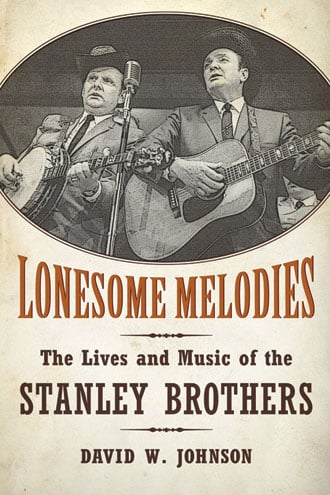

LONESOME MELODIES: THE LIVES AND MUSIC OF THE STANLEY BROTHERS

LONESOME MELODIES: THE LIVES AND MUSIC OF THE STANLEY BROTHERS—BY DAVID W. JOHNSON—University Press of Mississippi 9781617036460. Hardcover, 304 pp., b&w photos, notes, bibliography, discography, index, $50. (Univ. Press of Miss., 3825 Ridgewood Rd., Jackson, MS 39211, upress.state.ms.us.)

LONESOME MELODIES: THE LIVES AND MUSIC OF THE STANLEY BROTHERS—BY DAVID W. JOHNSON—University Press of Mississippi 9781617036460. Hardcover, 304 pp., b&w photos, notes, bibliography, discography, index, $50. (Univ. Press of Miss., 3825 Ridgewood Rd., Jackson, MS 39211, upress.state.ms.us.)

Much has been written over the past few years about the life of Ralph Stanley. John Wright got the ball rolling with his exemplary Traveling the High Way Home, and Ralph himself co-authored the fairly revealing Man Of Constant Sorrow with the help of Eddie Dean. Both touch on the life of Carter Stanley, but never before has a book delved into the history of the brothers together. Lonesome Melodies by David Johnson, which chronicles the lives and music of the Stanley Brothers, should be a welcome addition to the growing bluegrass canon. Unfortunately, it comes with some serious flaws.

Johnson begins with Ralph and Carter’s early years in the mountains of Southwest Virginia and continues chronologically on through Carter’s death in 1966 at the age of 41. He draws heavily on the two books about Ralph, but he also pulls from an interview Mike Seeger recorded with Carter and Ralph during their European tour in March 1966. This gives us a chance to hear Carter speak, even though he was already suffering from the disease (alcoholism) that would take his life in December. Johnson also interviewed Ralph, along with family members, friends, and musicians whose parts of the story haven’t been heard. He reveals that Carter had a daughter he never knew about, talks to Ralph’s first wife, Peggy, about her songwriting (“If That’s The Way You Feel”), and tells the story of Earl Scruggs objecting to Ralph’s playing “Cumberland Gap” on WCYB and the manager replying that Ralph would dedicate it to Earl on every show! So, in spite of my many frustrations, the book pulled me in and I found it hard to put down.

I have the biggest crow to pick with Johnson’s analysis of the Stanley’s recorded music. “Mother No Longer Awaits Me At Home” is not a reworking of Bill Monroe’s “Mother’s Only Sleeping.” (I checked.) Although the songs are superficially similar in theme and timing, the chords and the melodies are different. Likewise, “Our Darling’s Gone” does not have the same melody as “Can The Circle Be Unbroken.” His discussion of “Cry From The Cross”—a perfect opportunity to mention that this was the first time the Stanleys had used twin fiddle on record—is instead overburdened with editorializing about reverb. And his longing for a “more listenable version” made me wonder if he was unaware of the cut that Ralph made with Keith Whitley and Ricky Skaggs. Misfires of this magnitude weaken Johnson’s credibility as an authority.

Then there are the little things: Repetitions of whole paragraphs, attributing unsupported motives and feelings to Carter and Ralph, extraneous detail, and misspellings such as “Kline” in Curly Ray Cline. Stanley Brothers’ expert Gary Reid, whom I consulted, also caught many factual errors that I missed. What this book needed, more than anything, was a good editor. In spite of its flaws, Lonesome Melodies provides a useful, overarching view of the history of the Stanley Brothers. It is not, however, the last word. Read it, enjoy it, but keep your shaker of salt handy.MHH