Home > Articles > The Archives > Bobby Osborne – On His Own

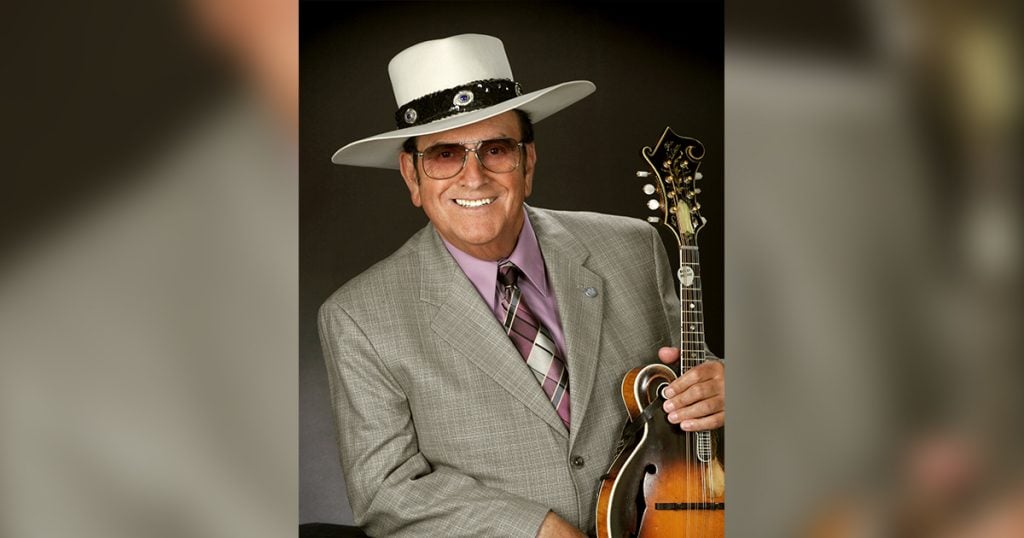

Bobby Osborne – On His Own

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

September 2006, Volume 41, Number 3

Bluegrass music legend Bobby Osborne could care less if he ever boards another plane, but he is willing to fly solo with his career. One of the industry’s most talented vocalists had the choice of staying grounded when his partner of more than half a century, Sonny Osborne, decided to retire in 2004.

“When my brother decided to quit the road and completely retire, the days of the Osborne Brothers were over.” Bobby said. “I couldn’t see any point in me trying to just keep the Osborne Brothers as just one brother.” Left with the choice to step down from the business or venture out on his own, the elder brother, 74, didn’t hesitate on his future. “I’m not going to [retire] myself. I’m going to go on as long as I can. I feel like I was put here to sing, and that’s what I’m going to do.”

Determined to prevail as a solo act, Bobby still had a high degree of trepidation before he stepped out on stage that first time without his longtime partner. “I was worried about getting in front of an audience.” Osborne candidly admits. He was concerned with the public’s perception. “You did okay with your brother. Let’s see what you can do by yourself now.”

“I thought of the Louvin Brothers when Ira passed away. Charlie told me one time. ‘You stand with your brother beside you for years and years and you look over there, and he’s not there. You feel lost out there.’ Sonny and I were together 51 years. You can’t get over 51 years of anything I don’t guess. It was pretty tough. It’s just like anything else. If you’re relying on somebody else to help you load a wagon up and all of a sudden, you’ve got to load it yourself, it’s different.”

His burden was made a little easier by his band, the Rocky Top X-Press. which includes Daryl Mosley (bass and vocals), Dana Cupp (banjo and vocals). Matt DeSpain (resonator guitar and vocals), and the record debut of Osborne’s youngest son, Bobby Osborne. Jr., 17, (rhythm guitar).

Though Bobby was tethered to the Osborne Brothers’ history, he was happy to have the freedom to write a different chapter for his musical future. “I hated to wait this long or get this old. I wish I could have done it a long time ago. I always figured Sonny and me together had something special and separate we didn’t have anything, which that was probably a bad way to look at it. I knew together we had a winning combination.”

During the years that the Osborne Brothers were with Decca Records Bobby said he had more of a leadership role with the band. But he says when they parted ways with the label, Sonny took over the reins. “He wanted to get into producing. He got to the point where he wanted to just kind of be a leader, and I just let him go ahead and do that. I kind of laid back and did what I knew how to do. When this came along here, I knew I had to put myself out there as a leader and be able to take on that responsibility. There comes a time when you have to stand on your own two feet, and this was the time for me.

“It was a little bit different. Although probably some people thought that I would have trouble doing that. I’ve had no trouble doing that at all. I try to treat people just exactly the way I want them to treat me, and it’s worked out the best for me. I’m really enjoying it. It’s a brand new career for me.”

With a different direction to his life, in 2005, Osborne inked a label deal with Rounder Records. He co-produced the CD, “Try A Little Kindness,” with Glen Duncan, famed sessions fiddler and Osborne’s own choice to be behind the control knobs. “Glen is a great talent. I wanted to do the best with it because it was the first bluegrass CD that I had ever done by myself. I think I might have overdone it a little bit. It really turned out good. I was tickled to death the way my voice came out.”

Through instrumentation, musical arrangements, and song selection, Osborne and Duncan attempted to weave together a fabric of sound that was unique to the talented high-lead vocalist. “Of course, when I open my mouth, people are going to think of the Osborne Brothers right then and there. But I wanted the sound of Bobby Osborne to be as different to people as the Osborne Brothers was.”

Osborne also had the help of one of Rounder Records founders, Ken Irwin. While Irwin is not a musician or singer himself, Osborne was surprised at what skill his label boss brought to the recording sessions. “Ken is a guy that hears things like the first word of a line. A lot of people will let up on the first word or the last word of a line and they don’t sing it as loud as they do in the middle of the sentence. He hears little nuances like that, and that helped to make it a great CD.”

His 12-cut solo project includes Bobby’s creative spin on some of the classic bluegrass recordings. “I guess it’s just natural that people would want to do a Stanley Brothers song or a Bill Monroe song. They’d want to sing it like them, but I never did see it that way. There was no point of anybody else trying to do better than Carter and Ralph Stanley and Pee Wee Lambert on “The Fields Have Turned Brown” because you couldn’t do it. So, I chose to do it my way. People can’t call me a copycat that way,” Bobby laughs.

Osborne had performed the song more than half a century earlier when he had a brief stint on stage with the Stanley Brothers. “I sang it some with them in Pee Wee Lambert’s place, but I always liked the song. I thought one of these days I’d love to record that. I never dreamed at any time that I’d ever talk anybody into letting me sing “The Fields Have Turned Brown.”

The elder bluegrass music statesmen also turned his ear to another genre for one song choice. He was watching an NBA game one night when he heard part of pop icon Paul Simon’s “Fathers And Daughters” playing in the background of a commercial. “It reminded me of some songs like “Roll Muddy River” and “Rocky Top.” The Wilburn Brothers put out “Roll Muddy River.” They played it real slow and sang it fast. When we recorded, we just did it the opposite. We played it fast and sang it slow. “Rocky Top” was the same way. When we heard “Rocky Top,” Boudleaux Bryant was singing it fast and playing it real slow. Those two worked out great. I got to thinking about “Fathers And Daughters” on that same idea. We got it up tempo and I just sang natural, just like Paul Simon did it. Everything just fit right into place.”

Bobby offered up a sample of six of the CD’s recordings during a tribute concert in his honor on March 24, 2006. “I didn’t think anything like that would ever happen to me. I thought, ‘Man, nobody is going to come out and see me do anything in Nashville except perform at the Opry. They come to see the Opry and not one certain person.’” On hand to pay their respects were Larry Stephenson, Claire Lynch, the Grascals, Marty Stuart and his Fabulous Superlatives, Alecia Nugent, and Marty Raybon. The event was held at the Belcourt Theater, the former home of the Grand Ole Opry from 1934- 1936.

“It was really over and done with before I realized what had happened. I was real nervous. I was really pleased to have a tribute done for me. In another way, I got a good night’s sleep when I went home. I wasn’t nervous after I got it over with,” he laughs.

In paying homage to Bobby, many of the artists acknowledged the immense influence the Osborne Brothers had on them personally and on the genre as bluegrass innovators. Modestly, Bobby admits little understanding of the brothers’ impact on the profession.

“I don’t think we either one realized the impact that we had on the bluegrass world or country music while we were out there on the road. I think I’m realizing that more now than when Sonny and I were together. While you’re creating that legacy, you’re just adding to the flame.”

Born in Hyden, Ky., and raised in Dayton, Ohio, Bobby grew up tuning into the WSM’s Grand Ole Opry Saturday nights on his dad’s old stand-up battery- powered radio. He was enchanted by Ernest Tubb’s voice. “At that time, my voice was kind of low, and I got to learning his songs and singing them. I loved the way he sang. He’s the first guy I’d ever seen on stage from the Opry. While I was listening to him, I was just a little ol’ boy trying to learn how to play. I thought, ‘That’s what I’d like to do right there.’ I never thought about it ever happening. I followed him and followed him until one night I was listening to the Opry, and I heard Earl Scruggs play ‘Cumberland Gap’ on the banjo. Boy, I never heard anything like that coming out of a radio in my life!”

At the time, Scmggs was a member of Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys. When Osborne heard they were coming to town, he got a ticket for a seat ten rows back at Memorial Hall. “I can’t believe that one guy does that with a banjo. I told my dad, ‘I’ve got to go see that for myself.’ In about a minute and a half, Earl Scruggs showed me. I just fell in love with bluegrass.

“Then, I got to following Bill Monroe and Flatt & Scruggs and Chubby Wise and Cedric Rainwater. Every time they played or breathed, I did too.”

As a young musician, Bobby had his sights set on learning the guitar. But when Jimmy Martin joined him and the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers in 1949 in Bluefield, W.Va., his playing took a different path. “[Jimmy] said, ‘I’m going to play the guitar. You’ve got to play the mandolin.’ I said, ‘Well, I’ve got one here,’” (Bobby had recently plopped down $15 for an old mandolin while visiting in North Carolina.) He said, ‘Well you might as well learn how to play it because the tenor singer has got to play the mandolin,’” Osborne recalls with laughter. “I got to like that mandolin. Of course, that’s what I stuck with all through these years. Nobody knows me as a guitar player.”

The world-renowned tenor and mandolin stylist eventually teamed with his brother after serving a stint with the Marines during the Korean War. They experimented with instrumentation by incorporating drums, piano, pedal steel, and other electric instruments into bluegrass music. The brothers scored with hits in both the country and bluegrass fields with songs like “Once More,” “Rocky Top,” “Ruby,” “Georgia Pineywoods,” “Midnight Flyer,” “Tennessee Hound Dog,” and “Up This Hill And Down.”

“We just did it all and went everywhere you can imagine to take bluegrass. We had a lot of firsts to our credit. I just felt like he and I took the bluegrass to places where it might have never gone.”

Now Bobby wants to reinvent himself and make an impact in the genre on his own. “I’m looking to do things that I never did do before and sing to people and make friends and fans that accept me as a solo act. I don’t know how many years I’ve got left, but I’m really enjoying what I’m doing. I feel like I’ve got some more things that I need to accomplish. I’ve already proved one point. I want to prove another one.”

The Osborne Brothers Legacy

The Osborne Brothers were true innovators in the field of bluegrass music. They introduced fans to the high lead vocal trio harmony on record and made bold creative moves by sampling with drums and electric instruments in their songs. The brothers’ forward-thinking approach garnered them admirers in both country and bluegrass music circles and took them on a path to stardom that lasted more than half a century. Along the path of success, they tallied a number of firsts for their profession, including the first act to win the Country Music Association’s Vocal Group Of The Year Award in 1971, the first bluegrass group to perform for the President, and the first bluegrass band to entertain on a college campus. Their accolades climaxed in 1994 when the Osborne Brothers were inducted into the International Bluegrass Music Association’s Hall Of Honor.

Although the siblings brought their astounding career to an end when Sonny retired, they left behind landmark achievements. Brother Bobby continues on as a solo act and recalls some cherished memories.

On the extreme success of “Rocky’ Top, ” and the song’s origin.

I think it’s just as popular, if not more so now, than it ever was. Last time I checked Billboard magazine, it was still listed on the charts. When we got to do the song, we were looking for one song to finish out the session of recording. We had recorded some of Boudleaux [Bryant’s] songs prior to going with the Wilburn Brothers. But we were with Acuff Rose [publishing company]. Sonny called Boudleaux up and asked him if he had anything that we could listen to. He said, “I’ve got one song— it’s not finished yet. You can come listen to it.” Sonny goes over there, and he immediately calls me. ‘Come over and listen to this song. It may be something we can do.’ I go over there, and he was just singing it real slow. That thought came to my mind like we did “Roll Muddy River,” and I thought we could do that. He finished it that afternoon, and we took it the next day and recorded it.

The Osborne Brothers have the distinction of claiming not one, but two official state songs from their catalogue— “Kentucky ” for the bluegrass state and “Rocky Top’’ for Tennessee, which is also the anthem of its University of Tennessee football team. Standing on the fifty’-yard line to perform the tune with U. T. ’s Pride Of The Southland Marching Band revved up the brothers adrenaline and pumped up over 97,000 raging Big Orange fans.

Man, what a day that was! No use of turning your back around to the other side [of the stadium] because there’s just as many fans on that side you know. It’s awesome. We’d say “Rocky Top” and hear it two blocks away coming back to us. We just had to kind of listen to them [the band]. It was a great day.

On being the first bluegrass band to play on a college campus. (Antioch College, Ohio, 1959)

I thought, “Man, I don’t have any business in a college. I never went through high school, let alone going in a front door of a college.” We thought in a college they’re probably from the city, and they want to hear the newest country songs. We got to doing some of them, just country songs. Everybody just sat there. I thought I’ll be glad to get out of here. We took a little intermission, and this boy [the event organizer] came back there.

“Don’t you know ‘Pretty Polly’ and ‘Little Maggie’ and some of them of bluegrass songs?”

“Yeah! We know plenty of them.”

He said, “That’s what they want to hear.”

We said, “They couldn’t.”

“Do one of them and you’ll see.”

We went out there and did this old song called “Little Maggie.” Daggone place went up in smoke! “Gosh, we’ve got it made here man.” We started singing all the older songs like “Pretty Polly” and “Man Of Constant Sorrow,” and them people just absolutely went completely crazy. We could hardly get off the stage when we decided to leave. He said, “Didn’t I tell you!”

On taking bluegrass music overseas.

They treated us in Japan like they treated Elvis Presley in this country here—really scary. We went to Japan and this auditorium we played in Tokyo seated 1,800 people. The guy that booked us over there said, “When you get finished, take two or three pens with you because you’ll be busy signing some autographs.” I shook hands with 1,800 people and signed my name 1,800 times. We stood there until the last one of them left, and they weren’t going to leave until they got our signature. It beat anything I’d ever seen.

The Osborne Brothers also traveled to Germany as part of a 12-city package show. At first, they opened for country legend Faron Young, but the crowds went wild for the brothers.

We were only allowed to do twenty minutes because it was such a big show. Faron, of course, was in the Army and stationed over there somewhere in Germany. He thought he could go back and just have a big time. We did three or four songs and Sonny—before we would do “Take Me Home Country Roads”—would always play an instrumental. This big roar got to going on back through [the crowd]. I didn’t know what it was. By the time we started into “Country Roads” we could hardly hear how to sing the song. We thought we were doing something wrong. They were going to throw us out of the country or something. But that happened about three nights in a row. After that, Faron Young went to the guy and he said, “Look, I’ll just go on now. You put me on before that.” The guy said, “I can’t put up with that. Let them do it. It’s their show man.” That was the wildest thing. Everybody that plays should have that happen to them one time in a lifetime.

On being the first bluegrass act to play for a U.S. President (Richard Nixon).

We were on a tour with Merle [Haggard]. They wanted us to come to the White House and play on that Saturday for Mrs. Nixon’s birthday, which was on Monday (St. Patrick’s Day). They wanted a Merle Haggard show (and that included us) to come to the White House. I didn’t think much about it. We were just going to do four songs. The Senators and Congressman and their wives from all fifty states attended. They were just packed and jammed in that little room. I’m looking out through yonder. He [President Nixon] was watching Sonny’s fingers. I saw him watching and I thought, ‘Man, alive. ’ I got to thinking where I was at— standing in the East room, singing for the President of the United States. Gosh! That was scary. Not only did we get scared that night. He [Haggard] got scared and dropped his guitar pick. He did that song “Walking On The Fighting Side Of Me.” He had it backwards. He said: You’re fighting on the walking side of me.

After the President went to bed—or “retired for the night” is what they said up there—all these Senators and their wives went into this huge room. It really shocked me to learn the amount of Senators and people running our country had banjos and fiddles and mandolins at the house trying to learn how to play. They’d come up to you and say, “I’ve got one that looks just like that right there at the house.” And I said, “Do you play it?” “Oh, yeah. We fool around with it some.” It just amazed me the ones that had those bluegrass instruments at their house.