Home > Articles > The Archives > Glen Duncan—A Fiddler’s Perspective: Thoughts On A Changing Industry

Glen Duncan—A Fiddler’s Perspective: Thoughts On A Changing Industry

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

July 1993, Volume 28, Number 1

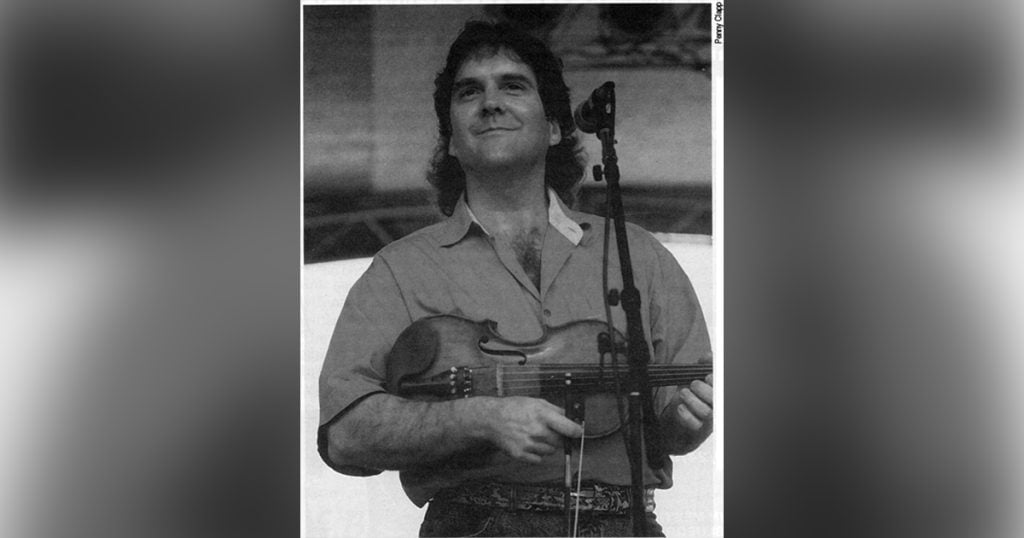

When Glen Duncan shares his views on the music industry, he speaks as a musician who has come full circle in the business that makes Nashville tick: music. As a child, he wanted nothing more than to become one of the “magic” musicians who created music in Nashville. Twenty years later Glen has found himself in Nashville as one of the most highly sought after fiddlers in the trade, balancing time between recording sessions and road gigs for country and bluegrass music’s grandest performers.

To say Glen Duncan has jumped around a bit as a sideman in various bands is to put it mildly. From Monroe to Mandrell, from Sparks to McEntire, his fiery fiddle has supported the sounds of country and bluegrass music’s grandest acts. The list of recording sessions goes far beyond, with everyone from Emmylou and the Oaks, to gospel’s famed Cathedrals and Heirloom. Currently Glen is also involved in producing a number of successful acts, a talent augmented by his tenure and full-circle perspective in the music business.

Glen’s history of band-jumping has been more a factor of scheduling and opportunity than what he was leaving at the time. When his session demand skyrocketed in about 1985, making the twenty mile trip to downtown Nashville from his Gallatin, Tenn., residence proved exponentially more lucrative and opportunistic than spending days away from home on a road trip as a sideman. Almost without realizing it, Glen had arrived at a career that somehow he knew he would eventually attain anyway. Even as a child, when parents and relatives questioned him for future “grown-up” plans, he would confidently answer, “session player.” And what exactly is a session player they would ask. Well, he didn’t really know, other than that there were these “magical” guys in Nashville who made records.

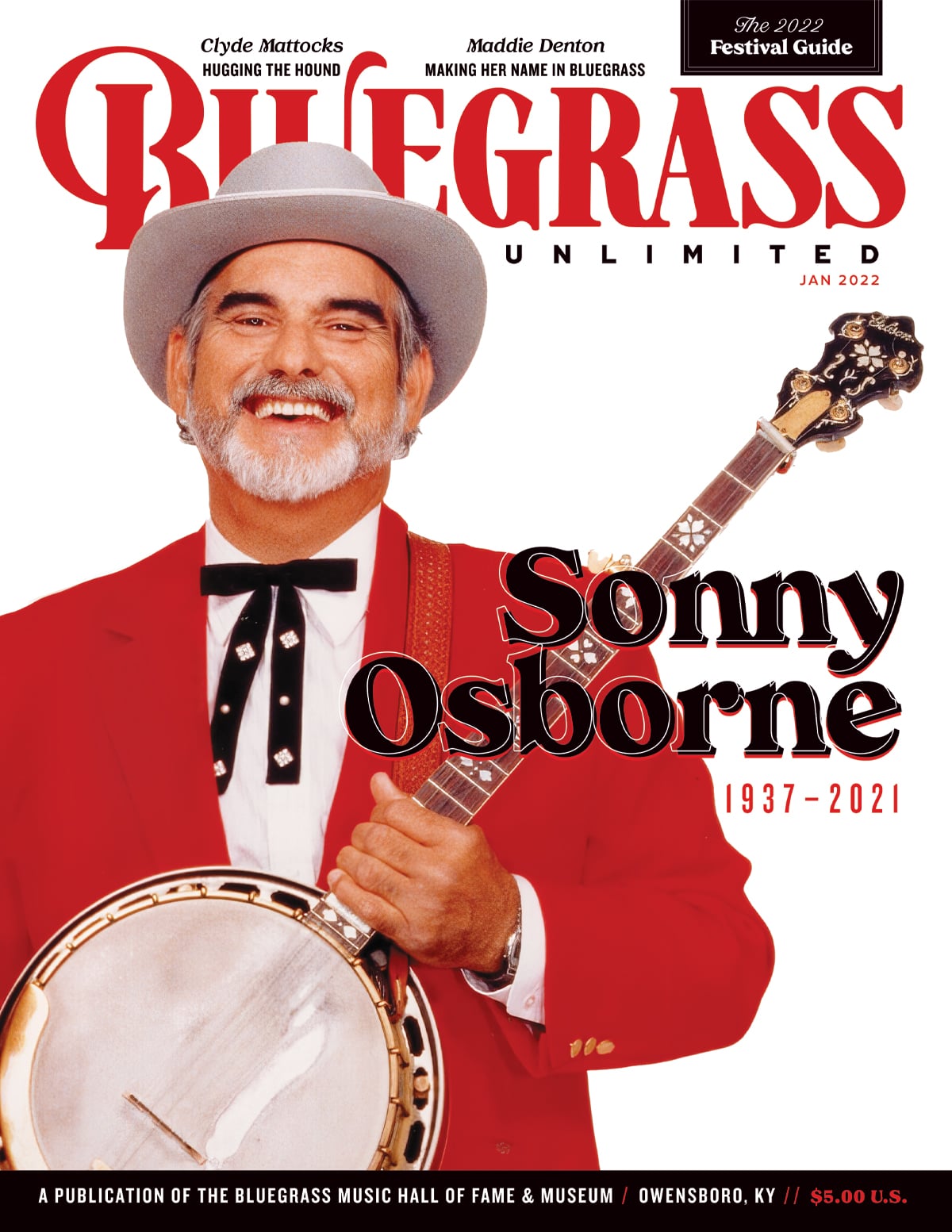

On Nashville’s hallowed Grand Ole Opry about twenty years ago were thriving bluegrass brother teams the Osborne Brothers and Jim and Jesse and, of course, Bill Monroe, all of whom would one day soon employ the young Columbus, Ind., fiddler. In the meantime, Glen was spending winter weekend evenings staring at a radio speaker in the living room of his parents’ home and “watching” the Opry with a religious fervor. “Staring at a radio is pretty incredible in itself!” smiles the 37-year-old Duncan. “All the static and distortion and then here’s all this music played just the way you want to play coming through a little speaker in your house!”

Like magic, the sounds of a country music show 240 miles away influenced the musical tastes of a young boy who wanted to play the fiddle more than anything. Ironically, it was not a fiddler who inspired him most, but rather the masterful five-string banjo sounds that Earl Scruggs was rapidly becoming famous for. Although Scruggs had already attained ultra-legendary status, it was not his, nor any musician’s characteristic fame that seemed most attractive. “I was simply attracted to people who really played their instrument well,” states Duncan matter-of-factly. After a short-lived fascination with the banjo at age ten, Glen began playing the fiddle in earnest when he was 16. Practicing six-plus hours every day and listening to his father’s inexhaustive collection of first generation bluegrass and traditional country music records, he literally lived the music.

By now his parents were taking occasional trips to Nashville and the old Ryman Auditorium and with Monroe’s Brown County Jamboree Park in Bean Blossom, just a short drive west of Columbus, he was already being exposed to the genre-forming bands of the era.

Glen’s method for mastering music is the advice he offers to anyone who wishes to do the same. Sitting on the edge of his bed, he learned all the breaks on all the records in his father’s collection. Not just Buddy Spicher’s. Not just Dale Potter’s either. But those of Vassar Clements, Red Taylor, Chubby Wise, Tommy Jackson, Jim Shumate, Johnny Gimble and Benny Martin as well. Glen’s theory is that a musician’s style is the sum of all that he has heard and learned.

Concern for sounding just like one of those stalwart aforementioned fiddlers has never worried him. He remembers when Monroe’s longest tenured musician Kenny Baker was the idle of throngs of young fiddlers. “Everybody was trying to sound just like Kenny Baker, but no matter how hard they tried, none sounded just like him!”

“I never set out to come up with my own style,” says Duncan, “but to be a good session player you need a certain amount of sensitivity and taste and it should compliment the song.” Though that may be easier stated than practiced, those seem to be the prominent characteristics of a successful session player. It goes without saying that a certain amount of technical expertise must underlay any successful musician. Tastefully applying that person’s talent for the betterment of a song might be the biggest factor separating the good musicians from the great.

It was not just the great fiddlers that influenced Duncan’s style. An avid steel guitar fan, Glen stayed awake nights as a kid studying Buddy Emmons, Hal Rugg and Lloyd Greene, three of the instruments’ masters and learning all their licks on the fiddle. Interjecting ideas from other great musicians on different instruments is a method Glen has used to keep a fresh and creative approach to the music. Glen won’t take total credit for this idea though. Much of Bill Monroe’s early mandolin sounds were heavily influenced by jazz and three- finger guitarists. Similarly, Jesse McReynolds wanted to recreate the sound of the banjo roll on the mandolin and ended up innovating a style of mandolin playing with his name attached to it.

Working with so many artists has given Glen a full-circle perspective of the acoustic music industry, from small scale festivals and community centers to the country’s largest venues. Not surprisingly, the crowds and venues Glen played on the country music circuit were considerably larger than those as a bluegrass sideman. And it’s somewhat ironic that one week he would pull his fiddle out of the case at a bluegrass festival and play to several hundred people and the next week use the same instrument, in basically the same style and perform for 20,000 fans at a large country music venue.

Whether or not most fans would like to see bluegrass music as commercially viable as country music, most would likely agree that there is a common desire to see the bluegrass music industry grow and prosper.

Glen’s diverse experience has afforded him the opportunity to see firsthand what media exposure can do for the popularity of an artist, and feels the same principles will work in bluegrass music as they do in country. “Media access is the best tool we’ve got,” explains Duncan. “If there is one thing that will help us all as an industry, it is media exposure.”

The media is exactly what sparked Glen’s interest in music to begin with and it came in the form of a small radio in his parents’ living room. The Grand Ole Opry was king and artists like Bill Monroe and Flatt & Scruggs knew it. “If you look at when bluegrass music really took off, it was the Grand Ole Opry clear-channel voice that put Monroe and Flatt & Scruggs into millions of households. The reason Monroe was so big was that he was a radio act in a radio age.” explains Glen.

If Bill Monroe made his greatest career strides in a radio age, then today must be the television age. The advent of Nashville’s Country Music Television (CMT) and The Nashville Network (TNN) has given incredible career boosts to young artists like Alison Krauss, Tim O’Brien and the Nashville Bluegrass Band. Long before the initiation of CMT and TNN, Flatt & Scruggs were getting a taste of what media exposure would do for their career when they began appearing on The Beverly Hillbillies program and providing music for Bonnie & Clyde. Bluegrass again took a quantum leap.

Glen feels that this media exposure is still the most important aspect that a young group should concentrate on. “Today, to break a new act, they must go into it knowing that we are living in a TV age and that is the audience they need to attract. There is no faster way to become a big successful act than to do well on national television and the best television outlets we have available now are CMT and TNN.”

With an artist performing to a combined 77 million viewers in North America alone via TNN and CMT, there exists a great deal of marketing power. “There is a whole lifestyle thing that is happening with people that watch and go to tapings of Nashville Now and buy records off TV,” explains Glen. “All we need to do is make the connection between what they want and what we do! I don’t think it’s a matter of selling them on something, I think it’s just a matter of making them aware of what we do. When an act goes on television, be yourself! Do what you do best! Don’t approach it like ‘Now we have to do something commercial for a TV audience,’ because people are hungry for sincerity.”

Monroe and Flatt & Scruggs communicated to their audiences with songs like “Cabin In Caroline” and “Little Cabin Home On The Hill,” singing to a generation of mountain people that were displaced from a way of life and being forced to move North to seek employment in factories. Glen feels that the same principle holds true today: relate to your audience with socially current and relevant topics. But what’s wrong with singing “Cabin In Caroline” today? “Nothing!” explains Glen, “It’s a great song in itself, but there are not many people today that were born in a log cabin.”

People today are dealing with topics like divorce, split families, job stress, AIDS and a host of other topics that were foreign to music fans forty years ago. Glen adds, “It’s the same alienation, that is people being torn from a familiar and comfortable aspect of their life, but as culture changes, lyrics need to change.” And as for the bluegrass music market, “Bluegrass has all the stylistic ingredients it needs to always make an impact. It’s not like a finite style that has reached its limit. There’s still a million formulas for success that haven’t been thought up yet.”

During Glen’s time working with Reba McEntire, he saw first hand how her songs related so personally with her audiences, particularly women who are forced to balance career and family responsibilities. “That’s why Reba has had the success that she’s had,” states Glen. “In most of her material, you can see a pattern of things that women can really relate to, especially in her videos.” Perhaps the bluegrass music circuit insulates us somewhat from the bigger music world, but in reality we are all competing for the same dollar. While some may argue that you must water down any true bluegrass before it can become commercially successful, Glen feels that with proper production, marketing and lyrical content bluegrass can stand firm in a market that seems sometimes impossible to crack.

The musician points to the recent success of Alison Krauss as an example. “The industry has come to her, but her style has not changed,” he says. “Alison’s music has heart and soul in it just like Ralph Stanley, just like Bill Monroe and I think it’s just so good. It comes down to sincerity…she believes in herself and I think people will buy from someone who believes in what they are doing. That is why George Jones will always be able to sell records, Ralph Stanley will always sell show tickets, because they believe in what they are singing and put that feeling across to the audience.”

If bluegrass carries with it some sort of Deliverance-era stigma, you couldn’t prove it by the programmers at CMT and TNN. Each of Krauss’s recent videos have seen considerable rotation, as have videos by John McEuen, New Tradition, Nashville Bluegrass Band and Tim O’Brien. “I don’t think a consumer comes home from work, turns on the TV, sees Alison and says, ‘Oh that’s bluegrass,’ I think he looks at it and says, ‘I like it,’ period!”

Maybe bluegrass music has in fact lost some of its folksy image among the general public, but what about Nashville’s powerhouse record-barons? “The record label people in Nashville are not sitting around thinking, ‘Oh, bluegrass is getting big, what can we do to stop it’ ” stresses Glen. “Anything that gets big, they will want. Anything that sells records, they want.”

The Nashville country music establishment has learned the power that exists when everyone gets behind and rallys to support a new artist. Glen draws the connection between the Country Music Association (CMA) and the International Bluegrass Music Association (IBMA). “When we see a real winner emerging, the best thing we can do is to get behind them 100%. That’s what the CMA does. The success of Garth Brooks wouldn’t have happened if people inside country music started undercutting him! They weren’t saying, Well you know, that’s not really country…that’s a Billy Joel song he has out!’ Who cares?! They were smart enough business people to realize that his success would help us all.”

It can be safely stated that country music really took off when the CMA got involved in earnest. Glen feels that organizations like IBMA and SPBGMA can influence bluegrass music just as dramatically. “I’m really impressed with what I see in the IBMA and SPBGMA,” he says. “It’s kind of like Nashville and Branson. You don’t have to like one and hate the other. You can like both and that’s just fine. It’s the same with these organizations: they all can help in different ways.”

As for the ways bluegrass music may change and experience growing pains with this increased popularity, “Nobody has to worry about losing the music they love,” explains Glen. “Flatt & Scruggs and the Stanley Brothers are on record. That’s bluegrass and it’s as good as it’s ever going to get. But, everything else that comes along is not a challenge to that, it’s just a new chapter. I think years from now we’ll look back at this time and say that’s when bluegrass really took off!”

As if predicting the growth of his own career, things are really starting to take off for Glen Duncan. The most exciting and anticipated project always seems to be the one he is currently involved in. He recently teamed with Nashville songster Larry Cordle to form Glen Duncan, Larry Cordle and Lonesome Standard Time (see companion article in this issue). With an album released on Sugar Hill, and a second one ready, there is plenty to look forward to. As close friends and musical cohorts, the partnership has created a musical magic that is fulfilling to Glen. “This project ties together many of the ideas that I feel are most important in recording music. I really believe in it,” concludes Glen.

From performing with some of the greatest legendary bluegrass pioneers to country music’s hottest young stars, Glen Duncan has found himself at the apex of the greatest players in country and bluegrass music. For a young fiddler who has already achieved so much, the future can only look bright…and it does.

Mike Drudge of Class Act Entertainment, a new talent agency representing the Lonesome River Band and Claire Lynch is a free lance writer and regular contributor to BLUEGRASS UNLIMITED and worked for the Grand Ole Opry’s Jim & Jesse Show for nearly four years.

Glen Duncan—Band History

1973-75 — Buck’s Stove & Range, Muncie, Ind.

1976 — Russell Brothers, Began Session work in Cincinnati

1977 — Boys From Indiana

1978 — Melvin Goins, Stoney Creek-Lexington, Ky.

1978-80 — Larry Sparks

1981 — Glen Duncan Band, Little Nashville Opry Band Leader, Nashville, Ind.

1982 — The Kendalls, Nashville, Tenn.

1985-86 — Bill Monroe

1986-87 — Jim & Jesse

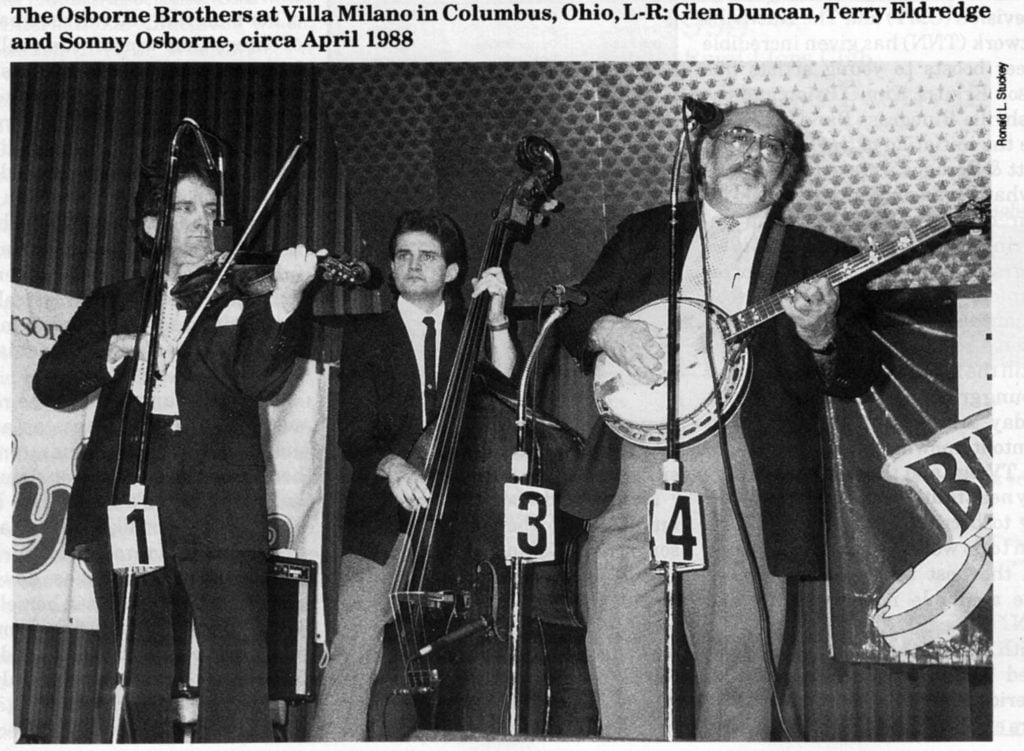

1987-88 — The Osborne Brothers

1988 — Barbara Mandrell

1988-89 — Reba McEntire

1990 — Full Time Session Player

1991 — Reba McEntire

1991 — Barbara Mandrell

1992 to date — Glen Duncan, Larry Cordle & Lonsome Standard Time

Abbreviated Session Discography

Country— Reba McEntire, Roy Rogers, Dolly Parton, Lorrie Morgan, Patty Loveless, Emmylou Harris, Eddie Rabbit, Rodney Crowell, Moe Bandy, Oak Ridge Boys, Randy Travis, Gatlin Brothers, George Jones, George Strait, Staler Brothers, Mark Chestnut, Lyle Lovett, Billy Hill

Bluegrass—Bill Monroe, Jim & Jesse, Osborne Brothers, Larry Sparks, Country Gentlemen, Doyle Lawson

Gospel—Heirloom, Cathedrals, Hensons, Lulu Roman, Barbara Fairchild

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Glen Duncan is legendary! Glen, Thank you for sharing your life on this earth playing music!