Home > Articles > The Archives > The Lonesome Sound of Carter Stanley

The Lonesome Sound of Carter Stanley

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

June 1976, Volume 10, Number 12

One chilly afternoon last November I drove the sixty-or-so miles from my home in central Ohio to The Country Palace, a tavern on the southeast edge of Columbus, to talk with Ralph Stanley, who was booked there for the weekend. I had been asked some four or five months earlier to write an article on Carter Stanley, or to be exact, on Carter’s music, but I had been held up by the nagging feeling that Carter’s music, which already spoke quite eloquently for itself, did not need an article written about it. But agreements are agreements, and I was hoping that Ralph would be able to dissolve the perplexity I was in over the question of the “lonesome sound” — I wanted to know, in a practical as well as a theoretical way, what the lonesome sound was, and something, perhaps, of what it had come from, so that if I could not hope to say in words what Carter had said in music, I might at least speak for the music and its many strange and unique powers.

I was eager to write. My Thanksgiving holiday (I am a teacher) had just begun, and the prospect of a few days’ liberation from the classroom, during which I might find some time to write, was beginning to exhilarate me. I had spent the morning hour in a gloomy lecture hall, where the handful of students who had not already left the college for the week listened indifferently to my studiously dull lecture on the medieval monastery, where during the barbarian invasions after the collapse of Rome, I think I told them, Christian monks had secreted themselves away with the ancient Greek and Roman texts which by assiduous study and careful reduplication they had saved from extinction, while at the same time tincturing them with their own unmistakably Christian outlook. But my confused reflections on this subject, as I drove towards Columbus under a cube-shaped winter sun, gradually gave way to the more homely ideas which I was anxious to try out on Ralph: that to sing lonesome meant, as Larry Sparks had once told me, to sing with feeling; and that to sing “with feeling” meant to sing in the traditional fashion—that is, with a feeling for the music. The lonesome sound, I felt sure Ralph would confirm, was tied up somehow, precisely because it was traditional, with the past—not only with the past of an individual man, but with the larger and more inclusive past which his music evoked and embodies, a past that reached from the cities of the present, to the mountain farms of recent memory, into the fabulously distant past of English balladry, where Lords and Ladies stood fixed in the sea of pure imagination between the old world and the new, or else had been transformed into the rogues, ramblers and sweethearts of our more democratic experience. In short, I had nearly conducted the entire interview in my imagination before I arrived, and by the time I actually did arrive I felt strangely ridiculous, as if the interview, and all the anticipation I had lavished on it, had suddenly become superfluous. I knew what I wanted to say; why did I need Ralph to say it for me?

It is not easy to get lost in Columbus. I got lost because I had completely mistaken the sort of place I was looking for. In recent years I had seen Ralph Stanley play at summer bluegrass festivals, at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, and even at Avery Fischer Hall at Lincoln Center. Partly under the sway of such associations, and partly under the influence of the very name—The Country Palace—I had come to expect something quite splendid: something which had the grandeur of a villa on the Mediterranean and somehow at the same time the rusticity of a cabin hidden away in some leafy holler in the blue ridge. I was, in fact, so dominated by my curious and fantastic conception of the place that I drove right by it, and had to be directed back along the route I had already taken by a grinning service station attendant who probably thought he knew why I was looking for a bar at three o’clock on a Friday afternoon.

The Country Palace, which was identified only by a very inconspicuous sign, turned out to be a long warehouse-like building which had been, it was obvious, only fairly recently converted into a bar. It was made of cinderblock and painted the vapid green color of a throat lozenge. Spreading out from the base of its vast blind western wall was a gravel parking lot that terminated in a strip of unruly grass and what appeared to have once been a coal depot. Beyond the tavern in the other direction were a few shoddy tract houses, a junked car, a filling station with its windows cracked and pumps torn out, and a few whithered fields grimacing under the cold sky—the debris which midwestern cities leave behind as they withdraw into their desolation. As I emerged from my car I felt an elusive but penetrating anxiety, as if I were trespassing, and I recalled momentarily the peculiar melancholy I used to feel as a boy when, in the reddening winter twilight after school I used to ride my bicycle home through the silent avenues and empty lots of the warehouses and steelmills that made up the better part of my hometown.

As I entered, two men, one of them in a day-glo hunting cap and the other in mechanic’s overalls, who were seated not five feet from the door, and whose conversation I had interrupted by admitting a cold breeze from outside, paused to look at me; and they looked so long and hard, and so completely in unison, that I nearly stopped to see if I had remembered to put my pants on. I responded with a nervous and slightly affected “How’re ye?”-but I was alarmed, and wondered if I had not made some horrible mistake. Was The Country Palace a private club of some kind, a sort of VFW Post or union local? “Naw,” I thought…”couldn’t be.” So I went ahead, into what turned out to be a vast, low, and largely empty room, faintly reminiscent of a parking garage, shrunken by shadows and set about with flimsy card tables that seemed ready to buckle under the weight of the checkered tablecloths that had been thrown over them. On the wall adjacent to the door was the bar itself, with its electric beer-clocks and advertising gadgets throwing off sinuous points of light into a panel of vertical mirrors in which the solitary drinker might regard himself, and in which the four or five men who were sitting at the bar were imperfectly reflected. Ralph Stanley, the barmaid told me, was out, but was expected back at any moment: would I like to have a beer while I waited? She was quite warm and cheerful, and my uneasiness let up a bit; as I sat down at a nearby table with a package of beer-nuts I felt inordinately grateful to her, and smiled at her once or twice, to show my appreciation. In a few moments my presence there was no more significant than the presence of a couple of houseflies, and I began to feel quite secure.

As I sat alone I got to thinking. Who doesn’t get to thinking when he sits alone? I had forgotten, I realized to my embarrassment, that bluegrass music, which I had followed more-or-less passionately for fifteen years or so, had not begun in, nor survived in, nor come to maturity in the Smithsonian Institution or at Lincoln Center. I remembered an old friend of mine named Ernie, a coal-miner, who, having come north seeking work, and having found it in the hotel kitchen where I happened to be a receiving clerk, played the “Fox Chase” for me on the mouth-harp, and asked me if I had ever heard of a man named Bill Monroe. I hadn’t. I remembered the incredible astonishment and joy I had felt one afternoon at Chicago’s Old Town School of Folk Music, which in those days was nothing but a dilapidated loft, littered with cigarette butts, where I heard a local banjo player named Ramsay, who must have been about seventeen then, and whose blonde hair was piled on his head like the wool of a just-shorn sheep, rip off Scrugg’s “Lonesome Road Blues.” Ramsay had broken his leg, and in order to play had to tuck his crutch under his picking arm and lean on it, holding his heavy cast ankle-high and balancing himself against the weight of the banjo, an old ball-bearing Mastertone, which looked to me like something halfway between a Chippendale chair and a gatling gun. I had never heard anything like it: it sounded like three million dollars in dimes. I recalled also the record store I had stumbled upon, a place no bigger than a broom closet, one day in Uptown, then a neighborhood of Appalachian immigrants, now a district of boutiques, head-shops, and other hip establishments, where I found bins laden with the likes of The Stanley Brothers, Bill Monroe, Reno and Smiley, Flatt and Scruggs-names I had just then begun to recognize-and my excitement at the discovery, as if I’d won a lifetime’s supply of groceries. I was too young, then, to go into the bars; but I used to venture there at night, sometimes quite afraid for myself, and peer as long as I dared into the window of some recondite place where a bluegrass band might be playing. I never had much luck-but I had forgotten, now many years later, that in those sullen and sometimes unsavory places bluegrass music had been preserved and sustained by great musicians like The Stanley Brothers in the face of immense social and economic pressures against them, and that the more recent successes of bluegrass music had probably very little power to erase in the mind of a man like Ralph Stanley the much longer and more pungent memory of tedious highways and one-night stands, a memory which he must have felt an impulse to revive from time to time, and thereby hold together the slender but complicated network of people who made up the community of bluegrass music. My lecture of that morning was still on my mind, I suppose, because the thought struck me-strange and inappropriate as the comparison might seem-that the Country Palaces of the South and Midwest have been a kind of haven, like the monasteries of the middle ages, in which the venerable literature of mountain music, expelled for the last time from the isolation which had nurtured it, had been preserved against the barbarian invasions of poverty, migration and, perhaps the worst of all because it exploited a peoples’ loss by seeming to restore that loss, commercial country music.

I wondered if bluegrass, having blended, at considerable expense to itself, into the mainstream of our national life, weren’t more in danger of extinction now than it had been while secure in the arms of its natural audience. I deeply regretted some of the ways in which bluegrass had been misunderstood and exploited in recent years, and the way in which the term itself had expanded to include almost any kind of music, however hybridized, that had a banjo or a fiddle in it. And yet I suspected that I had unwittingly involved myself in this very process. What reason could Ralph Stanley have for distinguishing me from any one of the mass of hip journalists who flock to bluegrass festivals in search of trendy material for an audience whose attention won’t fix itself on anything that is not fleeting? I was afraid that as far as Ralph was concerned, I was simply another of the upstart bluegrass aficionados who had never known the music in any other context but folk-rock, the feature film, the television commercial, and the like-who had never known it, in other words, except as a fashion, something vaguely associated with blue denim leisure suits, crunchy granola and earth shoes.

I waited for Ralph a longtime. Behind me, at the bar, as the hour grew late, new patrons had arrived, and new conversations sprung up. Two men, one a burly day laborer and the other a dapper gentleman in a rancher’s outfit, were arguing about Jimmy Skinner’s latest surgery: had it been gall bladder, or kidney stone? Two steps down the bar a very large and powerful-looking man, who would have done very well on the Ohio State defense line had he not already been employed by the Highway Department, and who had obviously been working like the devil all day, was complaining stridently that no one ever listened to him. A friend, much smaller than himself, tried in vain to reassure him, until the rancher turned around to tell the large man that everyone at the bar appreciated what he had to say, which somewhat surprised the large man, since he had not, strictly speaking, said anything. Just about that time the jukebox, which had been sitting like a washing machine in a darkened corner of the room, lit up like a Buick, and began to pour into the room a gaseous mixture of Nashville and Studio-bluegrass, adding to the many distractions which had muddied, my growing anxiety that Ralph had forgotten about our interview. I had called him that afternoon; he had been so polite on the telephone, and persuading him to an interview had been so little work for me, that I began to suspect he had misunderstood me. It had been, after all, noisy at his end: the sounds of restless and incessant talk, laughter, loud music- altogether the balmy chaos of a tavern at week’s end in a cold month.

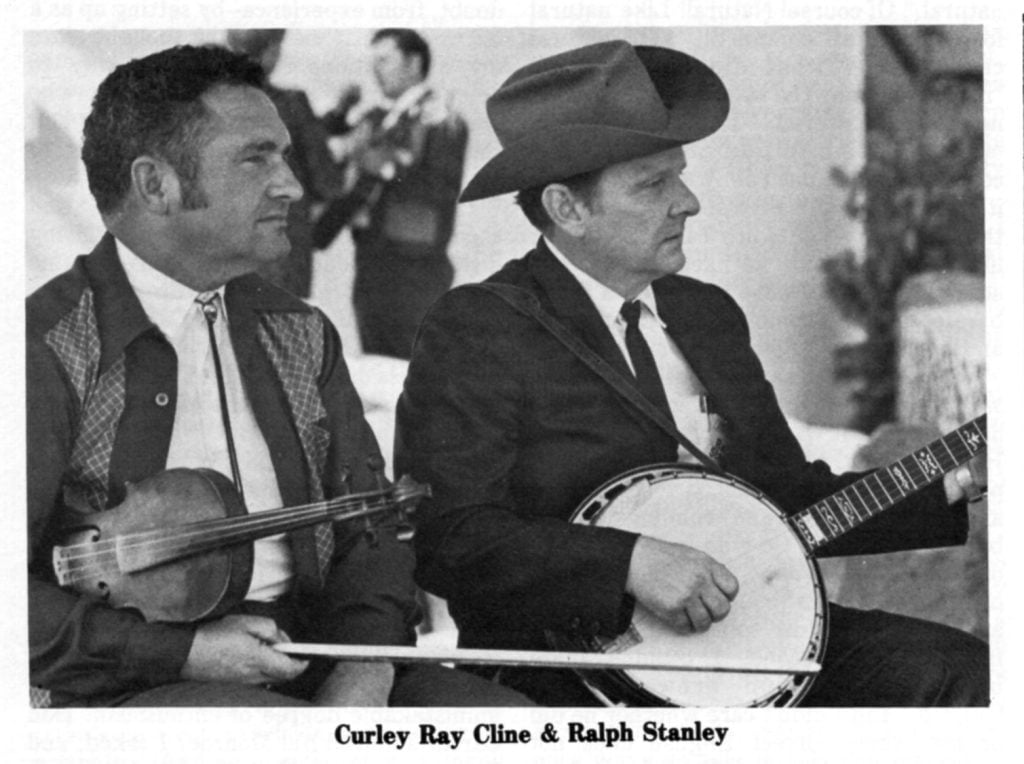

But Ralph finally did arrive, and no longer had I begun to introduce myself than he was apologizing for the delay; none necessary, I assured him, and we were soon sitting at a table near the middle of the room, while Curly Ray Cline, who seemed to have materialized out of nowhere, was sitting at the next table before a hearty supper.

Looking back on the interview I don’t know how Ralph kept himself from chuckling. I was absurdly awkward with the cassette recorder I had brought along, and I introduced my plan for the interview, and for the article I hoped would come from it, with a blast of hot air that must have pretty nearly choked him. The worst of it was that I tended to be too hasty, and to supply Ralph with thoughts and words that actually were my own, or to cut him short before he had developed his idea. It was apparent that I had never conducted an interview before, and I was stage-struck; but Ralph was cool and businesslike, and he seemed to know, in a sort of unnerving way, precisely who I was, and what I wanted, and what I expected him to say.

Or, at least, he thought he knew. Almost immediately my worst fears seemed to be confirmed. I realized almost the moment we began to talk that an interview reflects as much or more the interviewer’s prejudices as it does his subject’s opinions, and that the skillful journalist, which I was not, will somehow eclipse himself, so that his man is talking, not at him, but through him. “Carter enjoyed his music, and respected it, and he wanted it done right, the best that it could be done…’’-so far so good-“…done natural.” Of course! Natural! Like natural foods, natural childbirth, and natural causes. And what did he mean by “natural?” “Why the way I’m talking right now,” he answered. “The way it comes out. Not trying to talk proper. I know correct English, but I don’t use it, because it’s not the way I was raised.” What about that, the way you were raised… “Carter liked to coon hunt, he liked to fish, and squirrel hunt-we were raised on a farm, barefooted boys running over mountains and hills, stubbing our toes on rocks…” Well, I ought to have loved it. Bluegrass was turning out to be just what I would have thought it was, had I been, let’s say, Helen Gurley Brown: a natural music, played by natural country folks fishing and coon hunting and running around barefoot, just like they do in Dogpatch. I ought to have loved it, but I didn’t. First of all, I had always thought of bluegrass as an art, and art as something different from nature. Second, I couldn’t quite believe that Ralph knew “correct English,” and I didn’t care whether he did or not, since correct English does not necessarily make good English. Ralph’s English suited me just fine. And finally, I didn’t need to be reminded that Ralph and his brother were the genuine article-I knew they were genuine, and that the sentimentality in Ralph’s Rockwell-like portrait of himself as a boy was something more urban than rural. It seemed that Ralph had begun-having learned, no doubt, from experience-by setting up as a barrier against me what he thought were my expectations. What better way to defend yourself against a marauder, who wants to meddle in your private life and thoughts, than by returning the image of himself?

I was profoundly disappointed, and thought I did everything to conceal my disappointment, my questions became hasty and disorganized, and drew answers equally perfunctory; yes, Carter was a fine person, yes, he had a sense of humor, no, success didn’t affect him, yes, he loved his home place—I began to feel that I had quite simply failed. But when I asked, offhandedly, about Bill Monroe’s effect on Carter, Ralph’s attitude seemed to change. It was a change so slight as to be scarcely noticable; but I noticed it. What had been a coldly formal interrogation began to take on the more relaxed quality of a conversation, and I believe that Ralph, who is not a terribly demonstrative man, began to answer with a subtle but unmistakable degree of enthusiasm. Had Carter admired Bill Monroe? I asked, and if so, what was it that he admired-was it Bill’s high singing?

“Bill Monroe was Carter’s idol,” Ralph said. “He thought Bill Monroe was the greatest.” No, it hadn’t been the high singing, but the quality of the singing: “Bill’s got a pearl in his voice; he’s got a bell in his voice.”

And about Carter’s songs: “Most of the songs Carter wrote,” Ralph said, “were true to life, everyday life. They were not necessarily the things he experienced, but something which he realized him or anyone else could experience. He liked songs with a story.”

Was this true, I asked, of a song like “Lonesome River” or “White Dove?” “A song like the White Dove,” Ralph answered, “is the backbone of the Stanley Brothers. If you were ever to go to the place where we was raised, and look around, and study the words to the White Dove, you could just see it in your mind. Carter really loved our parents, our mother and daddy, and he dreaded the day when, according to nature, we’d have to give them up. In the White Dove he visioned that—he had always visioned going back home, and they wouldn’t be there.”

Carter Stanley, it was obvious, was something more than a simple country boy, singing, as frogs and crows sing, “the way it comes out,” but an artist, with an artist’s love of precision and power of sympathy. And as an artist he was linked to his tradition, and his songs to his own experience. I wanted to know where the image of the White Dove had come from; I knew that a dove was occasionally engraved on the title-pages of church hymnals, and on gravestones, and was even sometimes fashioned into the tiny silver knobs by which the lids of caskets are secured. Furthermore, as everybody knows, the white dove is a symbol of peace, as well as of the Holy Ghost, through the Gospel of John. It had even been, hundreds of years ago, an emblem of the preacher, whose words betoken the spirit of the Holy Ghost in him, and purity of his divine message.

But Ralph couldn’t satisfy me. “No, I couldn’t answer that. Carter wrote that song one night…we had been to a personal appearance somewhere…it was one of his first songs. He was in the back seat of the car when he started writing that, and by the time we got to the radio station near home we had a verse and a chorus worked out. I don’t know what caused him to think of the white dove, except that he was studying on it, and how it could affect you…”

That the origin of the white dove was mysterious was, I thought, entirely appropriate. Carter had made it a mystery: “White Dove, we’ll mourn in sorrow…” It is as if the song were addressed to the white dove, and to a ministering angel, whose brilliant presence plays no role in the song except to cast its white and purifying light over those feelings of doubt and loss which, while they seem to divide the soul from the sources of its happiness, are an unmistakable sign of the singer’s absolute faith. Out of the tender and entirely honest solicitation of his own feelings Carter had produced a song which, because it is so utterly simple and honest, it is possible to love; one cannot help but compare it to the more topical and superficial music of recent folk and bluegrass singers who make it impossible for us to love them because they are always interposing themselves between us and their music. Their songs are merely autobiographical; Carter’s songs are true.

This must have been, I thought, what Ralph meant by “natural.” The music of the Stanley Brothers is entirely free of those artificial elements such as hyper- technical instrumental breaks and arbitrary experiments in style, which, because they call attention to themselves at the expense of the music as a whole, sometimes betray the artist’s interest, not in art, but in himself, or at the very least, in success. The music of the Stanley Brothers-the parable-like simplicity of Carter’s narratives, the dusky plaintiveness of Ralph’s voice and his sturdy banjo—neither dazzles us with its complexity nor allows us to gaze wistfully into a reflection of ourselves. We must listen with imagination, and in the process take on their thoughts and feelings as our own. That is why we do not tire of the Stanley Brothers.

But as Ralph spoke, something new seemed to be emerging, not only from what he was saying, but from the entire situation around us. It had begun, I supposed, with the sharp red sky outside, and the cold; and it extended to the handful of men at the bar, and their discussions which, as I saw it, struggled to place them in the wider universe outside the confines of their own lives, which it is the function of the imagination to do. And ultimately it extended to Ralph’s image of his dead brother, hidden in the back seat of a dark automobile in the very late hours of the night, far from home, writing a song in which he “visioned” what he most feared, the deaths of his mother and father, and with them, the death of his faith. It seemed that bluegrass music had not only been preserved on the road and in the tavern, but had changed there too, just as classical literature, native to the sunny Mediterranean, had changed in the pious and dismal monastery, where the living world, both its joy and its suffering, was closed out. Hadn’t bluegrass music learned to express, in a way more acute, more demanding, even, sometimes, in a way that was abrasive and tiresome, the loneliness of men far from home, perpetually among strangers, who have personally suffered the separation from home and loved ones that their art has made imperative? And didn’t a musician like Carter represent, in that separation, most of his own audience, who for different reasons had experienced the same feelings? Carter’s songs show that he had the tavern, and the highway, and the bottle much on his mind. He suffered, not only from the loneliness and doubt of which he speaks in his songs, but from an addiction to what folks in taverns consume to combat those feelings.

“In the last few years of his life,” Ralph said, “Carter was unhappy, because he knew he was sick, but he was a fella who wouldn’t give up. He thought he could conquer anything, and he wouldn’t admit…he knew it was coming, and still he wouldn’t admit it. In his later years, his last years, he really loved his children, and he missed them when he was away from them. He often talked about them. He would have liked to be with them, but he knew he couldn’t. Ralph went on to say that Carter’s daughter had finished a song which Carter had begun to write about Ralph, which she called “Lonesome Banjo Man.” “It’s got in it exactly what has happened,” Ralph said. “It’s about Carter’s passing, and me going home—some strong words. She says in it that you can see a smile on my face, but you can tell deep down I’m reliving a lot of things that are in the past.”

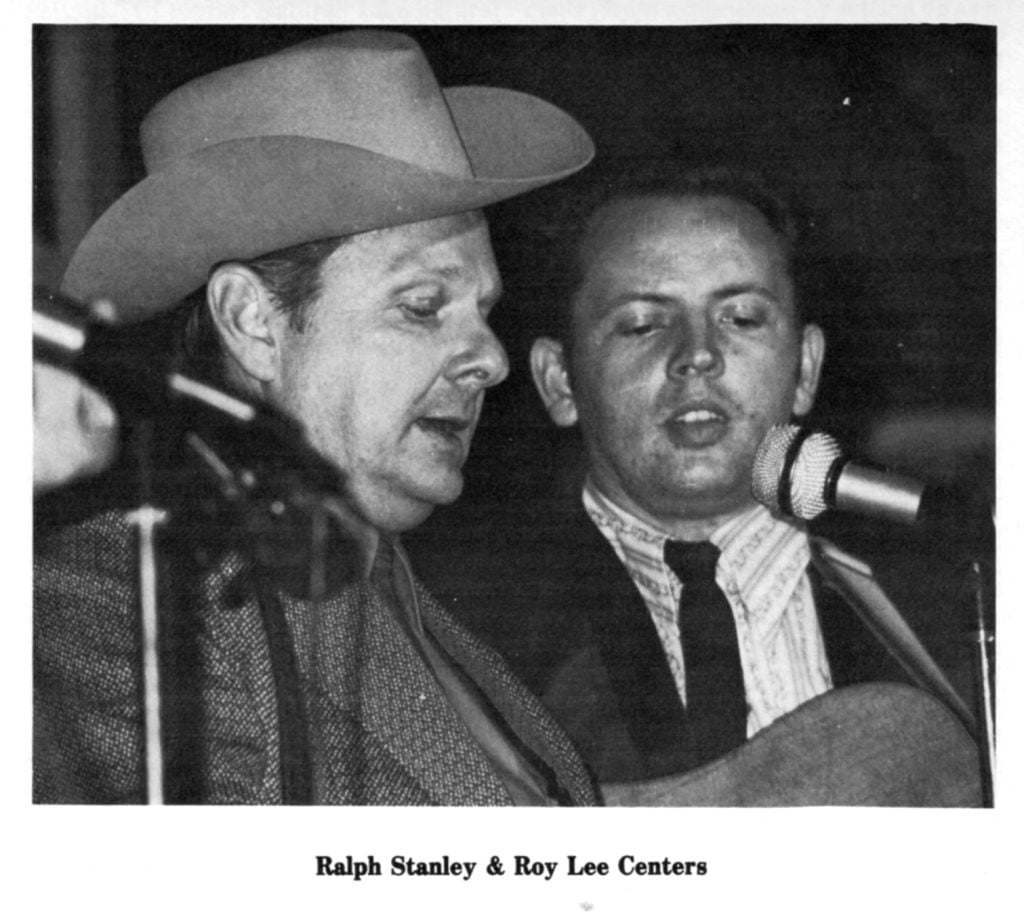

Looking back on that last remark, I wonder if I did not somehow plant the idea of reliving the past in Ralph’s mind. I don’t think I did. Anyway, it doesn’t matter. I haven’t reported, of course, everything that Ralph said, though he said many interesting and surprising things—for example, that at times he had been unable to distinguish the late Roy Lee Center’s voice from Carter’s, or that he’d often thought he’d like to give up the banjo and only sing, or that there hadn’t been much music around them when they were growing up. He interpreted the lonesome sound as something God-given, something “given to us by Someone who has more power than any of us has.” Our conversation seemed to end of its own accord, and though I felt there was a great deal more to say, I could not think for the life of me what it might be.

The Country Palace has taken on a sombre quiet. Most of the patrons had gone home to dinner, and the bar was empty. The light over the billiard table was out, and the jukebox silent. As I rose to leave, I thought I detected, and perhaps I am imagining it, a slight, very slight, dismay in Ralph’s expression. I think that, in a very small way, he was sorry to see me go. He asked me a few questions about myself, and I asked, in return, when would he be in Columbus again.

“New Year’s Eve,” he answered. Though he had a busy schedule that included festival dates, college concerts and the like, he had always made it a point, he said, to keep up his old contacts at places like the Country Palace. As I drove back home in the dark I tried to picture the scene on that evening, when the place would be a blaze of talk and laughter, scribbled over with streamers and crepe paper, while men and women in paper caps and dusted with confetti joined in with voices and paper horns while Ralph Stanley and the Clinch Mountain Boys, five hundred miles from home on New Year’s Eve, sang that old traditional number, “Auld Lang Syne”—bluegrass style, of course.