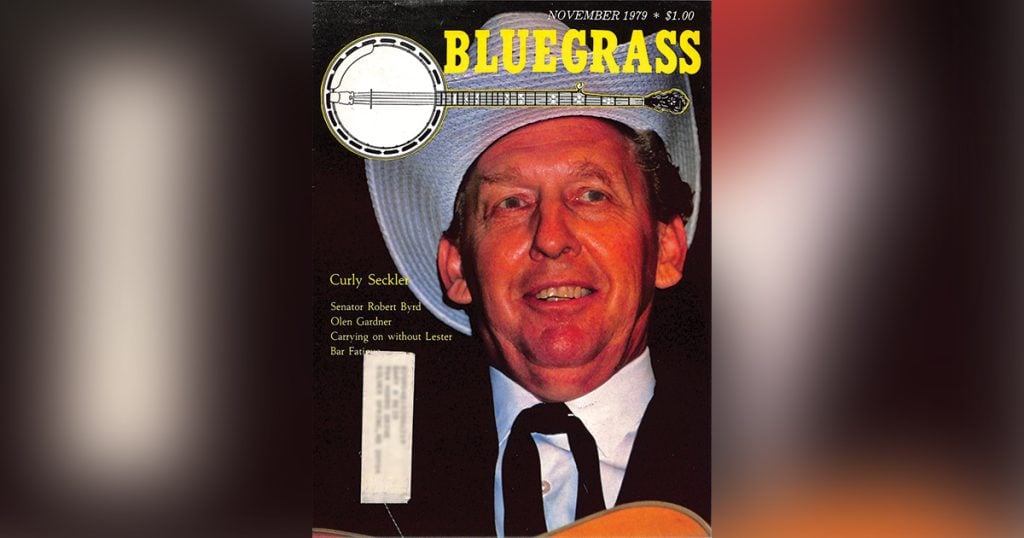

Home > Articles > The Archives > Curly Seckler — From Foggy Mountain to Nashville Grass

Curly Seckler — From Foggy Mountain to Nashville Grass

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

November 1979, Volume 14, Number 5

EDITOR’S NOTE: As the right hand man off and on with the late Lester Flatt, Curly Seckler has been one of the true unsung heros of bluegrass music. His roots go back to the mid 1930’s and he has been a strong force in the shaping of the music. This interview and story was done while Lester was still with us and now, as was Lester’s request, the band that Lester had fronted through the years is known as Curly Seckler and The Nashville Grass. Though a eulogy to Lester by Curly might be in order, it is obvious that Curly paid his respects to his boss and friend through the years in the supreme way—while Lester was still living.

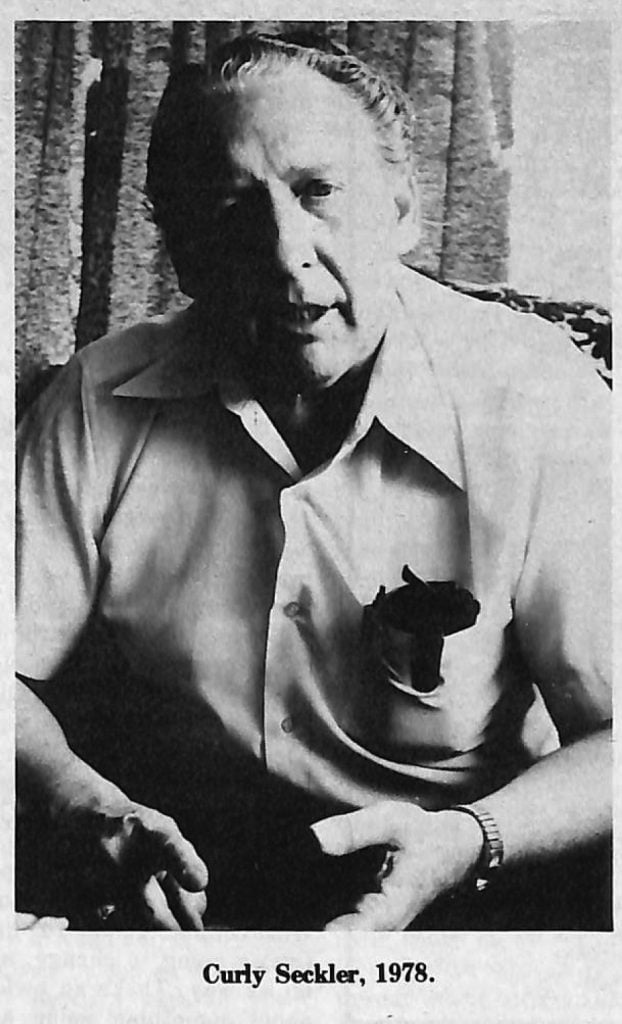

A talk with John Ray “Curly” Seckler is like a guided tour through the heyday of hillbilly music from a man who, in an over forty-year professional career, has seen it all.

Curly is youthful, articulate and maintaining a schedule with The Nashville Grass which would exhaust many men half his age. His voice is also seemingly ageless, virtually as strong and clear as it was on the classic recordings of the Foggy Mountain Boys, and even his earliest memories are equally clear.

“I was born and raised on a farm down in North Carolina, in China Grove. My father died when I was nine years old, but he was a great tenor singer, according to my mother. He sang in churches and played the autoharp. He had a couple of autoharps there at the place and, of course, the kids growing up got hold of them and tore the strings all off after he passed away. My mother played guitar, and she bought me my first guitar when I was about ten years old. I can remember sitting on the floor, listening to her pick the guitar and showing me G and D chords, and what she taught me then is all I’ve ever learned on the guitar. My brother was a good fiddler and one time I started to try to learn the fiddle, and I played it so loud the mosquitoes left. I never heard such a racket in my life as I was doing with the fiddle, so I finally laid that down and took up the banjo with a man named Happy Trexler. We’d walk about two miles to get to his house, and he was a fiddler. I’d take the five-string and beat some old drop-thumb stuff, which I never was good at, but back then I could get by with it.

“We couldn’t afford cases for our instruments, so my mother made these old red sacks with zippers across the tops of them. We’d put the instruments in them and put them across our backs and we’d walk down there, two miles or so, and play. I was probably fourteen years old then, or fifteen.

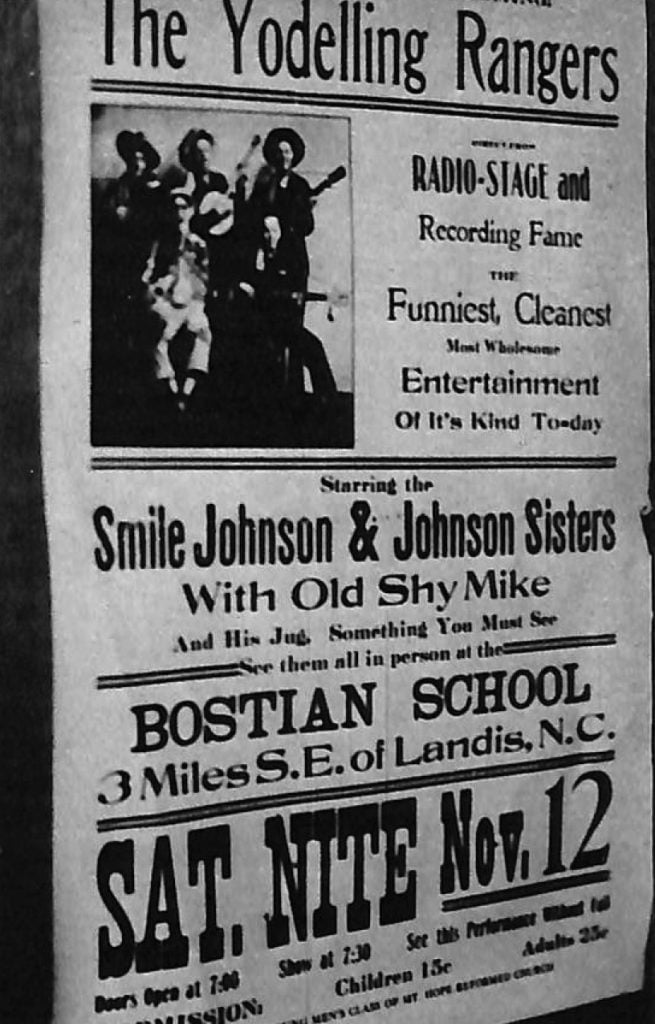

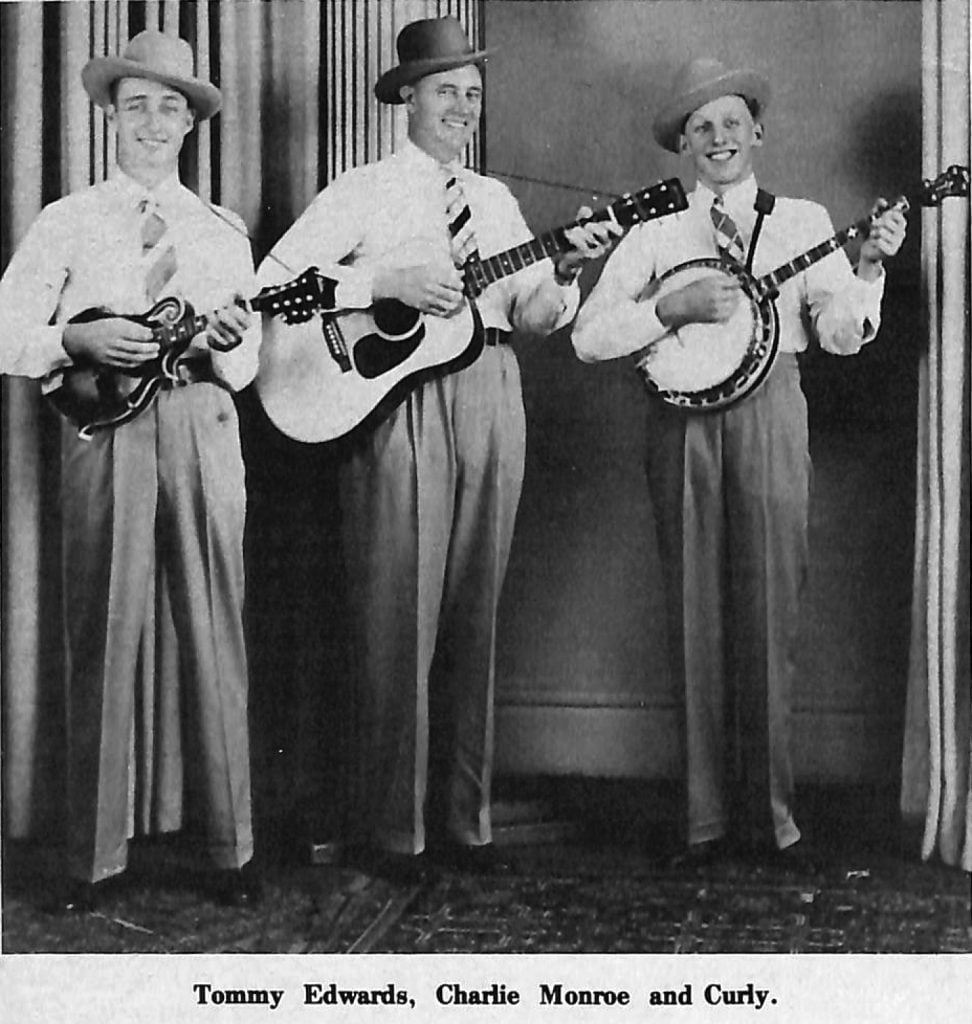

“In 1935, my brothers and I organized a group called The Yodelling Rangers. We started our first radio show back in Salisbury, North Carolina, about nine miles out of China Grove. It was three days a week, for the Russell Furniture Company there in Salisbury. Then in 1938 I drifted a little further out in show business. Bill and Charlie Monroe had split up and Charlie came in where I was doing a radio show with my brothers, wanting me to quit my brothers and go with him. That was a hard lick, because I had never been anywhere, except to Salisbury; and most of the time we went there in the two-horse wagon. Everywhere we would play a show in those days, I would look up and Charlie Monroe would be in the audience and he’d say, ‘I’ve got to have you in my group,’ and I’d say, ‘Charlie, I’m not leavin’ home.’ This went on for several months, into 1939, and during this time he offered me a salary which was pretty fair in those days, but I still wasn’t going. Later on he came up with the ante a little more and it sounded good, so we loaded up and headed for Wheeling, West Virginia, at WWVA’s Old Barn Dance, they called it the Wheeling Jamboree. We organized the Kentucky Pardners. Tommy Scott was another of the original members, and he wrote the theme song for the band.

“I carried a tenor banjo back then and that was the loudest instrument you ever heard. Hit that thing and you could hear it a country mile. Charlie said, ‘We’re going to have to calm this banjo down,’ so we took and put some rags in the back of it and he gave me a felt pick to calm the tenor banjo down.

“When Bill Monroe came in on a fifty-thousand-watt radio station—which was WSM — Charlie decided that he wasn’t going to be outdone; he was going to a fifty-thousand-watt radio station too. We went to Louisville, Kentucky, WHAS, which was fifty-thousand-watt, and that put him right up with Bill then.

“Tommy Scott and I left Charlie Monroe in Louisville in 1941 and we organized in Anderson, South Carolina. I had no money as usual, and a boy named Lonesome Luke had an F-4 mandolin. I had never played a mandolin, never had one in my hands. I borrowed the money, $42.00, from our sponsor there to buy my first mandolin.”

By the time Lester Flatt joined Charlie Monroe’s Kentucky Pardners, Curly had left. When Lester joined Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys, Curly, like many others, noticed Flatt’s impact on the sound of the younger Monroe brother’s band.

“Down home we’d listen to the Grand Ole Opry on Saturday nights. We didn’t listen to any other radio stations back then very much because there weren’t too many other radio stations. After Lester, and later Earl, joined Bill there was so much difference in that sound, anybody I talked to would say, ‘What on earth has happened to Bill Monroe? His sound is just out of this world.’ They’d tie up the Opry every time that band stepped up to the mike.”

After years in the shadow of Bill Monroe’s legend, Flatt and Scruggs, in 1948, undertook the task of building their own. According to Flatt, they “went up into Virginia and messed around a few days gettin’ organized, then came back to WCYB in Bristol and went to work.” It was immediately apparent that the public wanted what the Foggy Mountain Boys were offering. The first week of their tenure at WCYB they went into Kentucky to play a show.

Curly Seckler followed the progress of Flatt and Scruggs, and, on a night off in Virginia, he went to one of their shows. Though he was impressed with them, he found Flatt less than impressed with him. “After I left that night Lester said, after we’d talked about this and that and the other, that I was nothing but a smart-aleck.

“I had this big Packard Clipper, and I got it all stretched out and I came rolling in there like I owned the whole state. He just got the impression of me that I was just a smart-aleck and didn’t have thirty cents in my pocket. Later on, Lester called me in Augusta, Georgia, and wanted to know if I wanted to come to work with him and Earl. That was 1949, ‘long about March the seventeenth. I was working with Jim and Jesse and the Virginia Boys. I came up fast, but not in the Packard.

“The light has been green since the day Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs organized the Foggy Mountain Boys; there’s been no let-up. They were making money when I came in with them and they continued to make money. I can truthfully say that there was no struggle whatsoever. In the early fifties, we were stacking people just as deep as you could put them anywhere we went. We worked a lot of these school houses and one of our main licks back in the early fifties was drive-in theatres. We’d get up on the concession stands and we had a tent in case it rained. Of course, the neighbors who came to see us were in automobiles. They were in the dry, and we’d run our sound system through the speakers, just as if the movie was on. A lot of the people, if it wasn’t raining, would get out of their cars and come down to the concession stands. Later we got to doing these package shows with people like Cowboy Copas, Bill Monroe, Lefty Frizzell, Kitty Wells, Johnny Wright and Jack Anglin and people like that.”

It wasn’t all hard work and long hours, though, as illustrated by the following anecdote from Lester Flatt. One night, while crossing the Smoky Mountains they discussed the bears living in the area. As Lester Remembered:

“We kept seeing one just every once in a while as we were going across and I was brave, because I didn’t think we were going to stop. I was saying that I’d like for one to come out of the underbrush and I’d thrash him good. We went on and played the date, and when we came back that night, we got right on top of the mountain and our lights went out. Curly was lying on the back seat, supposedly asleep; hadn’t moved for thirty minutes that I knew of. I got out there and got to messing with the car and I don’t know how he did it, but Curly eased the door open without making a sound, got a rock and threw it up into the treetop right over where I was standing. I don’t know where that car door is today, but when I went in there I think I tore it off. We were all trying to get in that one door!”

Curly left the Foggy Mountain Boys twice, the first time shortly after joining the band. “The first time I went back to Bristol, Virginia, and went to work with Carl and J.P. Sauceman at WCYB. I stayed there quite a little while, then I went to work with the Stanley Brothers for about three months. Don Horton in Lexington, Kentucky, called me about bringing a group to Lexington and he said he’d like to have the group I was working with. At the time I was working with Ralph and Carter Stanley, so I took them to Lexington in early 1950. We worked up there a while, then Carter and I had some words. They weren’t serious words, but we just couldn’t get along. We got Jim and Jesse and the Virginia Boys and brought them in, and we worked the barn dance they had there in Lexington at the time on WVLK. I got to be on Jim and Jesse’s first recordings on Capitol Records, and one number we did was one I wrote called ‘Purple Heart,’ as well as some gospel numbers. I think I did a couple of sessions of records with Jim and Jesse back in 1952. Those have been big records for them. I know, because I still draw royalties from ‘Purple Heart,’ and some of the numbers I had that they did. But I did not play mandolin with Jesse McReynolds around. Jesse McReynolds is one of the finest mandolin pickers in the field.”

When Curly returned to Flatt and company in 1952, he was just in time to see the band enter the most prosperous and creative decade of its existence. Under the sponsorship of Martha White Mills, The Foggy Mountain Boys moved to WSM and into television, and thereby into new areas where this music had never been heard before.

“We were in Knoxville, Tennessee, and Efird Burke was the Martha White salesman back in those years and I think that at the time he lived in Lebanon, Tennessee. Anyway, he got to coming out to our shows and he liked us. Everywhere we would go, just about, he’d be there, and he would come around and start talking about Martha White and this and that and he eventually said something to Lester about how would they like to work for Martha White? Well, they weren’t interested. Then we were playing a little old theatre and here comes Mr. Burke and Cohen Williams, the president of Martha White Mills. They got to listening and Mr. Williams liked what he heard, so they set up a date at Mr. Williams’ home here in Nashville to talk this thing over. Mr. Williams said that they were the most unconcerned men he had ever talked to about business. It seemed like they had everything and that he was just another sponsor. They were out on his back porch talking and there were some rabbits running around in the back yard. Lester got to talking about hunting rabbits and that’s how they got together with Martha White. That was 1953, and we’ve been with Martha White ever since.

“We used to do our shows with one microphone, just in and out, back and forth. Alot of people sat in the audience watching us maneuver on stage and wondered how we could do it without running into each other. We knew what we were going to do if you were playing a break, what time you were scheduled to come in. Later on we brought in a number two mike. Lester would say that the reason we didn’t use more mikes was that we couldn’t afford them. We brought in a bass mike later on, but we used to never use a bass mike. I can remember back when a lot of the schools we played didn’t even have electricity and we used old gas lanterns. They’d pump up to make the light—and they didn’t have any sound system.

“We would take one day a week to tape the radio shows. I believe that would come off about Tuesday. Back when we started they were live and we did them live year in and year out. Then they got to taping and that gave us a break to do long-distance touring, but we used to go in and out and did them live. We’d tour just a short way, a hundred or two hundred miles and back in. Then we’d do the early morning show live the next morning.

“Lester always put on a clean show and it was down-to-earth and a family-type show, and I’ve seen the day that you couldn’t get enough of a field to put the people in that the group would draw back in the earlier years. And too, his songwriting; you can’t beat it. When you can beat Lester Flatt writing songs, bring them to me; I want to hear them. And the number of songs he wrote. Back in the fifties, he was writing four or five a week. Lester writes songs that really get to the nitty-gritty base of a song. It’s not just a thing that springs up overnight, writing a song. Lester gave them some thought and you can tell that by listening to them.” When Curly left the Foggy Mountain Boys in 1962, it was his intention to retire from the music business.

“I got into a business practically of my own in the trucking field, stayed in it twelve years and I did all right. Then these bluegrass festivals got to starting across the country, and there’d be people calling here, promoters asking if they could get me to do a bluegrass festival. For the first couple of years I didn’t want to mess with it, but later on I did get to play at a few of them. Lester and I would be at many of the same festivals and we would do a number or two together and get to talking and he wanted to know if I wanted to come back as one of the Nashville Grass. I was not much interested in it at the time. We discussed it for some length of time, probably a year or so before we could get an agreement together on terms. I didn’t know if I could stay on the road like we used to, so we made it a temporary arrangement. The temporary arrangement lasted for over six years.

“When I went back with Lester this last time I went in with my guitar and I told Lester that I’d carried the mandolin for twenty years and if a man’s not learned to pick it in twenty years he’d better lay it down. I wasn’t tops on the mandolin. I wasn’t a Bill Monroe or a Marty Stuart. What I did was just something I did on my own and there were very few numbers I did any lead on at all on the mandolin. I’m a rhythm man and I think I do a fair job at that. Aside from the fiddle, the mandolin is the hardest instrument you’ll ever pick up and try to play. If it hadn’t been for my singing, I would never have gotten to first base in the music field.

Curly considers Lester Flatt “The King Of Bluegrass Music,” due to the powerful influence Flatt has had on the development and popularization of the music. Curly often mentioned his belief that the Country Music Association should finally recognize Flatt’s contributions to country and bluegrass music and induct Lester Flatt into the Country Music Hall Of Fame.

“I’m not knocking anybody on this. Bill Monroe is the Father Of Bluegrass Music, and he deserves credit for that. Other folks deserve credit too; but I think there’s a place in the Country Music Hall Of Fame for the King Of Bluegrass Music, Lester Flatt.”

Curly’s first solo album was released a few years ago, and since then he’s done a considerable amount of guest artist work in studios with John Hartford and Marty Stuart, among others. He is currently preparing a second solo album. “Dave Freeman wanted me to do an album for the County label—and I did— but when he first started I didn’t want any part of an album. I’d gotten into another field, did pretty well and I just didn’t want to get back into music. Well, Dave kept on and eventually I got with the Shenandoah Cutups and we did an album several years ago, before I came back with Lester. The album has done really well, and Dave did exactly what he said he would do in doing the album, and I appreciate that.

“John Hartford is a good friend of mine, and, of course, of Lester’s too. I enjoyed doing ‘All In The Name Of Love’ with John as much as I’ve enjoyed any album I’d done in a long, long time. We did several different numbers and I was just tickled to help him out on it. We thought we’d do that one together and see how the public liked it, and we’re planning to do some more recording together. It was an honor to get to work with John Hartford, and I appreciate what he wrote on the back: ‘The Old Trapper himself, singing the harmony parts.’

“Lester nailed me down with that ‘Old Trapper’ years ago. He’d introduce me on stage as ‘The Old Trapper from China Grove, North Carolina.’ Down through the years we’d play at places and a lot of the old-timers would come up askin’ me what kind of traps I sell. I wouldn’t know a trap from a pea-hauler! Lester got a big kick out of it because people thought I really did a lot of trappin’, that I had all kinds of traps and I’d caught all kinds of game; but I never trapped anything in my life but my wife!”

Next to Lester Flatt, Curly’s closest friend in the Foggy Mountain Boys was fiddler Paul Warren. “Paul came into the band in ‘54 and stayed right at twenty-three years, until about a year or so before he passed away. Paul Warren was one of the finer bluegrass fiddlers and he never got the credit I think he deserves. Paul was a down-to-earth good fiddler and a hard worker.

“One thing I was glad to see Paul Warren do before he left the Nashville Grass was to record a number called ‘Black-Eyed Susie.’ We turned him loose at the Grand Ole Opry just a short time before he retired and he tied the Opry in a knot with it.

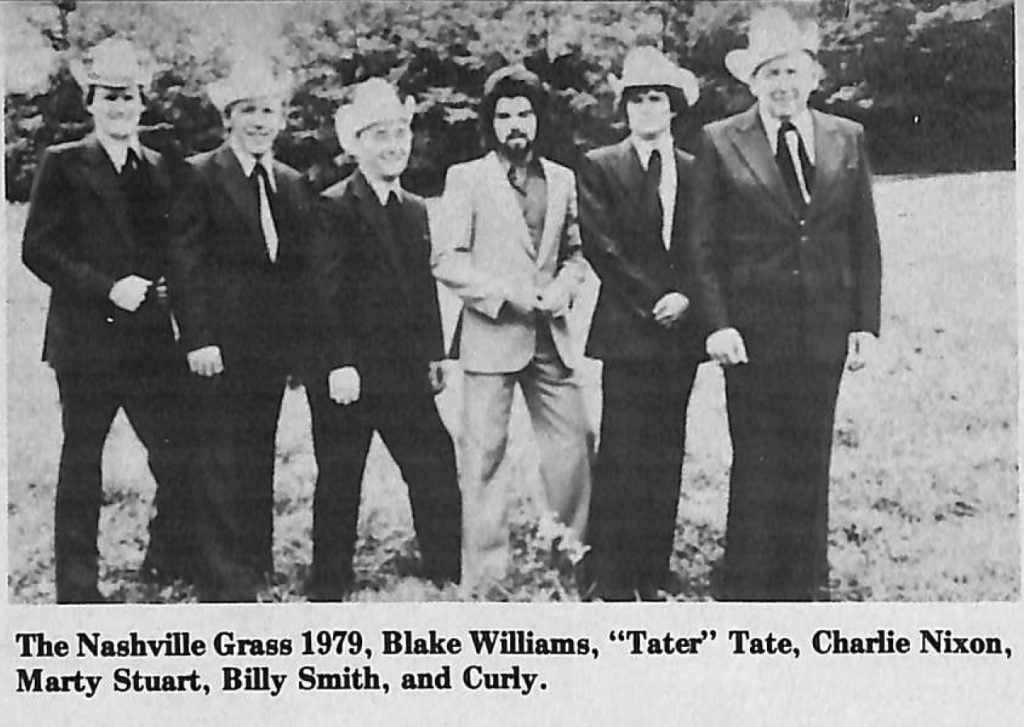

“We went for about three or four months and used Marty Stuart on the fiddle. Marty did a great job. In fact, we used Marty and Paul on some of our albums and they did some twin fiddling. Finally we saw that Paul wasn’t going to make it to where he could come back, so we got in touch with Tater Tate.

“I knew Tater before I knew Paul Warren. In fact, we worked together before I ever met Paul. What we needed was a gentleman, a man and a fiddler. It’s hard to find all three, but Tater Tate is that order. Today he’s one of the finest fiddlers you could find to fit our group.” After twenty-five years at the Grand Ole Opry, Curly has seen many changes there. “The Grand Ole Opry, when it was at the Ryman Auditorium, was great, and it’s still great where it is now. If it hadn’t been for the music there would be no Grand Ole Opry. It was built on down-to-earth music. Now they’ve got a little of everything on there and I think the time will come—and I don’t think I’ll live to see it—after some of these older people get out of it, that the Grand Ole Opry will get like that song Lester wrote one time, ‘Don’t Get Above Your Raisin’, but they’re going to get above their raisin’ there. I think it’ll be the Opry, instead of the Grand Ole Opry. You let people like Ernest Tubb, Bill Monroe, Roy Acuff, Lester Flatt, and Hank Snow get out of it, what’re we going to have left? The Opry’s going to change, and it’s already on its way. That’s an awful thing to say about something going as long as the Grand Ole Opry, but I believe it’s going to switch.”

Not only has the Opry changed but so, according to Curly, has the way the Nashville Grass introduces new material on records. “A lot of times we would do a number quite often before we’d record it, but you can’t do that today. You get out and get to singing a number over here and first thing you know another group has picked it up and released it before you can record it. There are so many in the field nowadays you can’t do that.

“Lester used to toss up the old number I wrote, ‘That Old Book Of Mine.’ Lester and I hadn’t sung that but once or twice in our lives when we recorded it. Lester turned to me in the studio and said, ‘Seck, have you got a number you’d like to record?’ I said I had one but we’d not done it much. He said, ‘Throw it on the rack and let’s run over it.’ Back then I could tell you whether he was going to take a long breath or a short breath. You can hear it on that record and it sounds like we’d been singing it for ten years.

“We’d walk into a studio at Columbia and we’d have three or four hours at a session, but we’d go through the numbers and there were no let-ups whatsoever, no mistakes. We’d have a session through before you could snap your fingers.”

When on the road, Curly takes a keen interest in the new, younger bands playing festivals with the Nashville Grass. “The kids growing up today have all the opportunity in the world to sit down and get lick-for-lick what we did in the past. Marty Stuart will tell you that he sat up night after night under the covers to keep the sound down and to get the licks down on the mandolin that so-and-so got down through the years. Most of what I learned my mother taught me, or I heard it on the Grand Ole Opry. There was an old record player that we’d crank up, but nobody was puttin’ out much music in those years.

“I think any kid today needs to come up just a little like I did. Kids coming up today won’t keep it down to earth. They want to get into more modern picking; they don’t want to hold it down to the original stuff that we did down through the years. Stick to the script; that’s how I feel about the music.”

On October 16,1976, China Grove, North Carolina recognized its famous native son by celebrating “Curly Seckler Day,” paying tribute to his “valuable contributions made to the development of country music from 1935 to the present time.” With his past and present successes considered, his future looks bright.

“I don’t know what I’d do if Lester retired. I hope it never happens in my lifetime, because I came back into the music field to stay. We did a few months on the road without him this past year, and it seemed like every time we’d leave, the bus would want to turn around and go back. It seemed like the the bus wasn’t running true, that it was runnin’ a little sideways without him in that big chair. Everywhere we went the people accepted us, but I think it was more that the people felt for us because Lester wasn’t out there with us. When we’d go out and try to do a show without Lester Flatt, it was just like trying to eat ice cream without a spoon; it’s hard to do.

“My mother lived to be eighty-three years old and I remember her saying the last year or so that she lived that it seemed that one year was just like snapping her fingers, and time is getting to be that way with me now.”