Home > Articles > The Archives > Sally Ann Forrester

Sally Ann Forrester

The Original Bluegrass Girl Pulling Her Own Weight With the Blue Grass Boys

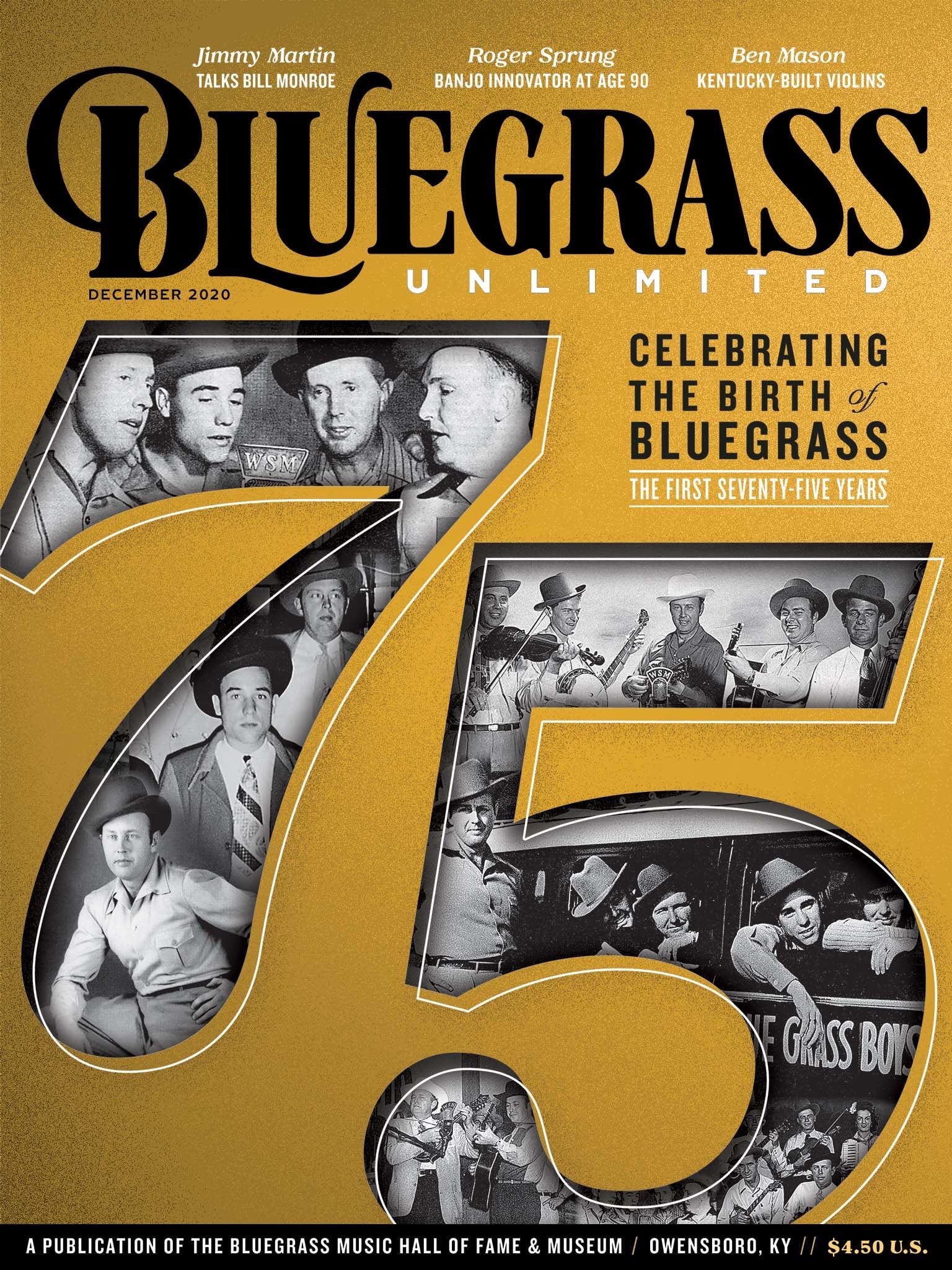

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

June 2000, Volume 34, Number 12

One of the standard beliefs about bluegrass music is that, in its formative years,bluegrass was “almost completely a male domain,” as Bufwack and Oermann describe itin Finding Her Voice: The Saga Of Women In Country Music. This belief tends to obscurethe fact that there have always been women in bluegrass music. But because they havebeen wives, girlfriends, sisters, or side musicians, the contributions of these players havebeen largely overlooked by historians and fans.

One of these women is Sally Ann Forrester who played with Bill Monroe and the BlueGrass Boys from 1943-1946. She not only played with Monroe, she was on the firstrecordings that the band made for Columbia Records in February 1945. These eightnumbers included “Kentucky Waltz,” “Footprints In The Snow,” “Rocky Road Blues,” and“True Life Blues.” Yet little attention has been paid to Sally Ann. Why? Basically, for threereasons: one, she was a woman; two, she was the wife of fiddler Howdy Forrester, whoalso played with Monroe; and three, she played the accordion.

Because Sally Ann played with Monroe while Howdy was in service, her presence inthe Blue Grass Boys has been dismissed by the explanation that she was hired to holdHowdy’s place in the band. How many of us fell for that line? One version of that rumoreven made it into print. Mark Humphrey, in his notes to the Columbia boxed set “TheEssential Bill Monroe,” writes, “The woman arrived as a package deal with fiddler HowdyForrester, and it’s been suggested Monroe kept her on as a favor to Howdy when heentered the Navy.” To suggest that Monroe might have kept Sally Ann on as a part of hisshow—for three years—as a favor to her husband is insulting. The statement suggeststhat Sally Ann was not worthy of being hired on her own. From what I know about BillMonroe, he does not strike me as the kind of man who would hire any musicians unlessthey could pull their own weight in the show.

The fact is, up until now, we have had little information about Sally Ann’s life. And thatinstrument, the accordion. In today’s lingo, “What was that about?” Recently, as part ofmy Master’s degree, I wrote a 125-page paper on Sally Ann. With the help of her son,Bob, and Howdy’s brother, Joe, who played with Sally Ann and Howdy for years, I learneda lot about Sally Ann. In this article, I concentrate on the aspects of her life that are ofinterest to bluegrass lovers.

Playing with the Blue Grass Boys was by no means the first musical job that Sally Annhad held. By the time she landed in Monroe’s band, she was a seasoned professionalmusician and entertainer, and had been playing music all her life. But because she wasraised in Oklahoma and did her first professional work there and in Texas, her musicalbackground was western-flavored. Her favorite group? Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys.

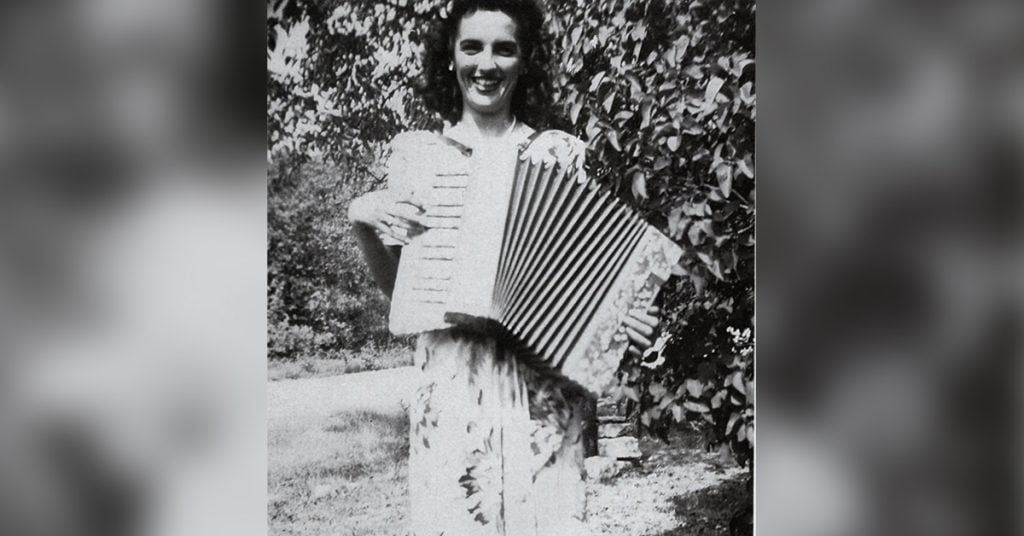

Born on December 20, 1922, in Raton, N.M., Sally Ann’s given name was Goldie SueWilene Russell. She was raised as an only child in Avant, Okla., near Tulsa, by hermaternal grandparents who called her Wilene, pronounced “ Will-een. ” (In this article Iwill refer to her as Sally Ann, the stage name given to her by Bill Monroe.) Her mother,who died of tuberculosis when Sally Ann was just 3, played piano and violin, and hergrandfather, George Robbins, played fiddle. By sixth grade, Sally Ann was playing piano,violin, and guitar. In 1939, when she was 16, she met Howard “Howdy” Forrester, 17,who had come to Tulsa from Tennessee with Herald Goodman and the Tennessee Valley Boys. The band, which included Howdy on fiddle, his brother Joe on bass, Georgia SlimRutland on fiddle, Curt Poulton on guitar, and Arthur Smith on fiddle, had arrived in townto start a barn dance and play on KVOO. The barn dance, the Saddle Mountain Roundup,debuted on April 1, 1939, and by June, Sally Ann was part of the show. Billed as the“Little Orphan Girl,” she played the guitar and sang, with the Tennessee Valley Boysbacking her up. Occasionally she played triple fiddles with Slim and Howdy.

The Saddle Mountain Roundup lasted only a year. In March of 1940, the TennesseeValley Boys found work at KWFT in Wichita Falls, Tex., while the Little Orphan Girlremained in Tulsa. Buton May 31, 1940, she received a telegram that read: “Comeprepared to stay. Bring fiddle. Howard Forrester. KWFT.”

“And she did,” said Bob Forrester. “For 47 years.”

After Sally Ann and Howdy’s marriage on June 29, 1940, she joined the Tennessee Valley Boys at KWFT, performing once again with her guitar as the Little Orphan Girl. Sheand Howdy and Joe played together at several different radio stations in Texas andIllinois until May 26, 1941, when Joe received his draft notice. Sally Ann and Howdyworked around Texas until Pearl Harbor was bombed, when they moved back toNashville. There, Howdy signed up with the Navy and waited for his draft notice. It cameon August 8, 1942, and Howdy went into service in the spring of 1943.

This, then, is Sally Ann’s early musical life. Notice what is missing: the accordion. Joe Forrester says she did not get an accordion until after Howdy went into the service. Now we come to the bluegrass period of Sally Ann’s life. Did she, in truth, arrive in the BlueGrass Boys as “part of a package deal” with Howdy? I don’t think it was that simple.

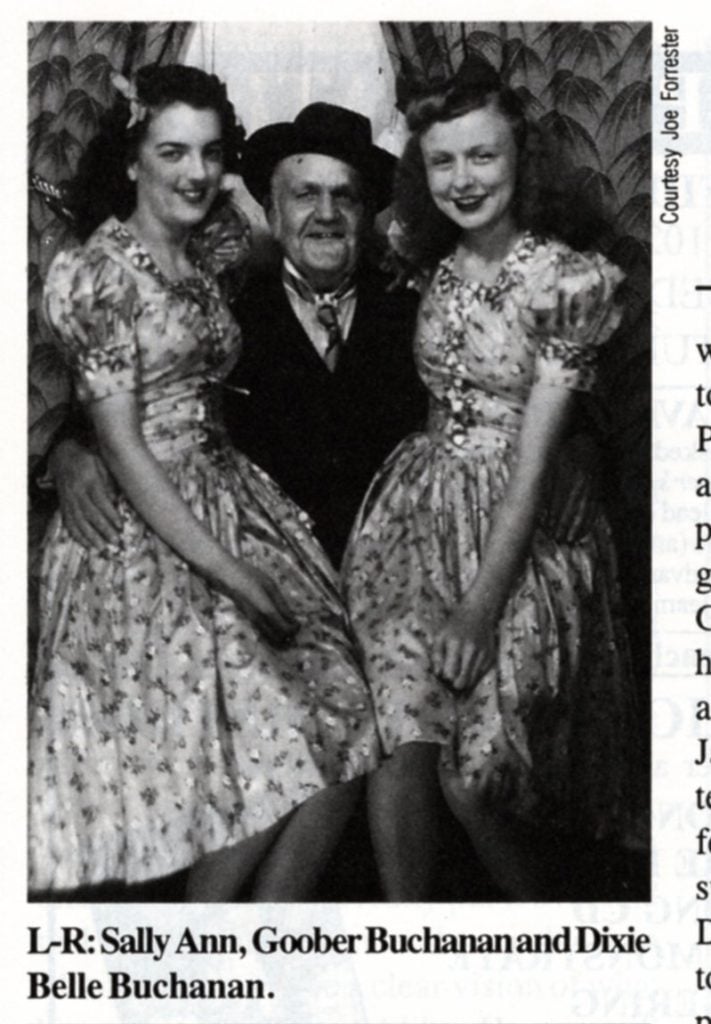

Thanks to Goober Buchanan, we now know part of the story. Goober and his wife Dixie Belle actually worked with Sally Ann and Howdy when they were part of Jamup and Honey’s 1942 Grand Ole Opry tent show. Goober tells the story this way: He says that heand Dixie Belle were working at WHOP in Hopkinsville, Ky.,staying with them until hewent into service. Sally Ann probably continued on as a solo act with the tent show. We know from a letter Uncle Dave Macon wrote to Goober that Sally Ann and Howdy were both still with the tent show through November. She was not yet, however, a member ofthe Blue Grass Boys; pictures of the band at this time include only Monroe, Howdy,Stringbean, Clyde Moody, and Cousin Wilbur [Wesbrooks].

We do know, of course, that at some point Sally Ann became an official member of BillMonroe’s band. But when? And why? I think Sally Ann’s hiring was pretty straightforward.Howdy went into the service around the end of March 1943. But fiddle players could beeasily replaced, and Howdy was replaced almost immediately by Chubby Wise. But thiswas just about the time that Monroe was getting ready to take out his own tent show forthe first time. He would have wanted a strong show with a lot of variety. From working with Sally Ann on the 1942 tent show, Monroe would have known that she was a seasoned professional entertainer who could pull her own weight with the show. If Howdy had not gone into service, no doubt both he and Sally Ann would have been working the tent show again in 1943. But just because Monroe couldn’t have Howdy, it ismore likely that Monroe hired Sally Ann because she was a proven asset to the tentshow.

A letter from Howdy, dated May 15, 1943, shows clearly that Sally Ann was workingwith Monroe at the start of tent show season: “Hope you are working alright now. Isuppose you are counting money and tickets for the tent show by now…Tell Bill and allthe boys hello forme.”

That Sally Ann was originally hired only for tent show season is confirmed by a letterfrom Howdy postmarked September 4,1943. She and Howdy did not know if Monroe would keep her on once the season was over. Howdy writes, “I hope you can keep onwith Bill and the boys throughout the winter…” “Throughout the winter” would havemeant after tent show season which ended in November.

Even though we now know Sally Ann was with the 1943 tent show, we still do notknow when she started playing the accordion. The earliest publicity picture of Sally Annwith the Blue Grass Boys (Monroe, Chubby Wise, Curley Bradshaw, Clyde Moody, andStringbean) does not show an accordion. All the other band members are holding theirinstruments, but Sally Ann is positioned, without an instrument, in front of themicrophone, as if she were a featured singer. Perhaps she played the guitar, as she had done with the Kentucky Sweethearts, Joe Forrester thinks that it was Sally Ann herself who eventually suggested to Bill Monroe that she play the accordion on the show. This makes a certain amount of sense because, if Sally Ann had never played accordion before, how could Monroe have known that she played? She would have been the one torealize that since she played piano, she could make the switch to the accordion with littletrouble.

Howdy was keeping up with the band by listening to the Opry. On August 30, 1943, hewrote: “I listened to the Opry Sat. nite. It sounded about as usual…Bill’s program was fairenough but String Bean’s leaving really left an empty spot in it. It was really good to hearthem though. I didn’t hear the first program…” The reference to “them” makes me thinkthat, in August 1943, even though Sally Ann was a part of the tent show, she was not yetperforming with the band on the Opry.

By October, however, she had definitely hit the big time—she was appearing on theOpry. In a postcard from Tulsa, Okla., dated November 2, 1943, an old friend writes, “Weenjoyed hearing you sing the last two Sat. nights [October 23 and 30].” The fact thatSally Ann begins to appear on the Opry so close to the end of tent show season is worthnoting. I think that by now Monroe had decided to use her through the winter, and thatperhaps this decision coincided with the decision to use her on the accordion. I also find it significant that Roy Acuff had added Jimmy Riddle on accordion (and harmonica) in September 1943. Perhaps it was the addition of the accordion to Acuff’s band that gaveSally Ann (or Monroe) the idea to try the accordion in the Blue Grass Boys. Unfortunately,the accordion remains the most puzzling aspect of Sally Ann’s musical career.

In Ralph Rinzler’s chapter on Bill Monroe in Stars Of Country Music, Rinzler wrote,“Bill has said that the inclusion of the accordion…was directly traceable to his memory ofhis mother’s playing.” But Monroe’s mother, Malissa, also played harmonica and fiddle. Monroe’s addition of Curley Bradshaw on harmonica is not tied to a memory of Malissa Monroe’s playing. I find this answer too simplistic. I think when Bill Monroe wasconfronted with the question “Why the accordion?” he gave an easy answer that was notlikely to be questioned. A more realistic answer might have revealed that, at the time,Monroe was trying anything that would work.

Mark Humphrey says that in an “unguarded moment” Monroe “is said to haveremarked of the accordion, ‘I tried anything to get something that would sell.’” ThatMonroe would add an accordion because he thought it would sell is very believable.Monroe was very conscious of having to please the audience. In a 1979 Frets interviewhe said, “Well, I wanted them to accept [my music], ’cause I knew I had to have [theaudience] on my side if I was to really put it over and make money at it.” Remember, atthis time Monroe did not have a clear vision of what his music should sound like. He wasstill experimenting. Since Sally Ann was already with the show, this would have been aperfect opportunity for Monroe to try the accordion. The experiment obviously provedsuccessful—Sally Ann stayed on with the band until the early part of 1946.

From Sally Ann’s performances on the Opry we know some of the songs she sang: “PutMe In Your Pocket,” “Goodnight Soldier,” “I’ll Have To Live And Learn,” “Bury Me Beneath The Willow,” “Sweet As The Flowers In May Time,” “Sailor’s Plea,” “If It’s Wrong To LoveYou,” “Heading Down The Wrong Highway,” and “I’m Just Here To Get My Baby Out OfJail.” We don’t know for sure if she sang regularly on any of the trios or quartets, but thefact that she sings tenor on Monroe’s 1945 recordings of “Come Back To Me In MyDreams” and “Nobody Loves Me” (both unreleased until the 1980s) indicates that attimes she probably did.

In February 1945, Sally Ann went with the band to Chicago to record eight numbers, all in one day: “Rocky Road Blues,” “Kentucky Waltz,” “True Life Blues,” “Nobody LovesMe,” “Goodbye Old Pal,” “Footprints In The Snow,” “Blue Grass Special, ” and “Come Back To Me In My Dreams.” These songs have determined Sally Ann’s stature in thebluegrass world. Some fans love these recordings; others dismiss them with a shrug as“not really bluegrass” because they don’t feature the Scruggs-style banjo.

Of these eight songs, four feature the accordion prominently: “Kentucky Waltz,”“Rocky Road Blues,” the alternate take of “True Life Blues.” and “Blue Grass Special.” On“Kentucky Waltz,” the instrumental break comes very close to being a duet with thefiddle. Sally Ann follows Chubby Wise’s fiddle lead-in almost note-for-note with theaccordion before she breaks into a harmony which continues throughout the break. Theaccordion also provides the “color” chords such as sevenths, sixths, and minors, whichthe guitar does not play.

In “Rocky Road Blues,” the accordion provides seventh chord transitions (from the Ichord to the IV), this time following Monroe’s voice which often goes to the seventh note.Jim Shumate, who was the fiddler in the band later in 1945, noted that Sally Ann was“good at following her voice with the accordion.” The accordion also plays off-beatchordal backup through much of the song. In the alternate take of “True Life Blues”which is now available, the accordion is quite prominent. As soon as the mandolin beginsthe introduction to the song, you can hear the accordion playing some rather insistentchords on the off beat. It is almost as if Sally Ann is trying to help the rest of the bandfind the rhythmic groove. She continues to add color to the sound, this time frequentlyadding the seventh note to the V chord.

“Blue Grass Special” features breaks by all the instruments. This tune, more than anyother, indicates that Sally Ann was a capable instrumentalist and a full- fledgedcontributing member of the Blue Grass Boys. Her solos are substantially the same on both the released version and the alternate take, issued in 1992, while Monroe and Chubby Wise played somewhat different solos on each version. Mark Humphrey statesthat “[t]his underlines the obvious: All the band members had prearranged solos, butonly two of them (Wise and Monroe) could improvise.” Bluegrass music is, by its verynature, improvisational. No one, especially back then, learns to play these tunes (and allthe backup) by reading notes. Sally Ann certainly could improvise on the accordion. Ifshe chose to play the same solo on both takes of “Blue Grass Special,” perhaps she wasonly being the “consummate pro” that Humphrey earlier called Chubby Wise for “playingthe same break each time” on “True Life Blues.”

The two vocal trios from this session, on which Sally Ann sings tenor, were notreleased until years later: “Come Back To Me In My Dreams” in 1980 and “Nobody LovesMe” in 1984. (An alternate take of “Nobody Loves Me” was released in 1992.) There is noaudible accordion on either song, but Sally Ann’s tenor blends nicely with Monroe’s leadand Tex Willis’s baritone. These two numbers indicate that Sally Ann was a part of theoverall vocal sound of the band. Of particular interest is the fact that these were the firsttrios Monroe ever recorded. (Sally Ann was accustomed to singing in trios—she andHowdy and Joe had always featured trios on their shows.) More importantly, thesenumbers defy what would come to be the stereotypical bluegrass trio composed of threemen, one of whom sang tenor. Here, Sally Ann sings tenor to Monroe, as she would have had to with her higher voice. I can think of no other instance when anyone on recordsang tenor to Monroe. It is therefore a real shame that these recordings remainedunissued until the 1980s. If these numbers had been issued back in the ’40s or even’50s, people would have heard a woman singing bluegrass right from the beginning.

Howdy got out of the service in November and, in December 1945, rejoined the band,which included Sally Ann, Earl Scruggs, Lester Flatt, and Joe Forrester on bass. Buteventually the rigors of the road led Sally Ann, Howdy, and Joe to quit Monroe in March1946. At 23, the bluegrass period of Sally Ann’s life was over. A new era in her life wasjust beginning, however—she was pregnant. On January 4, 1947, Sally Ann and Howdy’sonly child, Bob, was born.

In 1946, Sally Ann, Howdy, and Joe continued to work together, first back in Tulsa withArt Davis and the Rhythm Riders. But in June, they headed for Dallas where Slim Rutlandhad reorganized the Texas Roundup on KRLD. Although Sally Ann was originally not partof the Roundup, due to the lack of money for additional musicians and possibly herpregnancy, by the middle of 1947 she was playing accordion with the band, both on theradio and for the dances they held at Bob’s Barn.

In November 1947, Sally Ann filmed some movie shorts with Rambling Tommy Scott,of medicine show fame. These short clips, made to be shown in theaters before featuredmovies, and now available on video, give us our only chance to see and hear Sally Annperform on the accordion. It is obvious from watching these shows that Sally Ann is aterrific musician. Her swinging, bouncy accordion playing—all improvised, I’m sure—isthe instrumental foundation of the music; it carries the band. She plays most of theintroductions as well as most of the leads, and her backup holds the music together likeglue. She was also quite the show person. She comes alive on stage and simply exudespersonality and a sense of fun.

Howdy and Sally Ann worked in Dallas until 1949, when they, along with Joe, movedback to Nashville. Joe got out of the music business and took a job with the Post Office;Howdy took a job fiddling with Roy Acuff in October 1951 and worked for Roy until 1987.Sally Ann passed the Civil Service Exam and worked for the Social Security Administration for 30 years. She and Howdy continued to play music with their friendsfor fun. As Bob Forrester said, “Mama loved to play…It was a standard thing to play atfamily gatherings, and we had a lot of family gatherings.” Howdy Forrester died ofcancer on August 1, 1987. During the last years of her life, Sally Ann developed Alzheimer’s disease. She died on November 17, 1999, in a Nashville nursing home withher son Bob at her side.

Sally Ann became the “original bluegrass girl,” in part, because she was in the rightplace at the right time. We know now that she was hired not as a “favor” to Howdy, butbecause she was a talented entertainer in her own right. Unfortunately, her singing was not heard on record until the 1980s, obscuring the fact that women had a “voice” in bluegrass music from the beginning.

Like many male musicians, Sally Ann was driven to play by something inside herself. She loved music all her life. That she quit the music business while Howdy continued toplay does not seem to be particularly gender related. As Robert Coltman points out, it is“rather typical for a country artist to quit performing after five or six years, to settledown, raise a family, and go to working steadily at something near home.” Except for the year of her pregnancy, her musical career, in many aspects, is not too different from that of many men. Sally Ann’s life should be a reminder to us all that bluegrass has neverbeen exclusively “man’s music.

Women have been there all along. The time is ripe for us to begin recognizing thecontributions that women have made to this music we all love so well.

Murphy Henry publishes the quarterly newsletter Women In Bluegrass, writes amonthly column for Banjo Newsletter, writes the General Store column for BluegrassUnlimited, helps run the Murphy Method, and in her spare time plays the banjo.