Home > Articles > The Archives > BILL MONROE: KING OF BLUE GRASS MUSIC

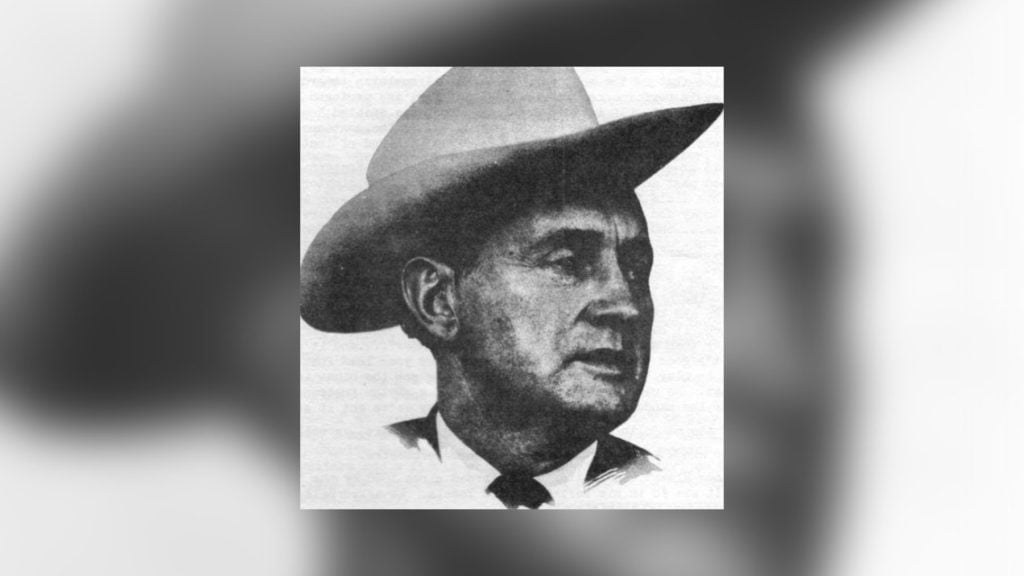

BILL MONROE: KING OF BLUE GRASS MUSIC

Re-printed from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine from a four-part series run in 1967 and 1968

Radio McGill series. Interviews conducted by Doug Benson. Series researched, written, produced and announced by Doug Benson (with production & technical assistance from Richard Adams and a cast of thousands). Following is the first installment of a series containing material transcribed by Doug Benson from tapes he put together for the student radio station in his final year at McGill University in Montreal. The announcer’s intro will fill in the necessary background. (Recurring abbreviations are: BM for Bill Monroe; bg for blue grass; BGB for Blue Grass Boys; ANNCR for Announcer; db for Doug Benson.) (As you will notice, I am one of those who like to see blue grass written as two separate words; I would prefer that my orthography be left unaltered in this respect. —db)

PROGRAM #1 — BLUE GRASS MUSIC PAST AND PRESENT

ANNCR (over BM instrumental): RADIO McGILL presents BM: KING OF BG MUSIC ….a series of programs about the man who pioneered the original bg sound, thus introducing a new and vital element into country music. BM is one of the most significant figures in the realm of indigenous American music because he has carved out—almost single-handed—a new style of music that has subsequently been taken up by others on a large scale….He is the definitive bg mandolinist and the definitive bg singer….Monroe’s soaring tenor voice and a marked blues influence have led to the use of the phrase “high, lonesome sound” in reference to his music.

When BM and his BGB were appearing in Montreal in November of 1966, RADIO McGILL conducted extensive interviews with Monroe himself and with two of his sidemen—fiddler Richard Greene and lead singer-guitarist Pete Rowan—both city born and bred and both highly articulate young men. Leader and sidemen were interviewed on separate occasions so as not to inhibit the speakers in any way….When you do hear their voices juxtaposed, it is only as a result of subsequent editing of the tapes.

BM’s attitude is like that of the most serious classical musician toward his music. In conversation as well as in performance his great respect for, and profound belief in his music become immediately apparent. It is this conviction that has enabled Monroe to resist the trends of Nashville throughout the years. BM stands out on the contemporary country music scene as “the man who won’t sell out”! (Music level up till end of instrumental)

ANNCR: This initial program we have entitled BG Music Past and Present. And BM is the unifying thread between past and present in bg music: he is the originator and has been the driving force in this field for more than a quarter of a century….He is still the best all-round bg musician today and shows no sign of letting up….In our interview with Bill, we asked him what bg music is….and what elements have gone into its composition.

BM: To start with, I wanted to have a music different from anybody else; I wanted to originate something. I wanted to put all of the ideas that I could come up with, that I could hear of different sounds…and of course I’ve added the old Negro blues to bg. And we have some of the Scotch music in it—the bagpipes….and we also have hymn-singing—you’ll notice that down through the melodies and through bg. Starting with numbers like the “Mule Skinner Blues,” when I first started, it had a timing to it—the beat—that just fit perfect for what I wanted to do….It’s faster than most people would do “Mule Skinner”….and it’s in a time that you could dance by. It’s good to listen to and it’s good for your lead instruments like the fiddle to play the music, to play “Mule Skinner”….’cause it’s got the blues in it and it just makes it perfect like that. We use the mandolin as a kind of a rhythm instrument in the group, and it sets perfect for the mandolin to keep the time the way we’ve got it arranged.

db: The rhythm of the mandolin adds a lot of drive to the music, as well.

BM: Yeah—it works kinda like a drum would work in an orchestra.

ANNCR: “Mule Snner Blues” was written and recorded circa 1930 by the “Singing Brakeman,” Jimmie Rodgers….It was #8 in his series of Blue Yodels. We asked Bill where he got the idea to record his own version of this song.

BM: Why, Jimmie Rodgers—he was the first to come out with yodel numbers that I ever got to hear….He could sing ’em so good: had a wonderful voice and he played a good guitar. I always liked his singing and playing, and I guess that’s how come I wanted to do “Mule Skinner”….I wanted to put the new touch to it, and I wanted to have a different yodel from what he had. You know, I have a yodel with “Mule Skinner”—it’s got a little laugh on the end of it….and when I seen that it would sell—that little yodel would help sell the number—why, I knew then we had something going that would be to my advantage on down through the years….with the timing of that number and everything. And with the BGB, it’s been kinda like you going to school—you’ve got a good teacher over you, somebody that knows what you should do and what shouldn’t do….so we have had to kinda set a pattern with bg….and of course each year, why, I have brought out a little something different as we’ve gone along.

Something that’s helped me and helped bg—I have had a lot of different people to work for me. I’ve been in it 27 years now….and I like the friendship of a man, but I don’t think I would’ve liked to have kept the same musician for 27 years, because his ideas would run out….and to bringing in new men along to learn to play bg, with their ideas, why, it’s helped advance it along each year.

ANNCR: We asked Bill how he first became interested in music as a young boy.

BM: My mother could sing and she could play a fiddle. Of course, I really learnt to play from my Uncle Pen Vandiver. I can remember hearing them play, and I would try to sing off to myself where nobody could hear me….and I knew that someday I could sing a song like the “Muleskinner” —or any country song—because my voice would be a high voice and could do that.

ANNCR: There are two distinct influences which BM recalls from this period of his life and both of these are clearly manifested in his unique musical style. His mother’s brother–Pen Vandiver—was a fiddler of considerable talent and local renown.

Bill often talks of childhood memories of his Uncle Pen fiddling “lonesome tunes”….and the importance of his Uncle Pen’s playing—plus the blues influence of Arnold Schultz— overestimated in the subsequent development of Bill’s “high, lonesome sound.”

In response to a question, Bill reminisces about his Uncle Pen….

BM: He played for a lot of square dances in Kentucky….There wasn’t many musicians around and. back in the early days I had to learn to play a guitar; he would let me go along with him to play guitar while he was playing the fiddle….and we’d make from two dollars-and-a-half up to five—never over five dollars a night. So I really have to give him a lot of credit for my playing and really, I guess, the roots of bg.

ANNCR: At one of the dances where Bill was backing up his uncle on guitar, he met Arnold Schultz, a Negro fiddler and guitar picker whose name is almost legendary in that country. The young Monroe was greatly impressed with Schultz’s playing….and although he did not sing, Bill recalls that he could “whistle the blues” better than anyone around.

BM: It was about the last days that I spent around in Kentucky—I left there when I was 18—and I had got acquainted with this old colored man that played a guitar, and he could play some of the prettiest blues that you ever listened to. He also could play a fiddle and me and him has played for some dances, you know, just the fiddle and guitar. But that’s where the blues come into my life—hearing old Arnold Schultz play ’em….He was the best blues player around in our part of the country there in Kentucky, and that’s where most of the people that plays a guitar today—that’s all come from old Arnold Schultz: it come on down through Mose Raglan Rager), from him into Merle Travis, and from him into Chet Atkins….that’s where all that style of playing come from.

db: Now with your musical talent, you could no doubt have excelled on any number of instruments. Why did you choose the mandolin as your specialty?

BM: Well, there was three of us brothers, to start with, that tried to play music….and of course they was older than I was and one of ’em (Birch) wanted to play the fiddle. Following him was another brother, Charlie Monroe, and he of course loved the guitar….and we knew that there shouldn’t be two guitars and a fiddle or two fiddles and a guitar, so it left me to get some other instrument….and the banjo wasn’t to be heard of then much—there was a few played it—and no bass fiddle at all hardly. So I got the mandolin; I wound up with that.

ANNCR: I couldn’t help but chuckle as Bill explained why he took up the mandolin, but it’s really a sobering moment when you stop and consider that there very nearly was no mandolin in bg music….and that the man who literally put the mandolin on the map arrived at his choice of instrument strictly by the process of elimination!

BILL MONROE: KING OF BLUE GRASS MUSIC: PART 2

Following is the second installment of a series of articles transcribed by Doug Benson from the original tapes of the Radio McGill shows he wrote, produced and announced last year.- (Recurring abbreviations are: BM for Bill Monroe; bg for blue grass; BGB for Blue Grass Boys; ANNCR for Announcer; db for Doug Benson.) Interviews conducted by db (with production and technical assistance from Richard Adams and a host of skilled operators).

PROGRAM #1 — BLUE GRASS MUSIC PAST AMD PRESENT (continued)

ANNCR: In his article on BM in Sing Out I (March *63), Ralph Rinzler makes it clear that Bill’s unique and original mandolin style was the result of conscious effort on his part. BM deliberately set out to pioneer a style all his own (having determined at age 13 to do so), and there can be no doubt that he has succeeded brilliantly.

BM: Learning to play the mandolin, Doug, that’s something else that I would like to tell you. In originating bg music I originated a different style of a mandolin. I wanted to be sure that I played a different style from the other people through the country that played a mandolin. So that’s worked in with bg, too—it’s been a big help to bg.

db: You’ve been a great innovator on the mandolin, and of course the instrument that a musician plays is important to him. Tell us about your mandolin—it’s famous in itself. When and where did you get hold of it?

BM: I found that mandolin in Miami, Florida (about 25 years ago, I guess). It was in a barber shop laying in the window with a sign on it for $125. I needed a mandolin and so I wound up with that one.

db: Why is it that on your mandolin the place where the company name appears has been scratched

off ?

BM: Richard (Adams), he’s leading into something there! (chuckles)…Well, I tell you…the mandolin I have is a Gibson of course and I had to send it back to the factory—every time I’d need frets in the mandolin, I would get a new fingerboard put on it. And this time that I sent it back—the neck had been broke off; it needed a fingerboard; it needed re-finishing; it needed keys…it needed everything, mind you. So I sent it back and they sent it back to me with just the neck put back on and that was about all. I don’t know whether they just overlooked it or something and didn’t do everything I said or not. But it didn’t make me feel good, so I thought, well, I didn’t have to have the name of Gibson—they had never done much for me…But they have done a lot for other people and I guess it’s a good thing that I got this Gibson mandolin, because I do think it’s the best mandolin—especially for me—in the country.

ANNCR: One of the most important things in bg in the singing. Bill had some remarks on the vocal aspect of his music.

BM: I had worked with my brothers till I was 27 years old, and I had never sung the lead of a number I had always sung tenor. But starting the BGB, I wanted to do yodel numbers and solo numbers and still keep the tenor that I had learnt when we worked as the Monroe Brothers. So I’ve used duets and trios…and we’ve always carried the BG Quartet, too—because I do like to do a couple or three hymns in any concert, you know I was the first one to ever have a quartet in a string band down south. Could have been some other parts of the country that had them, but in our part I was the first one.

ANNCR: We asked Bill about the contribution his current fiddler—Richard Greene (November ’66)—is making to the music.

BM: Richard is adding a lot to bg—it’s hard to keep him from adding too much…Well, you could easy get bg to swinging, you know, and get it too modern…and I don’t want it that way. The biggest job of bg is to keep out what don’t belong in it.

db: When did the element of twin and triple fiddles enter into bg?

RG (Richard Greene): When Bill put it in (chuckles)…Ask Bill what the first one was—I

don’t really know.

BM: I was down at the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville and of course we rehearse a lot and this Saturday night there was a boy (Dale Potter, I believe it was) back there in our dressing room that could play a good second fiddle. So he got to fiddling with us and it sounded so good that I was gonna start on the Grand Ole Opry two weeks from that night with two fiddles—and one week from that night Hank Snow started with two fiddles…We use the same dressing room, Hank and I, and he liked it so well that he got two fiddles—Chubby Wise and Tommy Mack Vaden I believe was fiddling for Hank then.

db: What is the important thing in a bg fiddle player?

BM: Well, I think a fiddler—he should play all the old time fiddle numbers like they was wrote…and there’s a lot of different notes that fiddlers today don’t never learn—he skips through them, you know—and I think he should know all the shuffles and licks with the bow…I think that’s one thing that makes a good fiddler. And to be a good bg fiddler, you’re in a higher class for fiddle music than you would think about. It’s not like the old time square dance numbers that was made 30-40 years ago…With having the blues and everything that’s been added to bg—if he plays a good bg fiddle, he’s on up, you know…he’s really a good fiddler. Ain’t everybody that comes along can play a bg fiddle.

ANNCR: As we pointed out earlier, Bill’s fiddling uncle—Pen Vandever—was an important influence in his development as a musician. Bill wrote a song called “Uncle Pen”—it’s one of his all- time classics and Bill is justifiably proud of it.

BM: Now take the number called “Uncle Pen”, for instance—you know everything is in that number that should be in it, because it’s an old-time number and wrote about an old time fiddler and it’s a true song. You wouldn’t want to go to swinging on that number, you know, putting a lot of extra stuff in—because it would take away from the number…and you nearly know that that number’s got everything in it that it should have…

(Play “Uncle Pen” Side 1, cut 4 of BM’s Decca lp DL-4327)

ANNCR: Bill admires a few of the stars of commercial country music—

BM: —but there’s a lot of country music (they call it country music) today that I don’t like, that’s just out to sell a record and they think if they sell a record that they’re worth $1000 that night and they’re not, you know. I don’t like that kind of a musician….Some of ’em are the kind of people that if they made a little money out of it, they would still be an entertainer and make records, because they think that’s wonderful, you know….A man who plays music should do his best, because if you’re on radio or television, there’s so many thousands watching you and listening to you that it’s not something to just be played around with—I think it should be mastered.

Well, I never thought that electric instruments would work good in bg. Of course, people like Bob Wills—it’s got its place there, because they play for dancing and I think it’s a wonderful thing for them. But I don’t think it would be a bit of good for bg without you went all electric, you know, everything was electric.

Db: Then it wouldn’t be bg.

BM: No, I don’t think so. I can show you a lot of bg groups that has a lot of bg playing, but they don’t have any beat to their music…and I guess that drums probably helps them.

(Hit “Brown County Breakdown, hold for 12 seconds, then under)

BM: Doug, I have tried to keep bg, you know, not let it get out too far and I think that’s the reason the country people really went along with the BGB….And you know that bg has got a lot of expression in it—there’s no way around it, it’s got that.

(Music up for 15 seconds, then under for ANNCR’s extro…end of Program #1.)

(This series continues next issue with Program #2, BM: The Man & The legend—in which Pete Rowan and Richard Greene discuss musical genius, indestructibility, teaching and inspiration, religion, time and drive, sustained 7ths, etc. Any radio stations wishing to inquire about dubbing these shows, write Doug Benson, Apt. 70^, A-5 Qakmount Road, Toronto 9, Ontario, Canada.)

BILL MONROE : KING OF BLUE GRASS MUSIC: PART 3

Following is the third installment of a series of articles prepared by-Doug Benson, based on material presented in the Radio McGill shows he wrote, produced and announced a year ago, (Recurring abbreviations are: BM for Bill Monroe; PR for Peter Rowan; RG for Richard Greene; bg for blue grass; BGB for Blue Grass Boys; ANNCR for Announcer; db for Doug Benson.) Interviews conducted by db Vith production and technical assistance from Richard Adams and a horde of talented engineers).

PROGRAM #2 — BILL MONROE: THE MAN AND THE LEGEND

Hit “Roanoke” (Side 1, Cut 3 of BM’s Decca lp DL-4327) … then down and ANNCR over music: Welcome to Part 2 of the Radio McGill series, BM: King of BG Music. This program is entitled BM: The Man and the Legend…

BM: One thing about bg, Doug, that I don’t like about it: the more you talk about it, the more it sounds like you’re bragging on it I don’t want the people to think that about me, because I don’t like to brag.

RG: …Bill has always gone up and he’ll always go up until the end . It’ll take some great physical catastrophe to stop him. (PR: Like getting old.) No, I don’t think he’ll get old that way—I just can’t see it.

PR: Take a banjo player, a guitar player, a fiddle player and a bass player, and say they’re all competent musicians—and put them with Bill and here’s this driving force through all the other music in the band.

RG: He is possibly the finest musician, the man containing the most musicianship in the entire field.

ANNCR: On the first show in this series BM himself did most of the talking. On this program we will be hearing mainly from RG and PR, 2 members of Monroe’s band, the BGB. Leader and sidemen were interviewed on separate occasions so as not to inhibit the speakers in any way. When you do hear their voices juxtaposed, it is only as a result of subsequent editing of the tapes. (Music level up and sustain till end of “Roanoke”.)

ANNCR: There is definitely an aura of legend that surrounds BM. As RG sees it, this aura is two-fold.

RG: There are 2 auras of legend—there’s the urban and the rural…

db: Develop that—that’s very interesting.

RG: Due to his accomplishments and who he is and everything, Bill stands so high above all the country people that he comes in contact with and—I mean, he’s not condescending or aloof—it’s just that he has recorded for 30 years and in the music world of the country he’s just been the leader for so long and he’s done things that to them they could never conceive of doing…(pause) …well, maybe that explains it enough…

PR: …and he hasn’t slipped, either. He hasn’t succumbed to things like dope or drinking or any of the things that some of the modem country musicians have.

ANNCR: In the city the BM legend is a more recent phenomenon, since it wasn’t until the folk music boom in the early sixties that Monroe received any wide exposure in the big cities of the northeastern U.S. or on the west coast.

RG: It had been very hard to see him in person; all you had to go on were some stories and some records. By the time you did see him, you had this fantastic thing in your mind—I even had it myself when I first met him. In fact, when I first met him (January 27, 1966, an hour or so prior to stepping on stage as fiddler for the BGB in a concert at McGill University in Montreal – db), I didn’t even know it was him: I asked somebody, “Where is he?” Because here was this heavy, big guy and I thought of him as a little guy because of his high voice—I know these are ridiculous associations I had—and he was dressed very casually…they had made a very long road trip the previous day, and he was tired and sullen…and it was a tremendous shock to first meet him. Since I have gotten to know him, I can see from close quarters what kind of person he is and I have a great deal of respect for him, but it’s not at all the kind of respect I had before I met him—it’s now supported with experience.

One friend of mine in Los Angeles—when Bill played the Ash Grove—interviewed him on a tape recorder backstage and this was the greatest moment in his life. At the time it was traumatic because the cord of the tape recorder tripped Bessie Lee as she was walking into the place and she fell sprawling on the floor or something…this is how the thing started and he was helpless, the poor guy. Now that I know Bill, that was probably nothing but humorous to Bill—it was nothing to worry about at all When you don’t have the actual experience to relate to, all you have is hearsay and your imagination is much more free—I guess that’s all it amounts to….and there were stories going around. I’m not too good at remembering things—I just heard things about how he used to spoof Chubby Wise all the time one time he attacked him from behind as they were walking out of a restaurant, stories like this…or when somebody was driving a car and Bill wanted to get out for a minute and the car happened to be stopped by a cliff and Bill got out of the car and fell down the cliff…

PR: …got back in the car and said: “Drive on, boy.”

ANNCR: Is BM a religious man?

PR: He chooses religious songs—or some of them, anyways—for the meaning they have to him. Traveling on the bus, he’ll sing hymns to himself—hymns that we sing on shows or that he’s recorded…

RG: He’s not a devout churchgoer, I wouldn’t say…

PR: But he’s a religious kind of man, I think. He feels a great contact with the Absolute…

(Play “House of Gold” (Side 2, Cut 2 of BM’s Decca lp DL-8769)

PR: He works on his farm which develops incredible strength…

RG: Yeah, we played the Black poodle in Nashville and we’d get through about 3:00 and he would go home’and sleep in the field for about an hour and then when dawn came up, he’d work all day till dark and then come and play the Poodle again—and this is the kind of schedule he kept.

db: And he’d still be in top form as a musician?

RG: Yeah—those were some of his best moments.

ANNCR: When we asked Bill about this grueling schedule and the kind of stamina it required, he simply shrugged it off.

BM: I don’t know, Doug…Back to the farming: you know, I was raised on a farm and I enjoy it so much. I like to do a lot of things on the farm that maybe down through the busy years of music why, I missed, you know. In the spring I farm and I raise cattle and hogs; and I have a pack of fox hounds that I enjoy going out a couple of nights a week if I’m around Nashville and listen to them run—I enjoy that kind of life. When I’m doing that, I just kind of use playing music on the side…(chuckles)…1 work, you know, and play music on the side…But I have always been a feller I guess could work 24 hours if I had to do it, you know, and stand up pretty good under it.

/This series continues next issue when the transcript of Program #2 will be resumed. Readers’ comments are invited; address them to: Doug Benson, Apt. 704, 45 Oakmount Road, Toronto 9,

Ontario, Canada. Any radio station wishing to inquire about dubbing these shows write to the same address^/

BILL MONROE : KING OF BLUE GRASS MUSIC: Part 4

Following is the fourth installment (continued from Vol. 2, No. 8) of a series of articles prepared by Doug Benson, drawn from material presented in the Radio McGill shows he produced, edited and announced in 1966-67. (Recurring abbreviations are: BM for Bill Monroe; PR for Peter Rowan; RG for Richard Greene; BGB for Blue Grass Boys; ANNCR for Announcer; db for Doug Benson.) Interviews conducted November 8-9, 1966 by db (with production and technical assistance from Richard Adams and a menacing array of ruthless engineers). Note: Although the words ascribed below to “db” and to “ANNCR” are spoken by the same voice on the finished tapes, it has been deemed necessary to differentiate between what was said during the give-and-take of the actual interviews (db) and what was said in retrospect at the later stage of piecing together the raw material (ANNCR)

PROGRAM #2 — BILL MONROE: THE MAN AND THE LEGEND (continued)

PR: And another thing, Doug, that is very important in Bill’s training as a musician was playing for square dances. Now there’s another example of—you establish a time for the dancers and then you play to the sound of their feet, just like with flamenco music—it’s done to the sound of the dancers’ feet. And I think that had an unquestionable effect on Bill’s playing. He’ll sometimes break into a fiddle rhythm on the mandolin—sort of a “Georgia shuffle” I guess you’d call it— and he says, “Now can’t you see the dancers?” or something like that … he’ll talk as if he was playing for a dance. He talks about fiddle tunes all having a “time” and the time is based on the dance. He’s played for the dancers and we haven’t played for the dancers, so we know nothing of what he’s talking about, except what comes out of him. And another time we were in New York driving down Fifth Avenue on a hay wagon for the New York Folk Festival and it was drawn by a horse and Bill was sitting in the back of the wagon and you could hear the horse’s hooves clomping along and he was playing “Grey Eagle” and he called my attention to the fact that he was playing in time with the horse’s hooves. So this re-occurs all through his music, you know, like playing to trains sounds….sounds ….

(Hit “Scotland” (Side 2, cut 3 of BM’s Decca lp DL-4601) hold for 60 seconds; then under)

db: Does he do anything like these exercises you mentioned to build up his own fingers or dexterity?

PR: He just goes and does nine or ten hours’ work on his farm—that does it.

RG: He’s not that kind of musician. That’s a discipline; that’s a whole other area of music… I think he said once that when he first started out he used to practise every day, but I’m sure it wasn’t scales and technique and stuff like that.

PR: No, but the practising every day had the same effect as practising every day.. ,as scales… You know, he just played all the time. That’s all you have to do really. Traveling on the road with Bill, playing every night in a town or in a club—you’re there all the time playing, and that’s the most important thing you can do to develop yourself as a musician, I think.

Richard Adams: I get the impression that in the eyes of most bluegrass people BM is a figure to be looked up to as nothing short of a god…

RG: That’s what he is. That’s the position he occupies in this field…

db: … the “Creator and Preserver” sort of thing, if you want to throw in theological terms.

RG: But besides that, he is possibly the finest musician, the man containing the most musician- ship… the highest level of skill in music—in the entire field. The singing…there’s no question about it at all. And instrumentally—to me there’s no question. I mean there are great musicians in the field, but not great the way he is. Earl Scruggs was a fantastic musician and innovator, but a lot of what he did depended upon what Bill did first. And he still does it today: every time we play, he’ll just play music that’s “up there.” It’s not just a matter of some mystical reverence—his actual deeds are more accomplished.

db: There is an aura of legend that surrounds him, but it’s completely justified, you see, by his phenomenal genius.

PR: His whole creed is not to let anything slip, not let anything fall…and while keeping his own music up there, to bring out the best in other musicians and to let them bring out the best in themselves.

ANNCR: Ralph Rinzler has written about “the manner in which Monroe actually breathes fire into the musicians who surround him.” Does he really function as a catalyst, urging his band members on through some intangible means?

PR: Yes, I’d say he does.

db: How? Can you express that kind of influence?

PR: Well, take any group of musicians and say they’re all competent musicians and put them with Bill and here’s this driving force through all the other music in the band, even if it’s only for one show. His time is solid and perfect and he holds himself responsible for the rest of the music, if it’s bluegrass. Everything seems to rest on his shoulders, the time and …

db: At his Roanoke festival, Carlton Haney is always talking about the “time” of bluegrass. What is this exactly?

PR: Well, that’s Bill’s strong offbeat keeping that time, but Carlton imbues “time” with mystical meaning, also …

RG: There are lots of mandolin players in the field and they all keep time but, you see, Bill keeps it in a way—I mean, this is just the offbeat on the mandolin; there are other things that time is composed of—but the offbeat on the mandolin, he does it so exactly right…I haven’t seen anyone on any instrument hit the offbeat as precisely as he does…It’s just so solid and perfect.

PR: Just chords…and of course the chords on that mandolin come out as a—I don’t know how to describe it except that instead of hearing a single note or hearing the single notes in a chord, the chord seems to some out as a cluster of notes all at once, strong and sharp.

ANNCR: BM is such a phenomenal mandolin virtuoso that you don’t ask if anyone is comparable to him as a performer on that instrument—you ask if anyone ever had a chance of coming close.

RG: There is one person who plays the mandolin who at one time could have.

db: Bobby Osborne?

RG: No, I’d say Frank Wakefield.

db: Tell us about that.

RG: Now he’s not deeply involved in music as he was before…a while ago. But he was after that style: He was after that picking style and the notes and everything…and he was like a child to Monroe—you know, his music—but it was the closest anyone came.

db: Was there a conscious attempt on his part?

RG: Yeah, he listened to the records, got every note, every little thing, and he went after playing that kind of style. But he’s let it slide; he hasn’t been playing the kind of music really where you can do that all the time.

db: Playing with a city-oriented group like the Greenbriar Boys would take the edge off that?

RG: Yeah, they don’t do Bill’s songs. You see, you have to have those songs and that time, those changes…

db: You have to play with BM.

RG: To play his style—his style is not only composed of what he does, but it’s composed of everything else, too: what he sings, what all the other instruments are doing…Now the Green- briar Boys don’t play strictly bluegrass, you know, they admit it. It’s not a sin; that’s just their choice.

db: How much longer do you think Bill will be an active performer?

PR: I think as long as he’s able.

RG: He keeps talking about ten years, which means…I mean, when anyone says they’re going to do something for ten years and they’ve already done it for over thirty, it means that there’s no point where he’s going to stop…I think as long as he’s alive—he’s the type of individual that is not going to decay by natural processes; he’s almost superhuman in a lot of ways, and I think as long as he breathes, he’ll be on top of the field. There won’t ever be a lapse. Like, well, you might say that Lester Flatt has gone down since some point. But Bill has always gone up and he’ll always go up until the end…

PR: Until he stops playing?

RG: Until he stops breathing. It’ll take some great physical catastrophe to stop him.

PR: Like getting old.

RG: No, I don’t think he’ll get old that way. I just can’t see it. He’s got too much fire in him…

PR: Well, it happens.

RG: Sure it happens. It happens to everybody else, but there are always examples of people who— I’ve seen it—some people have enough fire that they just don’t get old. Their hair gets grey, but they fight it and they stay on top. And I think he’s one of the few people I’ve met who is going to do that…and who is doing it: he’s already old in years, but certainly not in other ways.

db: It would certainly be hard to imagine the extent of inner conflict that he would face if he felt that he was losing something and yet a man like Monroe who, as you say, never wants to…

RG: He just wouldn’t allow it to happen. He just…

PR: That would be the tragedy of BM, if that happened.

RG: Yeah, because he wouldn’t allow it to happen and if it happened anyway, then…

PR: Well, one way or another I don’t think he’d let it happen. I think he’d stop before he hurt his own music.

db: He’s been heard to say that if any of these other guys get as good as him, he’ll quit. Now whether that’s facetious or just…

PR: I think he’ll eventually stop traveling on the road, and he’s talked about settling down to his place and teaching—actually teaching music—the way he does now, except instead of traveling …because the traveling is exhausting.

db: He would what—stay on the Opry and…?

PR: Yeah, maybe do that.

RG: The Opry will always be there.

ANNCR: From the Decca album “The High, Lonesome Sound of BM and his BGB”, here is one of the many songs based on Bill’s own life and experience—the 1952 recording of “Memories of Mother and Dad”, preceded and followed by comments from Pete and Richard.

PR: What would you call that dissonance that they’re singing there, because musically and poetically it’s a beautiful thing…

RG: That’s a sustained 7th.

PR: O.K.

(Play side 1, cut 3 of DL-4780) db: What comment would you make on that recording,”Memories of Mother and Dad”?

PR: Well, it’s a good example of one of Bill’s songs, because it relates to something from his own life, the death of his mother and father. The images in it are real images, like the tombstones and what’s carved on them…and it has religious overtones. And musically, it makes use of—what did you call it…distended 7th…perverted…?

ANNCR: So much for the technical explanation. If you were to ask Bill himself why he sang it like that, he would probably answer something to the effect that “We just had to do it that way to make it right.” He feels it should be done a certain way, so he does it a certain way. BM has a black-and-white approach to his music:some things belong in it and some things don’t. This attitude was manifested several times in our conversation. Bill would say things like: Being a BGB is like going to school—you have a good teacher over you who knows what you should do and what you shouldn’t do”…”The biggest job in bluegrass is keeping out what doesn’t belong in it” …or…”Take such-and-such a number—you know everything is in that number that should be in it.” Bill’s single-mindedness and deep conviction about what is right and what is wrong for his music is one of the factors that makes him great.

BM: That’s wonderful—for a musician to believe

in himself, if he really knows that what he’s doing is right. I have had some musicians with me that thought they was better than anybody that I’d ever had, you know—and they wasn’t—they was about a tenth-rater, and they never would make a man as good as Brad Keith or Rudy Lyle or Earl Scruggs. But they was fooled in their playing, you see. Now there’s some people that know when they can play and how good they are, and they don’t ever brag about it. And it’s good for a man to know how good he really is.

(Hit “Get Up John” (side 1, cut ^ of BM’s Decca lp DL-4601) hold, then under for ANNCR’s extro…end of Program #2)

In coming issues of BU, the transcript of Program #3—”The Relevance of Bluegrass Music to Urban Audiences”—will be printed. Readers’ comments on this series are invited. Please address them to: Bluegrass Breakdown Pub.;

Dug Denson, Editor; Apt. #3. 71 Keele St.,

Toronto 9, Ontario, Canada./