Home > Articles > The Archives > The Goins Brothers: Melvin and Ray—Maintaining The Lonesome Pine Fiddler Tradition

The Goins Brothers: Melvin and Ray—Maintaining The Lonesome Pine Fiddler Tradition

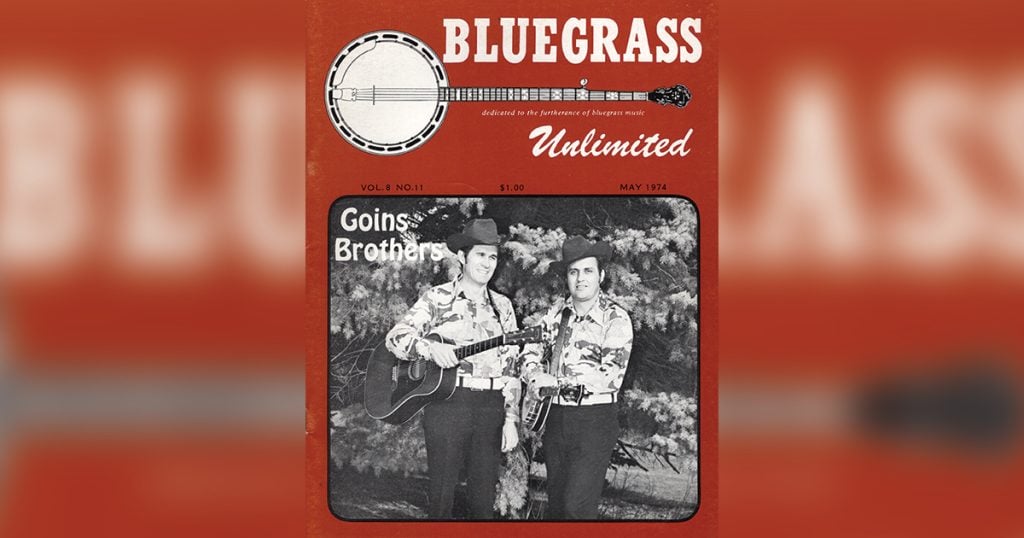

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

May 1974, Volume 8, Number 11

In the early years of bluegrass, a large number of combinations rather quickly took up the style being popularized by Bill Monroe and his band. While it is true that most of the elements of the bluegrass style had been around for several years and various bands had unconsciously used portions of the emerging sound, after 1945 many made conscious efforts to emulate the Blue Grass Boys by adapting their style to their own material. Most prominent among these were the Stanley Brothers and after 1948 Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs. Somewhat less prominent, but nonetheless a long established group with a distinct style were the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers, who bluegrass scholar L. Mayne Smith considered one of the ten major groups when he wrote his pioneer study of a decade ago.

Unfortunately for those of us who had become hard core bluegrass fans only in the last decade, the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers no longer exist as a group. They never played any college concerts and disbanded before bluegrass festivals became numerous. Through most of their career they played to audiences in the small towns and coal camps of Appalachia. Likewise their records, although cut primarily on major labels, received fairly limited distribution, both in the early fifties on RCA Victor, and a decade later on Starday. Regrettably, only two sides have been re-released in the United States. Nonetheless, several bluegrass musicians prominent on the current scene worked with that now legendary group. Most notable among these are Curly Ray Cline, now an eight year veteran of Ralph Stanley’s Clinch Mountain Boys who has managed to inject his own personality upon the bluegrass public to a greater degree than most other expert sidemen, Billy Edwards, Bobby Osborne, Udell McPeak, Paul Williams and Melvin and Ray Goins. It is through the Goins Brothers that much of the distinct vocal and instrumental sound of the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers survives to delight the ear of the contemporary bluegrass fan.

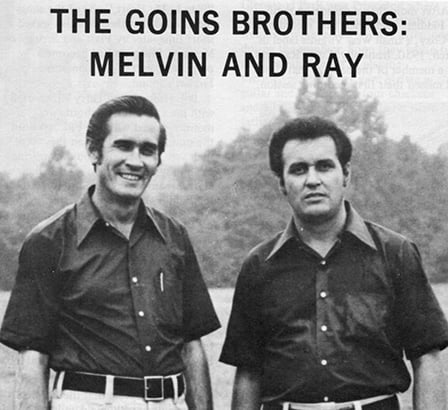

Melvin Goins, lead singer, rhythm guitar player and spokesman for the Goins Brothers was born near Bramwell, Mercer County, West Virginia on December 30,1933. Ray Goins is two years younger, his birthdate being January 3, 1936. There were a total of ten children in the Goins family, most of whom played or sang old time or country music. Both of their grandparents played banjo and other relatives played the fiddle. Although only Melvin and Ray have been long term professionals, one brother, Donnie, played drums for quite some time with country singer Mel Street, and younger brothers, Harold and Conley, play bluegrass, and have appeared at a few shows and festivals with Melvin and Ray.

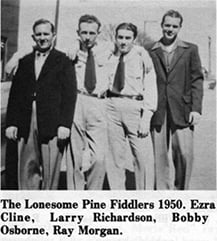

The Lonesome Pine Fiddlers got their start as a band in 1938, a time when the Goins Brothers were hardly out of the cradle. The Cline family of Gilbert, West Virginia formed the nucleus of the group, the leader being thirty-two year old Ezra Cline on bass; and the other members being Ned Cline, tenor banjo; Curly Ray Cline, fiddle; and Gordon Jennings, guitar. The group got their start in radio as a guest on the Lynn Davis show at WHIS in Bluefield and soon had their own show on the station. Bluefield was some fifty miles from the Cline home which meant rising in the wee hours of the morning in order to make it to the studio. During the war, the scarcity of fuel caused the band to abandon their radio show although those who were available played for dances and local social events around Gilbert. Ned Cline was killed in World War II and younger brother, Charlie who played several instruments, joined the band. (Note: Curly Ray, Ned and Charlie Cline were brothers, while Ezra was their cousin). Jennings also left the group to play on numerous radio stations around the country although he later returned to Bluefield with his own radio show. In 1945, the Fiddlers returned to Bluefield with a daily show for Black Draught. The band’s sound although somewhat traditional in nature was not what would be called bluegrass. In November, 1949, Bob Osborne on guitar and Larry Richardson on banjo joined the group giving the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers their first bluegrass sound. Bob Osborne recalled the band’s sound prior to that time as resembling that of the Delmore Brothers (BU, Sept., 1971).

After more than a decade on radio, the Fiddlers made their first recordings for Cozy, a small West Virginia label in March, 1950. Ironically, Curly Ray was not a member of the band at that time and missed their first recording session. “Pain In My Heart,” one of the songs recorded at that time was also waxed a short time later by Flatt and Scruggs on Mercury. Bluegrass had become a permanent part of the Lonesome Pine Fiddler’s sound.

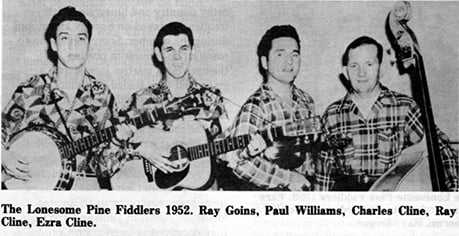

Bob Osborne and Larry Richardson, with the exception of about two months, stayed with the Fiddlers until the summer of 1951, when they went their separate ways: Bobby organizing the Sunny Mountain Boys with Jimmy Martin (who also played briefly with the Fiddlers) and Larry moving on to WCYB in Bristol. In the meantime Ezra recruited new members for his band, Paul Williams, lead vocal and guitar, and Charlie and Curly Ray Cline also rejoined the band when the Sunny Mountain Boys temporarily dissolved that fall. By this time, Charlie Cline was playing the three-finger style banjo. Not long after that Charlie left to play fiddle for Bill Monroe and sixteen year old Ray Goins got his first professional job with the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers.

During the years that the Fiddlers were playing at Bluefield and going through their numerous personnel changes, Melvin and Ray Goins were maturing through childhood, adolescence and adulthood. In addition to the usual work and school activities of rural youth, the boys listened to the music played by various kinfolk. On radio they listened to the Grand Ole Opry where their favorite performer was Bill Monroe and to such local performers on WHIS as the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers and Rex and Eleanor Parker. From about 1947 on, however, their favorite station was WCYB in Bristol where they could hear the Stanley Brothers, Curly King and the Tennessee Hilltoppers, and at various times Charlie Monroe, Mac Wiseman, and Flatt and Scruggs. The brothers also got to see some of their favorites at the Glenwood Park near Princeton where many country and bluegrass artists frequently played on Sunday afternoons during the summer. Soon they began to manifest an interest in playing themselves. A relative gave Melvin a guitar and they traded four chickens and a rooster for a banjo. Later their father swapped the banjo in a horse trade and the brothers replaced it by a week’s hard labor at basement digging. With the proceeds of their toil they purchased a new banjo at a music store in Bluefield. When free from their chores, the boys spent hours practicing in an isolated mountain cabin. In 1950 and 1951, they occasionally guested on Gordon Jennings’ radio show on WKOY in Bluefield.

Ray Goins played several months with the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers in 1952 and was present for the band’s first two sessions on RCA Victor.

Others in the band included Ezra, Curly Ray and Paul Williams with Rex Parker helping out on mandolin. “My Brown Eyed Darling,” was perhaps their most popular number from their 1952 sessions, being composed by Ezra’s daughter, Patsy, with the assistance of Paul Williams as a tribute to her fiance, Bobby Osborne, then in the U.S. Marines. After leaving the Fiddlers, Ray, together with Melvin, Ralph “Joe” Meadows and Bernard Dillon, a distant relative, organized the first Goins Brothers band and also played a daily radio show at WHIS. This group played from August to November at Bluefield.

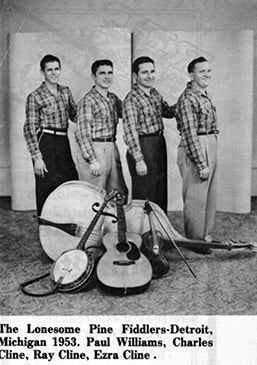

In the fall of 1952, the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers moved from Bluefield to WOAY in Oak Hill; and then the following January, after some fifteen years, they left West Virginia. For most of 1953, the Fiddlers played at WJR Detroit, Michigan on the Big Barn Frolic. They played numerous shows in Michigan and also in adjacent states and Ontario, Canada. During this time the Fiddlers cut another session on Victor in Chicago. One of the songs from this session, “Dirty Dishes Blues,” penned by Gene Masters of Cincinnati, became popular. At this session, Albert Punturi, a relative of Ezra’s helped out on mandolin. They also provided the musical backing for an upcoming country duet on the Fortune label known as the Davis Sisters, composed of Betty Jack Davis and Mary Frances (Skeeter) Penick. Their later RCA Victor record of “I Forgot More Than You’ll Ever Know” became one of the greatest country hits of the early fifties although the duo came to a tragic end in August when Betty Jack Davis was killed in an auto wreck. Skeeter Davis, however, has since become a success in the country field, and has remained a dedicated bluegrass fan.

In early November the group that had worked at Detroit broke up. Paul Williams left the band to enter the service and Charlie Cline rejoined Bill Monroe. Ezra then contacted the Goins Brothers who joined him and Curly Ray in mid-November, 1953 at WLSI in Pikeville, Kentucky. Fiddler Joe Meadows shortly afterward moved to Bristol joining the Stanley Brothers band. Some twenty years later he would be reunited with the Goins Brothers.

For the remainder of their existence, the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers continued to be based in Eastern Kentucky. Like southern West Virginia this region lies in the heart of what has come to be called Appalachia. It is a land of rugged topography, narrow, crooked roads and numerous small towns, most of which are (or have been) coal camps. Today, it has become known to the outside world as an area of grinding poverty, cultural backwardness and corporate exploitation. Despite this bleak picture, life in Eastern Kentucky has enjoyed its moments of happiness — perhaps as many, if not more, than more affluent parts of the world. Among other enjoyments the inhabitants of those towns were treated to frequent shows by such groups as the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers. The Fiddlers continued to play their daily radio show at WLSI for several years. Their sponsor paid the fabulous sum of fifty dollars per week which they evenly split four ways.

Their main source of income, however, was derived from a variety of live appearances at both indoor and outdoor theaters, matinee and evening performances in schoolhouses, and the so-called “candy show.”

Even today, the Goins Brothers play numerous day time shows in that region’s elementary schools during the winter and drive-in theaters still book bluegrass and country shows although such things are no longer done much elsewhere. However, that form of entertainment, the “candy show,” commonly used by the Fiddlers in the fifties no longer flourishes in Appalachia or anywhere else. One might describe the candy show as something like a medicine show only for the consumer with a sweet tooth rather than an ache or pain. Melvin describes it thusly: “It was a free show … we would do into these little communities and play these little ball parks, fields, close to country grocery stores — any place where we could find a big place in the road where we could assemble a lot of people for a big free show. We had what they call a candy show and we done [sic] free entertainment and sold candy for a quarter a box and gave away gifts and prizes [in the candy box]. The Fiddlers announced the locations of their forthcoming candy shows on their radio programs and also promoted it in the particular community by loudspeaker on the day of the performance. Ezra Cline recently recalled that the crowds were generally large, as many as a thousand persons and that they sometimes remained for several days in the same location if attendance remained high. The financial rewards, while not great by modern standards, compared favorable with the shows where admission tickets were sold. It was also at these outdoor shows that the Fiddlers first used a sound system having performed in the early years without the aid of a PA set.

In 1954, the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers did their final two record sessions on RCA Victor in February and September, respectively. In addition to Ezra, Curly, Melvin and Ray, James Roberts played mandolin on these sessions. Roberts, sometimes known as James Carson, was the son of the Doc Roberts, the famous old time fiddler and pioneer recording artist. Some years before he had recorded several outstanding gospel duets on the Capitol, White Church and Rich-R-Tone labels with his wife, Martha Carson. Four numbers were recorded at each session. Of these, “Windy Mountain” and “No Curb Service” are currently available on Victor’s anthology album Early Bluegrass (LPV 569). Despite the lack of original material reissued in this country, most of the band’s twenty-two sides for Victor have been released on Japanese albums. The session of September, 1954, was to be the last recordings by the group until 1961 when they went to Nashville to record for Starday. Most of the Victor recordings were original material, several of which were penned by Curly Ray Cline, Paul Williams or Keisler Cline. Unfortunately, Curly’s recent success as a fiddler and festival performer seem to have obscured and subordinated his talents as a songwriter.

The foursome of Ezra, Curly, Melvin and Ray continued to work together as the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers until April of 1955 when Ray departed for Flint, Michigan, and a GM plant. Melvin stayed until June and then he too left the group. As replacements, Ezra hired first Udell McPeak and then Billy Edwards. After his return from the service, Paul Williams rejoined the Fiddlers for a brief time before going with Jimmy Martin. Although this combination made no recordings, they undoubtedly made some excellent music and played a weekly TV show at WHIS in Bluefield for Piggly Wiggly Stores as well as their radio work in Pikeville. Udell McPeak, who even today possesses a wit and sense of humor virtually unsurpassed among bluegrass musicians, also played a costumed comedy role, that of “Jasper.” During this period Ezra published a Lonesome Pine Fiddlers Song and Picture Book which has today become a treasured collector’s item.

When Melvin Goins left the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers he soon got back with Ray who had returned from Michigan, and the brothers again formed their own group with their uncle, Bernard Dillon and cousin, Clyde “Buck” Dillon. From July until November, they played a half-hour daily radio show at WPRT in Prestonsburg, Kentucky. With winter coming on, as Melvin puts it “got a little cold and times got hard,” and the band dissolved. After working at various odd jobs throughout the winter, the brothers returned to Bluefield in the summer of 1956. Melvin, who had married in June of that year, sought more substantial employment. He found it at WHIS-TV with Cecil Surratt.

During the next few years, bluegrass music went through a difficult period because of the impact of rock and roll. Even in Appalachia, traditional country groups found it necessary to make some accommodation, an electric guitar becoming the minimal addition. For the next couple of years until late 1958, the Goins Brothers worked as part of Cecil Surratt’s group on his daily afternoon television show and also on Saturday night. Smitty Smith soon joined the entourage on electric guitar. They also worked a Friday evening jamboree on WOAY-TV at Oak Hill and played numerous personal appearances and dances through the region. After Billy Edwards left the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers he came to Bluefield where he was already known through his television appearances with Ezra’s band. Billy’s versatile talents were used in a variety of ways until Ray Goins again quit music for a time to work in a furniture factory at Bluefield, after which Billy played banjo.

The Lonesome Pine Fiddlers also changed their style somewhat in response to the times. Through much of the later fifties, they used electric guitar played by Charlie Cline. Lee Barnett, Charlie’s wife, was featured on vocals, along with the ever present Curly Ray and Ezra. During much of 1958, they played a weekly half-hour show at WSAZ-TV in Huntington along with their radio work at Pikeville.

About 1960 or 1961, Charlie Cline left the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers for the final time and entered the ministry. He is now located in Alabama. Shortly afterward Melvin and Ray rejoined Ezra’s band. The Fiddlers began to record again, this time for Starday and had three albums released in the next two years. They did a fourth album with Hylo Brown and he in turn helped out on their last album (Starday 222 More Bluegrass) which was cut at the same session. For about fifteen months Ezra, Curly, Melvin and Ray worked at WCYB-TV in Bristol where they had a show on Monday evenings. This foursome remained together until 1964.

By this time the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers were becoming a part-time group. Ezra Cline had already entered the restaurant business in Pikeville some years before and also operated a swimming pool during the summer months. Curly Ray did some work in the mines and so did Ray Goins until he acquired a grocery store. Curly and Ray also helped local artists on occasional recording sessions including Hobo Jack Adkins (original composer of “No School Bus in Heaven” recorded both by the Stanley Brothers and Red Ellis). However, throughout the mid-sixties they continued to play a few school matinees and dances. Kentucky Slim (Eddie Branham) played guitar in this latter period.

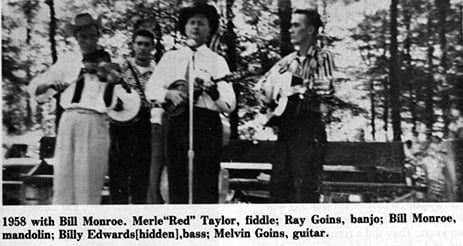

Melvin Goins, together with Billy Edwards, Louie Profitt on fiddle, Norman Blake on Dobro, Bill Lowe on bass and sometimes Ray, worked a lot of package shows at parks, drive in theaters and schools. Often they appeared with other name acts such as the Louvin Brothers and the Osborne Brothers. They worked one memorable show with Bill Monroe; at the time one of the Blue Grass Boys, Ed Mayfield was stricken with what proved to be a fatal illness. The assistance of the Goins Brothers and their band at this time helped to cement Melvin and Ray’s lasting friendship with Bill Monroe.

Most of the time, however, this group worked with Hylo Brown and Melvin did the booking for Hylo for a couple of years. Norman, Billy and Louie worked on Hylo’s last session for Capitol records. Unfortunately, this material has never been released The Lonesome Pine Fiddlers did not actually disband until 1968 when Ezra Cline retired from the restaurant and moved back to West Virginia. Today, he lives at Baisden, a small community near Gilbert and is active in the local Community Action program. Even yet he is not wholly out of music and sometimes emcees a show in the area or plays with local musicians. He keeps up with the contemporary bluegrass scene, particularly the activities of the Osborne Brothers.

When they left the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers in 1964, Ray dropped out of music for a time except for part-time work with the Fiddlers; Melvin stayed in the business. He worked some as a single, played with Hylo Brown, and a few other groups part time. In January of 1966, Melvin booked some shows for the Stanley Brothers and shortly after joined the Clinch Mountain Boys full time. In this period he played rhythm guitar and bass, and did comedy while also helping out with bookings. After Carter Stanley’s death in December, 1966, Melvin remained with Ralph’s Clinch Mountain Boys for two and one-half years. He participated in Ralph’s early recording sessions on Jalyn and King, playing rhythm guitar and singing bass or baritone. Much of the time he appeared in the comedy role of “Big Wilbur.” He left Ralph’s group to reform the Goins Brothers in May,1969.

While Melvin worked for Ralph Stanley, Ray had been operating a country store near Elkhorn City, Kentucky. One of their first moves was to record on the Rem label entitled Bluegrass Hits – Old and New with the able assistance of Paul “Moon” Mullins on fiddle and Kentucky Slim on bass. Harley Gabbard of New Trenton, Indiana soon joined the group on Dobro for most of their shows and Kentucky Slim played bass, lead guitar (and occasionally the spoons).

In 1970, the Goins Brothers added Dave Sutherland, formerly of Jim and Jesse’s Virginia Boys on bass. Ricky Skaggs, who later played with Ralph Stanley and the Country Gentlemen as well as recording two fine albums with Keith Whitley worked a few shows with the boys that summer. They also did a recording session on Jalyn in May from which a single, “Pistol Packin’ Mama/Fly Little Bluebird” was released quickly and an album Bluegrass Country, somewhat belatedly. This album while of good vocal quality received some criticism because it had neither a fiddle nor a mandolin on the instrumentation. Melvin and Ray also played a large number of festivals that year and have since become one of the most frequently seen groups on the festival circuit. They played a half-hour show on WKYH-TV in Hazard, Kentucky on Tuesday evenings and frequently guested on the Sleepy Jeffers show on WCHS-TV in Charleston, West Virginia. In 1971, they initiated their own festival at Lake Stephens Park near Beckley, West Virginia which has shown steady growth and shows promise for continuing success.

The Goins Brothers began recording for the Jessup label in Jackson, Michigan, in late 1971. To date, they have had two albums released. The first album Head of the Holler featured quite a bit of new material, much of it composed by Mike Paxton, a deejay friend of the boys from Pikeville, Kentucky who had earlier written “Fly Little Bluebird,” one of the boys more popular numbers. Art Stamper of Louisville, Kentucky, a veteran of the Stanley and Osborne bands, fiddled on this session and his presence contributed greatly to the album’s musical success. Leslie Sturgill played mandolin on this album (although he played bass on most shows) and Bill Rawlings, formerly with the Twin River Boys and more recently with Jimmy Gaudreau and The Country Store played bass.

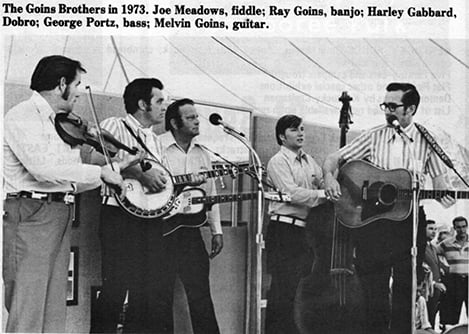

The February session for Jessup which resulted in their best recorded effort to date also led to the acquisition of their most outstanding sideman to date. An accident prevented Art Stamper’s working on that session and as a substitute they obtained the service of Joe Meadows of Princeton, West Virginia, who had first played with the boys some twenty years before. Joe had gone on from those lean days at WHIS to make many great recordings with the Stanley Brothers on Mercury and to have also played with Bill Monroe among others. However, at the time he had not played full time for several years although he had played at some fiddler’s conventions and with some West Virginia bands. The trip to Michigan in January led to Joe’s joining the band full time in May. His fiddle has added considerably to the Goins sound giving it a degree of fullness that it had sometimes lacked. Joe’s services have also come in greater demand as he recently helped Larry Sparks on a session. Another new addition to the group last year, George Portz, plays bass fiddle, replacing Leslie Sturgill.

Besides their frequent festival appearances the Goins Brothers still play a great deal in eastern Kentucky. The candy shows are gone, but they still play a lot of daytime shows in area elementary schools. Although this may seem an anachronism in some respects, it also serves a cultural purpose by helping to preserve the musical heritage of an area rich in tradition, that may be lacking in the more worldly forms of wealth.

The Goins’ repertoire has come primarily from three sources to date. Bluegrass standards, new traditionally oriented material like the Mike Paxton compositions, and Lonesome Pine Fiddler songs constitute their main fare. It is perhaps with the latter material that they are at their best. The Lonesome Pine Fiddlers left a rich musical tradition which two of the junior members of the band — Melvin and Ray Goins — are continuing with competence.