Home > Articles > The Archives > Mac Martin and The Dixie Travelers: A Bluegrass Institution in the Steel City

Mac Martin and The Dixie Travelers: A Bluegrass Institution in the Steel City

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

October 1989, Volume 24, Number4

Whereas bluegrass band leaders and some musicians have long had an enduring quality about them—Bill Monroe being only the most obvious— continuity of personnel in bands is much less common. One quite atypical group in bluegrass music that has long endured with a consistent quality product may be only a part-time band, but they have gained respect among fans around the world. This band, Mac Martin and the Dixie Travelers, has become a virtual institution in the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, area. The key members of the band on guitar, banjo and fiddle have been together for more than thirty years. Other members have been part of the current group for over ten years. Through more than a quarter century of recording, the Dixie Travelers have also released nine albums of quality music and are continuing to turn out more.

Although Pittsburgh maintains a well-deserved reputation for ethnic diversity, particularly East European, the Steel City can also boast its share of Appalachian migrants to provide an audience for the music of the Dixie Travelers. Mac Martin comes from Irish stock (Galway). His real name is William Colleran and his forebears made up a part of the great Celtic exodus that emigrated from the Emerald Isle for several decades beginning in the 1840s. Born in Pittsburgh on April 26, 1925, Mac reports that some of his first cousins who reside in Ireland also play music, so his musical talents are “in the blood.”

As a youngster in Pittsburgh, Mac listened to a lot of country music on the radio. Favorite programs included the Grand Ole Opry and Wheeling Jamboree. He also gained a great appreciation for the recordings of folks like the Carter Family and the Monroe Brothers as well as being attracted to the songs of lesser yet still significant duets like the Dixon Brothers and the West Virginia team of Bill Cox and Cliff Hobbs. By the early 40s, Mac had taken up the guitar and began to try recreating the music of his favorites. At the time, he pursued this interest pretty much as a hobby or for pasttime with little thought of a professional or semi-professional career. However, in this process Mac picked up a tremendous song repertoire. Bill Vernon quotes an unidentified Dixie Traveler fan noting that Martin “knows ‘at least a verse and a chorus’ of every song he has ever heard.” Even if this claim constitutes a slight exaggeration, it still comprises an esteemed compliment to his mental storehouse of song lyrics.

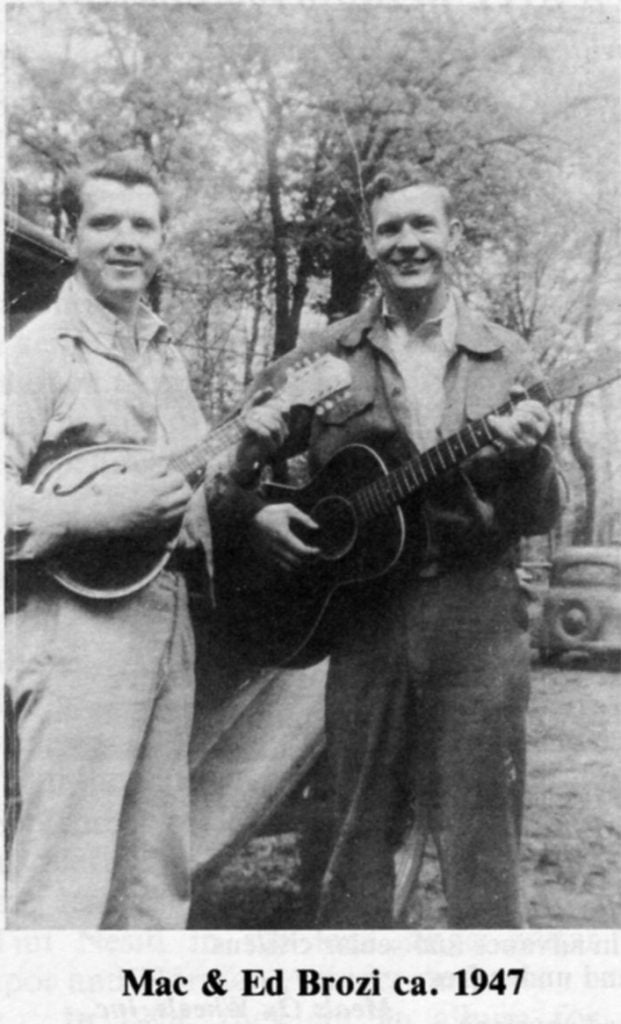

Along about this same time, Mac met a fellow named Ed Brozi. The two spent a lot of time picking and singing together. They also looked around in the used record departments of stores and Martin developed fondness for harmony duets. Brozi had some experience as a medicine show entertainer and helped the young Irish-American further develop his still increasing repertoire.

After finishing school Martin entered the U. S. Navy. His experience as a Seabee eventually took him across the Pacific to the Isle of Okinawa. His guitar reached the occupied island, too, and Mac continued to add new lyrics and tunes to his repertoire.

Not long after the war when Mac returned to civilian life, he put his first country band together and in 1948, bought a new Martin D-28. In the previous couple of years Bill Monroe’s classic band of Lester Flatt, Earl Scruggs, Chubby Wise and Cedric Rainwater had performed at the Grand Ole Opry and immediately after Lester and Earl formed their own group. The Stanley Brothers were also getting started although it took a little longer for their sounds to reach Pittsburgh. The revitalized form of traditional country sounds that these bands played came to be the musical style that Mac and his band would favor for the next forty years. He described his first band as playing bluegrass music “without the banjo.”

This group went by the name Pike County Boys. In 1949, they began playing regularly over WHJB radio in Greensburg, Pennsylvania. This station had a sizable audience in southwestern Pennsylvania and like WMMN in Fairmont, West Virginia, it might be described as a miniature WWVA. Band members also included Bill Higgins on fiddle and Bill Wagner on bass. Three “Bills” were too many for one band, so Bill Colleran took the name Mac Martin and has since used it as a stage and musical name. In 1950, a mandolin player from Kingsport, Tennessee, named Earl Banner rounded out the band. He and Mac often did Monroe Brothers duets or as Mac considered them at the time to be Lilly Brothers duets. The Lilly Brothers played at WWVA in that period and Mac considered them really to be in their prime in those days with a very broad repertoire, hardly ever singing the same song twice (at least on radio). Mac came to know the Lillys pretty well, but only later did he realize that many of “their” songs had been recorded earlier by the Monroe Brothers, Callahan Brothers, or Blue Sky Boys. Mac’s band played on the station gratis and advertised their few showdates—dances and occasional parks—and finely honed their feel for the music. Mac always worked a day job, being an accountant for A&P Food Stores from 1948 until 1969 and afterward for Volkwein Brothers music store.

After two or three years of weekly radio work, the Pike County Boys stopped going to Greensburg. For a brief time Mac, Earl and Bill Higgins played on station WHOD in Homestead, Pennsylvania. Then for a time Mac also began to play some banjo although he never considered himself very good. Following the short stint on the Homestead radio outlet, Mac and Earl Banner worked for several months just as a mandolin-guitar duet, mostly in clubs on the north side of Pittsburgh.

Mac had married in 1952 and the first of his five children was born in 1954. About this time a young fiddler named Mike Carson, originally from McKeesport where he had been born on June 27, 1937, heard Mac and joined forces. A little bit later, a banjo player named Billy Bryant also became part of their aggregation. Born on May 4, 1938, young Bryant had some prior radio experience at WEIR radio in Weirton, West Virginia. Carson had played country fiddle from childhood, but became a convert to bluegrass about 1952, developing in the words of Bill Vernon a knack for being “particularly adept at writing original fiddle tunes with unusual and intriguing chord changes.” Bryant had played guitar before learning banjo and could do fine lead guitar work when an arrangement called for it, in addition to what Vernon terms “His crisp, lean, bright ‘attack’ on the banjo.” The addition of a local Pittsburgh bass player named Slim Jones brought the full Dixie Travelers bluegrass band to maturity.

Irregular club and radio work in the greater Pittsburgh area characterized the first two or three years of the Dixie Travelers operation as a semi-professional band. Beginning in 1957, they began playing on Saturday nights at Walsh’s Lounge, 6018 Broad Street. This club became their principal base for the next nineteen years. Sometimes they also played on Fridays as well and in later years the management took a congenial attitude toward the band whenever they received an opportunity to make a festival or concert appearance elsewhere. In the process, a traditional band made up of part-time musicians perfected their talents and techniques making themselves a bluegrass institution and Walsh’s the bluegrass locale in the Steel City.

The Dixie Travelers had been together as a group for nine years and at Walsh’s for six when they made their first records. The National Record Mart in Pittsburgh’s parent company had a label called Gateway. (Not the same as the Carl Burkhardt firm in Cincinnati of similar name that released early efforts of the Osbornes, Red Allen, etc.). The Dixie Travelers recorded sufficient material for two albums; one album plus an additional single was released.

Much of the material on the Gateway recordings consisted of standard fare that the folks running the company wanted such as “Roll On Buddy,” “Salty Dog Blues,” “Orange Blossom Special,” “Banks Of The Ohio” and “Bluegrass Breakdown.” Still, Mac managed to sneak in a pair of rare gems from the early years of recorded bluegrass, the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers’ “Nobody Cares” and the Speedy Krise song by way of Mac Wiseman, “You’re Sweeter Than Honey,” as well as the classic Stanley song, “The Angels Are Singing In Heaven Tonight.” The single included an original instrumental, “Mustang,” backed with the common favorite, “Sittin’ On Top Of The World.”

Continuing their regular appearances at Walsh’s, the Dixie Travelers experienced their first personnel change in 1965 when Slim Jones left the group. His replacement, Frank Basista, had known Mac since his radio days at Greensburg. Only a few months younger than Mac, Frank played mostly bass with the band, but also had a flair for comedy. He could also play mandolin, guitar and fiddle and sometimes got in a few licks on the latter during the seven years he spent with the band. Banner left the group about 1967, leaving the band without a regular mandolin player for several months.

In 1968, the Dixie Travelers began a four-year association on record with the Rural Rhythm label, owned by the late Uncle Jim O’Neal of Arcadia, California. O’Neal had some fine bluegrass talent on his label at the time including Red Smiley’s Bluegrass Cutups, Don Reno and Bill Harrell and Mac Wiseman as well as that durable old-timer J.E. Mainer along with some lesser-known bands. O’Neal liked twenty-song albums and Mac generally liked the format of two-thirds of his repertoire consisting of vocal numbers and one-third instrumental. While some of the instrumentals tended to be a bit brief, Mac believes that the Dixie Travelers gave record purchasers a good deal musically for their money. Tom Knight, a fan and long-time friend in Pittsburgh, engineered and produced the albums for them, all of which were recorded locally. The initial offering, “Travelin’ Blues” (RR 201), consisted of instrumentals featuring the talents of Carson and Bryant. Although Earl Banner’s picture appeared on the album cover, he had actually left the band by the time of the sessions which contained only the foursome of Billy, Frank, Mac and Mike.

By the time Mac Martin and the Dixie Travelers did their second Rural Rhythm album in 1969, they had returned to full strength. Shortly after the recording of “Travelin’ Blues,” a twenty-two-year-old native of Santa Monica, California, began sitting in with the group and within a few weeks became a regular member. Bob Artis brought an intellectual interest to the band that rivaled Mac’s as well as a strong tenor voice and an excellent mandolin style. Bob became interested in bluegrass at fifteen and within three years had taught himself to play several instruments and organized a band. Bob would spend several years with the band and become leader after Mac took a leave of absence in the summer of 1972. Artis also possessed a fine talent as a writer and penned the first respectable book on the music, Bluegrass (New York: Hawthorn Books, Inc., 1975).

In the meantime, they continued playing at Walsh’s and occasional appearances elsewhere. Their second Rural Rhythm album, “Goin’ Down The Country” (RR 214), featured bluegrass arrangements of such tasteful old-time numbers as Bill Cox and Cliff Hobbs’ ‘‘Drift Along Pretty Moon” (as “Southern Moon”), the Delmores’ “Blue Railroad Train” and George Morris and Leonard Stokes’, “We Can’t Be Darlings Anymore,” among its twenty cuts. Their third album from 1970, “Just Like Old Times” (RR 232), contained such rare classics as Jake Landers’ “The Last Request,” Connie Gateley’s “How Will The Flowers Bloom” and Charlie Monroe’s “Is She Praying There.” The last effort for Uncle Jim entitled “Backtrackin’” (RR 237) in 1971 included such forgotten classics as Molly O’Day’s “If You See My Savior,” the Carlisle Brothers’ “She Waits For Me There” (as “A Silent Place”), and Melissa Monroe’s “Guilty Tears.” The last two Rural Rhythm albums can be counted among the few which contained liner notes, both uncredited, but from the expert pen of Bob Artis.

In 1972, the Dixie Travelers switched to David Freeman’s County Records. Freeman and Bill Vernon came to Pittsburgh to see them a couple of times and the band went to New York City twice. Mac’s skills at song selection perhaps peaked on the well recorded album waxed for this label. Highlights included a fine rendition of Roy Acuff’s “Just To Ease My Worried Mind,” Buddy Starcher’s “A Faded Rose, A Broken Heart,” Walter Bailes; “Pretty Flowers,” and Charlie Bailey’s “Have You Forgotten.” Mike Carson contributed a fine new rendition of his original fiddle tune “Natchez” and Billy Bryant’s “Dixie Bound” ranked among the instrumental showcases. Bill Vernon contributed a sensitive set of liner notes which explained the true essence of what makes the music of the Dixie Travelers so compelling to lovers of traditional bluegrass.

By the time “Dixie Bound” (County 745) rolled off the presses in 1974, Mac Martin had taken a leave of absence from the Dixie Travelers. Twenty years of weekend playing convinced Martin that he needed a rest from the musical grind. He departed in September of 1972, and Frank Basista also left. The band continued on under the leadership of Bob Artis, adding Tim Nesiti in the lead singer-guitar spot and Norman Azinger on bass.

In 1974, they cut an album for Paul Gerry’s New York state-based Revonah records “Free Wheeling” (Revonah 914). Band members continued to display excellent expertise in song selection. Billy Bryant contributed the title tune, an original banjo number while Mike Carson played a fine rendition of a forgotten Tommy Jackson classic, “Run Johnny Run.” Vocal showcases included the Church Brothers “Way Down In Old Caroline,” the Kentucky Travelers “Dreaming” and a popular number done by many country artists in the ’30s “Rattle Snake Daddy.”

Bob Artis left the group in October, 1975, to play with the Dog Run Boys, a more progressive styled band. Edgar “Bud” Smith, a mandolin picker and tenor singer from Wellsburg, West Virginia, who had previously worked with some bands in the Wheeling area, became a regular Dixie Traveler in October, 1975. For a few months in the summer and fall of 1975, the band restyled themselves the Steel City Grass, a name that never quite caught the public fancy and led them to soon revert to their original sobriquet. Billy Bryant also branched out somewhat in the mid-seventies, starting a separate band called the Bluefield Boys while retaining his older affiliation as well.

By 1977, Mac began getting back into the swing of things, appearing at Walsh’s on Friday nights while the Dixie Travelers worked there on Saturdays. By the end of the year, the entire ensemble switched their principal base of operations to Gustine’s, a club run by former Pittsburgh Pirate third baseman (1939-1948) Frank Gustine, located at 3911 Forbes Avenue. The band worked at this locale for about six years.

Although the group never toured extensively on the festival circuit, they did play at a few of these events each year, chiefly in Pennsylvania and adjacent states. They also did concerts at several colleges and universities over the years.

In October, 1977, the Dixie Travelers returned to recording, waxing their “Travelin’ On” album for Revonah (RS 928). Outstanding cuts included a bluegrass arrangement of the early Marty Robbins song, “At The End Of A Long Lonely Day,” the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers’ “That’s Why You Left Me So Blue,” and a lesser known Bill Monroe number from 1964, “Mary At The Home Place.” “Gethsemane” constituted a fine gospel cut that Byron Parker’s group waxed in the forties, but the Dixie Travelers learned it from the Columbia recording of 1957 by the Carl Smith Trio.

Moving into the decade of the ’80s, the Dixie Travelers continued playing the brand of bluegrass that has caused them to achieve regional acclaim and wide acceptance if not widespread fame. By this time, younger musicians like the Johnson Mountain Boys (albeit with youthful appeal) had appeared on the scene and won broad audiences for the kind of sound and style that Mac and his boys had always favored. Mac became a strong booster of the Johnson Mountain Boys, Larry Sparks and other younger musicians of that generation who showed so much respect for the traditional brand of bluegrass.

Following the long stint at Gustine’s they spent a year or so as an itinerant band with no permanent place to play. This ended in 1984, when the Travelers settled in at the Elizabeth Moose Lodge where they have appeared at least monthly and often every other week for about five years. Name bluegrass bands from outside the Pittsburgh area appear there with some regularity, too (see story by Cathy Moffat in the January, 1989 BU) including the Country Gentlemen, Bluegrass Cardinals and Larry Sparks’ Lonesome Ramblers. Mac reflects with some pride that the Johnson Mountain Boys played one of their last concerts there. He also thinks that such quality “competition helps keep the Dixie Travelers on their toes.”

In 1987, after a near decade of absence from the recording studios, the same five musicians as had cut the “Travelin’ On” disc did a new album. For the first time, they utilized the services of some additional guest musicians: namely Ron Mesing, Dobro; Bob Martin, lead guitar and Larry Zierath, rhythm mandolin. The result constituted another excellent album. Released as “Basic Blue Grass” (Old Homestead OHS 90178), the record has been reviewed quite favorably. Somewhat surprisingly, a trio of songs—“Big City,” “Roustabout” and “Simon Crutchfield”—are relatively new (meaning written after 1960). Still, the presence of a pair of lesser known Monroe Brothers songs—“Some Glad Day” and “The Old Man’s Story”—remind us that Mac retains his skill to choose “new” old material. His rescue of an obscure Lilly Brothers tune from their WWVA days, “I’ll Forgive You” and Mike Carson’s rendition of an infrequently heard Chubby Collier or Benny Martin tune “Two O’clock” demonstrate their capacity to draw from memories of old radio broadcasts. As of this writing, the Dixie Travelers have partly finished another album designed to commemorate their thirty-fifth anniversary as a band.

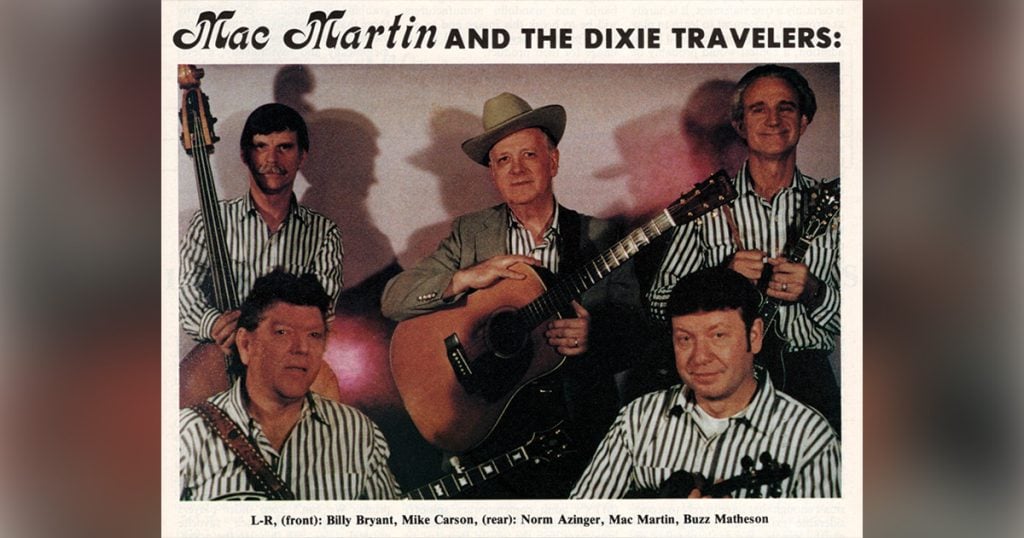

None of the Dixie Travelers has ever been a full-time musician. In one sense, Mac believes that the semi-professional character of the band have enabled them to develop themselves. Their leader points out that they exemplify the advice offered in the 1973 Country Gazette album, “Don’t Give Up Your Day Job.” In addition to Mac’s work as an accountant, Mike Carson serves as assistant manager of a supermarket while Billy Bryant works in construction for Mac’s brother-in- law. Norm Azinger is a telephone company employee and Bud Smith works for the employee-owned Weirton Steel Corporation. In the winter of 1988-89, shift work has become something of a problem and Buzz Matheson, a veteran bluegrass musician from Warren, Ohio, has filled in for him. Besides their work in the clubs and festival appearances, they have worked several times at the annual bluegrass night held on station WWVA’s Jamboree U.S.A.

In conclusion, one can reflect on the thirty-five years of Mac Martin and the Dixie Travelers with considerable positiveness. It has not been their fate to achieve the fame of a Bill Monroe, a Lester Flatt, an Earl Scruggs, or a Ralph Stanley. However, there can be no doubt that they have carried on the tradition in a most high manner. They also exemplify a capacity for creativity and innovation while remaining true to the spirit of the “founding fathers” of bluegrass. In the aesthetic sense, we as adherents of the “bluegrass sound” can expect no more from its best practitioners.

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

I lived in Pittsburgh in the 1970’s and had the pleasure of catching the Dixie Travelers at Walsh’s. Pittsburgh, at that time had a thriving OT and BG scene a lot of it centered around Stu Cohen’s Music Emporium in Shady Side. Stu had a big old mansion and had memorable parties there, including the annual Scrimshaw Mtn. Festival. I was a sometimes student at Pitt, but was constantly distracted by all the good, live music in town. I did manage to eventually graduate, though. -Jim