Home > Articles > Special Series > Bluegrass 45 and their Historic 1971 US Tour

Bluegrass 45 and their Historic 1971 US Tour

It has been fifty years since the Japanese bluegrass band Bluegrass 45 toured the United States—from June to September in 1971. In order to help document this tour and give Bluegrass Unlimited readers a better understanding of the popularity of bluegrass in Japan and how a Japanese band was received in the United States in the early 1970s, we are launching a sixteen-week online article series based on Akira Otsuka’s photographs, journal entries, and recordings. This will help portray the events from the perspective of the Japanese band. Additionally, we will print quotes based on interviews with American bluegrass artists and fans who saw the band perform and met the band members during their tour.

The article we release each week, from June to September 2021, will correspond to the band’s activities during the exact same week from fifty years ago in 1971. The first installment from Akira’s journals will be printed next week. Although the part of the story that Akira will introduce next week occurred in 1970, we will title this entry “week zero” since it is the precursor to “week one” of the Bluegrass 45 tour. The week zero article will correspond to the events that occurred in Japan leading to the band’s being booked for the US tour. In that regard, I suppose that this article you are now reading can be called, “week zero, minus one.” The intention of this article is to introduce you to the band by outlining how they got interested in bluegrass music in the first place and how they came together to form a band.

Bluegrass in Japan

Most bluegrass musicians and fans are aware of the popularity of bluegrass music in Japan. Many US bands have toured in Japan or played at a theme park there. Some have also famously recorded live albums in Japan. In order to understand how the music became of interest to such a large group of Japanese people, I asked Akira Otsuka how he first discovered bluegrass music. His initial response—given with a hearty chuckle—was “How much time we do have?”

Akira then explained that there was a Far East Network (FEN) radio program in Japan that mostly programmed for the American soldiers who were living on military bases there. He said, “We could not hear it that much in the area where we were living—the Kobe and Osaka area. But, the people in Tokyo, they were listening and back in the 1950s there was a bluegrass band in Tokyo called the Ozaki Brothers. More than likely, they discovered bluegrass by listening to FEN, the (American) military radio. They, along with rockabilly bands, were playing concerts in halls that seated 2000 people and they were doing very well. Even though their group was short lived, they had an influence on the introduction of bluegrass in Japan. Also, Japanese record companies started releasing American albums, like from King Records, from bands like the Stanley Brothers and Reno &Smiley…and Flatt & Scruggs from Columbia. So, the albums were there. They were expensive, but we helped each other by trading albums and taping.”

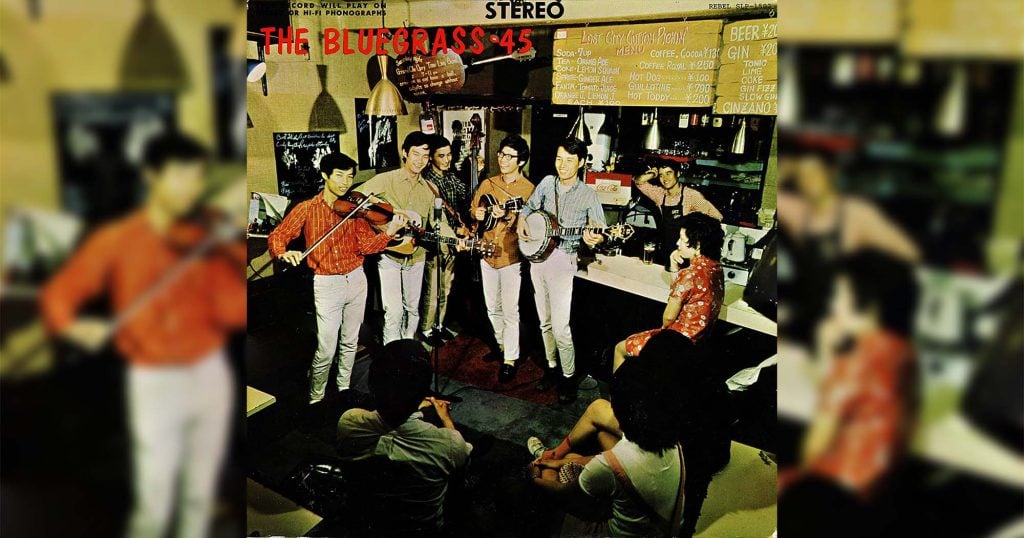

Akira continues, “In our area we did have some records and in Kobe they had an American Folksong Society. They had a monthly get-together. Somebody would bring an LP or two and say, ‘OK, here is a new LP that I bought and it is by the Stanley Brothers. He would play ‘How Mountain Girls Can Love’ and we were just listening. Also, there was a coffee shop in Kobe called Lost City and that is where a lot of us met other bluegrass fans. The big thing back then was also the folk boom and many concerts with folk, country and bluegrass groups. There was a lot of Brothers Four and Kingston Trio type bands. We picked bluegrass because we liked it.”

The Otsuka Brothers

Akira then answered the question in relation to the experience of both himself and his brother Josh (Japanese name—Tsuyoshi), who was also in the Bluegrass 45 band. He said, “We are two of five kids. I am the youngest (born 1948) and Josh is the next one (born 1944). The one older than Josh is Yutaka (born 1941). When he got into college, in 1962, at Momoyama Gakuin University in Osaka, he joined a pop music club. Just about every college had a pop music club. Sometimes they have a Latin band, Hawaiian band, rock-n-roll, jazz, country, or bluegrass band. He didn’t know anything about bluegrass, but he bought a guitar, joined a country band, and started singing. Josh and I played his guitar a little bit while he was not around.”

Akira continued, “When you are a freshman in a college club it means that you set up the amplifiers, tune up the senior’s guitars, set up the drum set and stand back when they come in and start rehearsing. If you are lucky, they let you try one song. When they went on the road, the freshman had to put all of the amplifiers and the drum set on the train. Yutaka didn’t like that. By the time he was a sophomore the country band had disbanded. But by that time he had found a music called bluegrass where each member carries one instrument. So, he got together a bluegrass band called the Bluegrass Ramblers. He let Josh fill in on mandolin, Mitsuo Shibata on banjo, and a classically trained violinist—that didn’t know anything about bluegrass—played the fiddle. His name is Shoji Tabuchi and he now lives in Branson, Missouri. He is one of the biggest draws in Branson (editor’s note: Shoji Tabuchi has his own theater in Branson and is known as the “King of Branson”).

“Back then Shoji didn’t know any bluegrass, so Josh taught him. Josh had also taken Suzuki violin lessons for about four years when he was in elementary school. Josh wrote down ‘Orange Blossom Special’ for Shoji. He only had to look at it once and he had it.

“Yutaka had started bringing a lot of bluegrass albums home. If he was borrowing it, we taped it. That is how we learned. Also, there was a radio station, Radio Osaka, that had a DJ named Yukihiro Hamazaki that had a two-hour show every Tuesday night from 11:00 to 1:00. From 11:00 to midnight he played country music, but from midnight to 1:00 he played bluegrass. I was listening to it every week when I was in high school. I wrote down every song that he played. I also wrote a postcard to him requesting a song every week so that I could hear what I wanted to hear and also to support the bluegrass program.” The Bluegrass Ramblers band lasted at Momoyama University for fifteen years and they won the National Championship twice at the Coca Cola sponsored All-Japan College Band Contest.

Bluegrass 45

The Lost City coffee house, in Kobe, was managed by a Japanese banjo player Kenji Nozaki. The main attraction at the coffeehouse was Kenji’s band, which included Shoji Tabuchi on the fiddle. In the spring of 1967, two of the band members were scheduled to travel to the United States, but Kenji needed a band to fill in at the coffeehouse while they were traveling. Kenji recruited some young musicians who were hanging around the coffeehouse and asked them to keep the live music going. They were the Otsuka brothers (Josh on guitar and Akira on mandolin) and the Watanabe Brothers (Toshio Watanabe on bass and his half-brother Saburo Watanabe). The band was completed with two Japanese-Chinese individuals who both had a Chinese father and Japanese mother—Hsueh-Cheng Liao on fiddle and Chien-Hua Lee on rhythm guitar. They named the band Bluegrass 45, taking the name from “Train 45,” Colt 45, and 1945, the year that Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs joined Bill Monroe’s Bluegrass Boys.

At Lost City the band became popular because they could speak English and thus could communicate with customers who came in off of US Navy ships and cruise ships that docked in the port town. The band was also very adept at taking requests. Akira said, “Josh remembered a lot of songs and his English was much better than the rest of us. The advantage that we had over the other bands, who were mostly college bands, was that they were not used to entertaining the crazy sailors.” To help promote themselves, they would head down to dock when a Navy vessel or cruise ship would come in and hand out flyers that said, “Come on into the Lost City—listen to country music and have a ball.”

The band recorded their first album late in 1969 because a few of them were going to graduate college in the spring of 1970 and they thought that would be the end of the band. They self-financed the recording and tracked the record, titled Run Mountain, at the Osaka Municipal Music Hall. The album was released in 1970. Dave Freeman, of County Sales, heard the recording and said, “It’s a very good job and I enjoyed it very much. I think it is definitely the best non-American bluegrass album that has been issued anywhere so far.”

In the next segment of this article series, we will begin to present notes from Akira’s journals and you will discover how the band ended up getting booked on their 1971 US tour.