Home > Articles > The Tradition > Remembering Sam Tidwell

Remembering Sam Tidwell

The music of the Country Gentlemen, J.D. Crowe and the New South, and the Tony Rice Unit will be familiar to even the most casual bluegrass music fan. Many would claim one or more of these bands as their all-time favorites. More hard-core bluegrass enthusiasts will also fondly remember shorter-lived, but equally as innovative, bands such as County Store, Spectrum, and Chesapeake. The one common element to all of these bands is bluegrass mandolin legend Jimmy Gaudreau. Gaudreau’s contribution to these groups were part of what brought them wide recognition and acclaim.

One of the distinctive aspects of Gaudreau’s musical background was that he did not grow up in the bluegrass-rich southern mountains. He was a native of Rhode Island—not generally considered a hot bed of bluegrass. So, how does a kid from Rhode Island become interested in playing bluegrass music? Musicians from many areas of the country where bluegrass is not prominent will typically have a mentor or a main influence that brings them in the door. The person who first influenced Jimmy Gaudreau was a guy named Sam Tidwell.

Jimmy explains, “There wasn’t much going on in Rhode Island bluegrass-wise until a guy named Bill Moody started putting on shows down near Wakefield, Rhode Island in a little village called Peace Dale. He got a hall and invited local acts to be the opening act and then he would feature this band called the Cedar Mountain Boys who were from up in the northwestern part of Rhode Island. Sam Tidwell was the banjo player and fiddle player in that band. They had a guitar player, a Dobro player, and Sam’s brother Bob played bass. It was the first really good sounding bluegrass band that I ever saw live. I had heard records, but I’d never seen live bluegrass sound that good.

“I got to know Sam because they would take a break and you’d get to talk to these guys. I said, ‘My name is Jimmy Gaudreau and I play a little mandolin.’ He said, ‘I play a little mandolin. Keep at it. There aren’t many mandolin players around this neck of the woods.’ That was my introduction to Sam and live bluegrass.”

Born August 11th, 1936, Warner H. Thibodeau, a.k.a. “Sam Tidwell,” was a Rhode Island native who joined the United States Air Force after high school. In the Air Force he was initially an Airborne radar specialist and later served as a bombardier and gunner on a B-26 during the Korean War. Returning to Rhode Island upon completion of his Air Force tour of duty, Sam earned an Associates’ Degree in Electrical Engineering while working full-time for Raytheon.

Tidwell’s father, William “Bill” H. Thibodeau, was a concert violinist for the Rhode Island Philharmonic Orchestra and taught his children how to play the piano and violin at a young age. However, as Bill aged, he started to lose his eyesight and could no longer read sheet music. Not wanting to give up his instrument, Bill transitioned from concert violinist to country fiddler. Sam learned how to play the guitar and back up his father at local country dances.

Sam’s introduction to bluegrass music came from a radio broadcast from WWVA in Wheeling, West Virginia. This is where he first heard the sound of a banjo and he was determined to learn how to play the instrument. He purchased a banjo and started to teach himself how to play. Not having a teacher, nor having ever seen a bluegrass banjo player, he developed a solid backward roll (1-3-2…thumb, middle, index), instead of the more prominent forward roll (3-2-1…thumb, index, middle). Luckily, soon after Sam started learning how to play the banjo he met another aspiring banjo player from New England named Bob French. Bob—from Acton, Massachusetts—had met Sonny Osborne and learned the correct Scrugg’s forward roll. French helped him learn the forward roll and Sam—literally—moved forward from there.

Once he developed some solid skills on the banjo, Sam began searching for other musicians who were interested in playing bluegrass music. When he could not find anyone who was familiar with bluegrass, he found people who were adept at playing various acoustic instruments and started converting them. Sam’s “converts” would include a young guitarist named Floyd Bradley who’d been playing country music and possessed a clear, natural tenor voice. He also found Ollie Steadman, who had learned to play Dobro from listening to early recordings of Roy Acuff featuring Pete Kirby (a.k.a. Bashful Brother Oswald), as well as Buck “Josh” Graves who had paved the way for Dobro in bluegrass when he became part of Flatt & Scruggs and the Foggy Mountain Boys. Additionally, Sam found that his younger brother Bob had an interest and a natural aptitude for bass, so Sam encouraged him to pursue that instrument. This quartet would become The Cedar Mountain Boys—one of the first bluegrass bands to be made up with personnel who were all New England natives.

Now immersed in the music, Sam decided to leave Raytheon and open a music store in Pascoag, Rhode Island. Sam bought and sold musical instruments, studied and mastered instrument repair, taught a variety of stringed instruments to students, and worked to find venues where his band could perform.

Eventually, Sam met a music promotor, Bill Moody—a displaced West Virginian—who loved bluegrass music. Moody began to promote shows at Patsy’s Music Hall in Peace Dale, Rhode Island. At these shows, Moody would have a group of local amateur musicians play a set and then have Tidwell’s Cedar Mountain Boys perform. This is where Jimmy Gaudreau saw his first live bluegrass and said, “That Cedar Mountain Boys performance would serve to influence my musical direction from that day on.”

In the mid-1960s, Tidwell moved to the town of Plainfield in eastern Connecticut and opened a music store with a talented multi-instrumentalist Fred Pike. They started to host jam sessions at the store and attracted bluegrass enthusiasts from all over New England. The store was only active for a short while as Sam received an offer to go on the road with Red Smiley in 1966. Not wanting to miss the opportunity to play with one of the legends of bluegrass, Sam moved his family to Troutville, Virginia and went on the road with Smiley’s group. When Tidwell left, Pike decided to close the music store and move to Maine. Unfortunately, Sam’s career as a traveling musician had to be terminated late in 1966 when his wife, Dorothy, became ill. The family moved back to the Northeast and, sadly, Dorothy passed in March of 1967 and left Sam to raise their five children.

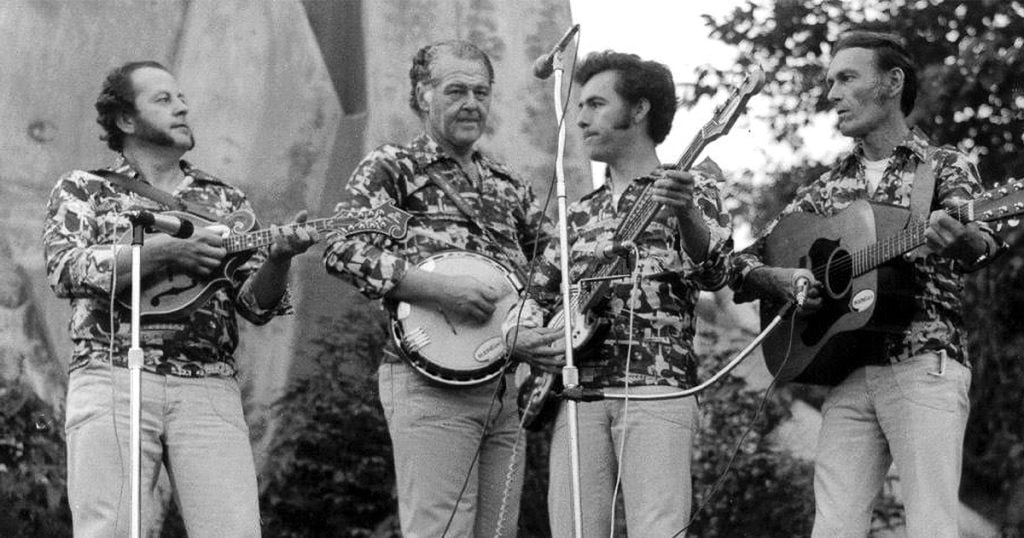

With his new focus necessarily on his family, Sam worked a variety of jobs and opened an antique store called The Trading Post. However, in 1969, Fred Pike called Tidwell and asked him to move up to Maine. The two would form a new bluegrass band called The Kennebec Valley Boys. During 1969 and 1970 they performed on a local TV show. The band swiftly gained notoriety and began booking gigs. Tidwell was back in the music business. The band performed, in various configurations, until the mid-1990s and was awarded the Best Bluegrass Band award by the Maine Country Music Association in 1975. Additionally, the Bluegrass Association of Maine recognized Sam Tidwell as a pioneer of bluegrass music.

During his years in Maine, Tidwell ran a small farm, taught math and science at a high school in Dexter, Maine, and repaired instruments. He also owned and operated a music store in Dexter called Strings & Things. In about 1976 the Kennebec Valley Boys started a bluegrass festival at the Yonder Hill Camp Ground in Skowhegan, Maine. That festival ran for several years. Then, Sam and his new wife Edie ran their own bluegrass festival for three years in the early 1980s at their farm. About that same time, Fred Pike started running his own festival—The Salty Dog Bluegrass Festival—which continued through the mid-1990s.

In addition to having performed with Red Smiley in 1966, Tidwell also spent a short time performing with Don Stover, in 1973, and Jud Strunk, in 1975. He also filled in with Don Reno and Mac Wiseman. Sam’s son, Billy Thibodeau—who currently plays mandolin with the band Rock Hearts—remembers, “Dad would play with anyone who came through. He was trying to make as much money as he could playing music. His first love was the banjo, but he could play any instrument. In the Kennebec Valley Boys he played mandolin because Fred Pike was such a good banjo player. I remember when Don Reno would come through, Reno would grab a guitar and invite Fred to play banjo for the whole show.”

In addition to being a talented musician, Sam Tidwell was also a songwriter. One of his songs “The Last Log Drive” was a true story song written about the last log drive (in 1976) on the Kennebec River. When the local news ran the story, they used a piece of Sam’s song as the background music. When that story ran, the national news picked it up. Having a piece of that song run on national news led to Good Morning America inviting the Kennebec Valley Boys to perform on the show.

After spending close to three decades in Maine, Sam and his second wife, Edie, decided to move to Florida, where Sam remain active in bluegrass. Billy Thibodeau remembers, “They started spending winters in Florida in about 1993 and decided to move there in 1996.” During his time in Florida, Tidwell performed in several bands, including The Prospectors and The Cypress Creek Band.

In the mid-2000s, Sam was chosen to be among the 250 “Pioneers of Bluegrass” that were interviewed for the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame and Museum Oral Histories Project. Sam and Edie were both interviewed for that project. In addition to this interview being viewable at the Bluegrass Hall of Fame and Museum’s Oral Histories Exhibit, it will also be a part of the oral history collection at the Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History at the University of Kentucky Libraries.

In 2007, Sam was diagnosed with inoperable cancer. He and his wife moved back to Rhode Island so that he could receive treatment at the VA hospital and be close to family. Although the cancer went away, Sam’s lungs were scarred and thus his breathing was impaired.

Sam Tidwell passed away a decade ago, in April of 2012. Sam and Edie, his wife of thirty-five years, raised eight children. In 2018 Sam Tidwell was inducted into the Rhode Island Bluegrass Alliance Hall of Fame. Sam was one of the true pioneers and heroes of bluegrass music in New England. Jimmy Gaudreau remembers, “In 2011, at the Joe Val Memorial Bluegrass Festival, I had the honor of presenting Sam with The Joe Val Heritage Award in recognition of his being considered a true New England Bluegrass pioneer. He would perform that day with his sons David, Marc and Bill along with friends, John Stey and Dave Orlomoski and this would be the last time he would perform on stage. And perform he did, despite his being in a wheelchair and the ever-present oxygen canister, he would proceed to play his unfaltering banjo breaks and entertain the crowd with his side-splitting ‘down east’ humor. Sam didn’t have to work at being funny, it came naturally.”