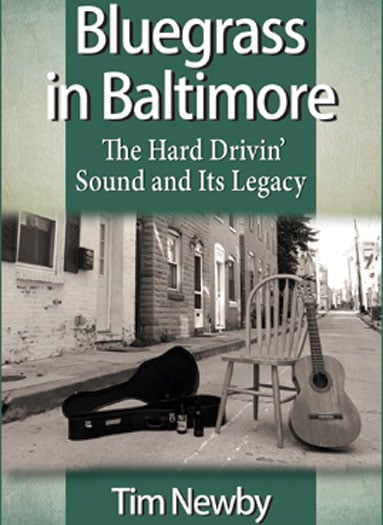

BLUEGRASS IN BALTIMORE: THE HARD DRIVIN’ SOUND AND ITS LEGACY

BLUEGRASS IN BALTIMORE: THE HARD DRIVIN’ SOUND AND ITS LEGACY

BLUEGRASS IN BALTIMORE: THE HARD DRIVIN’ SOUND AND ITS LEGACY

BY TIM NEWBY—McFarland 9780786494392. Softcover, b&w photos, 244 pp. (McFarland & Co., Inc., P.O. Box 611, Jefferson, NC 28640, www.mcfarlandbooks.com.)

Baltimore is not one of the first cities that comes to mind when you think about bluegrass. Yet, as Tim Newby’s Bluegrass in Baltimore reveals, the Maryland seaport was fertile ground for musicians in the ’50s and ’60s who were chomping at the bit to play the exciting new music that Bill Monroe and Flatt & Scruggs were pumping through the air. Hillbillies who had moved North to find work were desperate for the sounds of fiddles and banjos, and neighborhood bars provided a convenient setting for music fueled by alcohol and, yes, testosterone. For, with the exception of Hazel Dickens, if there were any women who braved the bar scene in Baltimore, they are not mentioned.

As the story unfolds, one realizes that there were actually two bluegrass scenes in Baltimore. There were the bars where the hard-driving Baltimore sound emerged in the capable hands of folks like Walter Hensley, Earl Taylor, Jim McCall, and “Boatwhistle” McIntyre. Other familiar names include Jack Cooke, Bob Baker, Del and Jerry McCoury, and Russ Hooper who was a source of much information for this book. Then there were the house parties, often at the home of Alyse Taubman and Willie Foshag, which brought into the mix city-folk like Mike Seeger and Tom Paley who would co-found the New Lost City Ramblers; Lamar Grier who would play banjo with Bill Monroe; and Alice Gerrard who would meet Hazel at one of these gatherings. Naturally, there was much intermingling between the two groups.

Country music parks also loomed large in the lives of Baltimore bluegrassers, for here they could see their heroes—Bill Monroe, Flatt & Scruggs, and the Stanley Brothers—perform in person. Newby’s discussion of Sunset Park in southeast Pennsylvania and New River Ranch in northern Maryland helps broaden the story. Ola Belle Reed and her brother Alex Campbell garner substantial attention here for their roles in both parks.

The last chapter examines the rise of Baltimore Blue Grass, Inc., the store which revitalized bluegrass in Baltimore and provided a day job for a young Mike Munford. Newby also notes the present-day success of the Charm City Folk and Bluegrass Festival.

Surprisingly, for a book this well-written, there are quite a few factual errors. Jim Brooks, not Ted Lundy, was the first banjo player with Alex and Ola Belle. Van, not Roni, is the youngest of the Stoneman children. And the first million seller in country music was “Wreck Of The Old 97”/“The Prisoner’s Song” by Vernon Dalhart, not Pop Stoneman’s “The Sinking Of The Titanic.” Still, Tim Newby has done a good job of documenting Baltimore’s rich bluegrass history. There is plenty of information here along with some highly entertaining stories. Recommended for sure.MHH