Home > Articles > Special Series > Bill Emerson—Staying Home in the Washington, D.C. Area (1966-1970)

Bill Emerson—Staying Home in the Washington, D.C. Area (1966-1970)

After playing on the road with Jimmy Martin off-and-on for five years, Bill Emerson decided that he had had enough of the intense road travel. He still wanted to play music, but he did not want to be out on the road quite as much as being a member of Jimmy Martin and the Sunny Mountain Boys demanded. In 1966, he reunited with Washington, D.C. area musicians and began performing in area clubs and working in various recording sessions. Although he was staying closer to home, and working a few odd jobs on the side, Bill wasn’t going to give up playing the banjo all together.

Don Bryant was a Washington, D.C. area banjo player who played with numerous area bands such as Bennie and Vallie Cain, Buzz Busby, Bill Harrell, and he even filled in for Earl Scruggs after Earl’s 1955 car accident. Bryant had given up a professional career in music to become a Washington, D.C. police officer and tells this story about Emerson’s love for the music. Bryant said, “Bill Emerson and I were close friends beginning in the mid 50’s. Toward the end of his life we were emailing about weekly. I have one memory of something he said to me that stands out. He and I were talking one day shortly after I had completed my military commitment and had joined the D.C. police department. I obviously had no intention to ever go back to being a full-time professional banjo player. I remember he said to me—and it told me how dedicated he was—he said, “I don’t understand how you can walk away from having a life playing banjo for a living.”

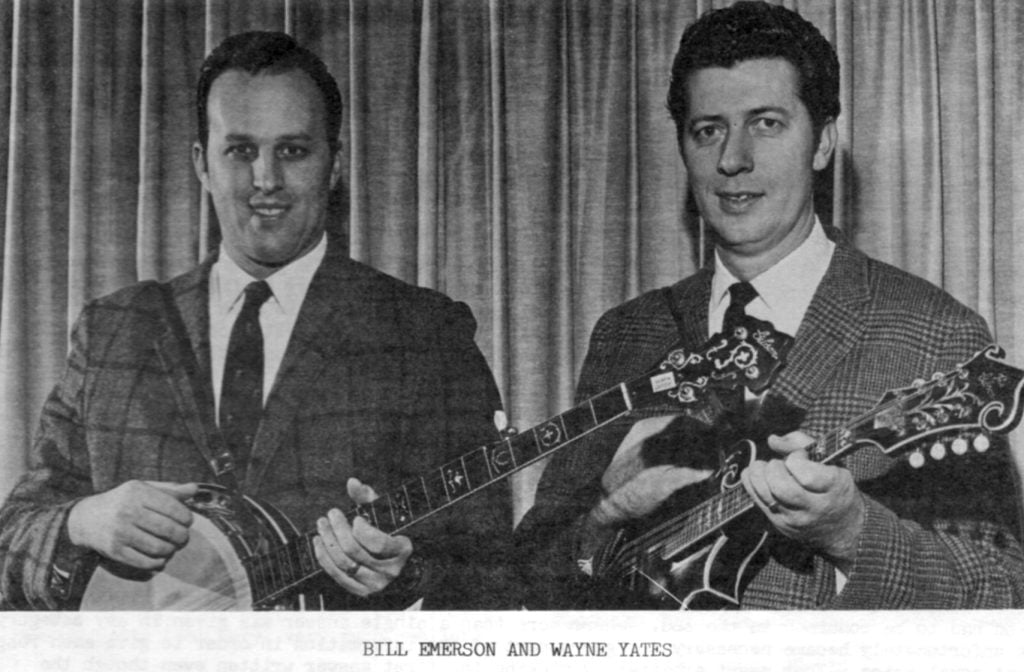

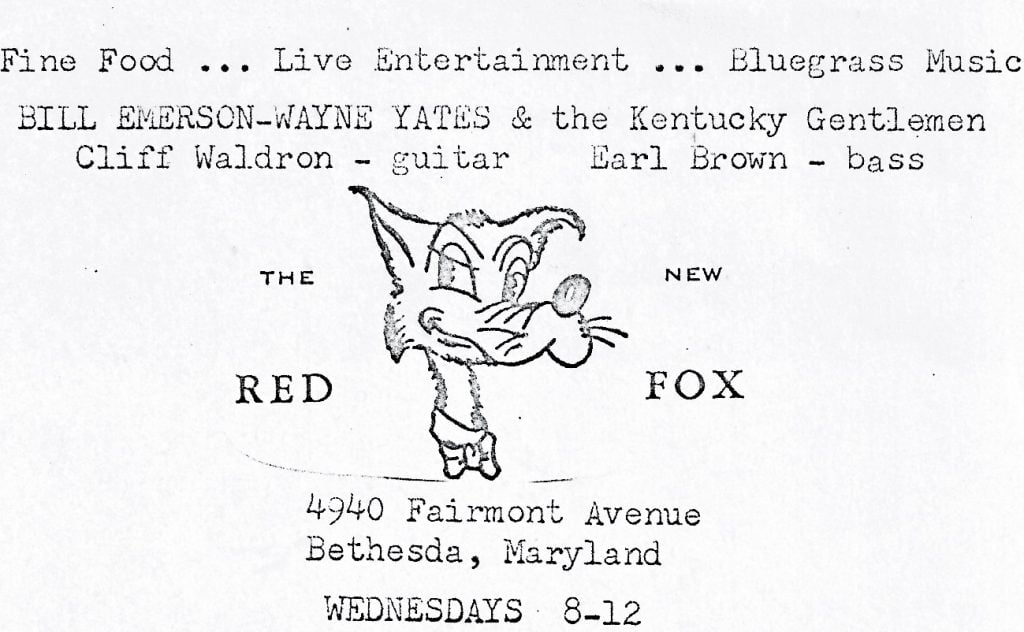

After leaving Jimmy Martin for the second time, Emerson returned to playing with Wayne Yates, with various other band members (such as Buzz Busby, Earl Brown, and Cliff Waldron) performing as the Kentucky Gentlemen and, later, the Lee Highway Boys.

Emerson’s relationship with Wayne and Bill Yates began in about 1960 when he performed with the brothers—plus Ferrell Brown on guitar—as The Yates Brothers and the Clinch Mountain Ramblers. When Emerson left the band to play with Jimmy Martin, Smiley Hobbs replaced him on banjo. Ferrell Brown also left the band and was replaced by Bill Harrell on guitar and Buck Ryan joined to play fiddle.

In 1963, when Bill Emerson left Jimmy Martin the first time, he returned home to play with the Yates Brothers once again. By this time Bill Harrell had left the band and Red Allen was playing guitar. This configuration called themselves Red Allen and the Kentuckians. They performed at the Shamrock in Washington, D.C. and traveled widely performing at venues such as the WWVA Jamboree in Wheeling, West Virginia and the Old Dominion Barn Dance in Richmond, Virginia. In 1964 that band broke up. Wayne had become tired of life on the road and Bill Emerson and Bill Yates went to work with Jimmy Martin.

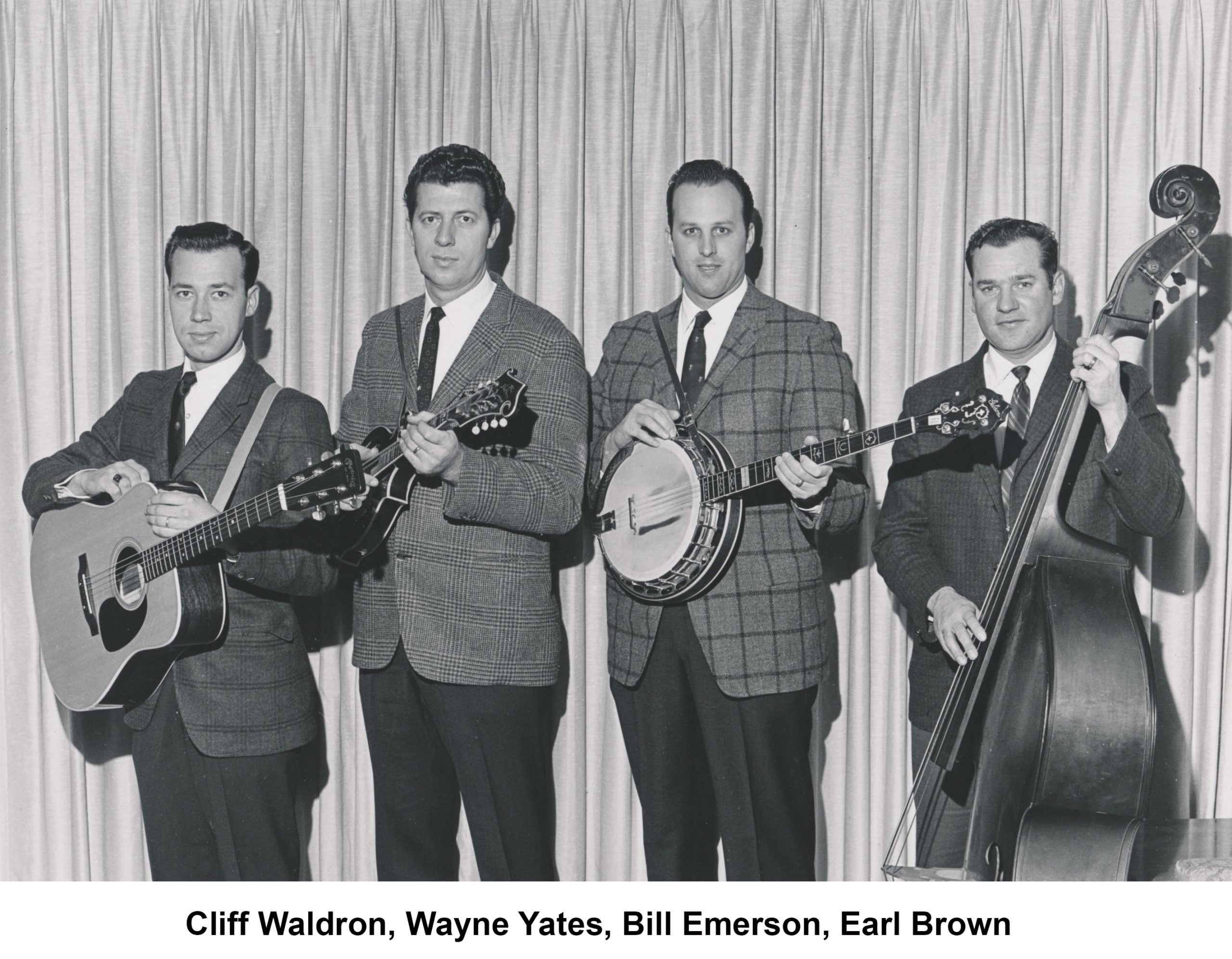

When Bill teamed up with Wayne Yates in 1966 the band consisted of Emerson (banjo), Yates (mandolin), Buzz Busby (guitar), and Earl Brown (bass). When Busby left the band, Cliff Waldron was hired to play the guitar. In an interview conducted for the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame and Museum’s Oral History Project, Emerson remembers that when he called Waldron to offer him the job, Waldron was playing the mandolin. Waldron responded to Emerson’s job offer by asking “Should I bring my mandolin?” Emerson responded that Wayne was playing the mandolin and asked Waldron if he played the guitar. Waldron said, “I’m not much of a guitar player, but I can try.”

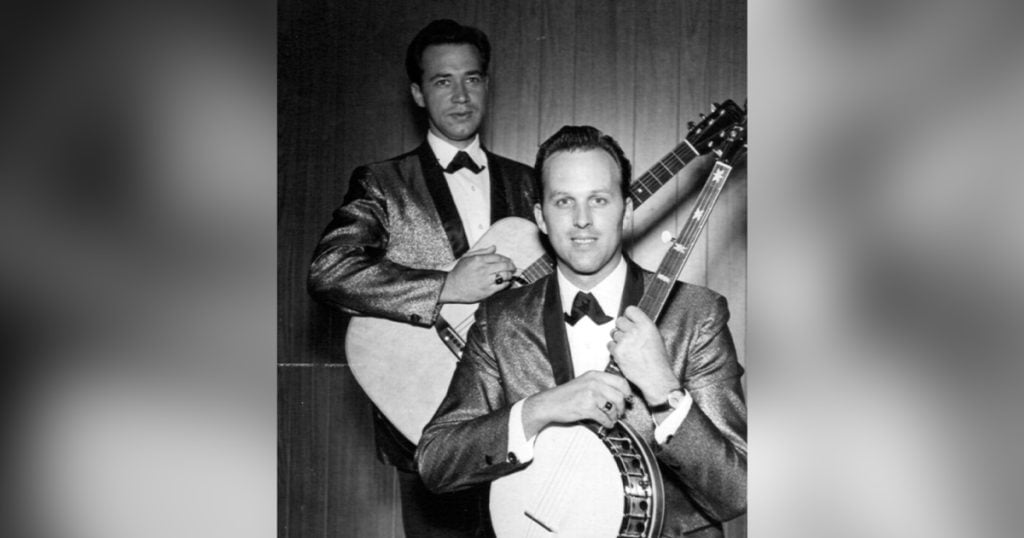

Emerson and Waldron

When asked about how he ended up playing with Emerson and Yates, Cliff Waldron—in a phone interview in December of 2021—said, “I was playing mandolin with the Page Valley Boys and Bill gave me a call because Buzz couldn’t make a show and he was looking for a replacement. He wanted the phone number of our guitar player, Don Lambert. I gave him Don’s number and then a little while later Bill called me back because Don wasn’t answering his phone. This was before the days of answering machines. He asked me if I could fill in and I told him that I played some guitar around the house, but I’d never played guitar in a band, only mandolin. Bill asked if I could come that night. I said, ‘I’ll try, but I don’t know how I’ll do.’ He told me it was just a show in a noisy bar, so he thought it would be OK. I had a Gibson J-45 guitar and I took that to the show.

“During the break that night we were back in the kitchen and Bill said, ‘Where did you learn how to play the guitar like that?’ I told him that it was just the way I played guitar. He said, ‘What you are doing fits my banjo. Do you want a job?’ So, I joined the band and after we’d played together for a while Dick Freeland from Rebel Records came in and I saw him talking at a table with Bill and Wayne. I didn’t know him, but they did. Dick told them that if they could get some new songs together that he would like to record the group. As time went on, Wayne lost interest and Bill said to me, ‘You and me could do it.’ I was working as a barber at the time and had Mondays off. Bill and I would get together every Monday and work on new songs.”

When asked how he first met Bill Emerson, Waldron said, “Bill was working painting apartments with Wayne Yates. I had a cousin, named Reese, who was working with the same contractor. He loved bluegrass and would go around and watch Bill Emerson and Wayne Yates play with Bill Yates and Ferrell Brown. He invited me to come out one night and he introduced me to them and told them that I played mandolin. They invited me up on stage that night and I sang a couple of songs with them.”

When Emerson and Waldron teamed up, in late 1966, they were interested in doing something different—something that gave the band their own identity. Emerson had learned—during this time with Buzz Busby and working with John Duffey in the early Country Gentlemen—that in order to stand out you couldn’t just do the same thing that everyone else was doing. In a 1992 Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine interview, Emerson said, “I wanted to do something a little different. I had the idea of doing tunes like Johnny Rivers’ recording of ‘If I Was A Carpenter’ or Manfred Mann’s tune, ‘Fox On The Run.’ We still wanted to do some straight-ahead bluegrass music but wanted to look and sound a little different. We didn’t want to be just another straight-ahead bluegrass band. Therefore, our music attracted a wider, younger and more sophisticated audience. It paid off.”

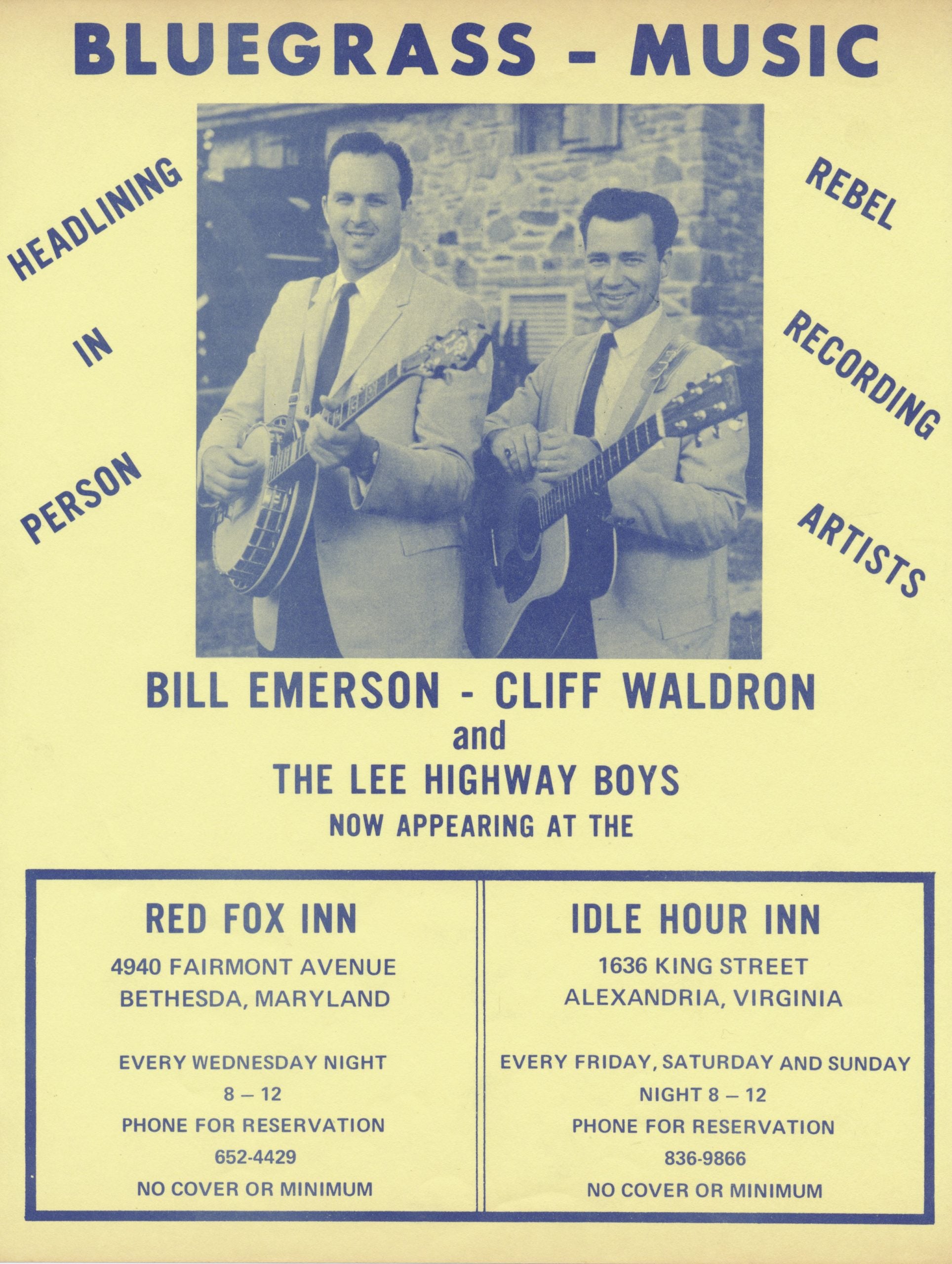

The liner notes to a Rebel Records release of The Best of Emerson and Waldron (written by George B. McCeney in 1997) explained the group’s beginning this way, “By 1966 Bill Emerson had indeed found himself playing with Buzz Busby, but soon thereafter Buzz Busby left the group, prompting Emerson to contact a local mandolin player from the Page Valley Boys named Cliff Waldron. Curiously, Cliff Waldron had to become a guitar player to replace Buzz Busby, a mandolin player who had switched to the guitar. An ad in Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine convinced a fiddle player from Jefferson, Maryland, Bill Poffinberger, to join this reorganizing group and it remained only to add a single musician to replace the departing mandolin player, Garland Alderman. Ed Ferris continued to play bass.

“During this period of personnel adjustments in late 1967 and early 1968 the band moved to a regular venue in Bethesda, Maryland, The Red Fox, where Bill Emerson and Cliff Waldron became official partners. Charles R. “Dick” Freeland, the founder of Rebel Records, became interested in capturing the potential of this new band, and with the help of local musicians like John Duffey, Billy Baker, Tom Gray, and Ed Ferris produced the first Emerson and Waldron LP, New Shades Of Grass.”

New Shades of Grass was recorded and released by Rebel records in 1968. The tunes that appear on that album include the aforementioned “If I Were A Carpenter,” plus three Emerson and Waldron originals—“I’m Bound To Ride” “A Message For Peace,” and “You Didn’t Say Goodbye.” Additionally there were several instrumental tunes credited to Emerson—“Indian Hill,” “Red Wings” “Wildwood Hoedown,” “Fast Freight,” “Snow Buck,” and “Little Nellie Grey.” The album also included a Carter Stanley tune “Our Darling’s Gone,” and “The Snake” by Oscar Brown, Jr.

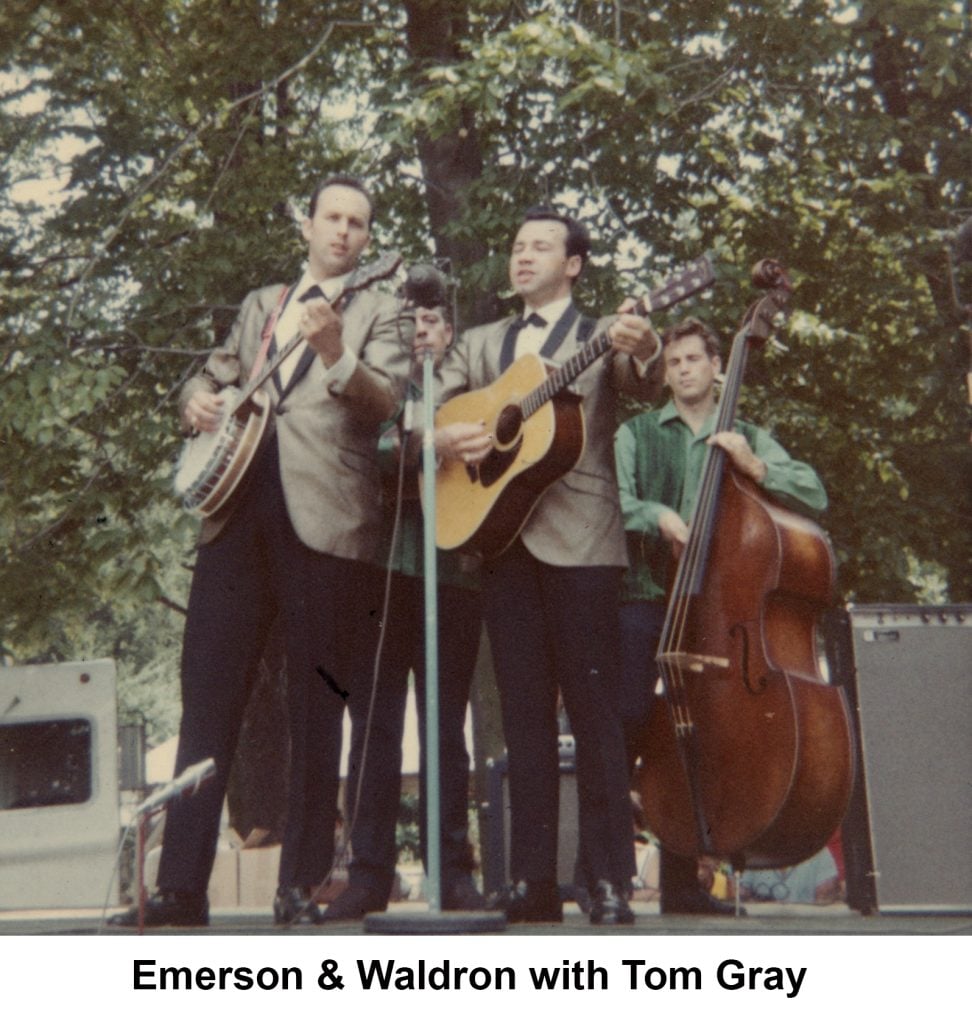

After Emerson and Waldron’s first recording, they continued to perform at The Red Fox in Bethesda, Maryland and one night a group of musicians who had been jamming nearby in Ben Eldridge’s basement came by the club and performed during Emerson and Waldron’s breaks. This group included Ben Eldridge, Mike and Dave Auldridge, and John Starling. After hearing Mike Auldridge perform, Bill Emerson recognized the potential of adding the Dobro to the Emerson and Waldron sound and they invited Auldridge the join the band that night.

With Auldridge now in the band, they returned to the studio to record their second album, Bluegrass Country, in 1969. The musicians on these sessions included Bill Emerson (banjo and tenor vocal), Cliff Waldron (guitar and lead vocal), John Duffey (mandolin), Ed Ferris (bass), Bill Poffinberger (fiddle), and Mike Auldridge (Dobro and baritone vocal). The tunes that the band recorded for this album included the vocal tunes “Proud Mary,” “Lonesome Night,” “Midnight Special,” “All the Good Times,” “Fox On The Run,” “Little Log Cabin,” and “Twenty-One Years,” and the instrumentals “Runnin’ South,” “Trouble Among The Yearlings,” “Faded Love,” and “Maiden’s Prayer.”

This was the first time that a bluegrass band had recorded Manfred Mann’s “Fox On The Run,” which has been covered by many bands since. Bill Emerson was the one who brought this tune to the group. After Emerson passed away in August of 2021, his son, Mike, was organizing Bill’s belongings and found the 45 rpm record of Manfred Mann’s recording of “Fox On The Run” that Bill had used to learn the song. Tom Gray, who was playing bass for the band when Emerson first suggested they learn the tune, said that the first time that they played it was at a party in the basement of his home.

Early in 1970 the same group of musicians went back into the studio and recorded a third Emerson and Waldron album titled Emerson and Waldron Invite You To A Bluegrass Session, released by Rebel in August of 1970. The vocal songs recorded for this album were “Early Morning Rain,” “Who Will Sing For Me,” “The Water’s So Cold,” “Lodi,” “A Face From Another Place,” “Mama’s Hungry Eyes,” “Break My Mind,” and “I Feel Lonesome Too,” The instrumentals tunes on this album were “Downtown Blues,” “Home Sweet Home,” “Spanish Grass,” and “Laura’s Tune.”

A few other tunes were cut on this session, but did not appear on the recording. However, Rebel did release them later, in 1997, when the album The Best of Emerson and Waldron was released. These tunes included “Wheels,” “There Is No Room In My Heart For The Blues,” “Shiloh,” and “I Know You Are Married.”

The Emerson and Waldron group became well known for being one of the first bands to include bluegrass versions of rock, pop, and country tunes on the set list and their recordings. In the 1992 Bluegrass Unlimited article, Emerson was asked if he felt that the band had something to do with the development of “newgrass.” Emerson said, “Yes, I feel that way. We were doing that before anybody else. The only other band you could compare to it was the Country Gentlemen with their folk music approach. We didn’t really get into newgrass. It was more the material than the instrumental approach because I’m just not a newgrass banjo player. But, I think we paved the way to a certain extent in that the material we were doing lent itself to that kind of thing. First thing you know, the Bluegrass Alliance came along and, to me, they were the pioneer newgrass group. They were also doing songs like ‘Fox On The Run’ and they did newgrass a lot better than we could. Nevertheless, I feel that we broke ground before them to a certain extent.”

Teaching Banjo Lessons

In addition to performing and recording with Emerson & Waldron, Emerson also started teaching banjo lessons at Arlington Music and Gordon Keller Music. John Duffey was the instrument repairman at Arlington Music and Duffey’s wife, Nancy, was the manager. The store had individual teaching rooms downstairs. Bill taught half-hour long lessons at Arlington Music for a couple of years and had up to 30 students. Buster Sexton, who would later go on to play some fill-in dates with the Country Gentlemen, Buzz Busby, Red Allen and the McPeak Brothers, and was a member of Wayne Yates and Company and, later, Patent Pending, (and is the father of fiddle player Chris Sexton of Nothin’ Fancy) was one of Emerson’s banjo students.

In a phone conversation with Buster Sexton in December 2021, Buster talked about learning to play the banjo from Emerson. He said, “I had spent a few months trying to learn the banjo on my own and then went to the Indian Springs Bluegrass Festival. I picked up a copy of Banjo Newsletter and there was an advertisement for private banjo lessons with Bill Emerson. The ad said that the lessons were for intermediate and advance players only. I called and set up a lesson time and when I went to the lesson he found out that I couldn’t play. I asked him to give me a chance. He showed me some rolls and chords and said, ‘Let’s see what you can do by next Saturday.’ I was so determined that I went home and practiced what he showed me and called him on the phone that same night and played it for him.” Bill then accepted Buster as a student.

Buster said that Bill’s approach to teaching him was to first develop a foundation by learning rolls and chords and how they worked together. From there he learned to play simple songs, like “Cripple Creek,” and then added more Scruggs style techniques and songs. After that, Emerson taught him some of the tunes that Bill had written. Sexton said, “Bill was my mentor and over the years became a good friend. He called me in 2014 to play a couple of shows on the guitar with his band Sweet Dixie. The thought struck me, ‘I’ve come full circle with Bill Emerson.’”

Sexton printed and framed an email message that Bill Emerson had sent him years after Sexton had studied banjo with Emerson and he hung it on the wall in his home. In the email Emerson told Buster that he had the most “fire” and “desire” and the “real ‘want to’” than any other student that Bill had taught. In the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame and Museum interview Bill mentioned that in order to learn how to play the bluegrass banjo he felt like the student had to have a real burning desire to learn. When talking about his days of teaching the banjo in that interview, the only student he mentioned by name was Buster Sexton.

Other Studio Work

The first recording that Emerson worked on after leaving Jimmy Martin was with Scotty Stoneman in February of 1967 at Unity Recording Studio in Washington, D.C. for Stoneman’s album titled Scotty Stoneman Mr. Country Fiddler. In addition to Stoneman on fiddle and Emerson playing the banjo, Charlie Waller played the guitar and Tom Gray played bass.

Late in 1967, Emerson also went into a farmhouse owned by Tracy Schwarz’s in Glenrock, Pennsylvania to record with Del McCoury for Del’s Arhoolie release Del McCoury Sings Bluegrass. Chris Strachwitz, with Arhoolie Records had brought a portable tape recorder in order to facilitate some field recordings. In addition to McCoury and Emerson, the musicians on this session included Wayne Yates (mandolin), Billy Baker (fiddle) and Tommy Neal and Dewey Renfro alternating on bass. Regarding this session—in an article that appeared in Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine in March of 1992—Emerson said, “We did that album in one afternoon.”

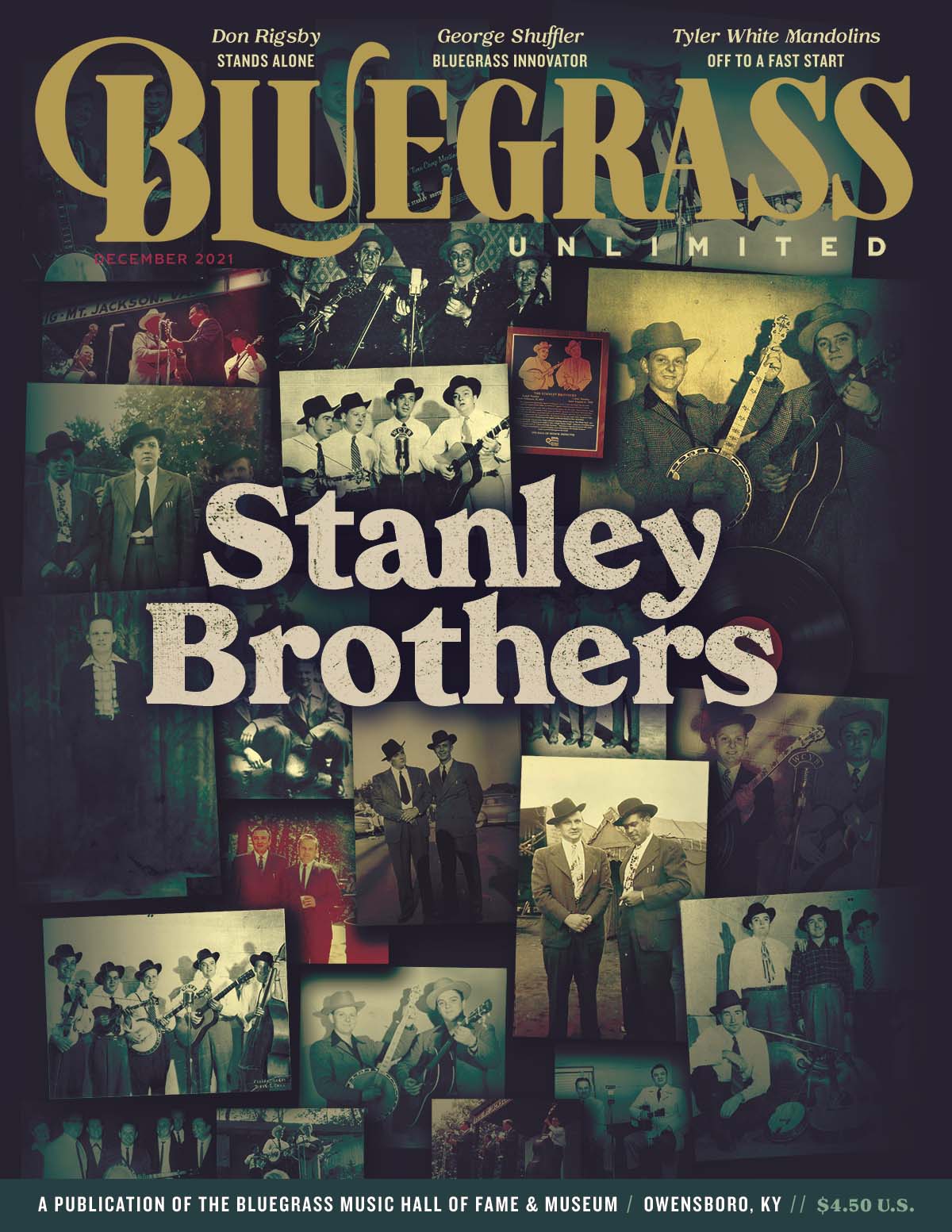

Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine was founded in 1966 by a group of Washington, DC area bluegrass musicians and fans. One of the founders, Dianne Sims, had found out—after the fact—that the Stanley Brothers had been performing in town. She called bluegrass friend Gary Henderson and asked if he had been aware of their performance. He had not. She called another bluegrass friend, Pete Kuykendall, and asked if he had known about it. He had not. Vowing not to miss another such local performance by a touring bluegrass band, the three decided to start a Washington, DC area bluegrass newsletter.

Along with friends Dick Spotswood, Dick Freeland, George McCeney, and Vince Sims, the aforementioned three friends launched Bluegrass Unlimited in July of 1966. Dick Spottswood came up with the name Bluegrass Unlimited based on a magazine called Blues Unlimited that was published in England. Dianne and Vince Sims procured a government surplus mimeograph machine and set it up in their basement. They hosted monthly parties for the purpose of printing and assembling the publication. It was a completely volunteer operation. Some of the volunteers included: Tom and Sally Gray, Mike and Dave Auldridge, John Duffey, Joan Shagan, Pete and Marion Kuykendall, and Alice Gerrard.

Bill Emerson and his wife and Lola were also involved in the magazine in its early years. They would attend the monthly parties—which usually involved a bit of playing music along with printing and assembling the magazine. Bill also wrote articles for the magazine in the early years and Lola sold advertising space.

The End of Emerson and Waldron

In 1970, Eddie Adcock—who was playing banjo for the Country Gentlemen—could not make a show at Oberlin College in Ohio and the band called Bill Emerson to see if he could fill in. The band consisted of Emerson (banjo), Charlie Waller (guitar), Bill Yates (bass), and Jimmy Gaudreau (mandolin). The show went so well that after it was over Waller told Emerson that Adcock was leaving the band and he asked Emerson if he wanted the job.

Although Emerson and Waldron were experiencing success, they were not as well-known as the Country Gentlemen. The Country Gentlemen offered to make Emerson an equal partner in the band and thus the pay was better. So, Emerson accepted the job in May of 1970. In the Oral Histories interview Bill said, “They made me an offer I couldn’t refuse.”

After Bill Emerson left the band, Cliff Waldron moved to Roanoke for a short while to play with the Shenandoah Valley Cut-ups. The band was performing at a festival in Berryville, Virginia one weekend where Bill Monroe was also performing. Cliff Waldron remembers that Bill approached him that weekend and said, “Why are you playing with those guys? You should have your own band. If you go out on your own and you need any help, you call me and I’ll do what I can for you.” Cliff took Monroe’s advice and started Cliff Waldron and the New Shades of Grass with Ben Eldridge (banjo), Mike Auldridge (Dobro), Ed Ferris (bass), Bill Poffinberger (fiddle), and Dave Auldridge (rhythm guitar).

When asked about Bill Emerson leaving the group to re-join the Country Gentlemen, Cliff Waldron said, “Bill saw an opportunity to make a little more money and he took it. I understood that and we always remained friends. When we met, I was just a redneck country boy and he helped me get started. I have always appreciated that.”

In the next installment of this article series, we will address the years that Bill spent with the Country Gentlemen (1970-1973) before joining the U.S. Navy and becoming a member of Country Current.

Share this article

2 Comments

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

With regard to Scotty Stoneman’s /Mr Country Fiddler/ LP – Dennis Satterlee, in his book /Teardrops in my eyes: the music of Harley ‘Red’ Allen/ (2007), pp 83-4, dates the recording session ‘c. 1965 or 1966’ at the Ben Adelman studio, and gives the personnel as Scotty Stoneman (fiddle), Red Allen (guitar), Wayne Yates (mandolin), Dick Drevo (banjo), and Bill Yates (bass). Satterlee quotes accounts from Drevo (a recording studio owner and a banjo player who learned licks from Bill Emerson) and Wayne Yates.

This is just a comment, not a criticism; I’m enjoying this important series greatly.

Excellent article. I suggest another reason Bill may have diverged from Jimmy Martin – he had his own ideas regarding music and wished to explore them. Certainly his work with Cliff Waldron took bluegrass in some new directions. I’m thankful he *was* adventurous.