Melvin Goins

From the Hall of Fame Lonesome Pine Fiddlers to the Goins Brothers, He Lived the Hard Life of Bluegrass

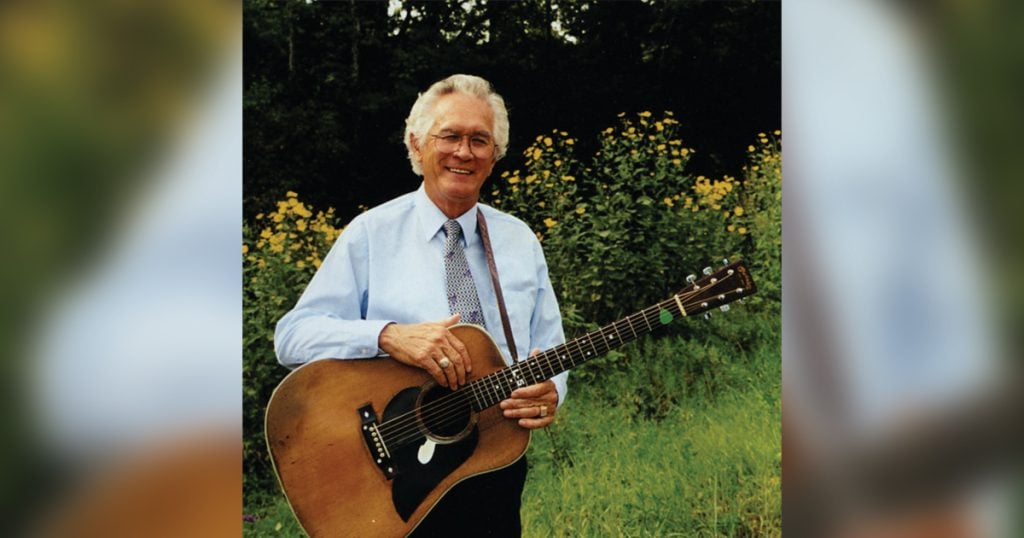

Melvin Goins was a regular at the now-defunct Appalachian Uprising music festival held in Scottown, Ohio, just across the river from Huntington, WV. Goins was in on the formative talks about the creation of the event, giving festival owner Steve Cielic his advice after having lived a legendary bluegrass life.

The Appalachian Uprising was a convenient gig for Goins as he lived just 25 miles away with his wife and horses in Catlettsburg, KY, just across the West Virginia border.

In 2008, one year after Goins’ brother and musical partner Ray Goins passed away in July of 2007, Vince Herman of Leftover Salmon is onstage at the Appalachian Uprising with the band Great American Taxi. In-between songs, in a wonderful moment of respect, Herman mentions and honors the late Ray Goins to the crowd from onstage, then turns his head and keeps his gaze on Melvin until he looks him in the eye and nods his head in return.

Beginning in the mid-1950s, Melvin and Ray Goins played some of the best traditional bluegrass music to ever come out of the Appalachian Mountains. The Goins Brothers Band was a mainstay in the genre, except for a couple of breaks that would make bluegrass history.

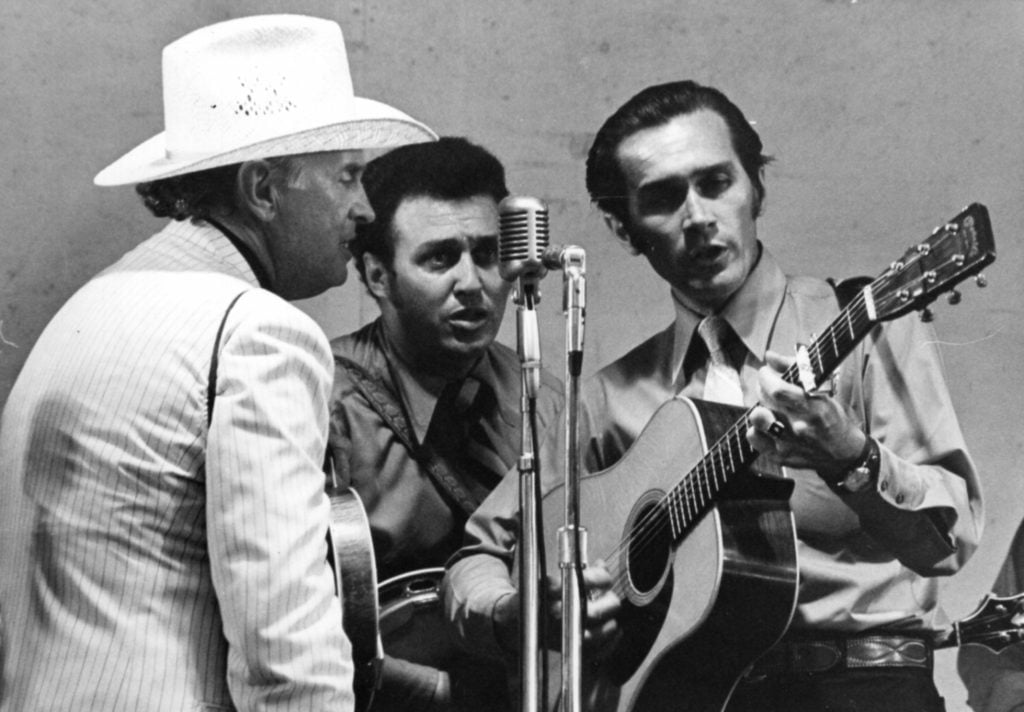

In 1951, Melvin and Ray Goins were asked to join the future Bluegrass Hall of Fame band the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers. Still very young men, the brothers performed on radio and recorded some of the best, most under-rated bluegrass music ever captured with the group.

One fascinating aspect of the history of the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers is they began as a family band featuring the Cline Family in 1938, meaning they were ripping string band music on the air in West Virginia several years before Bill Monroe and Earl Scruggs and crew solidified bluegrass as a new genre in 1945.

Melvin Goins was five years old and Ray was two years old when Ezra Cline and his cousins Lazy Ned Cline and Curly Ray Cline began performing as the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers along with guitarist and announcer Gordon Jennings. Eventually, the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers left their radio show on WHIS in Bluefield, WV, and would move to Pikeville, KY, where they made their bones with a legendary radio show on WLSI as well as TV appearances on WSAZ in nearby Huntington, WV. Other notable members of the band back in the day included fellow future Bluegrass Hall of Famers Paul Williams and Bobby Osborne.

In 1953, the younger, more bluegrass-influenced Goins Brothers joined the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers in Pikeville. After recording some wonderful sides for various record labels, the Goins Brothers then left to form their own band in 1955. Melvin and Ray would rejoin the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers in 1961, however, recording four great albums featuring Hylo Brown on one recording.

Then, Melvin decided to join the Stanley Brothers just 11 months before Carter Stanley died at 41 years of age in 1966. After that short stint, however, the Goins Brothers would reunite and tour until Ray’s health caused him to retire in 1997. Melvin continued on, sponsored by guitar luthiers the SAGA Musical Instruments company and continuing to record and perform as Melvin Goins and Windy Mountain until his death in 2016.

In this article, we are going to explore the life of Melvin Goins by bringing new facts to life, combining a couple of interviews I did with him before his death in 2016 and digging deep into the newspaper archives where his career was captured in real time going back 60 years.

Melvin Goins grew up outside of Bluefield, WV, in the heart of the Great Depression of the 1930s when life was not easy. He was the eldest of 10 kids.

“Our daddy was a coal miner,” said Goins. “My first job, instead of working in the mines, I went to work at a big feed house in Bluefield called the Farm Bureau. There wasn’t a lot of money in it, but it was my first job. I got about four dollars a day. I worked for forty cents an hour and worked about ten hours a day there. That was back when I was about 16 years old. I had to go to work because my Dad came down with heart problems and he couldn’t work. I was the oldest boy, so that is why I had to quit school to go to work and try to help feed the family. It wasn’t a lot of money, but anything is good when you got nothing.”

There is a real good chance, obviously, that the very young Melvin Goins heard the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers on the radio in Bluefield from 1938 on. But when you get into the early history of that group, there is more to the story of the early Lonesome Pine Fiddlers that is found in the newspapers of the day.

Though it is stated that the Cline family formed the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers in 1938, while doing research, all of a sudden I find the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers listed as performing on the radio in Lexington, KY, in 1936. Intrigued, I decided to research further.

In Lexington, Kentucky—about 200 miles from Bluefield as the crow flies—the Lexington Herald newspaper of January 3, 1936, publishes the radio show lineup for the day on WLAP, which at the time was found at 1420 on the AM dial. Amongst other shows found on the station, such as daily programs by the Devano Trio, the Morning Housewarmers, Livestock Reports, the Matt Adams String Ticklers, Uncle Henry’s Mountaineers, Tonic Tunes, Saxton and Nugent, the Cowboy Singers and the Paul Cornelius Orchestra, there are two radio shows by the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers at 10 A.M. and 5 P.M.

So, I keep researching and find the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers on the radio listings as early as 1935, three years before their official starting date per their Bluegrass Hall of Fame biography. Then, I come across a clue when I find an ad for a live concert in the Lexington Herald on May 31, 1936. At a place called Joyland Park, amongst other shows by swing jazz great Don Redmon and Andy Anderson and his Student Prince Orchestra, there is a square dance hosted by “Si Rogers and his Lonesome Pine Fiddlers.”

As it turns out, there was already a group called the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers headed up by Silas Rodgers, and the kicker is that it was this band that introduced banjo player David “Stringbean” Akeman to the world. Stringbean, of course, would so go on to join Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys in 1943, only to be replaced by Earl Scruggs two years later.

As for Melvin and Ray Goins, their first mention as “The Goins Brothers” that I found in a newspaper came in the Hinton Daily News in Hinton, WV, a railroad town at the southern end of the New River Gorge.

On Page 1 of the Hinton Daily News on September 3, 1960, there is an article about the newly-formed communist Cuba. The new Premier Fidel Castro had just recognized communist China, then regarded as a blatantly anti-U.S. move, and the bearded leader took a copy of the 1952 bilateral United States-Cuban Defense Treaty and ripped it up and “tossed the fragments to 300,000 wildly cheering Cubans on Friday night.”

In the other front page article located right next to the update from Cuba, there is news of West Virginia politicians visiting a family reunion seeking support. Family reunions were and are a big deal in the Mountain State. In this case the article says, “One of the state’s largest family reunions will be held at Lockbridge Sunday when the Quinn clan will open its annual meeting.” The politicians taking advantage of this big get-together of 5,000 people include U. S. Senator John Randolph, Governor Cecil Underwood and Republican gubernatorial candidate Harold E. Neely. This happened six months after John F. Kennedy famously visited West Virginia on his way to becoming the 35th President of the United States in November of 1960.

Amidst this familial and political gathering were sets of live music. Says the article, “During the morning and afternoon programs, the musical groups scheduled to appear include the Christian Four Quartette and the Goins Brothers String Band.”

Fast forward 13 years later to 1973 and the Goins Brothers are still at it, yet from their comments in an article that year in the Courier-Journal and Times newspaper in Louisville, KY, they are sadly still on the lookout for success.

“The bluegrass beat gains notice and sends Goins Brothers happily to the verge ‘of making it big,’” reads the kicker. Helping the band out, of course, was the release the year before of 1972’s Will The Circle Be Unbroken album by the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. That special guest-laden, three-album project gave bluegrass music a big boost.

Written by Ward Sinclair, the article includes a conversation with Melvin and Ray Goins along with, of all people, Indiana resonator guitar great Harley Gabbard, who was playing with the Goins Brothers at the time. The opening paragraph sets the tone of the piece.

“The nights are long and lonely, the back seat in the station wagon is always too hard and they’re always a million miles from home, but the Goins Brothers keep on going,” writes Sinclair.

As the interviews unfold, all three musicians are in the mood to tell it like it is, as far as being a bluegrass musician during that time period. As always, Melvin’s sense of humor is present.

At the time of the article, the Goins Brothers band had just performed at the prestigious Smithsonian Institution’s Festival of American Folklife, appearing live and on national TV and radio. Sinclair describes this musical period as the nation being “in the throes of a massive bluegrass binge.” “Bluegrass records are selling like hotdogs,” adds Melvin, “although we’d rather they sold like records.”

That is when Sinclair brings it down to reality, talking about previous years when “concerts were played for next to nothing and most people couldn’t care less whether they heard one of those whiney hillbilly bluegrass ensembles.”

Melvin is booking the band at this point in history, and he talks of lining up gigs so they can make room for appearances on the Grand Ole Opry. Brother Ray then chimes in.

“Bluegrass is going big right now,” says Ray. “Anybody who doesn’t make it in the next five years can forget about it. But, I think bluegrass is going to grow bigger and bigger. If I didn’t think I could make a go of it, I wouldn’t stay in it. The college kids have done a lot for bluegrass. A lot of them have learned to play and a lot of them are picking these days. We play a combination when we do a concert, playing bluegrass and even a lot of country numbers. It gives people variety, which they like, but it is good to have new ideas.”

The members of the band then talk about the need for new songs, and that is when an interesting reference happens. It is noted in the article, for you current bluegrassers always looking for songs to record, that at that time the Goins Brothers had recorded 10 new songs written by chief engineer Mike Paxton of the Pikeville radio station WLSI. Apparently, Paxton had 90 more original songs left in his songbooks at the time.

As the article progresses, Gabbard tells it like it is, saying, “We’ve struggled long nights, and we’re not interested in getting rich, but even if we make big money in the next ten years, we still wouldn’t break even for all of the time we’ve spent.”

Three years later in 1976, the Goins Brothers are interviewed in the same newspaper, this time by columnist Billy Reed. The group is about to make an appearance at the fourth annual Bluegrass Music Festival of the United States held in Louisville. In this exposé titled “Second fiddle no more, the Goins Brothers have come a long way,” Melvin is in the mood to talk about his upbringing with brother Ray.

“We’d come in out of the cornfields to eat our dinner and we’d always listen to bluegrass music on this little bitty ole radio we had,” said Melvin. “The Stanley Brothers were on there all of the time and so was Flatt and Scruggs, Curly King and the Tennessee Hilltoppers and lots of others.”

Looking back to when Melvin was a teenager becoming interested in music, he tells the story of getting his first guitar from his cousins and eventually trading four hens and a rooster for an old banjo with a local railroad conductor. With two instruments now in their hands, the Goins Brothers found a picking partner with their coal mining cousin Tracy Dillon.

“We had to walk two miles up a dirt road to get to his house,” said Melvin, in the article. “We’d go up there at 6 or 7 of an evening and not leave until 9 or 10. In the winter, it was hard, but he learnt us to play old-time fiddle tunes.”

Melvin also admits in the piece that even during the best of times with the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers, he had to do farm work to keep his head above water financially while Ray ran a grocery store in Pike County, KY.

The members of the Goins Brothers band during this period included their 21-year-old younger brother Conley Goins on bass, Buddy Griffin on fiddle and Curly Lambert on mandolin. They were also producing new albums on the Rebel Records label while doing a weekly TV show on WKYH in Hazard, KY. The band also hosted their own festival in the 1970s at Twin Falls State Park located near Beckley, WV.

In an article in the Beckley Post-Herald newspaper on June 20, 1975, the unique features of the 5th annual Goins Brothers Mountain State Bluegrass Festival are described. First of all, the lineup included well-known legends and future IBMA Hall of Famers such as the Osborne Brothers, Jimmy Martin and the Sunny Mountain Boys, Larry Sparks, Ralph Stanley and the Clinch Mountain Boys, Hylo Brown, Paul Mullins and the Boys From Indiana. Lesser known bands on the bill included the Slone Family, Frog and the Greenhorns, Jim Eanes, Harold James and Chip, Rex and Eleanor, the Bluegrass Gospel Boys, the Woodettes Gospel Singers and the Parker Family.

To add to the music, the festival also featured a prize for the oldest coal miner present, a prize for the largest coal miner family at the event and a greasy pole climbing contest.

The Goins Brothers would roll on for another 20 years before Ray’s health unfortunately brought about his retirement. After Ray’s death in 2007, I asked Melvin about the loss of his brother just a few short months after it happened.

“I miss him,” said Goins. “There are things that I can’t do now that I did do when I was with him. A brother act is a close act. Blood brothers. There isn’t anyone that sings like two brothers. Like the Louvin Brothers, Jim and Jesse, the Delmore Brothers, so many of the brother acts, they have a harmony that blends. It’s bloodline. There isn’t anybody that carries that real close harmony like two brothers.”

Sadly, Ray left this world before the Goins Brothers were inducted into the Kentucky Music Hall of Fame in 2011 and into the West Virginia Music Hall of Fame in 2013. That reality is why I was so pleased to see Melvin alive and well when he and Ray were inducted into the IBMA Hall of Fame as members of the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers in 2009. I know that it meant a lot for the whole Goins Family and everybody associated with them.

In 2016, at 83 years of age, Melvin Goins died while on tour in a foreign country as he traveled to the River Valley Bluegrass Festival in Sturgeon Fall, Canada. I always felt sorry for Melvin’s band during this period as their leader was reaching for the Heavens as his physical body was lying on a slab in a hospital in Canada and they had to find a way to get him home for burial. The phone calls to his wife and family had to be hard to make.

The West Nipissing Tribune newspaper in Canada did a fine job of capturing Melvin’s final hours. In an article written by Isabel Mosseler titled “Bluegrass Legend Plays Until His Last Day,” the River Valley Bluegrass Festival organizer Tony DeBoer tells the sad tale.

“Melvin said that he didn’t think he could come up because he was too sick,” said DeBoer. “A little later they called to say they were on their way and they came in on Wednesday night. On Thursday, they were going to do a workshop and he was feeling terrible. I had to go and get him with my golf cart. He came out for the workshop and started into his song and he talked for a bit, because he is such a great storyteller, and then he went into a second song.”

With a paramedic on hand, Melvin completed the workshop and then immediately retreated to his motorhome. The next day, he suffered a stroke and died 1,260 miles from his Kentucky home.

“‘They used a defibrillator, but it was too late,’ said DeBoer with great emotion,” says the article.

Melvin should have stayed home and not made the trip, of course, yet it makes you think of that the part of him that struggled to make a living in the bluegrass world for all of those hard years. Those were times when you did not refuse a good paying gig, and those old ways may have motivated him to get in that motorhome and give the green light to head north.

“Melvin Goins is a true bluegrass pioneer,” said DeBoer, just hours after Melvin’s death. “He started with the original people and he is a legend. I wanted him back here one more time. He loved the River Valley Bluegrass Jamboree.”

One year earlier in 2015, Melvin Goins and his former boss and long-time friend Dr. Ralph Stanley are in Princeton, WV, doing a tribute concert for the late WHIS-AM bluegrass radio host Joe Lively. The Bluefield Daily Telegraph newspaper describes Melvin’s portion of the show this way, “Goins said his age was ‘39 and holding,’ and judging from his performance, he danced, joked and sang more like a 29-year-old.”

When the newspaper finds Melvin backstage, his first words of the interview are clear as a bell. Said Goins, “I’m going to keep performing until the Good Lord calls me home.”

And, that is what Melvin Goins did, showing up for a festival that loved him before making that long journey back to the mountains and foothills that he loved.