and they’ve been playing roughly two! They learn it so easy.”

Now, Rual is a very modest fellow. But everyone else recognizes his ability and sings his praises. “Rual picks better and makes fewer mistakes than most modern musicians,” Jake Landers swears. “He can do ‘field’ music, and play behind singers. It’s hard to do. Besides that, he’s a terrific singer with one of the most beautiful tenor voices I’ve ever heard.”

Jake should know. He was one of the original “Country Gentlemen.” Rual, Jake, Hershel Sizemore, and occasionally, Vassar Clemments began to get bookings locally. They played radio and television stations all over North Alabama. As their bluegrass reputation grew, so did their national demand. But The Country Gentlemen discovered “their” reputation was more widespread than they’d realized.

“Occasionally on a road trip someone would say they’d heard one of our records on WCKY,” Rual laughs, “and I’d always tell them it wasn’t one of ours because we didn’t have any out.

“Then, on a trip through Virginia near Washington, I saw a billboard saying, ‘The Country Gentlemen’ were appearing. So then we knew there was another group by that name, and we had the sense to know we couldn’t pick up somebody else’s name and keep it if we were going any further with our music. We decided we’d change it to ‘The Dixie Gentlemen.’ That’s the name we used when we had the recording contract with United Artists.”

Besides United Artists, the group recorded for The Time Record Company out of New York, and did an album on the Dot label with Tommy Jackson. They recorded at Bradley Studio in Nashville which, at that time, was known to be the best.

“Well, I’ve accomplished what I’ve always wanted to do,” Hershel Sizemore said about that time, “I’ve recorded for a major label. I don’t know if I’ll have any interest to go any further or not.” So the deal with the Hubert Long Booking Agency never really materialized.

“We just kind of sat back with the music for six months or so,” Rual recalls. “We wanted to limit it to weekends, and no agency wants you just for weekends if they’ve got a demand seven days a week, so they never booked us the first date. It wasn’t good for my barbering business for me to leave it so much.

“We just kinda fooled around for a while and, like I say, picked a little local again. We were just going through times when first one and then another of the group would lose interest and it would kindly put a damper on it for awhile. That’s when I’d go to work for somebody else—when we were not doing very much ourselves.”

About 1966, Hershel moved to Roanoke, Virginia to work with the Shenandoah Cut-Ups, and Rual went to work with Jimmy Martin in Nashville. The next year found him in Utica, New York with Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs.

Before he could lay down his banjo and pick up his scissors, Rual got a call from Jim McReynolds. “I guess the night Jim called me and asked me to go work with them in Louisiana was one of the greatest thrills I ever had in music,” declares Rual. “Even through I’ve filled in for some great banjo pickers and worked for the Nashville Brass, Jim and Jesse have always been known to have top banjo pickers at all times.

“They had always been kind of my idols in the bluegrass field. I always really liked what they did. I will say that in the past few years I haven’t been as impressed with what they’ve done, but back at that time (1967) they had Allen Shelton with them—and of course, Vassar Clements was fiddling for them some—and they were just tops in my mind. I feel like it was a real honor just to be asked to help them.”

“One thing led to another,” Rual says, “And about 1968, I worked a year with Bobby Smith out of Nashville.”

“I was working with Bobby, really, when I got the job with Bill Monroe. We were working the WWVA Wheeling Jamboree twice a month. I don’t know why we were doing it. I’d go from here to Nashville and get with the guys (they called themselves The Boys from Shiloh, or The Shiloh Boys) and we’d go to Wheeling to work the Jamboree. Bobby said we’d get some dates—Wheeling’s a real strong station—up in there, even into Canada. That sounded real good, so we’d go. They paid us union scale, so it would about pay our way there and back plus motel.

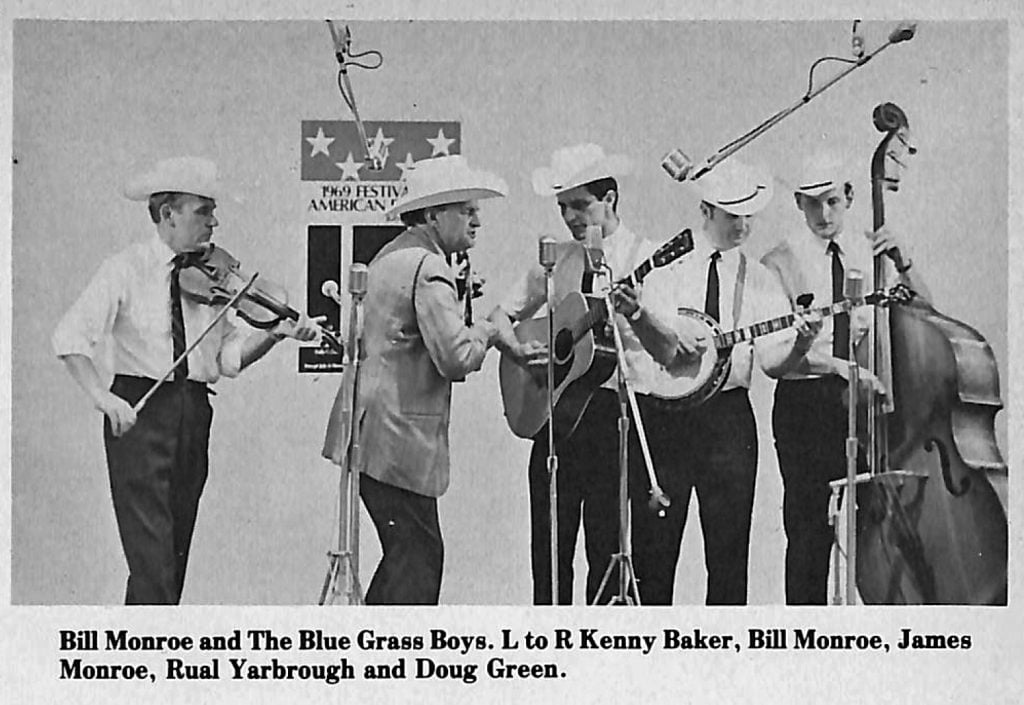

“This particular time we were on our way to Wheeling when we went through Columbus, Ohio. Bill Monroe was working a small club there, so we stopped over to visit with them a little while. Vic Jordan had just left Bill, and they had another boy from Springfield, Ohio filling in that night. I mentioned to Kenny Baker that I’d like to have the job. I had no idea they’d consider me because Vic was such a good banjo player I didn’t think I could take up anywhere close to where he left off.

“Kenny told me he thought I could get the job if I wanted it. So he went back to the dressing room and told Bill. Bill came out and talked to me and told me to call him on my way back from Wheeling on Monday. I did, got the job that Monday, and we went in for a recording session on Wednesday!

“Actually, that wasn’t the first time I’d worked for Bill. Back in 1963, Jake and I filled in a little bit for him. I wouldn’t call ourselves working for him regular. Back then he was at one of his low times, and he was picking up musicians every time he’d go out. Maybe they’d leave Nashville with three musicians and count on picking up the other two before they got to their date. We worked a few shows like that, and I even worked a week with him down in Louisiana on All Gospel.”

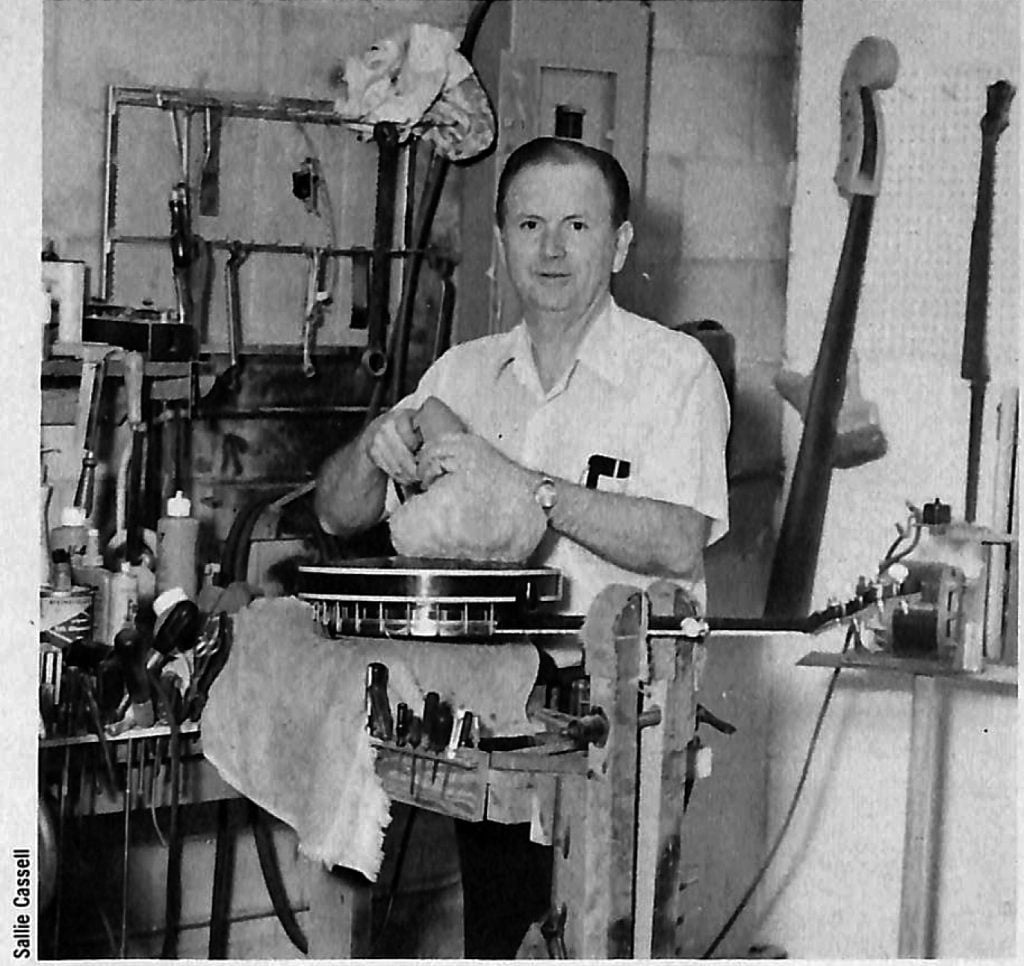

During his road tours, Rual became interested in the mechanics of the instruments, themselves. He would stop and visit with people who did repairs, and made a neck or two for a banjo.

“What I did at first was very crude,” Rual remembers. “It was done mostly at the house and not in a workshop, and with the bare essentials in the way of tools. I got to thinking that if I had a little shop and did repair work and some custom work, sold a few instruments, maybe I could make a living at it as well as barbering. So, in 1966, I tried it. I barbered on for roughly a year before I went into the music store full time.

“A little later, a guy from Georgia who really put us in the custom work joined me. I probably would never have gotten into the things I did if it hadn’t been for Randy Wood. He’s a real good craftsman. He’s a draftsman by trade which gives him a fine line and a good touch on everything. He really did some excellent work: custom inlay, carving, woodwork and engraving. He got the business started moving as far as that part of it.”

When Randy decided to strike out on his own at The Old Time Picking Parlor in Nashville, it was Rual who helped him get started.

Rual began to build a reputation among musicians for his repair and custom work. Not only bluegrass, but rock musicians started bringing their instruments to him. Members of both the Allman Brothers and Lynyrd Skynyrd bands have had work done. So has Hank Williams, Jr. who had his guitar repaired.

In the bluegrass field, his list of customers sounds like a roll call of The Hall Of Fame; Jim and Jesse, Jimmy Martin, Bill Monroe’s mandolin (“Randy took it home and slept with it.”), The Osborne Brothers, J.D. Crowe.

The six-string banjo he created for Sonny Osborne created such a stir, J.D. Crowe called him. “We’ve done quite a bit of work for J.D.,” Rual says. “Like I say, we also made him a six-string neck like we did for Sonny.

“We’ve just finished a neck for him now to go in a metal body Dobro-type thing with which he’s going to be doing some different sounds. Although he’s going to maintain a great portion of his show with real hard-driving bluegrass, I think in some of the clubs they’re going to try some new things. The neck we made for him is similar to a Fender guitar neck. We strung it up like a guitar in this metal body tri-cone which is an old National Dobro type thing. It was a four-string to begin with. He may have invented a new instrument. It’s quite a challenge to do something like that and make it work because you go from one type instrument to another….from a four-string to a six-string.”

Rual says that a guitar gives more trouble than any other instrument he has ever repaired. “It doesn’t seem like it would, but I guess due to the box being as big as it is, the bridge has always been pretty bad to pull up. Now they’ve got glues that are much better than they used to be, but we still have some of that to happen.

“And somebody who plays regular will wear the frets out on the neck over a period of time. Some guitars get warped necks and we wind up taking all the frets out and straightening the finger board.

“Of course, in banjos you don’t have the bridge (pulling up). The main work with them is the replacement of heads and frets.

“There are ways of taking care of instruments that makes the finish last a lot longer. It’s hard on a musical instrument, for example, to leave it in a car. Neither the trunk nor the inside of a car can protect an instrument from extreme weather. I know some guys who always take them into the motel room with them at night and that’s good. Both too hot and too cold weather causes a lot of changes in wood.

“Of course, keeping your instrument cleaned up and polished preserves the finish. A lot of people have a tendency to play it and just throw it in the case, and never wipe off the strings or finger board or neck. But you’ll get a lot of smoke and collection of film on it if you don’t clean it with the right thing. We use Gibson’s Spray Polish. We’ve had them come in with such a thick coat of film, that when we’d put the spray on, it’d just turn white.

“You could actually use furniture polish in some cases if the instrument was clean. Sometimes, though, furniture polish has a little too much oil in it and if there is an open place in the wood, it would get down into it.

“I’ve never had any trouble with wearing the finish off one. But that all depends on the type work you do. A lot of these guys that pick have a sideline of working on old cars or something like that. I’ve known a few who were brick masons, and they have rough hands and can wear the finish off in just a little while. The instrument needs to be refinished if it’s worn down to the bare wood, otherwise I don’t recommend it.

“I never had the problem. I don’t know that I ever kept any one banjo long enough to wear the finish off the neck.” Rual glances over his stock and then says, wistfully, “I wish I could keep all of them.”

Besides selling instruments, repairing them, and doing custom work, Rual is doing a little picking these days. He is often called by one of the local studios to put banjo on an album, and has done so for everyone from Swampdog to The Staple Singers. He even appeared in the film, “Stay Hungry.”

He fills in with the Nashville Brass whenever Curtis McPeake is unavailable. Now calling themselves, “The Dixiemen,” Rual’s group has nine recordings out with Old Homestead Records of Brighton, Michigan.

With more custom and repair work than he can keep up with, and bookings whenever he wants them, Rual has attained a comfortable easiness about his music. He’ll sit back with his banjo and a cup of coffee to look at bluegrass with the perspective of someone who has been in it long enough to watch it grow.

“Bluegrass has changed quite a bit since I started in it,” Rual recalls. “Fact of the business is, when I started playing there were not any electric instruments in bluegrass. I can remember a time, and some of the festivals ’til yet, almost just prohibit someone bringing an electric bass in.

“I don’t object to electric bass, but I like acoustic bass if someone can play it. Dan Glenn, for instance, does an excellent job, and he makes the bass do a lot of things you couldn’t do on an electric bass. You can’t play slap bass on an electric instrument.

“If someone can really play the upright bass, I think it can be played in any type band. If you were fighting other electric instruments turned up real loud, sometimes you might have to put a pick-up on it because you just don’t have the volume.

“I think bluegrass is just like country…you know, took a big rise a few years ago. Now, of course, country is here to stay but it had its low time. Bluegrass has done the same thing. 1962 was the beginning of Bill Monroe making a comeback. He was real strong back in the earlier days and he had some low times.

The future of bluegrass? “Well, I wouldn’t say bluegrass is dying out, but I think it’s headed for some things they’re going to have to keep a tight hold on to keep it from getting out of order. I see it happening at the festivals. They’re going to get some bad names like some of the rock festivals have.

“Of course, that doesn’t mean it’s going to hurt the overall sale of it on the market, but in the minds of a lot of people (real, staunch, bluegrass lovers) who see it as a good, clean, family entertainment, it’s changing for the worse. Drugs and that sort of thing.

“I find that festivals that haven’t been in existence very long are the cleanest and kept in the best order. Seems like after they go for awhile they begin to let things happen…allow people to get by with things they didn’t at first.”

And Rual himself? “To have accomplished as much as I have, I’d say God has blessed me an awful lot in my music and this store. Most every job I’ve ever had filling in for guys, or whatever, I never did feel like I was good enough to do it, but I happened to be the one available at the time. I’d say I’ve has some real opportunities.”

“Rual plays well, runs one of the few music stores that caters to bluegrass,” says Jake Landers, “and he never misrepresents any instrument he has for sale. But I’ll tell you what’s so great about Rual Yarbrough. What’s so great about him is the kind of man he is.”