Home > Articles > The Archives > Tony Rice: A Distinct Talent

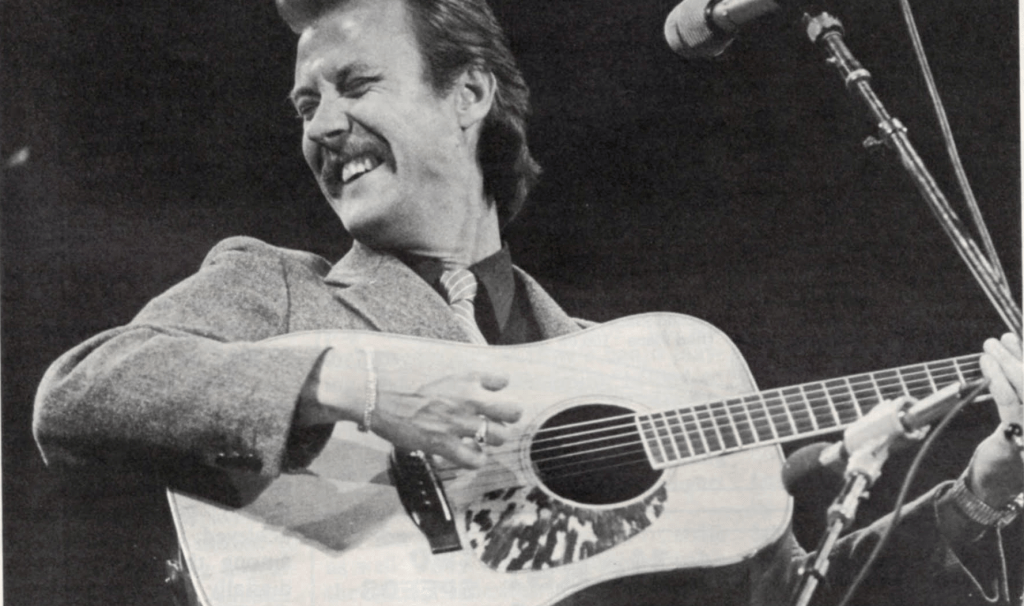

Tony Rice: A Distinct Talent

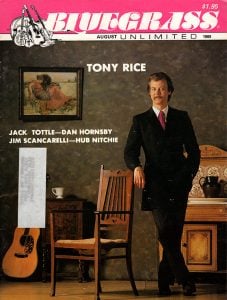

Reprinted from Bluegrass Unlimited Magazine

August 1989. Volume 24, Number 2

Perhaps no other single artist in this decade has had the impact on the broad genre of contemporary acoustic music than Tony Rice—the consummate folk musician whose stylistic command has gained him diverse groups of admirers as well as imitators all over the landscape. Afficionados of the acoustic jazz style which swept the world a few years back as Dawg Music, consider him an integral part of that music’s development. To bluegrass fans he represents the fresh, straight-ahead direction in the music so prevalent now among the third and fourth generation players.

But Rice himself seems to enjoy reaching fans in the in-between, who hang no pretense on his style; who, in his words, “like to listen and not categorize” his music.

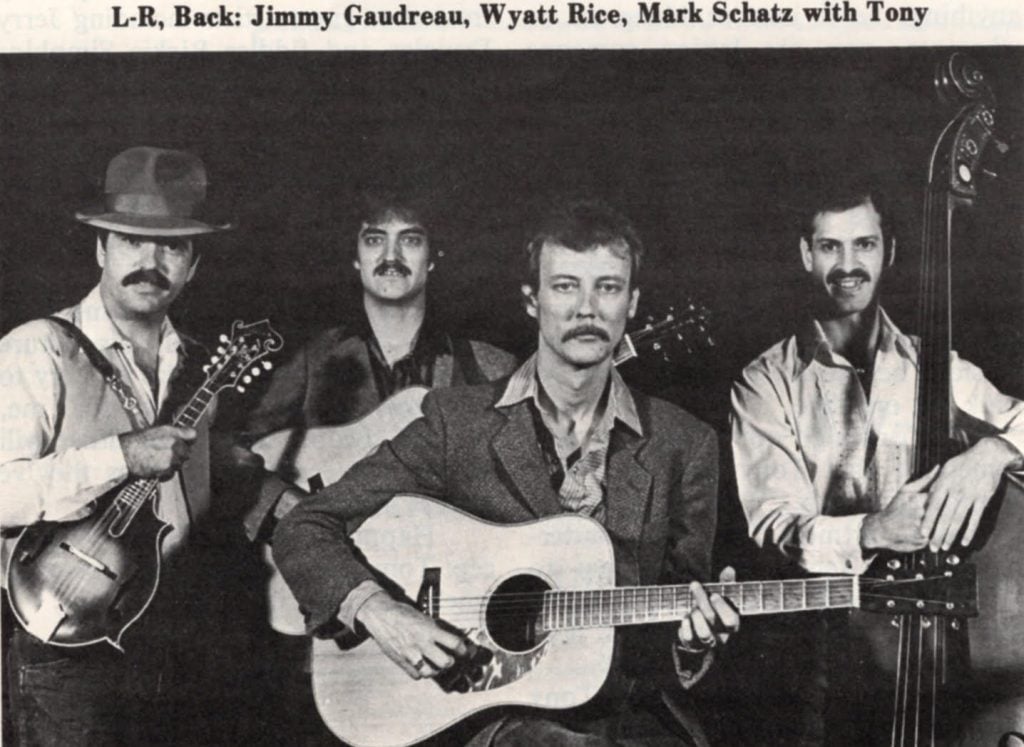

For the past three years he has toured and recorded with a trio of equally brilliant players who include mandolinist Jimmy Gaudreau, upright bassist Mark Schatz and Tony’s longtime protege and younger brother, Wyatt.

While his free wind style of flatpicking is the sauce of the music of the Tony Rice Unit, (it is, after all, his original claim to fame), Tony makes no bones about the fact that he is somewhat displaced. “I’m a bluegrass musician forever in my heart,” he proclaims. “But I want to explore and unearth some other things along the way.”

Tony feels the essence of his art is best expressed in a recording studio. He certainly has spent a lot of time there. By the end of 1988, he had no less than five recording projects at various stages of completion.

“I’m not much of a critic of my own work,” he offers, speaking from the comfortable living room of his home in Crystal River, Florida. From the hi-fi comes a track off “Native American,” his latest offering on the Rounder label. “But this record clicks pretty well, I think.”

There is a certain totality in Tony’s music these days. No longer is he just trying to bolster his 1970s reputation as the top-gun bluegrass flatpicker. Indeed, playing guitar doesn’t even have the priority it did just a few years ago. He admits his interest is more directed to the overall sound of his music.

“When I think that piano, drums and soprano saxophone are appropriate, I add them,” he says. “I really wanted to get out of restricting myself to one format. I still am very much a guitar player, but the challenge of the music lies elsewhere now.”

“Native American,” like its recent predecessors “Me And My Guitar” and “Cold On The Shoulder,” displays Tony’s long-held enthusiasm for the lyrical expressions from the folk, jazz, bluegrass and blues idioms. Admittedly, the content of those lyrics are an important concern of his, especially those which deal with reflective subjects. “I really don’t have much interest in your typical love songs where every line is a cliche,” he says. “I tend to pay more attention now to the songs as a whole rather than just the parts that I thought sounded good to me.”

Tony Rice the record producer is every bit as meticulous as Tony Rice the musician. He may spend months on a recording project (a rarity in the often no-frills business of acoustic music), insisting that perfection be achieved. This explains why he was among the first acoustic players to digitally record and mix an album for the CD market.

Born thirty-seven years ago in Danville, Virginia, Tony grew up in California. He is the second-oldest of four brothers, all of whom received musical encouragement from their dad Herb, who played mandolin and guitar in a number of bluegrass and country groups during the 1950s and 1960s.

Although southern California is not often considered fertile bluegrass ground, the Rice kids sought out the best pickers in the L.A. area to learn from. For oldest brother Larry, mandolinist Roland White was a major influence. For Tony, it was the brilliant, spirited flatpicking of Roland’s brother Clarence that fed him inspiration. Tony and Clarence first met as youngsters around 1963 in the studio of a local radio station. “It was the first time in my life I saw a Martin D-28,” recalls Tony with a smile. “And it’s the guitar I now own.

“At the time, the bluegrass and country scene in L.A. was really weird,” remembers Rice. “Bluegrass was just a novelty thing—there really weren’t that many good players around. But in the early ’60s, the folk revival had hit the colleges, and you had people like Ry Cooder, Herb Pederson and Chris Hillman hanging out, and all of a sudden I was surrounded by these guys that took an interest in this music my father showed me, and it was no longer a joke anymore.”

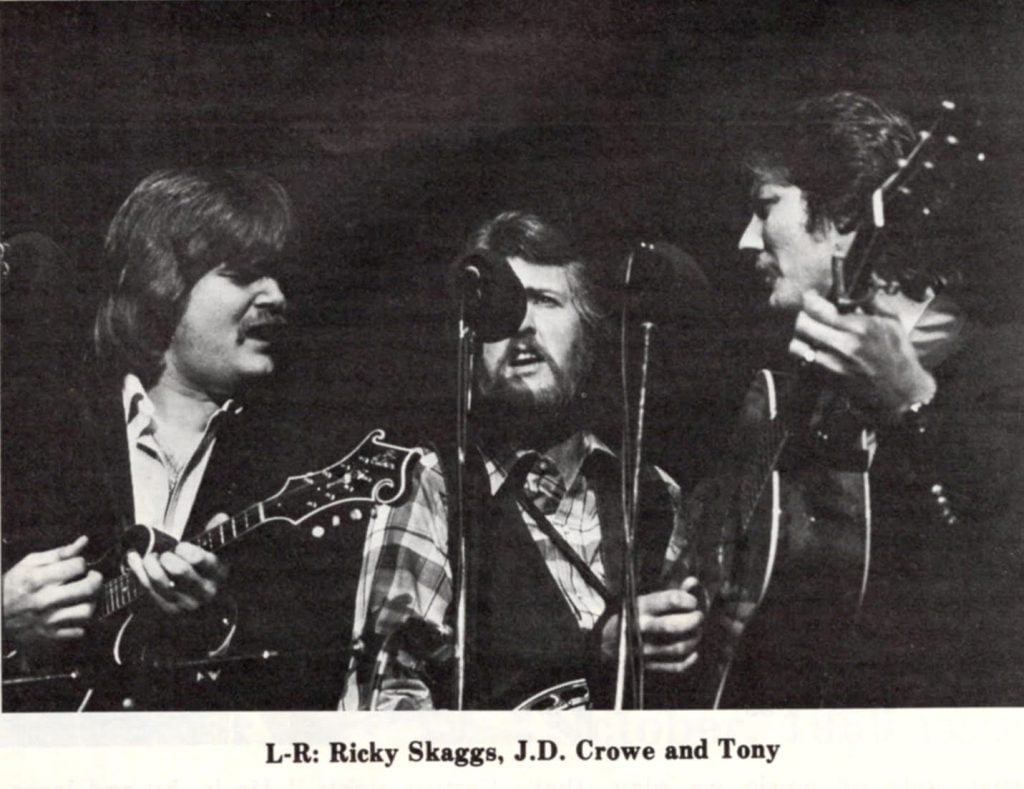

Tony took a lot of the L.A. influence with him when he moved to Kentucky in 1970. Following a yearlong stint with the Bluegrass Alliance, he joined his brother Larry in J.D. Crowe’s group, the New South.

The band had already established itself as one of the better and more progressive groups of its day, with its emphasis on contemporary material that was overlooked by many of the mainstream acts. Crowe’s banjo playing and impeccable timing helped to solidify Tony’s guitar playing. “It was a great vocal band, too,” says Rice, who was well on his way to becoming one of the more highly regarded singers in the field.

But there were moments of strife as well. Tony voiced his objections to the group’s desires to electronically amplify the proven acoustic format.

“I felt it was bogus,” he recalls. “I didn’t mind so much that we were plugging in and adding drums. But we were still doing the same material. I asked ‘Well, now that we’re louder, why are we still selling ourselves as a bluegrass band? Why are we still playing “No Mother Or Dad” this way?’ ”

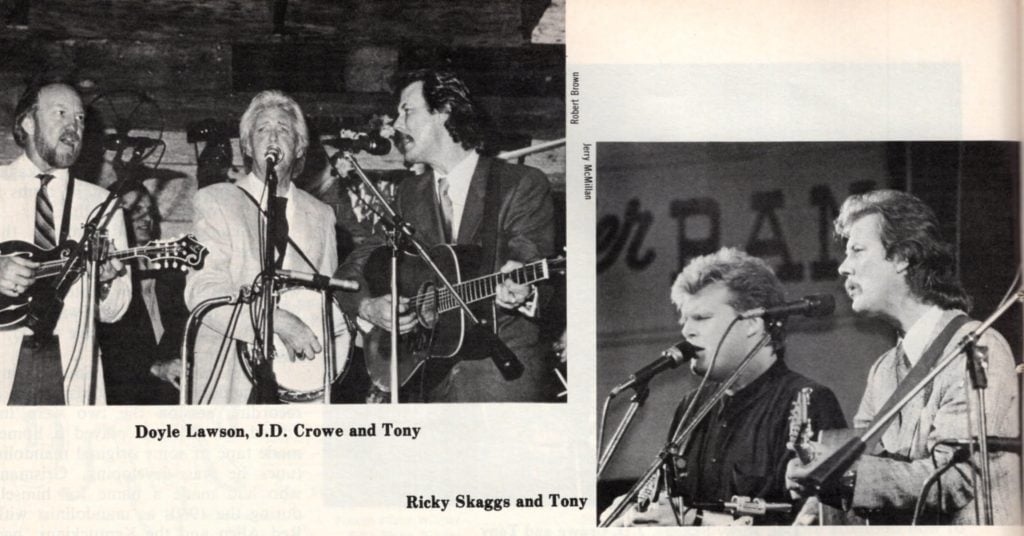

Larry Rice left the band in 1974 and was replaced by mandolinist Ricky Skaggs. According to Tony, Skaggs was responsible for what he terms a “rebirth” of the New South.

“Skaggs came in under the pretense that we return to the traditional-oriented sound. If we wanted to choose new material, that was O.K. just as long as it was in that context. It was an incredible sound, I thought.”

While with the New South, Tony met mandolinist David Grisman at a recording session the two were involved in. Grisman played a homemade tape of some original mandolin tunes he was developing. Grisman, who had made a name for himself during the 1960s as mandolinist with Red Allen and the Kentuckians, had combined a heretofore unheard of blend of disparate instrumental elements that included classical, jazz and bluegrass styles.

Although it was unlike anything he had heard before, Tony found the concept fascinating. In return, Grisman found Rice’s guitar skills to be extraordinary enough that he offered him a ground-floor opportunity to launch a new all-instrumental group. In early 1975 Tony served his notice with Crowe and departed once again for California.

The next four years was a “learning period” for Rice. “That stuff was pretty complex for someone who had been a three-chord bluegrass musician all his life. I began studying chord theory and I learned to read charts.” Rice developed his guitar playing skills, soaring far beyond the standards of the day with his fluid runs and melodic boldness. His reputation as superior flatpicker was cemented through his tenure with the David Grisman Quintet. However, his fine voice went unnoticed in the all-instrumental capacity of the David Grisman group, and in 1979 he decided that it was time to pursue some of his own ideas.

Tony’s first post-Grisman guitar album was the critically-acclaimed “Acoustics,” designed to connect the Grisman sound with Tony’s guitar- oriented views. The record was soon followed by the vocal-oriented “Man- zanita,” a collection of some of his favorite folk and bluegrass-oriented tunes.

But, by the release of his third Rounder guitar instrumental LP, it had become apparent to Tony that Dawg Music had lost a lot of its mystique with the public. “It wasn’t selling tickets or records,” he reflects with some animosity. “But it was weird in that those albums were the ones I put forth the most energy, the most intense work I ever did.”

However, interestingly enough, Rice was finding that, indeed, throughout the Grisman years he had not fallen out of favor with the longtime fans of his singing. Two important recording projects helped keep him in touch.

In 1980, a release of old-time country duets with former partner Ricky Skaggs reported sizzling sales figures (this in part because of Skaggs’ rise to country music prominence).

The following year, Rice was asked by Rounder to put together a bluegrass-oriented record—his first since 1975. He arranged a recording session with his former Kentucky bluegrass compatriots, J.D. Crowe and mandolinist Doyle Lawson. Ace fiddler Bobby Hicks was also invited, as was Tony’s long-time musical partner, upright bassist Todd Phillips. The resulting release was “The Bluegrass Album,” a collection of classic tunes, mainly from the ’40s and ’50s repertoire of Flatt and Scruggs and Bill Monroe. The record proved to be so popular that it has been followed up with three successive volumes, (two of which include the stunning Dobro work of Jerry Douglas), and a fifth is in the finishing stages.

“That material is so universal to all of us who have played bluegrass music,” says Rice. “I think that no matter where any of us ever go, or what style of music we play, that classic bluegrass from that period will remain in our souls forever.”

Rice explains his concurrent involvement with contemporary and traditional music styles reflects the ever-evaporating barriers between the two.

“Bluegrass is a term that means so much more now than it did twenty-five or thirty years ago,” stresses Rice, who has received his share of criticism from stalwarts of the traditional sound. “I mean, people would be surprised at what Bill Monroe would say, or not say, what bluegrass music really is. The beauty of any music form is that there are a lot of variations to be explored. As soon as you become a die-hard anything, be it jazz or bluegrass or whatever, you are letting someone make a puppet out of you, and you’re depriving yourself of a whole world of music.”

In 1985 Tony moved back East to begin putting together the Tony Rice Unit. “I wanted a band that was going to be more than just backup musicians,” says Tony. “These guys are integral to every aspect of the music. They amaze me every time we walk out on stage.”

Performing on stage is not something that Tony Rice is totally comfortable with. “I’m not a natural in that department,” he says, matter-of-factly. Often it comes down to “psyching myself into not being such a perfectionist with the music as it happens in that [live] environment.”

However, in recent times, Tony Rice the performer has become more outspoken in the area of what he calls “artists rights.” He is, by and large, not happy with “lack of common respect that some promoters—and they know who they are—have for the people who they hire to entertain their audiences.”

Specifically, Rice berates “basic human indignities” he often encounters at outdoor events. “I want to go out and play the best I can for the people who paid to see the show. It’s hard to do that when you have to use the restroom and there isn’t one near enough to go to and get back in time to go on.”

All of that not-withstanding, Tony enjoys the spontaneity of the concert situations. Patrons of the Tony Rice Unit performance are frequently treated to guest artists including Jerry Douglas and fiddler Rickie Simpkins who join the band from time to time, adding, says Rice “a different dimension” to the repertoire. [Editors note: According to Tony’s booking company, the Case Company, Rickie Simpkins has joined the band full-time as of July 1st.]

“I’ve got this music in me,” he says, when asked about his future plans. “I feel it. I visualize it. I try to somehow make it work—for me, anyway. People who listen either will accept it or reject it, just as they’ve always done.”

Happily, those listeners who accept Tony Rice’s music are in the overwhelming majority.

Share this article

1 Comment

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

How wonderful it is to hear my dad’s words from years ago, years after he’s gone. He loved Tony and he loved Bluegrass with a fiery ferver that is unmatched to this day in my eyes, even by professional musicians. I wish he were still here to see the incredible rise in the music he was so fond of.

-George Neill