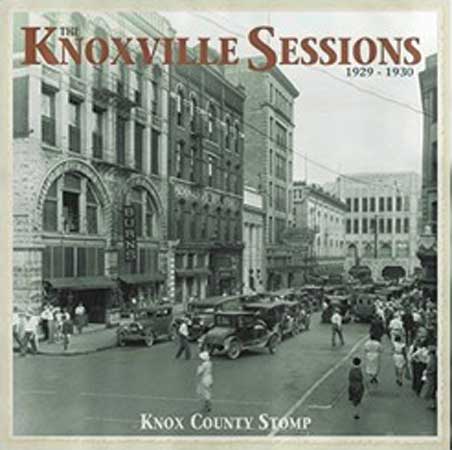

VARIOUS ARTISTS

VARIOUS ARTISTS

VARIOUS ARTISTS

THE KNOXVILLE SESSIONS, 1929-1930

Bear Family

BCD 16097

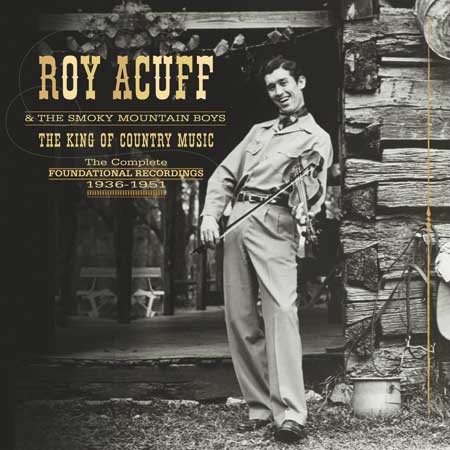

ROY ACUFF & THE SMOKY MOUNTAIN BOYS

ROY ACUFF & THE SMOKY MOUNTAIN BOYS

THE KING OF COUNTRY MUSIC: THE COMPLETE FOUNDATIONAL RECORDINGS, 1936-1951

Bear Family

BCD 17300

As the CD format sinks slowly into the west, Bear Family still maintains a high standard for comprehensive and well-documented country and bluegrass book/CD sets. Two current offerings combine thorough historical research with state-of-the-art sound preservation from period recordings. Both focus on music from Knoxville, Tenn., from the 1920s through the postwar era when local country music flourished on stations WNOX and WROL. After the war, bluegrass flourished there with artists such as Carl Story, Carl Butler, the Sauceman, Brewster, Webster, and Bailey Brothers groups, the Carlisles, Molly O’Day, and Jimmy Murphy. Earl Scruggs began his career in Knoxville with Lost John Miller’s band in 1945, returning to WROL with Lester Flatt & the Foggy Mountain Boys four years later.

Less remembered are records from two Knoxville recording trips by a team from the 1920s Brunswick label to capture regional talent for its Vocalion brand in 1929 and 1930. The visits were stimulated by local broadcasts and healthy hillbilly record sales at the Sterchi Brothers store on downtown Gay Street. Performers included the Tennessee Ramblers, Ridgel’s Fountain Citians, Southern Moonlight Entertainers, and Smoky Mountain Ramblers, names recalled today primarily by historians and record collectors. Unfortunately, their records went on sale just as the Stock Market took a dive in October 1929 and are now among the rarest of the era. Following considerable research, annotators Ted Olson and Tony Russell offer a wealth of personal and background detail about nearly everyone on the records, along with photos, documents, and brief biographies. The sound restoration is good, although several worn discs contain some of the set’s best performances.

Roy Acuff’s early career path and poor health paralleled Jimmie Rodgers. Each found himself playing music more by default than design. Tuberculosis took the Blue Yodeler from railroading to entertaining in 1925, and his blues-flavored blend of old and new songs made him a regional star until his death in 1933. Acuff’s dream of playing professional baseball was derailed when he failed to recover completely from severe sunstroke in 1929. After teaching himself to play fiddle during an extended convalescence, he joined a medicine show in 1932 with Clarence “Tom” Ashley, learning some good songs and developing his music and performance skills. Back in Knoxville that fall, Roy performed over WROL with his brother Spot and an energetic bass playing neighbor named Frank “Red” Jones. By then, slapped basses had replaced tubas in dance band rhythm sections, and Jones became the first to record with one in a southeastern string band. Basses emphasized the beat for jukebox dancers in bars and honky-tonks, and they became the norm in country string bands and Western Swing after the mid-1930s.

Roy Acuff’s Crazy Tennesseans band in 1936-’38 blended hymns, folk songs, frolics, and pop tunes into an eclectic mix that showed off various band members along with Roy himself. Their first hits included “New Greenback Dollar,” “Freight Train Blues,” “Great Speckled Bird” (no. 1 and 2), “Steel Guitar Chimes” and, of course, “Wabash Cannonball.” The last was sung by Sam “Dynamite” Hatcher on the record, but his accent was enough like Roy’s that no one detected the difference. The band consisted of Roy’s fiddle, Clell Summey’s resonator guitar, Jess Easterday’s guitar, Red Jones on string bass, and (in 1936 only) Hatcher’s mouth harp. Jones sang countrified versions of 1920s pop hits “Old Fashioned Love,” “Yes Sir, That’s My Baby,” and “Please Don’t Talk About Me When I’m Gone” in a cheerful upbeat style in contrast with Roy’s mournful mountain tenor. The band’s resonator guitar, fiddle, string bass, and vocal harmony was carving out a new, aggressive hot style, planting seeds for an evolving string band sound that would be called “bluegrass” in years to come.

Roy signed on in the fall of 1938, and soon Summey and Jones were replaced by Beecher Kirby (Bashful Brother Oswald) on resonator guitar and Lonnie (Pap) Wilson on bass. The Crazy Tennesseans became the Smoky Mountain Boys, and records, film, and The Opry soon made stars of them all. Roy’s impact rivaled Ernest Tubb, Red Foley, Eddy Arnold, and Bill Monroe, and he became as popular in the Southeast as Bob Wills was in the Southwest. More than anyone else, Roy Acuff represented country music from 1937 through the 1940s and created more than a few memorable performances along the way.

Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys (with another bass player) joined The Opry in 1939, adding another hot stringband with a high lead voice to the roster, and it wasn’t long before he and Roy had a serious falling out. After hearing Bill sing “Mule Skinner Blues,” Roy covered it on record in April 1940, months before Bill had an opportunity to cut it himself. Despite Roy’s apology, Bill wanted to beat him up and their musicians had to physically separate them. Later on though, the two became friends and their song lists rarely overlapped again. One reason was the introduction of song publishing to Nashville.

In the album notes, Gayle Dean Wardlow describes how Roy’s relationship with his label deteriorated over 1937-’38, when producer W.R. Calaway copyrighted “Great Speckle Bird” and other songs from the early sessions in his own name, so promised royalties failed to materialize. When an opportunity arose to gain control over his songs and become a publisher himself, Roy was more than ready. He had married Mildred Douglas in 1936 and, when he persuaded composer Fred Rose to form a publishing house, Mildred took the opportunity to develop her business skills as a semi-silent partner. Acuff-Rose opened in 1942 and new songs quickly started earning money for country composers including, of course, Rose himself. Wartime hits generated unprecedented revenues and encouraged other talented writers such as Arthur Q. Smith, Jim Anglin, Jenny Lou Carson, Walter Bailes, and Hank Williams to place original songs with Acuff-Rose and other publishers. A growing catalog let Roy choose what he wanted to record, including songs prepared and arranged for him by Rose himself along with songs he purchased outright.

In the record notes, Colin Escott describes the situation as a mixed blessing: “Some of Rose’s songs—“Prodigal Son,” “Blue Eyes Crying In The Rain,” and “We Live In Two Different Worlds”—ideally suited Acuff. Others were closer to the pop confections with which Rose had made his name and didn’t play to Acuff’s ‘full-throated, unabashed’ mountain singing.” True enough, but Rose also contributed “Low And Lonely,” “Be Honest With Me,” “Fireball Mail,” “Waltz Of The Wind,” and “Pins And Needles” to an impressive list of Acuff hits.

Meanwhile, younger artists such as Bill Monroe and the Stanley Brothers were combining new styles of solo and harmony singing with an updated unplugged sound that drew energy from Earl Scruggs’ fire-breathing five-string banjo techniques. Roy countered by ditching the accordion, hiring the great Joe Zinkan on bass, reclaiming Oswald’s resonator guitar, and relinquishing the fiddling to great stylists such as Tommy Magness, Benny Martin, or Howdy Forrester. This collection ends with Roy’s last Columbia records from 1951, where Martin is heard to advantage, playing fiddle, guitar, banjo and mandolin at various times, and Zinkan plays superb rhythm guitar. Among several good songs is a menacing Cold War admonition, “Advice To Joe [Stalin],” sung by a trio with Martin and Zinkan on two guitars. Resonator guitar pioneer Speedy Krise wrote “A Plastic Heart,” accurately predicting heart transplant surgery more than 15 years later. A goofy Louvin Brothers song, “Bald Knob, Arkansas” (recently revived by Leroy Troy), features Martin on both mandolin and banjo. By year’s end, his 15-year association with Columbia Records concluded, just as Howdy Forrester took Benny Martin’s place with the Smoky Mountain Boys, and Benny joined Lester Flatt & Earl Scruggs.

This comprehensive collection includes all Acuff titles from 1936 through 1951, with surviving outtakes, extensive notes by Gayle Dean Wardlow and Colin Escott, and DVD selections from the movie Grand Ole Opry (1940), with Roy Acuff, Uncle Dave Macon, and the Weaver Brothers and Elviry. If you’re curious about the roots of bluegrass, listening to Roy Acuff’s music will enlighten you and pleasantly surprise you, too.(www.bear-family.com)RKS