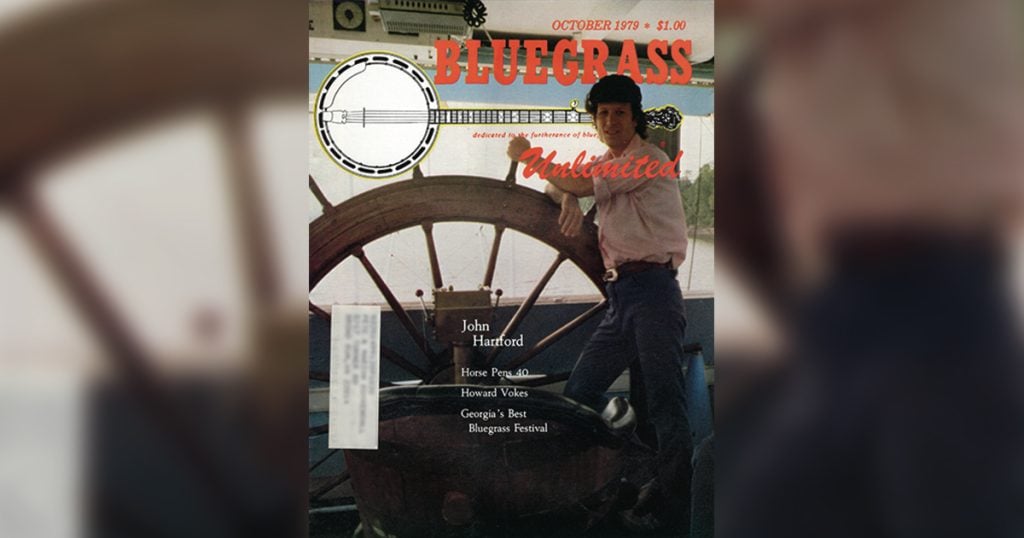

Home > Articles > The Archives > John Hartford

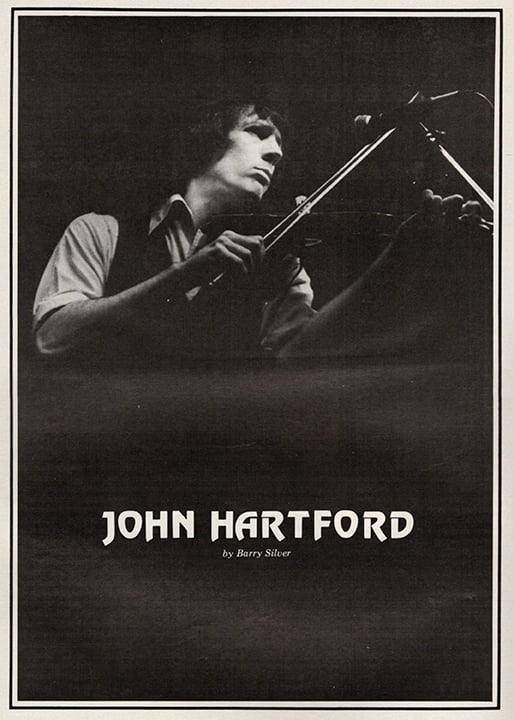

John Hartford

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

October 1979, Volume 14, Number 4

Regardless of how one has been introduced to John Hartford and his music: From back in the ‘sixties when he was appearing with the Smothers Brothers and Glen Campbell, through Campbell’s enormously successful version of “Gentle On My Mind” (not to mention recordings by numerous other artists), John’s own recordings and a concerts; or virtually innumerable words written about him in publications ranging from “People” to “Who’s Who In America. there are very few in this country who are unaware of him. Yet, even with the country band he usually records with, John Hartford has always been a bluegrass picker. “I express myself in those tones.” he once said. His early exploration of music in St. Louis is not untypical of those of many urban youth of the last few generations.

I must have been in the sixth or seventh grade when I started playing harmonica. I took a couple of mandolin lessons from an old mandolin teacher in St. Louis, George Krick. He had me playing out of an old Victor Herbert Songbook. I finally dropped out of that and started to pick out fiddle tunes I’d heard. I started thinking about playing banjo then, but I didn’t have one. Before long I found a banjo at a Goodwill store. It was a Vega Whyte Ladye and I bought it without a head on it for two dollars. It was a plectrum banjo, so I had a screw put in the side of the neck for a fifth string.

“My mother and father used to square dance and they used to dance to records mostly. They called ’em ‘square dances without calls,’ and I always liked the melodies on those records. Tommy Jackson had a record out, we had one by Cliffie Stone with Herman The Hermit — a big old 78 — and another one by a group called Woodhull’s Old Timers.

“My grandfather had an old fiddle that he played and he kept it in the closet of his house underneath some old coats. I had careful instructions not to mess with it; so I used to go into the closet and open up the fiddle case, get the bow and play with it when I wasn’t supposed to. I was probably eleven or twelve at the time. Later on I was in the National Folk Festival and I met Jimmie Driftwood. He had a fiddle and he tuned it to an open “A”. When I started playing that I found that I could get melodies easily, so I played for a while in open “A” tuning.

“The first banjo player I ever really got into that I knew by name was Stringbean. I used to like Herman The Hermit on the old Cliffie Stone records, but I didn’t know who he was at the time. We’d hear the Grand Ole Opry on the network — the Prince Albert portion — with Red Foley and Rod Brasfield and Stringbean on, and I used to wait for Stringbean. When I first heard Earl Scruggs it was a record, ‘Dear old Dixie,’ I think. At first I didn’t know what it was. maybe an electric guitar, and it took a couple of banjo breaks before it hit me full on. It was somethin’. It sounded completely different; I’d never heard anything like that before. Made me tremble.”

Within a few years, and while still a teenager. John was already a popular local sideman.

“I used to go around and work with different bands, sittin’ in with them, and a lot of times they’d want me to come over and play on their radio shows. On Saturday mornings all these bands would buy time on KSTL and go over there and perform. Each band would have fifteen minutes or a half-hour. Sometimes I would go in there and every band would want me to sit in on their segment playing a different instrument and I could wind up playing all morning long.

“There was a place in St. Louis called Compton Hall, and it was run by a lady named Diddy Woolsey and her husband, Pat Woolsey. Diddy heard me playing on, I think Curly Nelson’s show on KSTL, and offered me a job because she said I played fiddle like her husband. She already had a house band up there, so you weren’t really working for the band leader; you were working for Diddy. It was a big old hall on the third floor of an old building that was built before P.A. systems with a bandstand at one end of the hall. We’d play square dances, country, some rock ‘n roll and more square dances. We’d play two sets of maybe six or seven of them and try to get the crowd worn out. They had a lot of old country boys comin’ out from Southeast and Southwest Missouri who really liked to square dance and they’d have hinges on their shoes and taps that they’d put on loose so they’d make a lot of noise. Sometimes on the square dances Doug Dillard and Henry Lewis and Marvin Hawthorne would come up there and help me out and sit in and I’d play fiddle. Doug played banjo, then maybe we’d play some twin banjos and then the lead guitar would take it. Usually when one instrument took it I could switch off. On those square dances we didn’t want to stop, especially when we had a lot of good dancers out there. They didn’t want to mess around: They wanted to dance and we wanted to make it last for a while.

“Sometimes they didn’t have an electric guitar player, but they had an electric guitar there, or somebody in the band would have one. What I would do is tune the first string down, put it in banjo tuning, and play it with finger picks. When we’d have an electric guitar player I’d switch off between banjo and fiddle.

“Curly Nelson had an after-hours place in East St. Louis called The Stallings Athletic Club. Only private clubs could stay open after hours, and we all bought membership cards for a dollar. It was quite a place. They had bikers, and all kinds of disreputable characters in there — and all the musicians in St. Louis. We’d go there after work, get together on the bandstand and jam.

“About the time I was getting ready to go into the Army Doug and Rodney Dillard introduced me to Joe Noel. We played a lot together and had some publicity pictures taken together; but the record they made, which was Doug’s tune, ‘Banjo In The Hollow,’ was made while I was in the Army. I tried to get a pass for the weekend they recorded it, but I couldn’t. I wish I had, because I loved that record.”

After his hitch in the Army, John returned to St. Louis, and to his music. “I had a car and worked on the road promoting records, and I was in a band at the time called the Ozark Mountain Trio, with Don Brown and Norman Ford. We used to work every other Sunday on a television show in Qunicy, Illinois, with a guy named Toby Dick Ellis called the Possum Hollow Opry. While I was out on the road hustling records for this distributor in St. Louis I’d also be hustling dates for the Ozark Mountain Trio.

“KSTL needed a weekend announcer so I went and auditioned for the job and when they asked me what stations I’d worked for I gave them the stations where I’d played music. I had a friend at KSTL named Colonel Bill Green who came over the first morning and helped break me in and helped me learn how to run the board, do commercials and stuff like that. I picked that up pretty well and I was the weekend man for about a year and then went and got into full-time radio up in Clinton, Illinois, working for Uncle Johnny Barton at WHOW. WHOW was a great place because it was a five-thousand-watt daytime radio station and they did a lot of mail order stuff and they had live bands on weekends during the day. I played in one band on the station which consisted of Pat Burton, Nate Bray and Francis Bray.

“When I first went to Nashville I went to work at WSIX radio and I signed up with Glaser Brothers Publishing Company and started writing for them. They got some of my songs started and Chet Atkins heard and liked them and signed me with RCA Victor. He heard something different in my style and I started getting some session work through him. When ‘Gentle On My Mind’ came out, everybody who recorded it wanted me to play on their recording of it; and along with that I started getting more session work and I love it. I think the hardest thing and the thing that takes the most musicianship is doing record dates.

“I guess the first one of my songs that ever got recorded was by Jimmy Payne of Vee-Jay Records. The song was called ‘Every Little Pretty Girl.’ That was the first commercially recorded song of mine that I’d ever done in Nashville. It was produced by Bill Justus, with background singers and the whole thing.

“Roger Miller was a big influence on me, and so were John D. Loudermilk, Benny Martin and Bob Dylan. Most of my songwriting started out because I so dug the people I heard that I wanted to imitate them. As far as writing — he’s not a poetry writer or anything — I’ve always been very much into the writing of the river historian, Captain Fred Way, Jr. If he could write songs he’d be my favorite songwriter.”

John’s songs caught the attention of Tom Smothers, who at the time was scouting writers for the network television show he was doing at that time.

“Tommy Smothers heard one of my albums and hired me to move out to Los Angeles to write for the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour. When I got there he said, ‘I’ve got this guy and I’m going to have him host my summer show and I want you to meet him,’ and it was Glen Campbell.

“The first writing for the Smothers Brothers show was to write the summer replacement show which they called the Summer Brothers Smothers Show, starring Glen Campbell. I was the script writer and I just wrote myself into the script.

“I had ‘Gentle On My Mind’ out on a single of my own and it was doing pretty well on the West Coast. Glen Campbell heard it on the radio while he was finishing up some songs for an album and he recorded it.”

The Smothers show was the last time John wrote on a schedule. Since then he has made the world his workshop.

“I work all the time. I work on three- by-five-inch index cards; I carry them around in my pocket and I do everything on them. I write longways so I can put them in my hand and put my palms together and write. I can write while I’m walking or standing in a line or riding in a car — which is really handy because you can’t write any other way in a moving car. I can utilize my time better that way. I carry a pack with me and I’m constantly weeding stuff out of that and putting it in a little file. Luckily someone told me a long time ago that I should never throw anything away, so I don’t and that has paid off.”

January 1979 saw John (accompanied by managers Keith and Penny Case) make his first tour of Japan.

“It was real nice. I learned a lot. The weather was cold, but it wasn’t as cold as we expected. It was sunny most of the time we were there, and we were told that it was unusual. We went to Tokyo, Hiroshima, Osaka, Nagoya, Kyoto and then back to Tokyo. I loved it.

“I was very impressed by the whole way they used space over there, particularly in the stores. I went into Kawase Music in Tokyo, which is essentially a very small store with a huge inventory on display. All the guitars and banjos were hung within an inch of each other and all very carefully labeled, lit and displayed. It was really an eyeful to see something like that. In Tokyo, where they seemingly don’t have any crime, I was impressed to see the amount of stuff that’s displayed right on the street that you would never see in this country. I was impressed particularly with how clean everything was and the way space was utilized. I appreciate that from being on boats, because on boats the utilization of space is very important.

“The audiences surprised me on several counts, one being that I didn’t expect them to be as good timekeepers as they were. I went to Germany some time ago and played for the Germans, and they just didn’t cut it. They’d start clapping along on a fiddle tune or something like that and they’d start slowing down and getting all crazy. The Japanese people were right on the money; even in auditoriums where I would expect the beat to slow down a little bit they kept it up, kept it lively and sang along with the ones they knew.

“The first couple of shows I had some index cards where I’d written out various ways of saying things like, ‘watishito ishoni watase kudesai’ for ‘sing with me;’ and, ‘mosihito’ for ‘repeat with me.’ Sometimes I’d try to say that in English and if they couldn’t understand I’d have the cards for backup, but most times I could say that in English and it’d work. On a lot of songs that weren’t sing-along’s I could tell that there were people in the audience who were singin’ right along with me, but at the same time I met a lot of people who didn’t understand any English. They understood the songs and knew about bluegrass music and everything like that, but when I’d try to converse with them it was real hard and we were constantly running up on things where we’d just have to look at each other and laugh, because both of us would know what the problem was.

“Usually there was someone around who could speak English, but I did several sound checks where I was on my own and none of the sound people spoke English. The first couple of sound checks I didn’t know what to think, because I went in to work with the crews and we just did everything in sign language, pointing and showing and everything like that and it all went very smoothly.

“I got really fascinated with the language over there and a lot of times when I’d meet people who had the time they’d write their names out for me and then I’d have them write it out in Kanji or Katakana and then I’d start to try to read the signs while I was over there. It was real easy to figure out what the signs in the railroad stations were for ‘entrance’ and ‘exit.’ I worked on those and I looked in the book to find out what the symbol was for ‘car’ and things like that and I got to where I could start picking those things out in signs.

“The signs in Tokyo are amazing, because I really think the writing is beautiful, especially the Kanji; they write all over everything. In fact, I saw a guy drinking a cup of tea and the whole inside of the cup was filled with writing, around in circles all inside the teacup.

“If I had tried to study Japanese here in this country I wouldn’t have been able to make heads or tails of it, but when you’re in the country all of a sudden it’s all around and these things are happening and you can pick it up. I have a tendency to start imitating my surroundings like a chameleon and when I was over there I was able to do quite well.”

Immediately upon his return from Japan, John went back to his busy performing schedule, which brought to mind the question of where his favorite places are to work.

“I like a room with a fast sound like a dance hall. I like the Cellar Door in Washington, D.C.; The Golden Bear near L.A. is good; I like the Great American Music Hall in San Francisco, and the cabin of the “Julia Belle Swain” is great.”

With so many people having recorded his songs over the years, one might wonder who John might like to hear singing his material who has not already been doing so.

“I wish Peter Frampton would record a whole album of my material. Then what he misses, Fleetwood Mac could scoop up.”

No matter who records John Hartford’s songs, John himself will continue to write and record them, delighting audiences and making friends worldwide. John’s crowds will find his shows highly enjoyable because John himself finds them fun to do, and that enjoyment is contagious.