Home > Articles > The Archives > Stuart Duncan: Bluegrass In Miniature

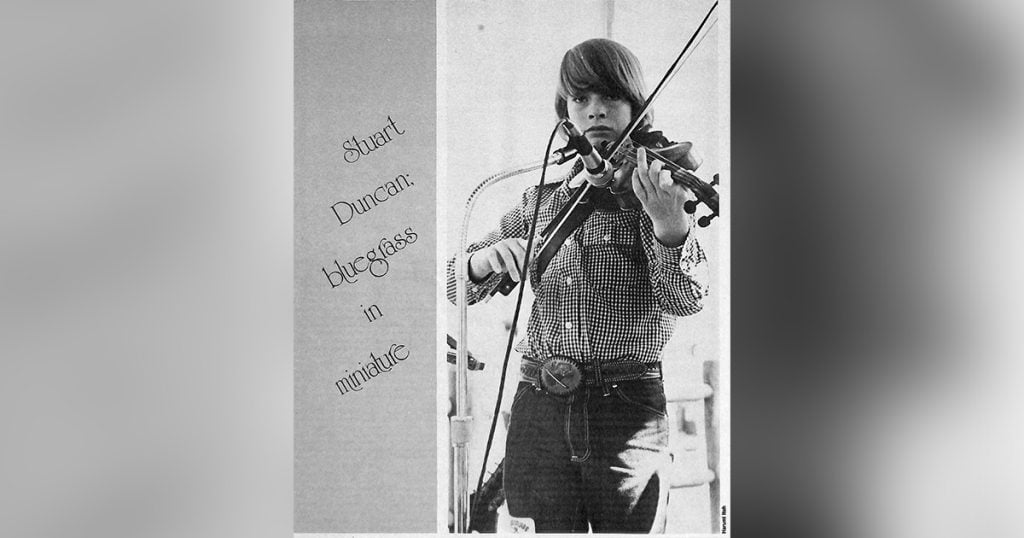

Stuart Duncan: Bluegrass In Miniature

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

November 1977, Volume 12, Number 5

There are many young pickers in bluegrass and traditional music; child prodigies are visible in every field of endeavor, not only music. What is unusual is a teenager who can do it all musically, handling virtually every traditional instrument as well as singing, arranging, songwriting and a growing share of the MC work—and well!

Another particular of Stuart Duncan that sets his career apart from those of other bluegrass youngsters is that, at thirteen, he is already a seasoned professional having appeared with; Marty Robbins, Tanya Tucker, Debbie Reynolds, Grandpa Jones, Bill Monroe, Roy Acuff, Lester Flatt, Emmylou Harris, and as sideman for; Mac Wiseman, Josh Graves, Eddie Adcock, Roger Sprung and others.

His musical career began “after watching Bill Cunningham play five straight sets on fiddle with Mason Williams, Kurt Boutourse, Pat Cloud and Aunt Dinah’s Quilting Party at a folk club in Escondido (California). I don’t remember much about it because I was only seven at the time, but I remember that it was good.”

His mother remembers: “We had all these instruments around the house and he kept banging on them. We told him if he wanted to play he should pick one and we’d get him lessons. This was right after he had seen Bill Cunningham: the only instrument we didn’t have was a fiddle.”

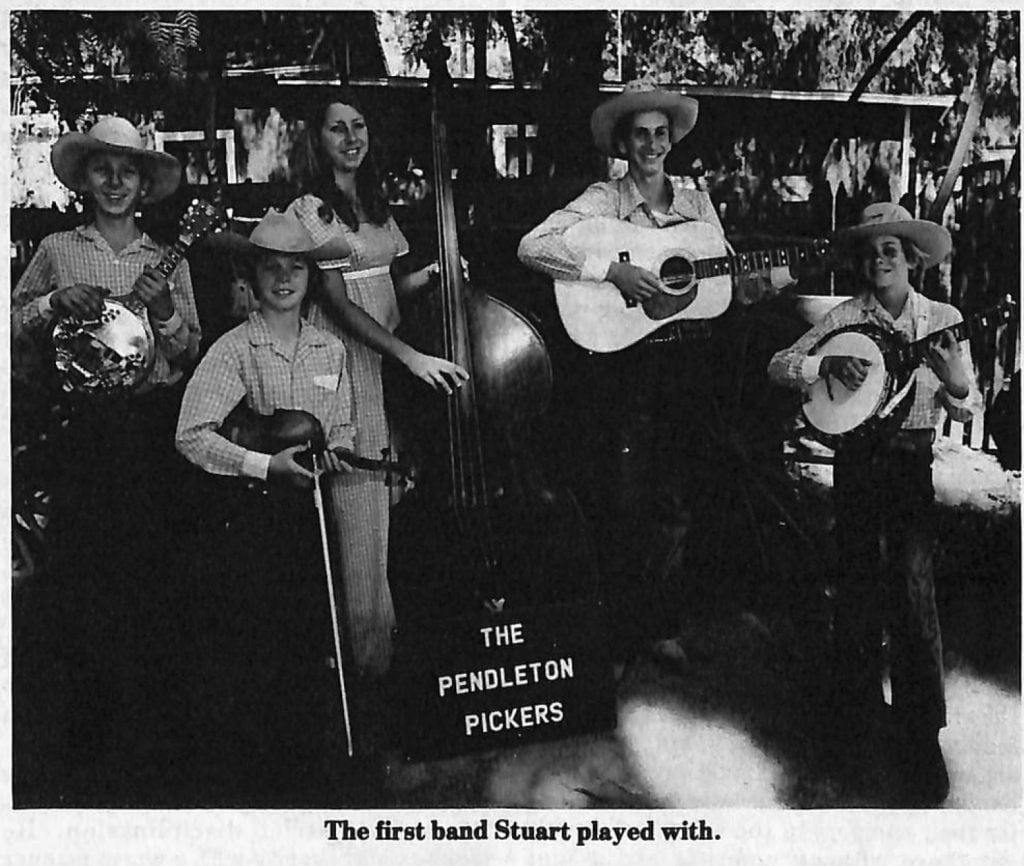

Brian Steeger, formerly of the Arkansas Shieks, was Stuart’s first teacher: “They hit it off pretty well,” says Stuart’s father. Apparently so, since within a year’s time the boy, with his father’s help, joined forces with four other youngsters in the North San Diego County area to form the Pendleton Pickers. The Pickers gained a reputation as a fine bluegrass band with little mention about their ages. It was during his two years with this group that Stuart began to demonstrate the versatility that sets him apart from his contemporaries. The Pickers already had a good mandolinist in John Moore, so Stuart watched, listened and learned. Eight-year-old Stuart got interested in the banjo and before long he and banjoist Steve Hady were playing duets on their own, and each other’s, instruments in the act.

Although Stuart was two years younger than the next-youngest Picker, he also was the group’s spokesman (“In case you’re wondering why I’m doing all the talking, these guys made me.”) but was not allowed to sing. This became an increasing frustration since he was beginning to come under the influence of singing bands like Country Gazette, The Seldom Scene, Ralph Stanley (“…especially with Keith Whitley.”) and the Country Gentlemen. Despite—or maybe because of—the restriction, Stuart began applying himself to this new musical challenge.

The apex of the Pendleton Pickers’ career came when they won San Diego radio station KSON’s 3rd annual “Country Star” contest, outscoring sixteen finalists. Part of their prize was an appearance on the Grand Ole Opry; Stuart was nine then. As the youngsters grew, their musical interests, and the intensity with which those interests were pursued became increasingly diverse and the Pendleton Pickers finally disbanded.

Emmett Duncan recalls: “Stuart decided that he didn’t want to join another kids’ band and there weren’t any adult bands that were quite ready to take him on.” Stuart went on his own for a while, “and”, according to Stuart, “I wasn’t what you’d call the most proficient musician at the time.”

But his father feels Stuart is too critical: “He had some rough edges, but he was doing all right. In the solo act I insisted that he practice and know what he was doing, whether talking or playing. He did everything else, though. He picked the songs and did the whole thing. In my opinion, he enjoyed playing in a band more because he didn’t have to do all that work. It’s really a combination of that and his having more fun in a band.”

Stuart Duncan’s first appearance as a member of an “adult band” came when he joined his neighbor, banjo maker Geoff Stelling in The Native Sons Of The Golden West. In the Native Sons, Stuart’s desire to sing was encouraged by the band’s lead singer and mandolinist, Bob Jones. “Bob knows more bluegrass songs than anyone I’ve ever seen,” says the boy, who considers the Sons the best local band he’s worked with—other than his current band.

At age eleven, Stuart enrolled in Lou Curtiss’ three-unit course on bluegrass and folk music at the University of California at San Diego. The boy was accompanied by his father, who received an “A” for the course, and was justly proud of himself—until he saw Stuart’s “A+”.

During this period Stuart, again with his father’s encouragement, became intrigued with the fiddle music of his Scottish ancestors. The summer of 1975 saw the Duncans in Scotland and the following year at Alexandria, Virginia Stuart won the National Junior Scottish Fiddling Championship.

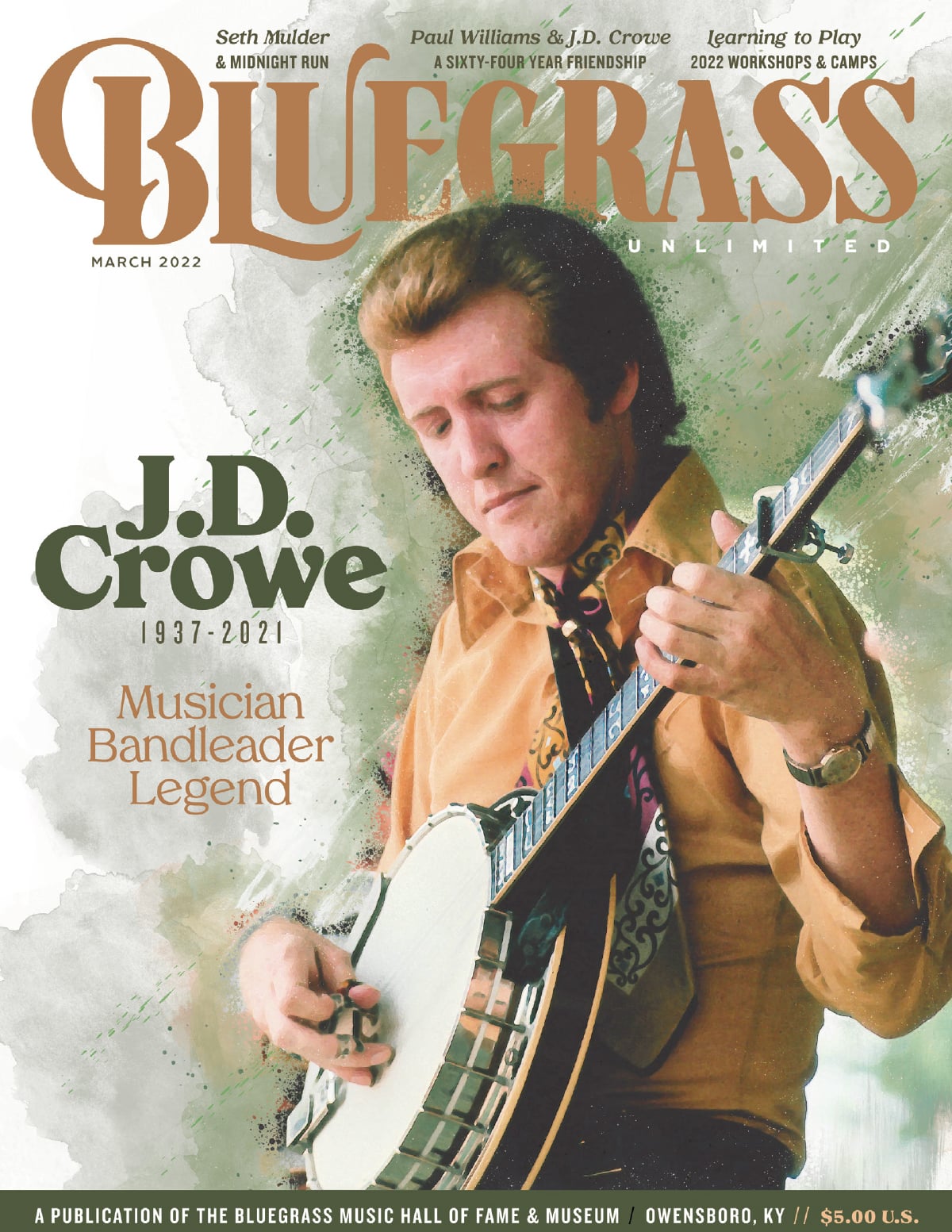

The summer of ’76 saw the Duncan family on the bluegrass festival circuit and a startling musical development in the boy. Twelve-year-old Stuart not only jammed and sat in with many big-name bluegrass bands but spent hours at a time parked in front of festival stages, tape deck in hand, intensely studying musical and stage mannerisms of his musical heroes, most notably J.D. Crowe’s New South.

“He had a very crestfallen look on his face when he found out—too late—that J.D. Crowe wanted to see him after he had played. By the time we found out, Crowe had left.”

Emmett continues: “He works hard in his own way. At Wise, Virginia he was at the stage for twelve hours, with his father feeding him. I’d say, ‘Hey, kid, you want something to eat?’ and he’d say, ‘Get me a hamburger.’ Everyone else was running for their campers in the rain but he’s still out there with an umbrella and a tape recorder. At the Berkshire festival he was out even after the power went out; it wasn’t till after the lightning that he finally quit. He came back with a lot of new licks, though.”

Stuart brought back even more: Experiences like playing Chubby Wise’s fiddle with the Shenandoah Cutups, rare concert tapes and Kenny Baker’s old fiddle, and a headful of ideas for a new band.

Upon returning to Southern California, Stuart got together with Duncan family friend Larry Bulaich and festival promoter Dick Tyner forming Pain in the Grass. The band had soon outpicked forty-five other professional and semi-professional bands from all over Southern California in open auditions for Magic Mountain amusement park’s house bluegrass band in a new section of the Valencia park called Spillikin Corners, the gig to run from May to September (*See End Note). Dick quit to pursue festival promotion full-time and was replaced by banjo wizard John Hickman and Magic Mountain asked for a new name. They are now called The Gold Rush.

This November 17th The New Mickey Mouse Club will provide Stuart Duncan’s first national television exposure. On the show the boy does the complete act with banjo, fiddle, mandolin and guitar.

“He also plays for a Mousketeer square-dance number. He wanted to play hard bluegrass, but there wasn’t any way with the ‘uptown’ backup band,” recalls Emmett.

“They had, among other things, a cowbell. At one point during “Rawhide,” the drummer hit that thing: Stuart had never worked with a cowbell, and thought he’d broken a string. He kept playing, though.”

One should assume from the foregoing that the parents of a child such as Stuart Duncan must be energetic, knowledgeable and, above all, patient. Emmett and Kristin Duncan are this and more.

Kristin Duncan is a planner for the City of Santa Paula, California, where the family now resides. Her father was a professional musician for twenty-one years, including six years in the Paramount Studios Orchestra, and has composed orchestration for “Macbeth” and an original cello concerto, among other works. Although quite busy with her job, she still “plays guitar and sings a little,” according to her son.

Emmett is a retired Marine Ordnance Captain, frailing banjoist, musical perfectionist and strict disciplinarian. He tempers his severity with a warm manner and great sense of humor. Since his retirement he has been honing his considerable skills at instrument repair. Emmett built his son’s first Dobro with a Chevrolet hubcap and converted tarpaulin snaps into instrument snaps. Recently, the Duncans acquired Sneaky Pete (Kleinow’s) old pedal steel guitar and Emmett is now in the process of retuning (which is tantamount to rebuilding) the instrument for less exotic applications.

Emmett’s sense of music and staging was well developed at the formation of the Pendleton Pickers, but he’s seen a lot since then. He has often been less frustrated by his son’s antics than by those of some of the “grown-ups” around him. “Going back over the contests he’s won and lost—and Stuart’s a pretty good judge of judges—he’s often come to me at the end of a contest he’s won and said that the judges were dead wrong and that so-and-so should have won. Many times youngsters win because they’re cute and can play almost as well as the big guys, but there are also judges that make up their minds that no matter how cute he is forget it, and their minds are closed no matter how well he plays. As for band jobs, I can say the same thing, just change ‘judges’ to ‘promoters’. Plus child labor laws in California are so tight and widely interpreted from local commissioner to local commissioner, that some promoters consider it more trouble than it’s worth. To me, it’s no more advantageous to be a good musician at twelve than at twenty-five.”

While The Gold Rush perform six shows daily at Magic Mountain, Emmett shops local newspapers for bargains on instruments, works with the park’s sound crew and entertainment directors, fields offers for night work and beams with pride when his son puts on his usual brilliant show.

At present, Stuart’s favorite instrument is fiddle, with mandolin running a close second. Most of his musical heroes are mandolinists or singers: Ricky Skaggs, Tony Rice, David Grisman, Vassar Clements, John Duffey and Keith Whitley. At this point he is confining his pedal steel playing to around the house. “That’s just something to do instead of skateboarding or watching TV. I enjoy the sound of the pedal steel and the qualities of certain pickers I like. About half the fiddle licks I play are pedal steel licks, so I figured I’d learn where they came from and learn the instrument—or at least fool around with it and try.”

Stuart explains his approach to a band: “At first when I didn’t know my fiddle, I didn’t have time to listen to what was going on around me—I had to figure out what I was doing! Now I can handle a fiddle pretty well and I can concentrate on what’s going on around me.

“I love to listen to the overall band sound, but now when I know that something doesn’t sound right in the band I feel pretty helpless because I can’t correct it. Besides, there is always some opposition to children telling the adults what to do.

“I like a banjo player like J.D. Crowe, he’s not really flashy, but he sure punches a song and puts life in it. I think that’s ninety percent of the banjo player’s job. John Hickman plays like that. He plays a lot of fancy stuff, but he still keeps that hard, going, motion thing that adds so much to a band.”

Stuart’s latest musical endeavors have been in the area of writing, at this point mostly rewrites of traditional songs, such as “Schoolboy Blues” (an adaptation of “Muleskinner Blues”).

“It’s more my dad’s idea. With the kind of voice I have now that hasn’t got the right sound in it yet. I can only do the novelty songs, it’s the only stuff I can make sound good. If I do serious bluegrass it doesn’t sound good with my voice unless I’m singing harmony. I haven’t written anything serious yet—a few tunes, but no vocals.”

Stuart Duncan has a bright future in music, but neither he nor his family are waiting a day for it. “If Stuart wants to hang it up,” says his father, “I won’t argue with him—it’ll be a lot easier for me! But as long as he wants to pick, I’ll help out all I can.”

*Note: In what he called “a moral issue”, L.A. labor commissioner Francis Bacon withheld a work permit for the Magic Mountain job forcing a court fight which finally resulted in Stuart getting his permit, but only after M.M. replaced Gold Rush with Hot Off The Press. Gold Rush will be working at the Mountain weekends this winter.