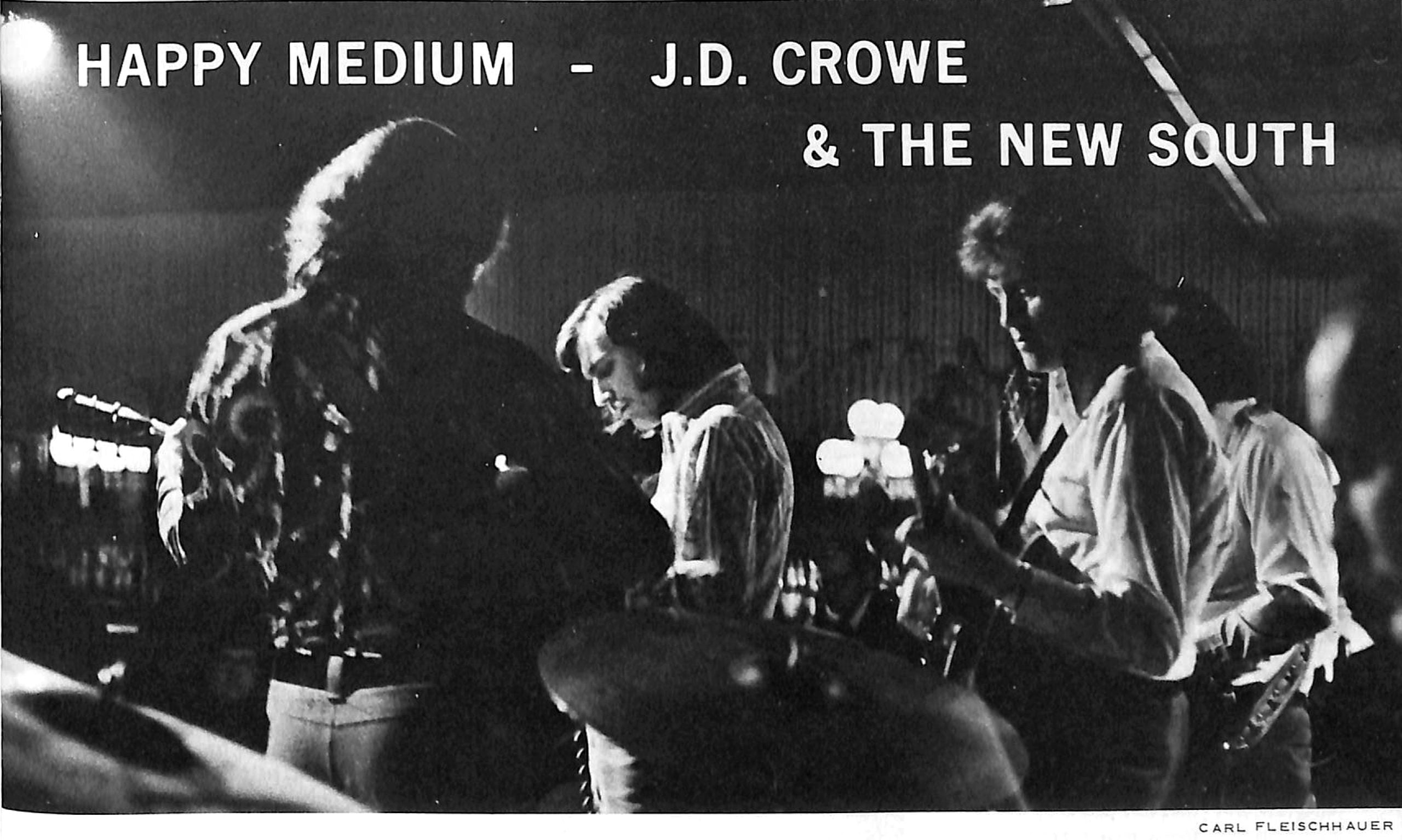

Home > Articles > The Archives > Happy Medium—J.C. Crowe & The New South

Happy Medium—J.C. Crowe & The New South

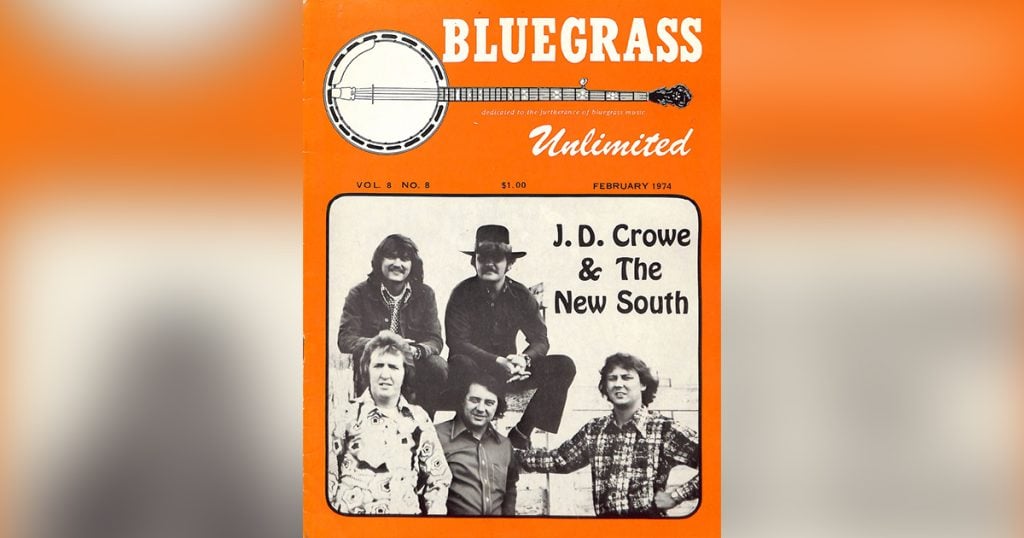

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

February, 1974—Volume 8, Number 8

“Right now, where would you get bluegrass records? Would you buy them in a rock store, or would you buy them in a country music store?” asks Tony Rice of J.D. Crowe and the New South.

“Both.”

“Right!” he continues. “You just don’t find bluegrass music stores! Bluegrass has either got to go country or get into rock, because it doesn’t seem like it’s going anywhere on its own. It just doesn’t seem to have enough push.”

Whether this prediction is right or wrong remains for history to determine, and for traditionalists and progressives to argue heatedly over in the meantime. But while the debate is raging, J.D. Crowe and his group are getting behind the bluegrass wagon and trying to give it the “push” they think it needs, in their own unique way.

Their resulting method of presenting bluegrass, contrasted with the traditional approach, might be described by drawing an anaolgy: Whether one serves consomme with sherry and lemon added, or ladles the broth straight from the pot, the basic ingredient remains the same. The appeal to the palate, however, depends on the tastes of the guests. J.D. and his group spice up their bluegrass with a thin slice of electricity and a shot of drums. Those purists accustomed to the unadulterated “old-timey” sound may reject the “tainted” product in favor of the “original” recipe. But those liberals already accustomed to drums and electricity in other forms of music, may like bluegrass better at first taste, if it is delicately flavored with these ingredients.

This is the principle from which J.D. Crowe and the New South, in catering to audiences with a variety of backgrounds, have developed their sound. In more than a score of years since J.D. started playing the banjo, he has witnessed the onslaught of rock, and has seen country music take the nation by a smaller storm. Both these forms of music are much louder than the soft, clear, acoustical bluegrass.

The fact that these have become more popular than bluegrass makes one wonder why. Doctors and scientists have noted that we are a society growing gradually deafer, thanks to the increasing noise level of our everyday urban environments. Perhaps, therefore, it takes greater decibel levels to stir peoples’ moods, emotions, and response centers, than unamplified bluegrass can offer tlie masses.

Whatever the reason for the success of rock and country music, J.D. has made an effort to pull enthusiasts from these arenas into the bluegrass realm, by luring them with elements common to the two “winners”. From both fields, therefore, the New South has borrowed electrification. It has also introduced drums. Further contributing to the country feeling is the well-developed earthy voice of lead singer Tony Rice. The ultimate result of this combination of ingredients is a form of electrified bluegrass with a heavy beat. All this is wrapped up in a potpourri of traditional and contemporary songs and tunes.

About two years ago the group moved into the electrification of its acoustical mandolin, bass, guitar, and banjo. They did this through the use of transducers, rather than through magnetic pickups standard in rock and country music. Essentially the transducer looks like merely a small block of wood, and is generally mounted either on top of the bridge next to the treble strings, or underneath the bridge on the inside of the instrument. In the wood is embedded an integrated circuit (a tiny chip with numberous electronic components). This circuit is attached to a wire leading ultimately to an amplifier.

Manufacturers explain the difference between the transducer, and the magnetic pickup this way: A transducer makes the sound loud while keeping it acoustically clean and pure, because it transmits the “energy from the vibration of the wood” rather than the “actual vibrations from the strings” as magnetic pickups do. All in the group except for J.D. use Barcus-Berry transducers. J.D.’s was specially designed for his 1937 Gibson Mastertone banjo by Wayne Clybirth of Cincinnati, Ohio.

Because it constitutes a form of electrification, the use of transducers has brought the band under considerable criticism – especially at festivals. “A lot of people think we’re trying to cut down bluegrass, but we’re not,” explains Tony Rice, who also plays guitar and M.C.’s. “Everybody in the band loves bluegrass more than anything else in the world.”

“To me bluegrass is hard-core bluegrass. But you can’t just keep doing the things that people have been doing for the last 20 or 30 years,” chimes in red-haired, freckle-faced James D. (“J.D.”) Crowe. “People are going to change.”

J.D. has in fact been doing these same “tilings that people have been doing for the last 20 or 30 years” for a good percentage of the 22 years that he has been playing banjo. It all started when he was about 13. He’d sneak off to the barn dance every Saturday night to spend the evening watching Earl Scruggs pick his 5-string.

To supplement this Saturday night staring, he’d run over to the radio studio with more eye-glue ready, to watch the maestro practice for two hours with his partner Lester Flatt, in preparation for their 15-minute radio program. “Anything I could catch, I was welcome to, but he couldn’t show me anything, because he just picked what he felt. When I started playing, there was nobody to give lessons.”

J. D. turned out to be a good “catcher”. A few years later Jimmy Martin was driving through Lexington, Kentucky with his car radio on, one Saturday night, and happened to hear a first-prize amateur-talent winner of about 16, plunking away over the air. Jimmy made his way to the studio, tracked down J. D. Crowe, and asked him to join his group, which J. D. did during his summer vacation from school. In 1955 J. D. rejoined Jimmy — this time for five years – until he left to form his own group. But he returned to help Jimmy on an album in 1966.

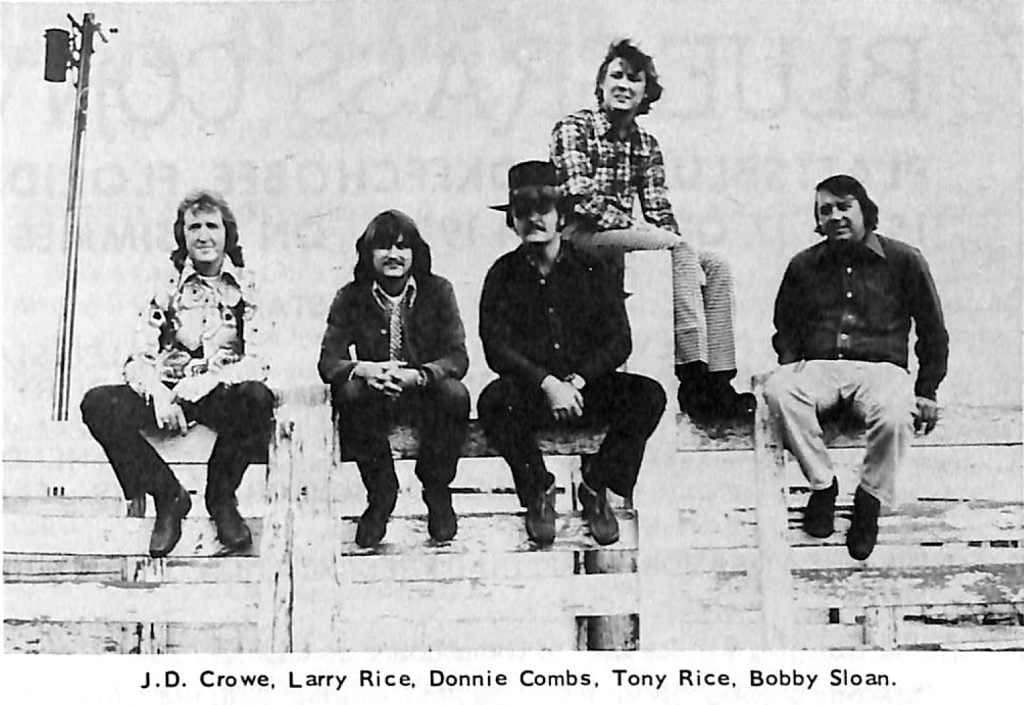

Other members of the New South have backgrounds as varied as the elements of which their sound is composed. Three of the remaining four have been steeped in a bluegrass that is somewhat more contemporary than J. D.’s. Two of these had close associations with Clarence White out in California. Bass player Bobby Sloan, who joined J. D.’s group in the early 60’s, came from a bluegrass band called the “Kentucky Colonels”, of which both Clarence and Roland White were members.

Tony Rice, who played with the Bluegrass Alliance before joining J. D., cites Clarence as the major bluegrass guitar influence in his life. Tony started playing the guitar at 5. When he was 9, he decided it was time to get acquainted with his hero. “I walked up to Clarence (then 16), who was playing in a band called “The Country Boys” at a country music show called Town Party, and said, ‘Hi! How ya going?’ Clarence taught me a little lead work, and from that point on, I was always in a race with Clarence.”

Larry Rice, Tony’s brother, was more specifically influenced in his mandolin style by John Duffey, co-founder of the Country Gentlemen, and now with the Seldom Scene in Washington. “I liked his style. It was jazzy rather than sticking to the tune.”

Only Donnie Combs, who throughout the performance of the New South sits behind the group subtly out of the forefront, his eyes shaded by a feather-banded modified derby-like hat, did not have his musical roots in bluegrass. Rather, his background is in rock and country music. He is the group’s second drummer, having joined a couple of years ago. He got into the business when his parents bought him a set of drums about 10 years ago to help him vent his frustrations. “I was an aggressive kid.”

Glancing over the backgrounds of the personnel in the New South makes one wonder why a group with influences as traditional as those acting on J. D. Crowe, and to a lesser extent on some of his musicians, would move away from the “original” sound in the first place.

Specifically, J. D. brought drums into his band to create a trompe- d’oreille (fool-the-ear) effect. “I like a big band sound. I don’t like to hear just two or three people … so I added drums to give our small bluegrass group a big bluegrass sound.”

But the drums also reflect J.D.’s philosophy of entertaining. “You have to bring out what you’re doing.” For this reason, the basic bluegrass instruments play minimally while the three singers (Tony and Larry Rice, and J. D.) are creating the harmony.

Instead, the bass speaks for the stringed instruments, for the most part, and the drums fill in on the beat and add variety. The process reverses itself somewhat during the instrumental breaks as the mandolin, banjo, and guitar move front and center to take the limelight.

Electrification was added, on one hand, for purely practical reasons. The group plays frequently at clubs during the winter. Any group that has ever played in a small club with people jabbering at tables right in front of them, at a level slightly above the surrounding uproar, know that at times it’s hard to hear one’s own music — not to mention that of others in the band. Putting the speakers behind you so you can hear yourself through the sound system encourages feedback. With transducers, J. D.’s group can put the monitor behind the performers so they can hear the music from their instruments, yet there is no feedback.

But an added benefit of this subtle electrification is the economic consequences. Tony Rice describes the situation this way: “As long as J. D. has played a 5-string banjo and tried to do it for a living and nearly starved . . . it’s much easier to take electrified instruments and get to the general public and feed your mouth than it is to play straight bluegrass instruments and go hungry.”

J. D. continues the thought: “I love Bill Monroe, Ralph Stanley, and Don Reno. I think the world of them I love their music, but I can’t make a living doing what they do, and I shouldn’t be condemned for it.”

J. D. Crowe’s group has instituted some unconventional changes in its bluegrass, for economic and practical as well as personal reasons, and has come under heavy criticism for it (even to the point of being scratched off the invitation lists of some festivals they used to play at). Nevertheless, any group that can sell bluegrass to the masses ultimately brings in business for the traditionalists as well as giving the whole bluegrass movement a little push. For a certain percentage of the catchers-on are bound to get really hooked on the sound, and in the process of snatching up records and seeking out performers, to follow it all the way back to its traditional origins.

Amid all the criticism, however, one wonders ultimately not why J. D. has brought traces of rock and country music into his sound, but rather why he continues to stay in bluegrass. The answer is simple. He and the New South love the music and want it to become known as a form of music in its own right.

But Tony Rice has an additional whimsical reason that perhaps answers this question as well as any could: “If you go rock, you have to let your hair grow down to the floor, and if you go country, you have to cut it all off. Right now we like our hair just about happy medium.”

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

I find it relevant that their monumental, breakthrough ‘The New South’ Rounder lp in early 1975 included no electrified instrumentation and no drums. The magic sauce was created by adding Ricky Skaggs and Jerry Douglas to the band.