Home > Articles > The Archives > Hylo Brown: The Bluegrass Balladeer

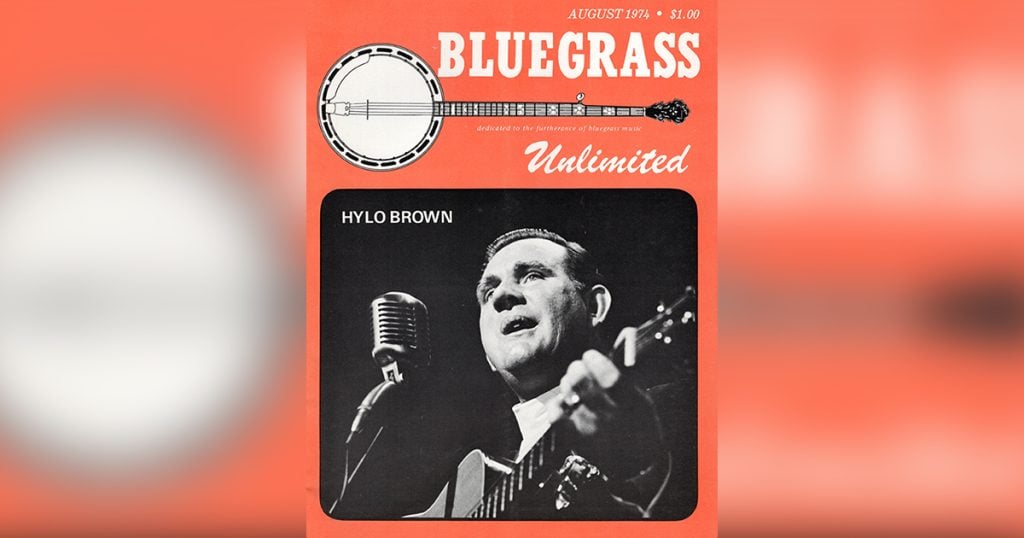

Hylo Brown: The Bluegrass Balladeer

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

August 1974, Volume 9, Number 2

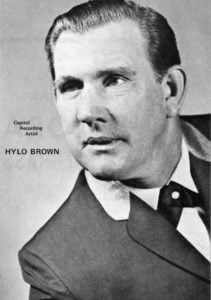

Some two decades ago, a young Kentucky-born factory worker from Springfield, Ohio, went to Nashville, in hopes of getting an established country singer to record a song he had written. Although he had made something of a reputation as a part-time performer around local radio stations and parks, and had once sung tenor on a recording session with a recently retired giant of the industry, he really had no aspirations for a full-time career in music. Much to his own surprise, young Frank Brown soon found himself in the Castle Studio doing a session for Ken Nelson of Capitol Records. In the next few years he would put on wax some of the highest quality bluegrass and hard country music ever recorded. Unfortunately, the trend of the times was in another direction from the style of young Brown and his share of fame would be smaller than that of the Presleys and Cashes who began their recording at about the same time. Nonetheless, for those of us who appreciate the older vocal and instrumental styles, “Hylo” Brown became a popular and significant entertainer.

Frank Brown, Jr. began life at River, Kentucky in Johnson County on April 20,1922. He attended grade school there and then went onto high school in nearby Oil Springs. During these years he began to take an interest in music especially the sound of banjo, mandolin, fiddle and guitar. Like other pioneer bluegrass artists he came to love the sound of the Blue Sky Boys, Monroe Brothers and perhaps somewhat strangely, the Sons of the Pioneers. He was also attracted to ballad singers like Doc Hopkins, Bradley Kincaid, and the Coonhunter of Uncle Henry’s Original Kentucky Mountaineers.

At age sixteen he appeared on radio over station WCMI in Ashland, Kentucky. The next year in 1939, together with Doug Saddler he had a weekly radio show at WLOG, Logan, West Virginia, which paid fifteen dollars. However, this ended with the coming of World War II, an event which helped to accelerate the rural-urban migration. The Brown family constituted part of this movement and young Frank went to work in a defense plant in Springfield, Ohio. After the war he continued industrial work there but also began to play music on area radio stations and at parks.

For years a popular joke has circulated among natives of the Buckeye State that the “three-R’s” as taught in Kentucky consist of “readin,” “ritin,” and the “road to Ohio.” Although economic necessity and industrial employment are obviously the greater factors in this migration, it has resulted in a heavy concentration of bluegrass and country musicians in southwestern Ohio. Among the more popular acts of the late forties was the team of Smoky Ward and Little Eller Long who played WPFB in Middletown after having earlier made a name for themselves at the Renfro Valley Barn Dance. Frank Brown sang on the show with them, but as Smoky had trouble remembering names he began to call the vocalist with the wide voice range “Hi lo” or “Hylo.” The name caught on and the singer with the lonesome mountain sound henceforth became known as Hylo Brown.

Another popular entertainer in the area was Bradley Kincaid, “the Kentucky Mountain Boy,” a veteran singer whose career extended back to the early days of the WLS National Barn Dance and Gennett Records. In 1949, having spent some five years at the Grand Ole Opry, Bradley came to Springfield, purchased an interest in station WWSO, and opened a music store. He performed on his station, played shows and ran a country music park. Hylo Brown was one of several local musicians who worked often with Kincaid during his last years as an active artist and in 1950 when he did his last recording session with Capitol Records before retirement, Hylo assisted singing tenor. Four songs were done at that session in Springfield at the radio station of which “The Legend of the Robin’s Red Breast” and “Red Light Ahead” were best known. Hylo credits his work with Bradley Kincaid as being valuable education in the music business.

Hylo looked upon his early work in music with mixed reactions and sometimes felt more like quitting than continuing. However, Slim McCoy, who played fiddle locally kept giving encouragement and he stuck with it. He also wrote a few songs, one entitled “Grand Ole Opry Song,” which described the show as it existed in the late forties. Merle Travis was on the verge of recording it, but Opry officials were unenthusiastic at that time and the song went unrecorded until Jimmy Martin picked up the song a few years later and waxed it on Decca.

Hylo continued playing in southwest Ohio and dabbling in song writing until late 1954 when he came up with a song entitled “Lost to a Stranger.” Tommy Sutton, a Dayton dee jay suggested the song had possibilities and he took it to Joe Allison in Nashville who believed it fitted Kitty Wells’ style and that she might record it. However, Ken Nelson preferred that Hylo do the song himself for Capitol and quickly arranged for a recording session. The next day Nelson assembled Merle “Red” Taylor, Joe Drumwright, Gordon Terry (on mandolin) and Cedric Rainwater in the Castle Studio and Hylo Brown became a Capitol recording artist. Four songs were cut that day including “Lost to a Stranger” and “Lovesick and Sorrow,” which has also become a bluegrass classic.

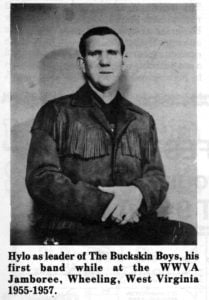

Deciding that now was the best time to go into the business in earnest with “Lost to a Stranger,” meeting a good response, Hylo got a band together and talked his way into a regular spot on the WWVA Jamboree in Wheeling. His band called the Buckskin Boys consisted of Sonny Collins on fiddle, and the Shepherd Twins on mandolin and banjo. Smoky Pleacher played bass fiddle and did comedy for a time, later going on to work with Doc Williams and the Coopers. Unfortunately, this band never recorded with Hylo, for the boys also continued to work their factory jobs. As a result, studio musicians were used on his recording sessions which were held during week days. On some sessions an electric guitar, played by Grady Martin, was used instead of a banjo, but even then the musical quality remained high and should be of interest to bluegrass fans. Tommy Jackson and Jackie Phelps also worked on some of Hylo’s earlier sessions on Capitol.

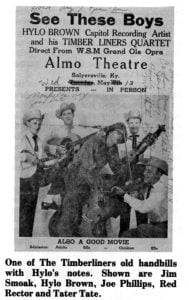

After two and one-half years on the Jamboree, Hylo joined the Flatt and Scruggs troupe as a featured vocalist on both their TV shows and the Grand Ole Opry. With the increasing popularity of this TV show, sponsor Martha White Mills decided to form a second unit to boost their product via live video. Hylo was selected to front this group and his new band, the Timberliners—Red Rector, Tater Tate, Jim Smoak and Joe “Flap Jack” Phillips—have come to be recognized as one of the outstanding bluegrass combinations of all time. At first the band played on a circuit in West Tennessee and Mississippi, and then switched places with the Foggy Mountain Boys and worked through the eastern circuit in a series of Appalachian cities. Jimmy Fox played bass with the group after the departure of “Flap Jack.” Charles Elzie, a fine comedian who was better known as “The Little Darling” or “Kentucky Slim,” joined the group there after having previously worked with Flatt and Scruggs and other groups going back into the early days of radio. The latter circuit was a tough grind but this was a popular area for bluegrass music and the Timberliners usually played to packed houses. In 1959 video tape ended the job with Martha White although TV shows were continued for a time in Parkersburg and Clarksburg, West Virginia.

During this period of the Martha White shows, Hylo and Red Rector introduced the song “Cabin On the Hills,” at WSAZ-TV in Huntington. Flatt and Scruggs’ 1959 recording of it was one of the bluegrass chart makers of the period. Hylo, however, did not get the chance to record the song for himself until he went with Starday in 1961.

In July, 1959, Hylo Brown and the Timberliners became one of the first bluegrass groups to play the Newport Folk Festival. Earl Scruggs worked the festival with them. Three live cuts from their show featuring Earl have been released by Vanguard Records as one of their Newport Festival albums.

The Timberliners with Hylo recorded the legendary album on Capitol of bluegrass and old-time favorites which is often considered one of the most outstanding LP’s ever released. They also did some eight single sides including “Thunder Clouds of Love,” “I’ve Waited as Long as I Can,” and “Your Crazy Heart.” Four of the songs from one session featured the Jordanaires on choral backing which somewhat distracts from Hylo’s excellent lead vocal and the high quality musicianship displayed by Red, Tater, and Jim.

After the breakup of the original Timberliners, Hylo put together a new band with the aid of Melvin Goins who did the bookings. Besides his booking duties, Melvin worked as a featured vocalist and doubled in the comedy role of “Hot Rize Charlie.” This band included Billy Edwards on banjo, Norman Blake on Dobro, Louie Profitt on fiddle and Bill Lowe on bass. Although the TV shows were gone, Hylo’s name was still popular and the group played numerous parks, drive-in theaters and schools in West Virginia, eastern Kentucky and southwestern Virginia drawing good crowds. Together they did Hylo’s last session on Capitol which unfortunately the company has not released. Songs from this session included “Sweethearts or Strangers,” “Dark as a Dungeon,” and a new number entitled “Test of Love,” and a new cut of “Lost to a Stranger.” All but these four of the forty songs Hylo cut for Capitol were released.

In 1961, Hylo’s Capitol contract expired and he began recording for Starday records. Chubby Wise played fiddle on his first album for them and Curtis McPeake, Joe Drumwright, Jackie Phelps, Junior Husky, Josh Graves, Shot Jackson and the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers were among those who worked on his many Starday recordings. On one album, Bluegrass Goes to College, an autoharp was used on some cuts which was played by Rita Faye. This was during the era of the urban folk revival and Starday sought to market bluegrass among the college audience although Hylo himself played only a few campus concerts. He did, however, play a considerable number of matinee shows in high schools in which he performed and commented on a number of folk songs as part of an educational program. While engaged at a coffee house in Connecticut, he went to New York and guested on Oscar Brand’s “World of Folk Music” show for the Social Security Administration. For a brief period in the early sixties he again worked as a featured vocalist with Flatt and Scruggs.

As the urban folk revival began to subside, another financially difficult period hit the bluegrass artist. Hylo, along with other artists criss-crossed into both the bluegrass and country fields in order to survive. He continued to record bluegrass, doing a series of seven albums for Uncle Jim O’Neals’ Rural Rhythm label and a session for Vetco featuring the late Roy Lee Centers on banjo from which only a single has been released. Together with Lowell Varney, Hylo did a gospel album on Newland, each doing half the vocals. At the same time, he did numerous singles on the King’s Music City, Rome, and K-Ark labels with country backing. Hylo did not always carry a band during these years and often played clubs where only a country band was available. Simultaneously, he also continued to play a few bluegrass festival each year. His most recent recording was a bluegrass album for the Jessup people of Jackson, Michigan.

Hylo has also played a number of local jamboree shows in recent years. Among these are the two Pike County Jamborees in Ohio and Kentucky. At the Piketon, Ohio show, Hylo played frequently with Roy Ross and his Blue Ridge Mountain Boys, a good local bluegrass band that also recorded an album on Rural Rhythm of their own as well as backing Hylo on three of his albums for Uncle Jim O’Neal. The activities of the Blue Ridge Mountain Boys in recent times have been curtailed by leader Ross’ election as Pike County sheriff in November, 1968, and subsequent service. At the Belfrey, Kentucky show where Hylo has guested frequently over the years, he was commissioned a Kentucky Colonel by Governor Louis B. Nunn. Jamboree emcee, Sam King, presented Hylo his commission in March, 1971.

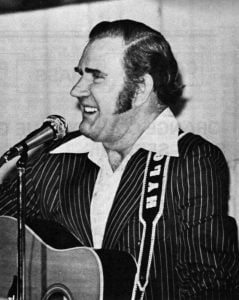

Recently, Hylo left Nashville and has obtained a farm near Jackson, Ohio. He is continuing to play clubs as well as parks, theaters and occasional festivals during the summer months. Hylo also works some high school matinees in Eastern Kentucky giving folk song programs. He is working at assembling some new bluegrass material and musicians; and should be recording again soon. Hopefully, these new recordings will approach the level of his earlier work for Capitol and Starday. For many artists their early recordings are those most highly praised and sought after by collectors. This has been especially true of Hylo Brown. His earliest efforts were so good that it has been a constant challenge for him to equal the excellent quality of this work of the middle and late fifties. The potential is there—let us as bluegrass fans look for it to again be achieved.

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

I played for hylo for a while he was something else, a good ol guy in a lot of ways talented, we stayed a lot at the highland inn in paintsville ky we always met Steve Goodman there to share stories and new songs Steve had written, thats about the time city of new Orleans was coming on, i think willy did a cut on it. Had a lot of fun,,,and some rough times.