Home > Articles > The Archives > Kenny Baker

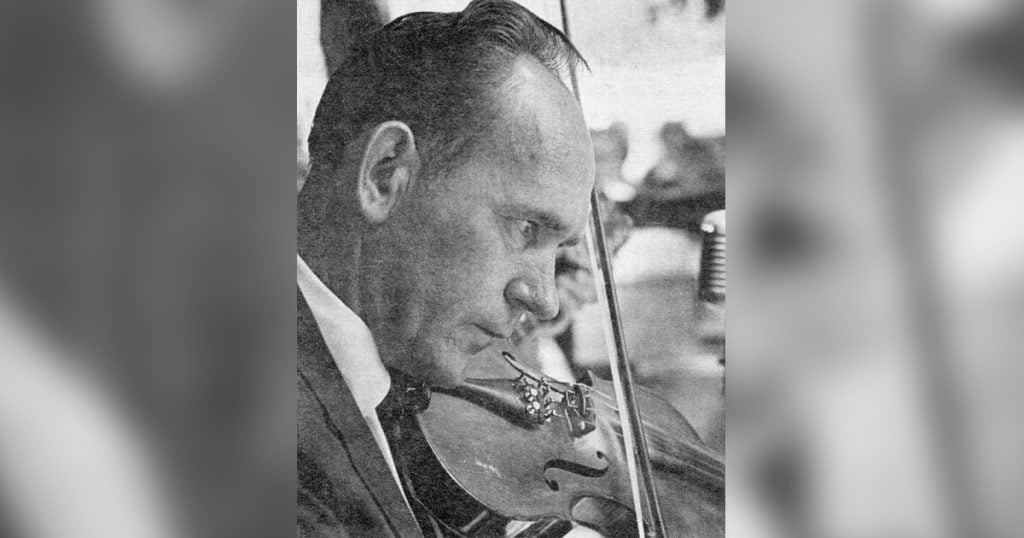

Kenny Baker

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

December, 1968. Volume 3, Number 6

Kenny Baker plays fiddle with Bill Monroe. He was a coal miner, a Country & Western fiddle man, and is a very articulate’ person with a lot to say.

From Jenkins, Kentucky, he was born June 26, 1926. His family originally came from England and settled in North Carolina. “As a matter of fact this great ancestor of mine slipped out of England… I think that knowing my people… they were fortune hunters maybe, or… you might say they were more or less explorers. They definitely didn’t stay in one place too long. My mother’s people as near as I can get back to come from maybe a Dutch descent… My great grandfather settled in Wise County, Virginia… I was raised in Wise County to a great extent. I used to stay with my grandparents quite a bit… the only reason in the world why Jenkins is my home is because that’s the only public work they had there and my daddy bein’ a miner, why that was it.”

Jenkins was set up as a coal town by Consolidation Coal Company. They sold out to Bethlehem Steel somewhere along in the early fifties. “Now there’s some wild stories can be told about the [union] organization… The coal companies didn’t recognize no union laborers at all… they bought the property, built the houses, rented you the house and any time they caught more than two or three men together they broke it up – they had these company police to come around and just break it up…they had to meet back in the mountains, and they just stole out here and there to meet and plan their labor moves… my father was very active in that.”

Kenny started trying to play the fiddle when he was eight or ten years old by imitating the first person he heard play—his father. “Daddy played such stuff as ‘Billy In the Low Ground’, ‘8th of January1, ‘Forked Deer’… all old-timey tunes you know. I can remember hearing my great-grandfather, Richard Baker, play. He was 96 when he died.” But Kenny gradually became discouraged. “… I just give the fiddle up… my dad kind of criticized me… he said I’d never learn… well really and truly, he tried to teach me and… maybe I just didn’t have enough interest or whatever it might be… and he just made a rulin’ for me not to get that fiddle… and from there on every time I got in there I stole it…”

He mostly played guitar until he was sixteen when he went into the Navy. The first time he played the fiddle more or less formally was for a USO show on a dare.”… they just wanted to see if I really had the nerve I guess, and so – you know me – I just walked right up there.” Later, when the Red Cross put on a square dance and didn’t have a fiddler, Kenny volunteered because he knew some square dance tunes. They flew a fiddle into the base and he worked on it to make it playable. “That’s the last guitar work I did then.”

Back in Jenkins after his discharge he went to work in the mines as a coal loader – “… 130 pound a day, man… averagin’ about 8 dollars a day…” – and didn’t play fiddle for three or four years. He started up again by playing for local square dances with two other men, Virgil Mullins and Glenn (Slick) Gallion.” The same thing happened twice… they needed somebody to play the fiddle.” He played locally for two or three years in addition to mine work. “… very rarely we would do some work [playing] for the local coal company there, if they had some kind of a big day… such as safety days… labor day celebrations…”

“The biggest influence I ever had with the fiddle was Marion Samner. Marion was a more up to date fiddle man than my father was… he started me wantin’ to learn to play a fiddle… he was from Hazard.”

Kenny’s first real interest was more in jazz fiddle and he listened to guitarist Django Reinhardt and fiddler Stephane Grappelli, noted French jazz musicians. “The first fiddle playing that I studied at all… or even thought about was of that nature [jazz]… I took numbers like ‘Darkness On The Delta’… from the Ink Spots… the Mills Brothers used to do that number… and I’d just play ’em the way I wanted to play… of course down in the country when I played that stuff I had to play it to myself… It was a new sound and I liked it… just like eatin’ a piece of bread at your mother’s house… I was a great fan of Tommy Dorsey’s and Glenn Miller particularly… he used to hit licks… I’d take my guitar – along at that time you know I didn’t study what the guitar player was playin’ – it was the licks he [Glenn] had… I used to listen to a lot of orchestras… you get your own ideas from stuff like that… You take this ‘Careless Love’ thing that Bill recorded… the idea of the tune come to me in a movie… I think it was… Nat King Cole… and he did this number. He did it real slow and it was the first time I ever heard the real chords… it’s the first time I ever heard the real down meanin’ of that tune and the melody, see – the lyrics – today I couldn’t even think about them -but it was the music that he was gettin’… and after I heard Bill sing – I didn’t even know Monroe at the time I saw this movie – … we was in this recording session one day and we was beatin’ around tryin’ to hunt another number and I happened to think about that number… I thought, ‘well if I show it to him just exactly like he done it, he’ll not be interested but if I’boost it up just a little bit he might’… so we tried it and we took one cut and right there and then we just recorded it… every note I hit, this man had it on the piano.”

“I wasn’t interested in the big band sound, but I liked the way they [the soloists] went about it… their notes are more distinct. Now that’s gettin’ back to this Grappelli and the difference in him and my daddy’s playin’ you know… Now the difference that I made in the music, Grappelli played his music with a distinct sound and every note was there… every note he played meant something – he’s not a mechanical fiddler. Now every day you hear somebody play tunes like ‘Soldiers Joy’ and this and that and nine old-timers out of ten when you hear one man play it you’ve heard ’em all… Some might be a little smoother, but they all stick to the same notes, they never give or take…”

About 1953 Kenny and a band went to WNOX in Knoxville to play the Saturday Night Barn Dance. Lowell Blanchard offered him a job but he turned it down because right then he didn’t feel like playing music for a living. About a week later Don Gibson called him. “… just as things happened in the coalfields… they had made a new machine which took the place of about eight men on one section… a lot of people felt bitter about it… if you figure from both sides, the labor and the operator, why I think they were in their rights… they were in there to make the money… I was put off on Wednesday and Don called me on Thursday… so I said I’d try it with him.”

Kenny says he learned a lot about playing a fiddle from being with Don Gibson. “… I learned to pick up notes that would sound to me like they would be a major maybe, and a minor, and I learned to pick up a lot of rhythm licks, you know, that I had never even dreamed existed… a very good teacher… He don’t play, but he’s got enough know-how about him to where he can put his finger right on what he wants.”

Kenny hadn’t had much of any chance to play jazz fiddle until he went with Don Gibson. “… When I got with him I found that the steel man that he had, and himself too, they were deeply interested in that stuff… we just kind of worked it all over.” The new musical ideas that he developed “came from banjo pickers and maybe a few licks I heard on a horn here and there – and this and that. It’s just ideas that you drum up you know. Of course there’s no use in me a-sayin’ that I didn’t listen to no fiddle players… about the only listenin’ I ever did really, was to learn the melody but as far as takin’ a recording… and just study it note for note, I never do that.”

He worked with Don for about four years. Then toward the end of 1956 Kenny went with Bill Monroe. Bill had originally heard Kenny in Knoxville and had spoken to him two or three times about working with him. “There wasn’t no particular agreement really, he just asked me a couple of times and at the time I decided to go I felt I needed to go so I went … When I went to work for Bill, the change I had to make in the music … you might say it was a big challenge … I decided before I ever went there I just knew I could play that kind of music without even thinking about it. I found that I didn’t know near what I thought I did. Bill explained to me after I’d worked with him for a while that he felt that my fiddle would help his music some …I was trying to make myself believe that I couldn’t play what he wanted and at that time what I thought he was wanting, I just couldn’t put it in there, you see.” At the time a friend of Kenny’s was helping him learn some of the breaks and tunes. “The meter and the notes he was giving me to play, I just couldn’t put ’em in there … I explained to Bill that I couldn’t put the stuff in there … he said, ‘now don’t listen to what somebody else is playing, you play what you feel and what you hear, that’s why I want you'”.

“I found Bill very easy to work with in recording … he sets his music up and he tells you what he wants … he either let me get away with a lot or else we heard the same stuff … we would take a number and if it was a strange number to us they’d play it for us … and we would listen to it and each man would figure out his break … and then we would start with it and somewhere along the line some man’s gonna make a boo boo then that gives you another chance to improvise this number as you go with it … four times most of the time we generally had a pretty good cut.”

Kenny left Bill in 1958 or 59, returned after a short while, left a second time, went back again and stayed until 1963 when he left and went back to Jenkins to work in the mines. “I’ve got to refer to Bethlehem Steel … that company is not a cutthroat outfit … they’re deeply interested in your family … if a kid cranes up and they see that he’s got a pretty good head on him that company’ll willfully send him to school … they’re far ahead of the first company that was there … I went to school in the Safety Department for Bethlehem Steel … a program they had to eliminate accidents in the mines … You go around and you check each and every machine that they had and make sure it was permissible …”

Kenny stayed with mine work until 1968 when he went back with Bill. I was interested in some of his thoughts on the area of Eastern Kentucky—Kenny is a friend of Harry Caudill, author of the book Night Cranes to the Cumberlands, and he is very aware and interested in the problems of that section of Appalachia.

“… and no man after he gets up to the age of maybe 40 or 50 years old and if he’s dedicated his life in the mines and once he leaves there regardless of what kind of job he gets he’ll never be satisfied away from the coal mines … you spend more time underground than you do outside … you learn to live with very abnormal conditions … once you get away from it, it kind of bugs you just a little bit—I’ve had some of that, I know … that’s home to them … and the mining part of it is just as much as bein’ in their front room …”

“Well here’s the thing now. If they’re so interested in the welfare of the poor people down there, why do they go down there and appropriate a lot of money and send it in there to a bunch of political leaders and the money never even got to the people that they need … as a matter of fact there’s six men on trial now in Eastern Kentucky on that … $75,000 I believe was the government grant to them for that one particular county … they could only account for maybe ten or fifteen thousand dollars … even the county judge was in on it, and the D.A. … so I hope they get their money’s worth out of it.”

While Kenny was in Washington recently, he listened to a tape of a Bill Monroe show made in 1957 at New River Ranch in Maryland. “I’m real proud that show was taped … I’ve often studied what I did sound like back in them days… you could tell… I wasn’t no grass fiddle man in them days, you can tell it … real pitiful … I was searchin’ that fiddle for the sound I was wantin1, that’s exactly what it was … It was disappointing I’ll tell you, but I could also hear some stuff in there that I was hearin’ in them days that … I can put it in there today … I was tryin’ and I was searching … I could hear it but I just didn’t have the ability to put it to it … if you’ll notice there was very few fiddle take-offs that we had there … but that just goes to show you now—I really thought I was pulling the wool over Mon’s eyes there … I believe he thought, ‘well how long is he gonna take him to get away from that other stuff he’s been playing’, I guess that entered his mind—or else, ‘you reckon he’s lost his mind or what?'”

“… let’s say that Bill has, whether he knows it or not … farly advanced his music …

I think he’s been very creative in the Nashville sound … he’s the first man that ever used two fiddles down there … and of course Pee Wee King and Redd Stewart and those boys they were there years ago … in western swing music two fiddles has been a pattern all the time—two and as many as three fiddles … but Bill was definitely the first … country artist that had two fiddles.”

“… it’s just like this with his music. His songs don’t change and the titles don’t change but the music changes as the years go by because every year we change that music whether he knows it or whether he don’t—I’m sure he does, and he himself has changed so much in the last four years it’s incredible. The man’s playin’ a third more mandolin today than he was playin’ four years ago … and he’s more conscientious of what he plays … He concentrates strictly on his sound—the sound is one thing, the melody is another. Now, you can play melody for Bill and as long as you play it clean he’ll never say a word to you but if you play melody and maybe brush in a little somethin’ extra, if it’s good, fine, and if it’s bad he’ll not say nothin’ to you right then and there, but you know … I think that Bill has changed his music as much as any man … you take tunes like ‘Blue Moon’ and ‘Muleskinner’ and ‘Footprints’ … ‘Uncle Pen’ and all that … he has to stay in that same category of melodies and that don’t give him the right to leave those numbers when every place he appears they want those numbers … so all that’s left for him to do is to improvise the music, not the lyrics …

Kenny has lived in Nashville on and off for a number of years now—and we spoke some about the Nashville Sound.

“… when they added the strings … the orchestra [to Hank Williams records], this music that they put to his singin’ there was strictly off sheet music and every note of that was there just like it should be and what I’m sayin’—now I don’t know this to be exactly, I seriously doubt if Hank Williams could’ve took his guitar and played the exact notes that this orchestra was a-layin’ down there … the feeling is something else …”

“In every musician there’s always the will to play more and get more out of one number … and I think that these boys, your guitar pickers … can look back to Chester … he’s not only played the melody but he had the chords a-comin’ right with it … even your fiddle players and your banjo men are more conscientious about their melodies and their chord progression … I think that a lot of the boys was a-listenin’ to a lot of artists like … Glenn Miller’s band, stuff like that. I think they had a big lot to do with the advancement of country music … and Tommy Dorsey particularly.”

“Now the Osbornes … I think they’ve advanced bluegrass music quite a bit … really and truly if you get right down to it you’ve got to give those boys credit because their harmony is so accurate … they’ve got a different sound to their music than anybody else but yet … it’s grass … I think it [bluegrass music] will branch out into different sounds … There’s no reason in the world why a bluegrass band can’t get their own songs … I think that that’s the way that people get their starts …”

[This article was taken from a taped interview with Kenny Baker in September, 1968.]

Share this article

2 Comments

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Kenny Baker, his wife Audrey Sizemore, their 2 boys, Kenny Jr. and Johnny Lee lived next door to our family. My sister, Betty Elkins ,married Kenny’s youngest brother Thomas Paul Baker. We grew up hearing Kenny, Mr. Mullins and Slick Gallion practing music at Kenny’s. Later Bill Monroe and The Boys practiced at Kenny’s, too.

I am very proud of Kenny’s accomplishment. He “done real good!”

I met Kenny in 1964 at age 10. I was raised in Honaker VA. Our neighbor was Billy Fields a banjo player. Kenny and Billy Fields grew up in Jenkins together and remained life long friends. Kenny named his son Billy after him. My father Don Barrett was an original Lonesome Pine Fiddler that replaced Bobby Osborne. When Kenny left Bill in the early 60’s they would play music at our house all weekend. I chopped mandolin. I learned bluegrass early but I liked rock and roll better. Years later I moved to Michigan and as an adult I fell in love with bluegrass. I worked with Wendy Smith in Blue Velvet. Fortunately it led me to travel a lot doing shows with Monroe and Kenny. Kenny remembered Dad and found I was his son and Kenny and I spent time together at the shows. Kenny was the best fiddle player bluegrass ever had. I loved him and cherish his music. Good travels my friend. Condolences to all remaining famiy