Home > Articles > The Archives > Fiddler Turned Scholar — Blaine Sprouse

Fiddler Turned Scholar — Blaine Sprouse

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

November, 1988 Volume 23, Number 5

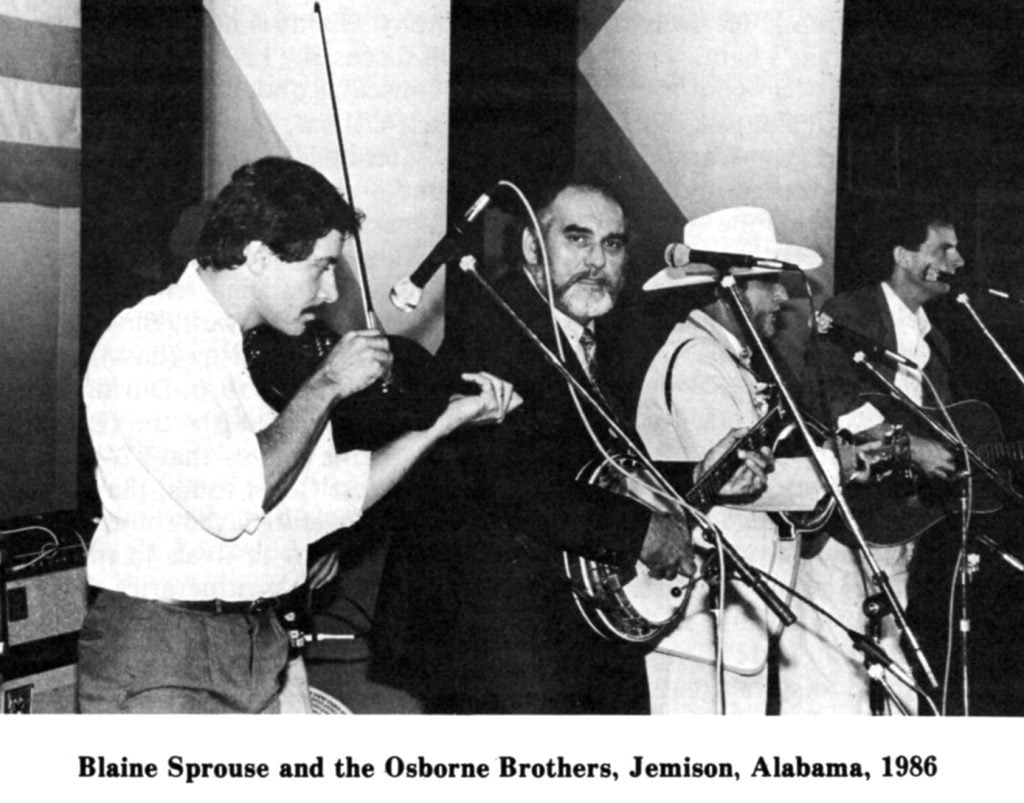

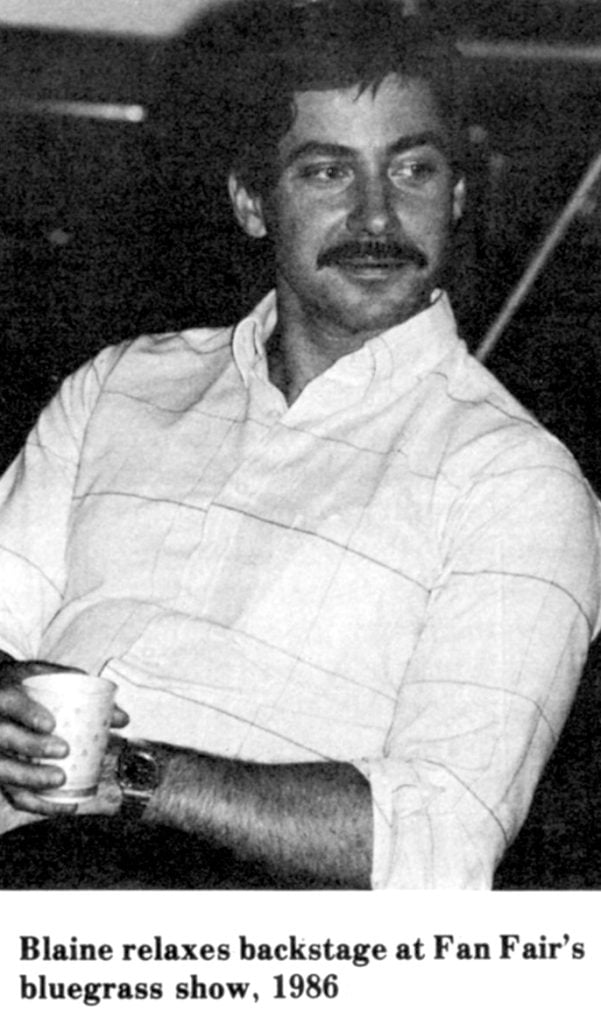

On February 15, 1987, Blaine Sprouse, who has been hailed as one of bluegrass music’s finest fiddlers, made his last stage appearance as a member of the Osborne Brothers band, an event that brought to a close one of the many phases of a varied career. With plans to pursue, on a fulltime basis, his college education that began in 1986 when he enrolled in night classes at Nashville’s Aquinas Junior College, Blaine ceased to be the familiar figure that he once was at bluegrass festivals across the country.

When he finishes his studies at Aquinas, Blaine plans to enter a four-year college—probably Vanderbilt University or Belmont College, both located in Nashville—to study for a degree in business administration. After graduating from college he has his sights set on a career in the world of business. For the many bluegrass fans who may fear the loss of one of their favorite fiddlers, Blaine has some words of reassurance. “I’m not completely removing myself from the music scene,” he vows. “Even though I’ll be a full-time student for the next few years, I plan to participate in recording sessions, do some short tours, and perhaps make some solo appearances.”

Blaine has already been as good as his word. Shortly after his farewell performance with the Osborne Brothers, he spent 28 days in Africa on a bluegrass music-making tour sponsored by the United States Information Agency. Accompanying Blaine on the tour were mandolinist Roland White, guitarist Billy Smith, and bassist Terry Smith. Performing under the name Blue Ridge Connection, Blaine and his fellow musicians entertained foreign diplomats and local residents at embassies and cultural centers in six African countries.

In addition to providing backup work on other artists’ recordings, Blaine is collaborating with fellow fiddler Kenny Baker on an album of fiddle tunes to be released on the Rounder label.

Thus, although, in the future, Blaine’s visibility as a bluegrass performer may not be as prominent as it once was, his musical light will not be totally extinguished.

Blaine Sprouse was born on October 11, 1956, in Martinsburg, West Virginia, and grew up in Hedgesville, a suburb of that city. His father, now deceased, was the only musician in Blaine’s immediate family. “He played a clawhammer banjo and guitar,” Blaine explains. “He even had a little radio show in Winchester, Virginia, back years ago. He sang and played banjo.”

Blaine himself lost little time in developing an intertest in music. “I was about eight or nine years old,” he reminisces. “I remember we had been to see a movie about Hank Williams, Sr., and I really got caught up in his songwriting. He was my hero, and I wanted a guitar right away. I finally conned my mother into buying me a very cheap guitar, and [I] learned a few chords from my father.” When his father realized that Blaine was serious about music, he bought his young son a more expensive instrument—a Gibson. Within a short time Blaine was playing his guitar at dances and other entertainments with his father serving as chauffeur and chaperone. He recalls that his father spent a lot of time helping him with his music in other ways. “We used to sit at the house, and he’d play banjo and I’d play guitar,” Blaine elaborates, “and he’d always try to take me to every bluegrass festival that was nearby. He was really a great help. I probably would not have made [music] a career had it not been for him.”

Then Blaine decided to learn to play the fiddle. “I really don’t know what got me interested in it,” he confesses, “[but] when I was about eleven I decided that it would be neat to learn to play the fiddle.” His first instrument, which someone gave him, he describes as one “that had been busted up and glued back together.” As the gift did not include a bow, Blaine played his first tunes by picking them out with his right hand. His ambitions with respect to the fiddle, however, were not to be denied. “I saved up some money from the dances I was playing,” he notes, “and bought a three-quarter size fiddle,” complete with bow. Since he already knew his left-hand fingering, he now only had to concentrate on how to wield the bow. In a short while, he relates, he replaced the guitar with the fiddle when he played at dances.

One day, when he was about thirteen years old, Blaine heard Kenny Baker playing the fiddle with Bill Monroe at a bluegrass festival. “I was really touched by his tone,” says Blaine. “It was so rich and warm and smooth. That’s what I wanted to sound like if I could, so that’s what I shot for in my playing after that.” Thus, Blaine concedes, Baker became the major influence on his fiddle playing style.

The first bluegrass band in which Blaine played was one that included two of his cousins, Douglas and Rodney Sprouse who played bass and mandolin, respectively. “They were a local band and they called themselves the Sprouse Brothers,” Blaine observes. “They performed around Waynesboro, Virginia. During the summertime, when I was not in school, I’d go down and play festivals with them.”

The first major bluegrass act of which Blaine was a member was the Sunny Mountain Boys under the leadership of Jimmy Martin (BU, July, 1986). According to Blaine it was in 1974 that Martin heard his fiddle playing at a festival in Waynesboro, Virginia, and asked him to join his band. Blaine was with Martin for about a year during which the group made a tour of Japan.

Following his stint with Martin, Blaine dropped out of the entertainment business for a year to try his hand at cattle farming in Illinois. As a child, Blaine, like many boys, had dreamed of becoming a cowboy. “I finally got to be a cowboy,” Blaine smiles, while confessing that the fantasy was much more enjoyable than the reality. However, he adds, “It gave me a fresh perspective to know what I wanted to do. I missed playing, and I missed being on the road. So, somehow or other, I got in touch with James Monroe,” who hired him to play fiddle with the Midnight Ramblers. Blaine was with Monroe for about eighteen months. “I really had a good time with that band, because there were several people in the band that I became very close friends with.” Friendships and congeniality assume more importance when a person is spending a lot of time on the road and away from the typical avenues of human interactions. As Blaine puts it, “In this business you meet a lot of people, and you have a lot of acquaintances. That’s the nature of this business, I guess.” Unfortunately, he says, you don’t always become close friends with these acquaintances, but happily, “every once in a while you do.”

After his tour with James Monroe’s band, Blaine’s musical career took a somewhat different turn. He took a job as fiddler in a country music band—Charlie Louvin’s (BU, March, 1983). Blaine found that what is expected of a backup musician in a country band—even one as acceptable to bluegrass fans as Louvin’s—differs from the way a backup musician performs in a bluegrass band. “You’re not out front as much as you are in a bluegrass band,” he discovered. “In a bluegrass band you’re such an integral part of everything that’s happening.” But “in a country band, unless you’re playing with a band where the fiddle is a featured part of the music, you’re just there to play a little riff here, a little thing there, maybe backup one verse in the song.”

Although bluegrass music is Blaine’s “first love” and it holds an edge over country music in his stylistic preferences, he admits that to him as a performer “they both have their rewarding little things. It’s nice to be able to do both.” He feels that his tenure with Louvin’s band was a learning experience. ‘‘I couldn’t say I learned this particular lick or this particular thing. But you learn. If you’re lucky, you take something with you” as you move from one genre to the other. And he feels that while playing country music he picked up and developed “certain little progressions” that he has been able to incorporate into his bluegrass playing.

After two years with Charlie Louvin’s country band, Blaine returned to the bluegrass fold by signing on with Jim and Jesse McReynolds (BU, August, 1986) with whom he performed for two years. He describes his work with Jim and Jesse as “a lot of fun. I’ve always loved their music,” he declares, “and they’re great people.” One of the highlights of his job with Jim and Jesse was a European tour that included performances in Paris, Stockholm, Frankfurt, and London. It was also while he was with Jim and Jesse that bluegrass fans were afforded the rare opportunity of hearing Blaine sing. He, Keith McReynolds, and Tim Ellis frequently teamed up to “have a good time,” as Blaine puts it, and add some variety to the set with their triple harmony. Blaine is not too enthusiastic about discussing his singing. “I’m very self-conscious about trying to sing. I’m too self-critical, I guess.”

After he left Jim and Jesse, Blaine became a charter member of a group that called themselves the Bluegrass Band. The other founding members of this once promising ensemble were guitarist Alan O’Bryant, Butch Robins (banjo), David Sebring (bass), and Ed Dye who played Dobro. During the ten months he was with the Bluegrass Band, Blaine relates that “We played several West Coast tours, played some in Nashville, and played some festivals, but not a lot of festivals in the east.” The West Coast itineraries included performances at folk clubs, college auditoriums, and the Vancouver, British Columbia, Folk Festival. The one album that the group recorded, “Another Saturday Night,” was given “outstanding” and “highly recommended” ratings in a published review. Blaine and Butch Robins were cited for their contributions which “dominate the instrumental work with excellent lead, backup and rhythm. Additionally, they both get amazing tone from their instruments,” the reviewer wrote.

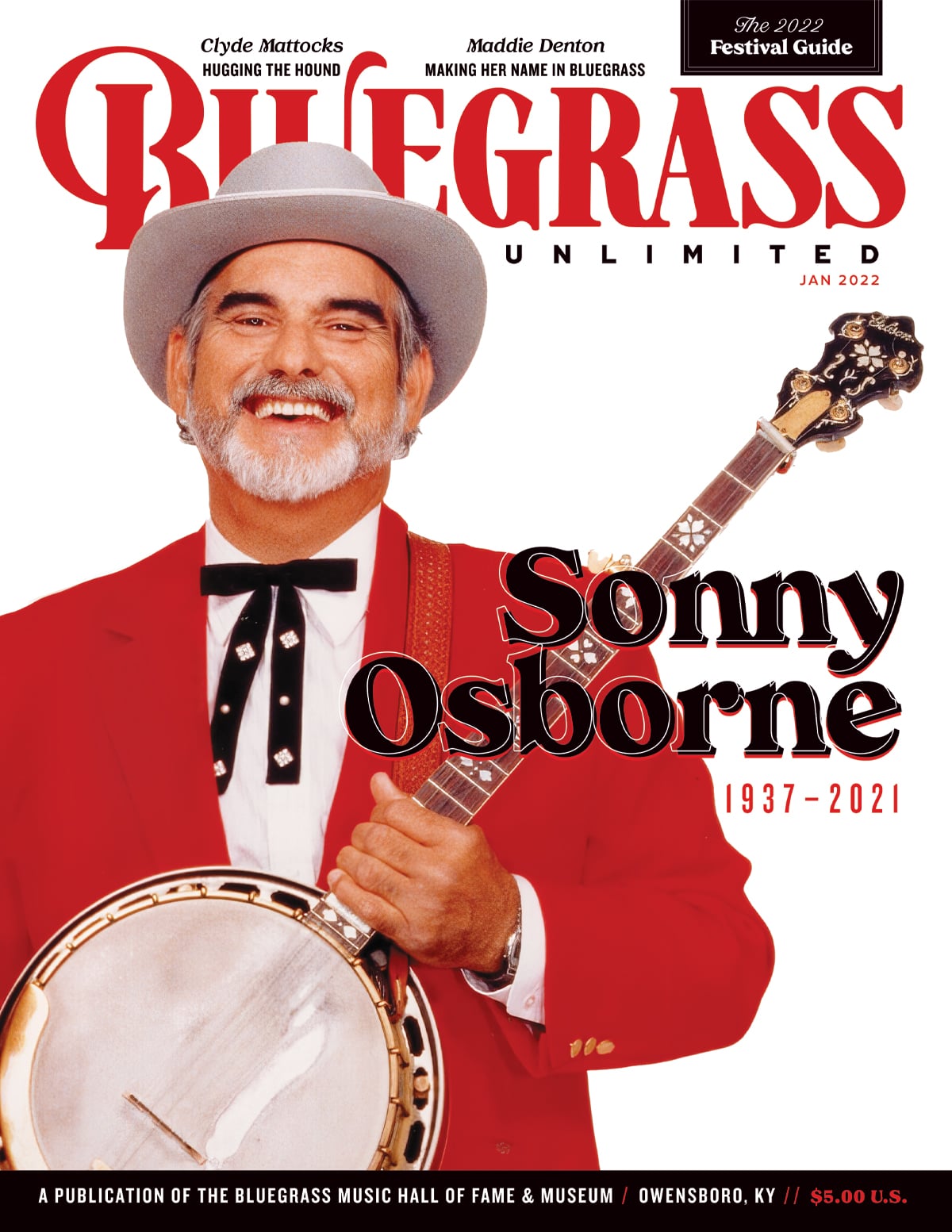

In the fall of 1982 Blaine was offered a job with the Osborne Brothers (BU, July, 1984), and since the offer came at a time when it appeared that the Bluegrass Band was soon going to “fall apart,” he accepted. “The position with the Osborne Brothers looked more stable than where I was,” Blaine muses. “And I was at a point in my life that I needed [stability] because I was more into thinking about starting a family and buying a house and all these real-life issues.” He was with the Osbornes longer than with any other group.

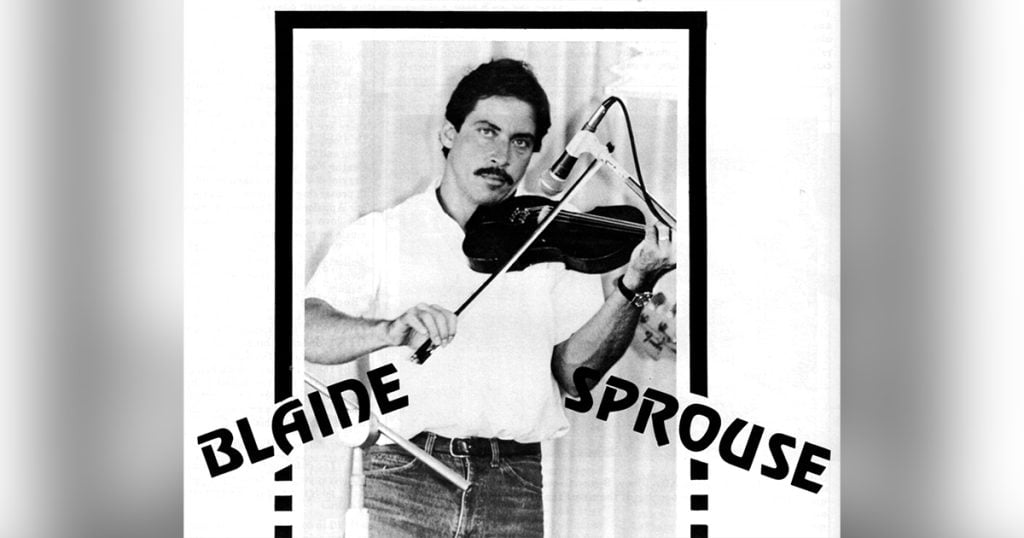

Blaine has recorded three solo albums, all of which have been on the Rounder label. Of the three, he is least satisfied with the first one, which was modestly and simply titled “Blaine Sprouse.” The reason, says Blaine, is “because I know how I felt when I was doing it. I was very nervous. I hadn’t been playing fiddle tunes per se. At that point I had been playing for almost two years with Charlie Louvin’s band. I hadn’t been playing up-tempo fiddle tunes. I didn’t feel like I was prepared at the time.” But, he philosophizes, the opportunity to record an album arose, and he didn’t feel like he could pass it up. At least one reviewer differed with Blaine in his opinion of the album. “There just ain’t no findin’ fault with this one—,” he wrote, “it’s an excellent instrumental fiddle LP.” In the album’s liner notes Kenny Baker writes that “to me, Blaine’s the most promising young fiddle player in the country.” In addition to having already played together informally for several years, Blaine and Baker had cut four albums together (one for Bill Monroe, one for the Osborne Brothers, and two of Baker’s) before Blaine made his solo recording debut. Also contributing to the liner notes was Bobby Osborne, who wrote that, “Blaine Sprouse in my opinion is one of the truly great fiddle players of our time.”

Blaine’s second solo album, “Summertime,” was recorded in 1981. Like the first one, it was produced by Butch Robins who, writing in the liner notes, called Blaine “the finest fiddler in bluegrass.” While tunes such as “Arkansas Traveler,” “Missouri Waltz,” and “Orange Blossom Special,” included on his first album would all be familiar to bluegrass aficionados, Blaine no doubt surprised a few of his fans with some of the tunes he selected for his second album. In addition to the Heyward/Gershwin folk opera tune from which the album gets its name, the listener will also hear Duke Ellington’s 1937 jazz piece, “Caravan,” and another Gershwin’ creation, “Oh, Lady, Be Good.” These are not typical bluegrass festival fare. But the boundaries of Blaine’s musical tastes are not narrowly defined. “I like all kinds of music,” he reveals, “if it’s tastefully done. I enjoy rock and roll, I love blues, I like jazz, [and] I love Irish and Scottish music.” And, he adds, “I enjoy listening to classical music, especially a chamber orchestra.”

Despite “Summertime’s” diversity, it contains enough orthodox material —“Jerusalem Ridge,” “Wheel Hoss,” and “Roanoke,” for example—to keep the bluegrass purists happy. The fact that a reviewer can write of the album, “I hear something in Blaine’s playing that I have heard before in Arthur Smith, Howdy Forrester, Chubby Wise, and yes, Kenny Baker,” speaks for its overall adherence to the bluegrass tradition.

“Brilliancy,” Blaine’s third solo album, which was produced by banjo virtuoso Bela Fleck, contains no unexpected titles. There are, however, a couple of arrangement innovations of note on the album. Edgar Meyer plays the bowed bass on two cuts, “Miss The Mississippi,” and “The Mist On The Moor,” and Blaine supplements his own fiddle work with a viola on “Miss The Mississippi.” The remainder of the selections display mainstream bluegrass instrumentation that demonstrates, as one critic put it, a . . highly polished technique—the best of both classical and contest stylings—while maintaining traditional fire and inventiveness …” of his three albums, Blaine tends to favor “Brilliancy” over the other two, although he finds the choice hard to make between it and “Summertime.”

Among Blaine’s other major recording efforts is a Rounder album titled “Snakes Alive” recorded by a group called the Dreadful Snakes. In addition to Blaine, the group consists of Jerry Douglas (Dobro), Pat Enright (rhythm guitar), Bela Fleck (banjo), Mark Hembree (bass), and Roland White (mandolin). The album, Blaine explains, “came about as sort of a jam session turned into a band. We used to jam at the Station Inn [in Nashville] quite a bit. Some tapes were made, and Rounder acquired one of them somehow and they were interested in making a record.” The album, a mixture of traditional and modern material, runs the gamut from such oldies as “Don’t Let Your Sweet Love Die” to “Story Of The Pharisee,” a gospel song written by Mark Hembree. Blaine is spotlighted in a rousing rendition of Bill Monroe’s “Brown County Breakdown.”

Blaine is only one of a handful of bluegrass artists who can be seen and heard on videocassette. A Central Sun Video Company production, “Two Fiddles, No Waiting” features Blaine and Kenny Baker backed up by a band composed of Bela Fleck (banjo), Alan O’Bryant (guitar), Sam Bush (mandolin), and Terry Smith (bass). An interesting presentation of two generations of top-flight fiddle talent, the cassette features a tasteful selection of tunes such as “Brandywine,” “Grassy Fiddle Blues,” and Blaine’s own composition, “Blue Ridge Reel.”

In addition to his debt to Kenny Baker, Blaine acknowledges the influence and inspiration of several other fiddlers, including Vassar Clements, Johnny Gimble, Howdy Forrester, and Mark O’Connor. He admires Clements’ playing because of his ability to play “off the top of his head. My perception,” Blaine says, “is that he doesn’t really think about what he’s going to play till he plays it. The major difference between Kenny Baker and Vassar Clements—this is my opinion—“he emphasizes,” [is that] Kenny Baker [will play] a certain break on [say] “Mule Skinner Blues” exactly the same way every time, which is really hard for someone like me to do. Yet Vassar Clements might play “Mule Skinner Blues” fifty times and never play it the same way twice.” One of the things Blaine likes about Howdy Forrester’s music is “his ability to write these tunes that are so monstrously hard to execute. He has written some of the technically hardest tunes for a fiddle player to play. They’re good tunes. They’re not just a montage of notes that are hard to get or hard to play. They’re really fine tunes. He cites as an example Forrester’s “High Level Hornpipe.”

What does Blaine strive for in his own playing? “I try to play tastefully—the right lick in the right place—and not play where I should not be playing. And not trying to play every lick that I know in one tune.” Blaine also makes a conscious effort to play with feeling. He says that when he’s playing backup to a singer he tries to complement the singer and make him or her sound as good as possible. He tries to play something that fits the singer’s style and the mood of the song. He guards against overpowering the singer.

Like all good musicians, Blaine is aware of the importance of his instrument and the necessary accessories—in his case the bow and strings. Of the four fiddles he owns, his favorite is one made by the French violin maker Honore Derazy who was born in 1794 and died in 1883. Derazy’s instruments have been described as substantially built and betraying the inspiration of Stradivarius and others of the Italian school of violin craftsmen. They are said to possess a remarkably powerful tone and a resonance that is becoming mellower with age. Blaine’s instrument, which has a scroll in the shape of an old man’s head and ornamental floral designs at the points, reflects the influence on Derazy of Jean Baptiste Vuillaume, a contemporary French luthier who had a penchant for making instruments with fanciful heads and other decorative features.

With respect to bows, Blaine prefers lighter sticks because, he says, they are easier to handle. The one he uses most of the time was made by Franz Albert Nurnberger, II, one of a family of some nine German bow makers whose lives spanned the period from 1793 to the middle of the twentieth century. Franz Albert, II, who was born in 1854 and died in 1931, has been called “one of the greatest German makers of bows, a consummate artist and master of his craft.”

On the subject of strings Blaine reports that “I’ve tried many different brands, and I always come back to the Dr. Thomastik with rope core.” These strings consist of a center bundle of braided steel strands surrounded by some type of metal winding. They are generally regarded as being more durable than strings with a gut core, more flexible than those with a solid steel core, and insensitive to changes in humidity. “I can’t keep gut strings in tune,” Blaine remarks, “and they don’t have the volume [of steel strings].”

Although music is important to Blaine, it does not totally dominate his life. He has a rather wide range of other interests. “I’m a voracious reader,” he intimates. “I’ve always read a lot, and I’ve been interested in so many different things—business, philosophy, psychology, communication skills.” He also likes horror novels, and is a devoted fan of novelist Stephen King.

Those who have paid close attention to Blaine’s on-stage fiddling may have noticed that his bowing arm is not that of a 97-pound weakling. He explains why. “I enjoy physical exercise. I enjoy running, playing a little tennis, pumping a little iron every now and then. I try to keep in shape a little bit. If I can keep my body in half-way decent shape, I hope it will serve me well for a good many years.”

Blaine makes his home in the Nashville area with his wife Mitzi and their pet dog, a Pomeranian. Mitzi, who plays a little banjo, is a registered nurse employed at a Nashville hospital. A native of Spruce Pine, North Carolina, she is related to the late composer and musician Scotty Wiseman (BU, March, 1986).

Blaine is not a musician who goes around giving out unsolicited advice, but if you ask him for suggestions that aspiring young fiddlers might do well to follow, he will tell you, “Have fun with it. Don’t get so caught up in trying to play something perfectly that you lose what I think music is basically all about—enjoying yourself while you’re doing it. I think you learn more when you’re having a good time. This is certainly true for me.”

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

I first saw Blaine with The Cluster Pluckers and wanted to see more. What an interesting gentleman. I only regret not being able to see more of his concerts. With little or no education it was always work but between work I tried to squeeze in as much music as possible. I love the fiddle and some years ago I remember waking to find my pillow wet with tears that came from a dream of playing the fiddle somewhere with other musicians. When I look at all the bands that Blaine played in, I’m sure that I was indeed at some of his shows. I used to follow Jim and Jesse when they lived in Prattville, Alabama. Jim Brock, Monroe Fields, and Allen Shelton. So many fond memories. Thank you Blaine for following thru with the heart.