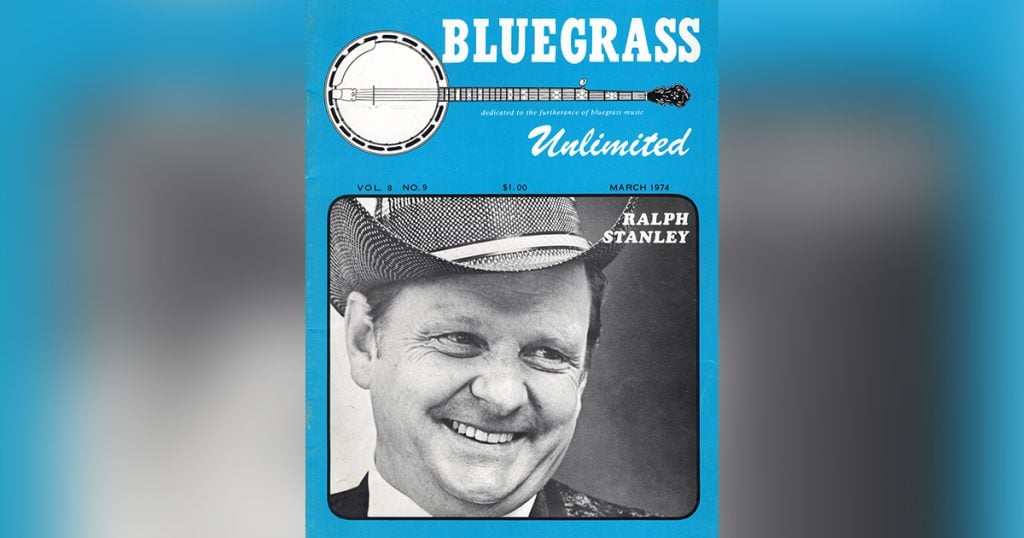

Home > Articles > The Archives > Ralph Stanley: The Tradition From The Mountains

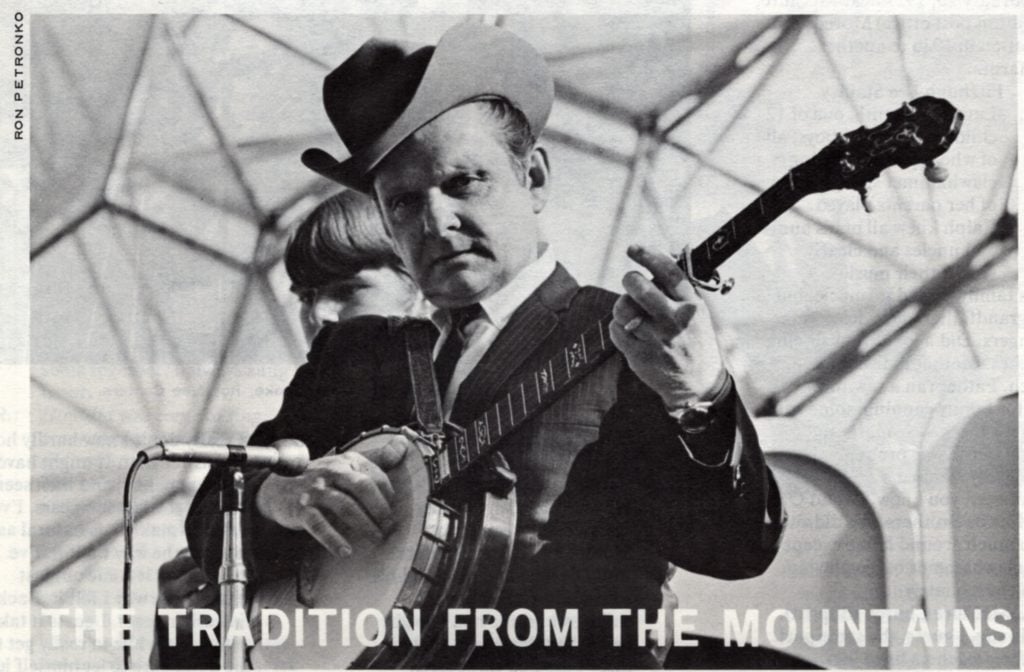

Ralph Stanley: The Tradition From The Mountains

By Ralph Rinzler Smithsonian Institution Division of Performing Arts Washington, D.C.

Ralph Stanley and the Clinch Mountain Boys will be presented in a musical workshop and a full solo concert March 10th at the Smithsonian Institution’s Museum of Natural History, Baird Auditorium, Washington, D.C. While bluegrass has been heard for seven years at the Smithsonian’s annual Folklife Festival, serious attention to this important form of American musical creativity has been overdue in the concert halls of our nation.

It seems particularly fitting that for the Smithsonian’s concert series presenting string band music. Bill Monroe and Ralph Stanley should make their musical statements using the workshop followed by a solo concert. Both men have been highly innovative seminal figures using folk tradition as their base in determining repertoire, vocal and instrumental style and make-up of their performing groups. While they have borrowed, as do all creative artists, from many areas of music, their ability to synthesize successfully seemingly disparate musical elements into a wholly integrated artistic statement characterizes the constantly imitated creative patterns of both artists.

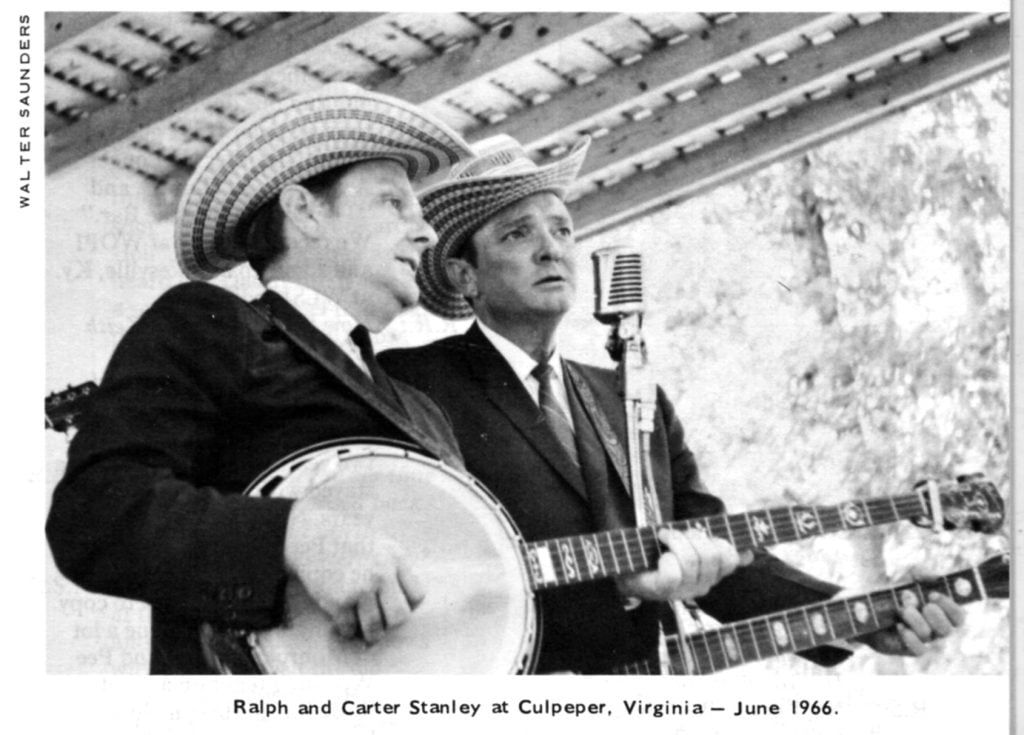

An artist is the best source of information about his own creativity, and his truest statement on that subject is his art itself. There is something about a work of art that eludes description or further clarification beyond what the work itself states. Rather than write about Ralph Stanley’s music and attempt to analyse what I have heard and been deeply moved by over the nineteen years since I first saw him perform at Rising Sun, Maryland with his brother, Carter, this article will honor that simple fact about the elusiveness of art and will consist of an edited version of a conversation with Ralph held on February 10th, 1974. It is an attempt to bring together, in Ralph’s words, the formative influences and background of this modest, extraordinary man who was so impressed by what he heard around him that he forged a music as passionate and distinctive as any being performed today in the field of country, bluegrass, old-time and tradition-rooted music. In the interest of brevity, the format used is a combination of outline and severely edited questions allowing for the inclusion of complete answers.

Interview, February 10, 1974

Born: February 25,1927 near McClure, Va. (Stratton post office) Moved from that location in 1936 to another nearby farm.

Father: Fitzhugh Lee Stanley

Mother: Lucy Jane Smith, one of 12 children, 5 girls, 7 boys, all of whom played 5-string clawhammer style; neither of her parents played.

Ralph knew all of his aunts and uncles and clearly recalls their music.

Father’s family played no music, but father, grandfather and uncles were good singers. Did a lot of lead singing in churches. Mother did sing some, not much. Father ran a sawmill, farmed for family canning, some truck farming for market.

“The first music was probably the Carter Family, Mainer’s Mountaineers, you know. Grand Ole Opry, Monroe Brothers. We didn’t hear too much around home except this old clawhammer banjo playing. Went to church fairly regular…McClure Church (Baptist). They all sang, I guess, the same part. One of the preachers lined ’em. Everybody sung lead.”

R.R.: The harmony singing you later learned to do didn ‘t come from early exposure to church music?

R.S.: No, no the harmony singing didn’t.

R.R.: Were there singing schools around there?

R.S.: No, not that I know of back in them days.

R.R.: How about fiddle playing? Was there any around there?

R.S.: Not to amount to anything. Not too many musicians right around this part of the country where I was raised.

R.R.: Get together and have a dance?

R.S.: I don’t remember about that, but my Mother told me a lot about that during her growing up they had dances. They would play the banjo in that style, you know, and maybe there’d be a fiddler there. She said they would play all night—until the sun was coming up the next morning.

R.R.: But as a boy you never remembered that kind of thing happening.

R.S.: No, I never did know much of that.

R.R.: How many children in your family?

R.S.: Carter was the only full brother I had; my Daddy was married before and my Mother was married before. And her husband died and his wife died. And he had six children and she had one girl by her first husband. He had three boys and three girls. That was three half-brothers and three half-sister, and a half sister by my Mother. None of them played music. I’d say I was eleven or twelve when I started to pick the banjo.

R.R.: Do you remember musical shows coming through where you lived?

R.S.: Yes, there were a few to the high school there. I remember the Delmore Brothers, Dave Macon, and Bill Monroe appeared, Clayton McMichen, Molly O’Day. Back in them days she was called Dixie Lee. She played out of Bluefield and it was sort of headed by a fellow named Gordon Jennings. I believe all that was with her was her brother, played the fiddle, name was Skeets Williamson and Gordon played the guitar with her. I always liked to hear Molly sing. I think she sings it just the way she was raised.

R.R.: It seems that as your music develops over the years, your singing style get closer to an old style. Does it just happen or is it something you think about?

R.S. I really don’t know hardly how to answer that. It might have just happened, and then seems like, in the last few years, I’ve tried to make it as natural as I could…the way I felt it. I’ve tried to let it come out just exactly the way I felt it. Back in earlier years, I guess it takes a fellow a while to really get till he don’t care to let himself just come out the way he feels. It might have been at times that I held back a little bit, maybe just didn’t put it out exactly the way I felt it, and in the last few years I’ve done that. I’d say that’s about the way it is.

R.R. When you started out, did you want to sound like musicians you liked?

R.S. No, Ralph, I didn’t. Most everybody, I guess, that plays this style of music has got pointers from Bill Monroe, but I never wanted to sound like Bill. I wanted to sound exactly like Ralph Stanley.

But I’ve got ideas from Bill. I think the Stanley sound is different from Bill’s, although it is called bluegrass, I think it’s set aside from maybe what they might call bluegrass.

R.R. When was the first time you and Carter really started to sing together? Did Carter play a banjo?

R.S.: Carter could play a tune or two on the banjo. I think he used his forefinger and thumb. We used to play at home a lot, on Sunday, you know, and of a night before we’d go to bed. And our Daddy, he usually had business to take care of. He worked men, in his job, and he was a little nervous and he’d usually run us out of the house. We’d go anywhere we could get to play and sing a little. Carter got a guitar before I did the banjo and immediately after we got ’em I’d say we was trying to sing some together. I always sung tenor.

R.R.: How did you come to sing tenor the way you did…how did you start?

R.S.: The only way I can tell you is, I just started singing and the way it come out is the way that I done it. Like I said a while ago, for several years, I couldn’t let it out like I wanted to, and I would hold back a little, you know. And the last few years, though. I’ve just let it come out exactly as I felt, and I never tried to copy anyone on singing tenor. Just like I’m talking right now, the way it comes out is the way its coming.

R.R.: It’s an unusual way of singing tenor.

R.S.: I’m one of the very few…well now, I’d say Bill Monroe does too…I just about lead the lead singer with my tenor. I’ve seen Bill Monroe do it some. There’s not many tenor singers that does that. I can sing tenor on any song that I know without the lead, with every turn and everything in it that I do. I don’t listen to the lead; I just sing it and then they’re usually in with me.

R.R.: When you were starting out, where did you get your songs from?

R.S.: Well, just songs that we’d heard other people do, you know, and then my Daddy, he sung a lot around home. He knew a lot of songs. He sung “Man of Constant Sorrow”, “Pretty Polly”, “Wild Bill Jones”…that’s all I can think of right now.

Now, I don’t remember just where I got “Little Birdie”. Carter wrote more songs than I did. I’ve written, I’d say, forty or fifty songs. Carter and I first started in Norton, Virginia in October or November, 1946 on WNVA radio sponsored, I believe, by Piggly Wiggly, a 15 minute show at 7:00 a.m. We played about thirty days in Norton, and then we went to Bristol and started Farm and Fun Time in December of’46. We were both in the Army in World War II, and Carter was discharged in March and I was discharged in October of ’46. Carter’d been playing there a few months with another group. When I was discharged, I played a couple of weeks with them. We started our own group then.

Pee Wee Lambert was in the group with Carter. He left with us. We heard about this new station going on the air and our Daddy went up there and talked to them one day. As it was, they were planning to start this hour program, and they didn’t have any talent to start it with. They said, “We won’t promise you a thing. If you want to come and play the hour by yourselves with no pay or anything”, so that’s what we did. That was WCYB at 12:05, right after the news for 55 minutes. We had handbills made up with the call letters of the station, and the name of program and the time it was on. We were on there twelve years off and on.

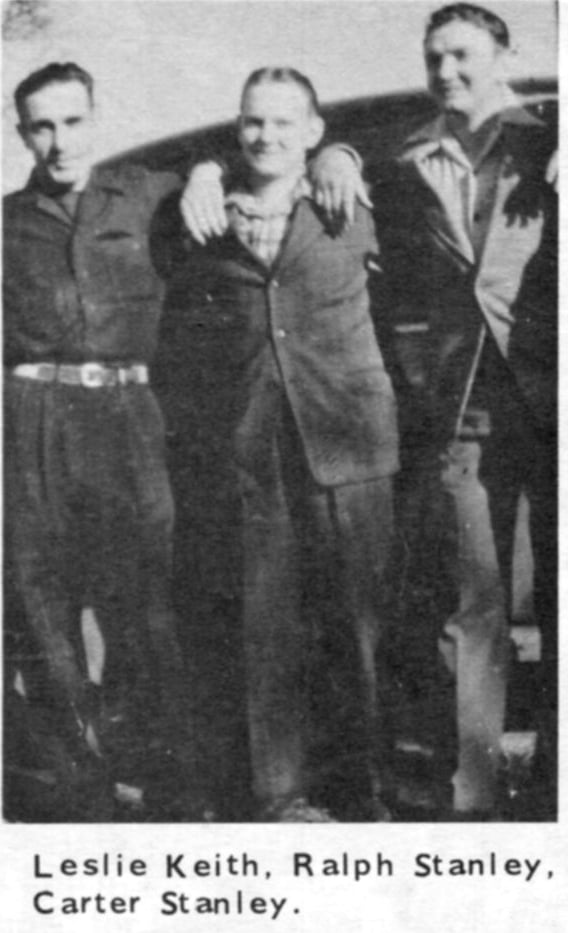

The first appearance that we played there were four of us. And we split, and we made, I believe, $2.55 a piece. And the next night we played a fairly good sized school. I don’t remember what we took in, what we made, but anyhow we had two shows — two full houses. And from then on we just couldn’t hardly find buildings around big enough to hold the people. That was about a week after we started at Bristol. The band was me and Carter, Pee Wee Lambert and we had a boy playing the fiddle by the name of Bobby Sumners. He didn’t stay over a couple of weeks. He left and we got Leslie Keith.

We left Bristol a couple of times, but we never did stay maybe over two months. We went to Raleigh, N.C. once, and we went to the Louisiana Hayride in Shreveport, La., and we went to Versailles, Ky. But we didn’t stay long. We’d always come back to Bristol. We were the first group that played on Huntington, W. Va. television, I believe, in 1949.

R.R.: Did you ever think about getting electric instruments and changing your sound?

Did you ever consider it?

R.S. No, I never liked electric music; never will. Never would ever discuss a Dobro. I like a Dobro alright, but I never did like a Dobro in this type of music.

R.R.: How about double fiddles?

R.S.: Yes, we use twin fiddles.

R.R.: Do you ever play fiddle, guitar?

R.S.: No, I don’t play anything but the banjo.

R.R.: How did you start to record for Rich-R-Tone?

R.S.: Well, this fellow by the name of Hobart Stanton had this company in Johnson City. We didn’t know him. I guess he heard us on the radio station and he contacted us, and we made some records for him. We recorded in WOPI radio station in Bristol. At that time we didn’t know A from B. We didn’t know about things like that. And he didn’t pay us anything; just promised us some royalty on the record.

We were glad just to get some records out. I was told by a fellow the other night that Hobart told him that the record of “Little Glass of Wine” sold 100,000 copies. I know we were sponsored by a store over in Honaker, Virginia called Honaker Harness and Saddlery and the “Glass of Wine” version was released. They got us to come over and play at their store on Saturday and they bought 1,000 of this record. And I know they sold that thousand out that one day. The first time we recorded, I guess, two songs: “Mother No Longer Awaits Me At Home”, and “The Girl Behind the Bar.” We recorded some at WOPI and some up at Pikesville, Ky. at WLSI radio.

R.R.: How long did [Leslie] Keith and [Darrell “Pee Wee”] Lambert stay with you and Carter?

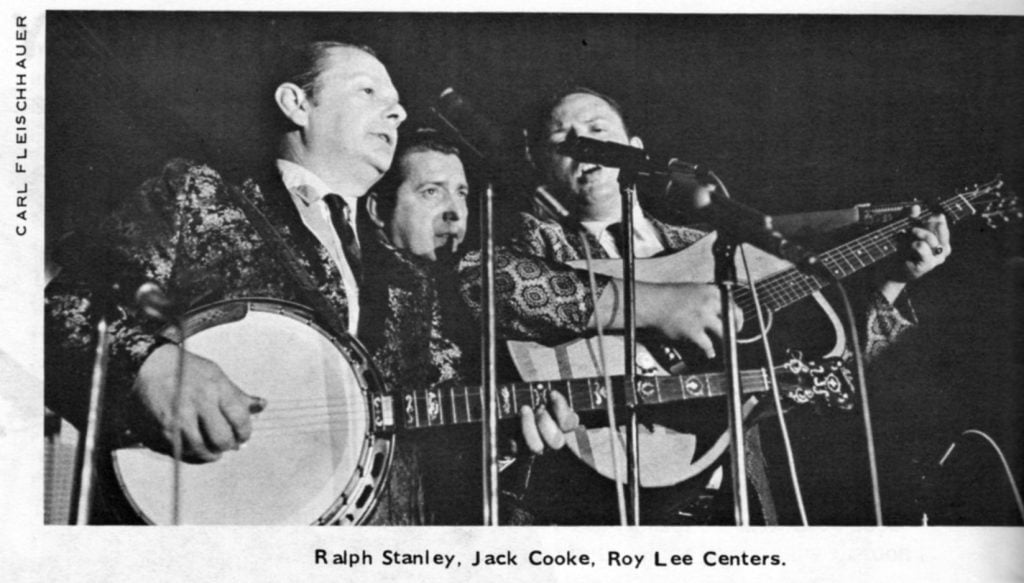

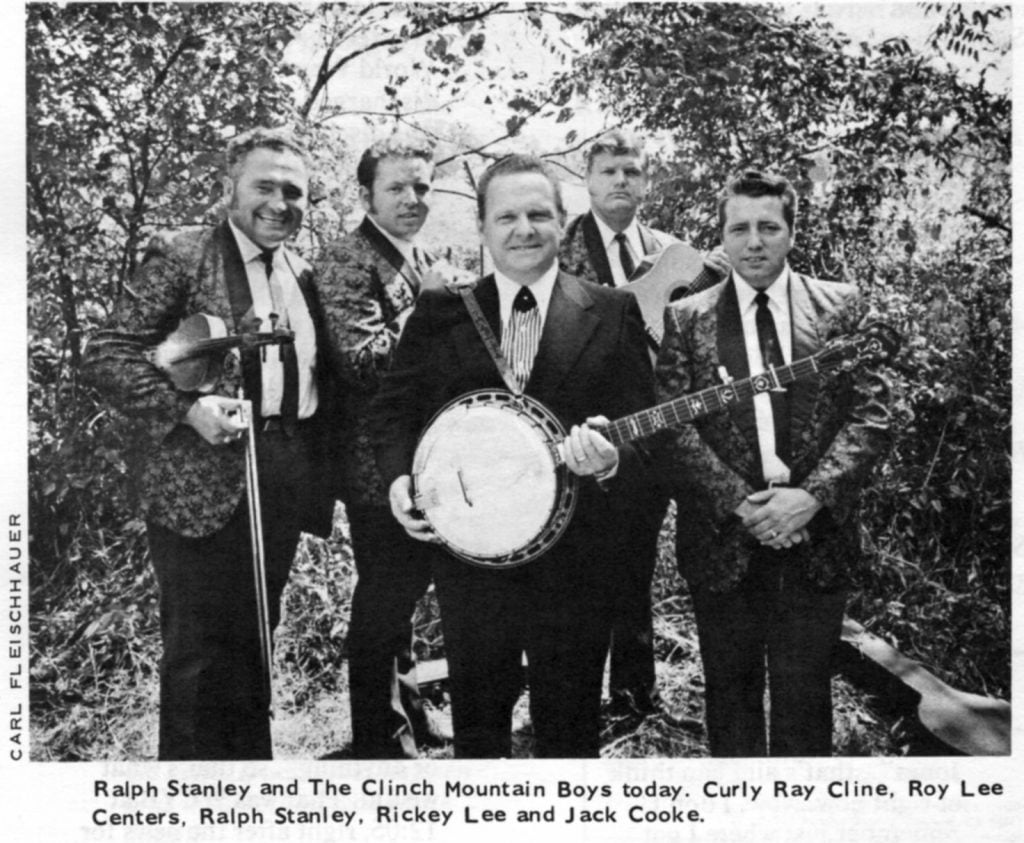

R.S.: Leslie stayed with us about two years and I guess Pee Wee stayed with us about four years. Now, during the time that Pee Wee stayed with us, he copied Bill Monroe on the mandolin and he tried to copy his singing and we done a lot of Monroe numbers and Pee Wee sung tenor on a lot of those songs. He sung high baritone on some of the trios. After Pee Wee left, we got down to doing the Stanley style. After that Curley Sechler worked a little while with us on the mandolin, and Bob Osborne worked a little while with us on the mandolin. Then Bill Lowe and Jim Williams. Then, for a long while, George Shuffler was with us on lead guitar. I don’t have a mandolin now. We’re using two guitars now and banjo, fiddle and bass. (Roy Lee Centers, rhythm guitar and lead voice; Curley Ray Cline, fiddle; Rickey Lee, lead guitar; Jack Cooke, bass.)

R.R.: When did you start to play finger-style banjo?

R.S.: Well, I was playing with one finger and thumb when we started working professionally. Very soon after I started playing banjo, I started with finger and thumb…a little of the other too. After Rich-R-Tone we recorded for Columbia. Art Satherly called us one day on the telephone and said he wanted to sign us on Columbia records. We signed, I believe, with Columbia in 1947, but I don’t remember exactly what it was, some kind of ban on the union, you couldn’t record at that time, and we had to wait until that was settled.

I believe it was 1948 when we first recorded for Columbia. We were playing in Raleigh, N.C., WPTF, at that time and Art Satherley flew down to Raleigh and signed us to a contract. Then we went to Mercury after five years with Columbia and stayed with them five or six years, signed by Dee Kilpatrick, he was manager of the Opry for a while. We signed with King in 1958, Sid Nathan. I guess we stayed with them 10 or 11 years. Then between contracts we recorded some for Starday, Jaylyn, and we signed with Rebel about two years ago, Charles Freeland.

When Carter died, I didn’t know how well I’d do, but I knew I had to do something. It seemed like right soon after he died I got letters from people. I got phone calls. Everybody telling me how they was behind me, how they were expecting me to continue. Of course, that helped me up. I just made up my mind that was all I could so and I was gonna do it. About six or seven months after Carter died, I went to Sid Nathan and talked to him and told him that I would like to record, and I asked him if he wanted me to stay on with him. And he said, “Why not. The Stanley Brothers have really done well for us and who knows, you might do better.”

R.R. Where do you learn the old songs from? Where do you find them?

R.S. People, you know, might know some old songs and maybe send me one. I always like to learn any of the old stuff that hasn’t been put out by other people. I like to do that. I like the old songs. I’ll write one now and then. Now, “Going Round This World, Baby Mine,” I believe I first heard that in Renfro Valley, Kentucky played by Lilly May (Ledford) and the Coon Creek Girls. “Jacob’s Vision” I learned from Enoch Rose; he was a Free Will Baptist preacher from Caney Ridge, Va. “Village Church Yard” we learned at the McClure Church. Our Dad and his Brother, Jim Henry Stanley, used to lead that one. He worked for Dad; used to drive a team of horses for him in the woods logging. And he would come home with Dad now and then and they would set up late at night and sing a lot of the old songs like that. Now “Little Glass of Wine”, we heard a fellow do a little bit of that. He had the melody to it, and we wrote a lot of the words to it. This fellow worked for W.M. Ritter Lumber Company; his name was Otto Taylor. That was back in ’37-38. He played the banjo-used one finger and thumb. Didn’t learn any other songs from him. “Drunkard’s Hell”, now that’s a song we heard our Daddy do. If I hear a song I like and feel that I can put it in our style, you know,

I do it. I can sort of feel how I can do it the best, claw-hammer or finger style; I can just sort of feel it.

R.R.: You knew some of the old time musicians who recorded back in the twenties and thirties, Ralph. Which ones were they?

R.S.: Tom Ashley, he contacted us at the radio station in Bristol and Tom played a lot of shows with us. He played the old black-face comedian, Rastus Jones. And Fiddlin’ Powers. I knew him very well; he was with us a lot of appearances. He’d come and stay a week or ten days at a time with us. He was from Castlewood, Virginia. His real name was Cowan Powers. We sang at his funeral back in ’54 or ’55. He was 75 when he died. The last seven or eight years before he died, he’d come up about once every month or so and stay a week with us. He come to know us by hearing us on the radio and that’s how he come to play with us on shows and on the radio too.

R.R.: What did your parents think of your music?

R.S.: Mother would play banjo when I’d ask her round home, you know. She died last May; she was 86. Daddy died in 1961; he was 73. They were real proud of our music.

They always felt that religion had its place and music had its place and neither didn’t interfere with the other. They believed that it depended on the individual. My music? I don’t know what you’d call it…I just think it’s old time mountain music.