Home > Articles > Learn To Play > Making Friends With Music, Making Music With Friends

Making Friends With Music, Making Music With Friends

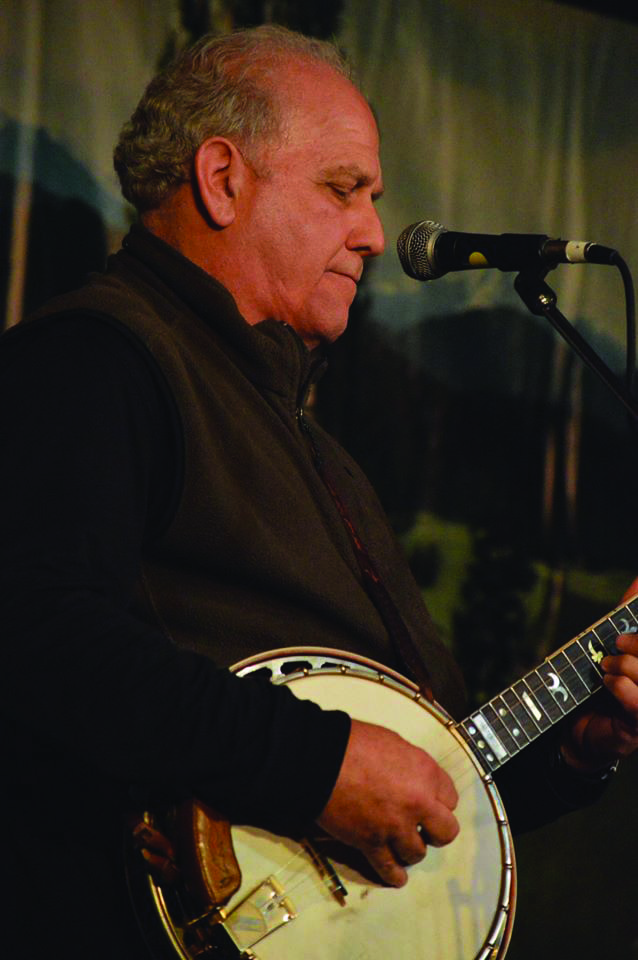

It’s hard to imagine a bluegrass fan who has never heard of Pete “Dr. Banjo” Wernick. After all, he’s well known as the banjo player for longtime fan favorites Hot Rize. His 1974 instructional book, Bluegrass Banjo, has sold roughly a quarter-million (!) copies. He was the first president of the International Bluegrass Music Association (IBMA). His hard-hitting song “Just Like You” has become something of a classic. And those are just a few career highlights.

But if you’re new to bluegrass, you might associate Pete’s name with the Wernick Method, his carefully thought-out approach for teaching jamming skills to amateur pickers, used by an international network of instructors. The fruit of decades of insight, experimentation, and evolution, the Wernick Method has roots that go back to Pete’s teenage years in New York City.

Pete began teaching banjo while studying sociology at Columbia University in the 1960s. Early on, he encountered students who learned the arrangements he showed them, but couldn’t see their way to playing anything else. So he started teaching them as he himself had learned: by following the chords to simple songs, focusing on backup before introducing lead arrangements. This approach informs the early chapters of Bluegrass Banjo, and Pete carried it over into the banjo camps he started offering in the 1980s.

Then in 1996, some banjo camp students asked whether he’d consider devoting an entire camp to jamming. “I said, ‘Well, I’d need to bring in some guitar, mandolin, bass, and fiddle players,’” Pete recalls with a laugh. “We got a crowd of people, but none of them really knew much about jamming. I faked my way through it, and we had some success. Much to my surprise, when I ran another class I got a whole ’nother bunch of people.” He had stumbled onto an untapped market whose size would surprise him.

In 1999, Pete converted his annual MerleFest banjo camp into an all-instruments jamming camp. Around that same time he presented his ideas to a room full of music teachers at the IBMA business conference. At the heart of his approach is a simple insight: Most people who take up bluegrass instruments aspire to play socially with friends. But bluegrass instruction has mainly focused on tunes and breaks, not jamming skills. Too often students get to the point of playing a few complex pieces slowly and haltingly, but have no idea how to interact musically with others. They feel they’ve failed, and that they’re the problem. Discouraged, they stop playing, and instruments gather dust under beds or in closets.

The key, Pete realized, is the social component. Even the simplest playing can be fun and fulfilling when it’s part of a rewarding social interaction. Once pickers get a taste of that, they’re hooked. They want to keep playing and to improve their skills. They continue taking lessons, trade up to better instruments, attend festivals. The entire bluegrass community benefits: teachers, music stores, luthiers, promoters, musicians. But that all begins with getting amateurs jamming—and Pete’s student surveys bear this out.

So Pete analyzed jamming into small, teachable skills. On the most basic level, to play with others you need to stay in rhythm and follow the chord changes. This can be done at slow tempos with a simple guitar strum, mandolin or fiddle chop, or banjo roll. Sing a melody on top of that, and you’re making music; you don’t even need instrumental solos. The results may be a far cry from Flatt & Scruggs or Alison Krauss, but for students who have only played by themselves the experience is a revelation, and serves as a foundation for building higher-level skills.

Pete’s method focuses on songs, not instrumentals. Playing a fiddle or banjo tune acceptably is daunting for novices, but many favorite songs have simpler structures and shorter solos. Beginners on different instruments often learn different tunes. And while instrumentals may have quick chord changes or unique progressions, most songs have predictable progressions that they share with other songs. In short, instrumentals are generally harder for jammers to follow and fake than songs.

Once the foundation is laid down, students learn techniques for memorizing chord progressions on the fly and insight into jam etiquette and song structure (verses, choruses, breaks) so they’ll know what to expect next while playing. They’re given instruction on faking solos, starting with rudimentary “placeholder solos” (picking or bowing any notes within the chord), moving up to “filler content solos” (using standard licks without attempting to play a melody), and eventually melody-based solos. Singers get tips on choosing comfortable keys, and an introduction to harmony singing (just a taste, but enough to demystify the topic). More experienced students are given extra challenges suited to their skill level.

For part of every session the students are divided into small groups to practice their new skills. They take turns leading songs—deciding on the key, singing lead, and signaling who takes the next break and how and when the song will end. This doesn’t always work out perfectly; mistakes are an expected part of the learning process. But a coach is always present to help students figure out what went wrong, and to offer praise and encouragement when things go right.

As Pete sees it, it’s essential to keep these groups small so students experience what makes bluegrass dynamic and interactive. Thinking about the massive clusterplucks often found in open jams, he opines, “That’s not bluegrass! It’s like bluegrass, but what if 20 people wanted to play basketball, and they all got out on the court? It would not be the game of basketball!”

For roughly a decade, Pete offered jam classes and camps near his Boulder, Colorado, home and at various major festivals. But a turning point came in 2009. That May I was preparing to drive up to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, to assist Pete and his wife Joan, as I had done for several years at their camps at the Gettysburg and Grey Fox festivals. But with only a week to go, Pete called to say Joan had been hospitalized with a mysterious illness. Rather than cancel the camp, he asked me to run it in his place. He hurriedly wrote up his procedures, and armed with his notes I managed to get the job done. I felt like a jammer who finally leads a song after years of following along by watching the guitarist’s left hand and faking solos.

It was the first time Pete had instructed another teacher to use his methods. Joan recovered, and Pete started thinking in earnest about expanding his operation beyond what he himself had time to teach. He turned to Rick Saenz, an information technology professional who had attended his MerleFest camp several times. Together they devised a system. A central office handles registrations, advertising, and geographically targeted promotional emails; sends orientation materials to students before each class; and tabulates students’ evaluations once a class is completed. Instructors also publicize classes on their own mailing lists and social media. While they must agree to follow Wernick Method procedures, they have wide leeway in deciding on a class’s size, location, schedule, format (weekly classes, multi-day “camps,” or single-session festival classes), and price, 15% of which goes to the Wernick Method office. Since 2019 the office has been run by Leslie Dare, a North Carolina-based Wernick Method instructor (and former student).

To help Pete and Rick test their computer system and office procedures, I taught a class in the fall of 2010 at the home of one of my banjo students in Potomac, Maryland. The class took place over four successive Sunday afternoons and drew 14 students. It was a success. One student who had been discouraged by open jams he’d attended commented, “I come away [from the class] feeling positive about myself and motivated to continue.” My assistant, singer-guitarist Lynn Healey, told me, “I was amazed at the students’ obvious and significant progress.”

Since that first class, Pete has certified 150 instructors to use his methods. As of December 2020 there had been 943 Wernick Method classes and camps in 46 U.S. states, as well as Australia, Canada, the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Mexico, Slovakia, Spain, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. The Wernick Method has tallied over 10,000 student registrations. Wernick Method teachers have collectively earned for themselves a total of over $1 million teaching jam classes.

The best-known Wernick Method teachers are Wayne and Kristin Scott Benson, who’ve taught camps in South Carolina when not on the road with IIIrd Tyme Out and the Grascals. Other prominent musicians on the roster are Bob Amos, Chris Brashear, Ellen Carlson, KC Groves, Jimmy Heffernan, Don Julin, Barry Mitterhoff, Liam Purcell, and Dan Whitener. Gilles Rézard and Petr Brandejs may be less familiar to Americans, but they’re well known to pickers in France and the Czech Republic, respectively.

Gilbert Nelson of Spartanburg, South Carolina, is the most enterprising Wernick Method instructor. Since 2011 he and his wife, Leigh, have run more than 120 classes and camps ranging in attendance from just five to more than 40 students. They’ve “graduated” more than 1,500 students.

With Pete’s blessing, Gilbert has experimented with different instructional formats. “The Wernick Method is always on display,” he explains, “even while the actual expression of it can take different forms—steering away from a rigid syllabus style approach, digging instead into topics that arise as we play.” Among his enhancements are instrument-specific “breakout sessions” and a nonstop “eternal jam” for more experienced students.

Instructors welcome the opportunity to earn income in their off-seasons, or on underutilized days of the week. Often students end up taking private lessons from their instructors. But the rewards are more than monetary. Kristin Scott Benson notes with satisfaction how timid students blossom in the “safe place” that Wernick Method classes provide. “They’re not the intimidating free-for-alls that force many people into their musical shells. They’re invitations to crawl out.” In that environment, she observes, “People become friends and stay connected. You can see relationships develop that continue well beyond the weekend.”

Countless students have experienced this mix of musical progress and we’re-all-in-this-together camaraderie. For longtime classical musicians but bluegrass newcomers Alice and Dan LaRusso, their DC-area classes were an introduction to a whole different approach to making music. “When I started playing guitar five years ago,” Alice recalls, “bluegrass was completely foreign to me. Soloing on the fly, figuring out chords, singing tenor were mind boggling to me—someone who had always relied on reading sheet music and following conductors.” After their classes ended, they began hosting regular jam sessions with the friends they’d made. They even formed a group to play at church and community events.

Jana Pfeiffer “had no idea what was going to happen” when she first brought her banjo to Scott Wilkins’ Wernick Method class in Lanesborough, Massachusetts, yet she felt “sure that I would not be able to do it.” Like the LaRussos, she learned that jamming is as much about fellowship as it is about music: “This group made me feel welcomed and included. It got me going to festivals and I met these wonderful people and now play with them regularly.”

The COVID-19 pandemic put everything on pause in March 2020. But once the virus and its transmission were better understood, Pete established protocols for instructors to follow, with sanitizing, ventilation, masks, and smaller classes—outdoors when possible—to allow for distancing. Vocalists can use microphones and small amplifiers to avoid the kind of vigorous singing that has been implicated in some “superspreader” events.

So despite fewer and smaller classes, the Wernick Method has carried on in these extraordinary times. As restrictions start to lift, Pete and his teachers are now scheduling classes for late spring and summer. They know bluegrassers everywhere will be itching to jam again, and the Wernick Method will be there to make sure that no picker is left behind.